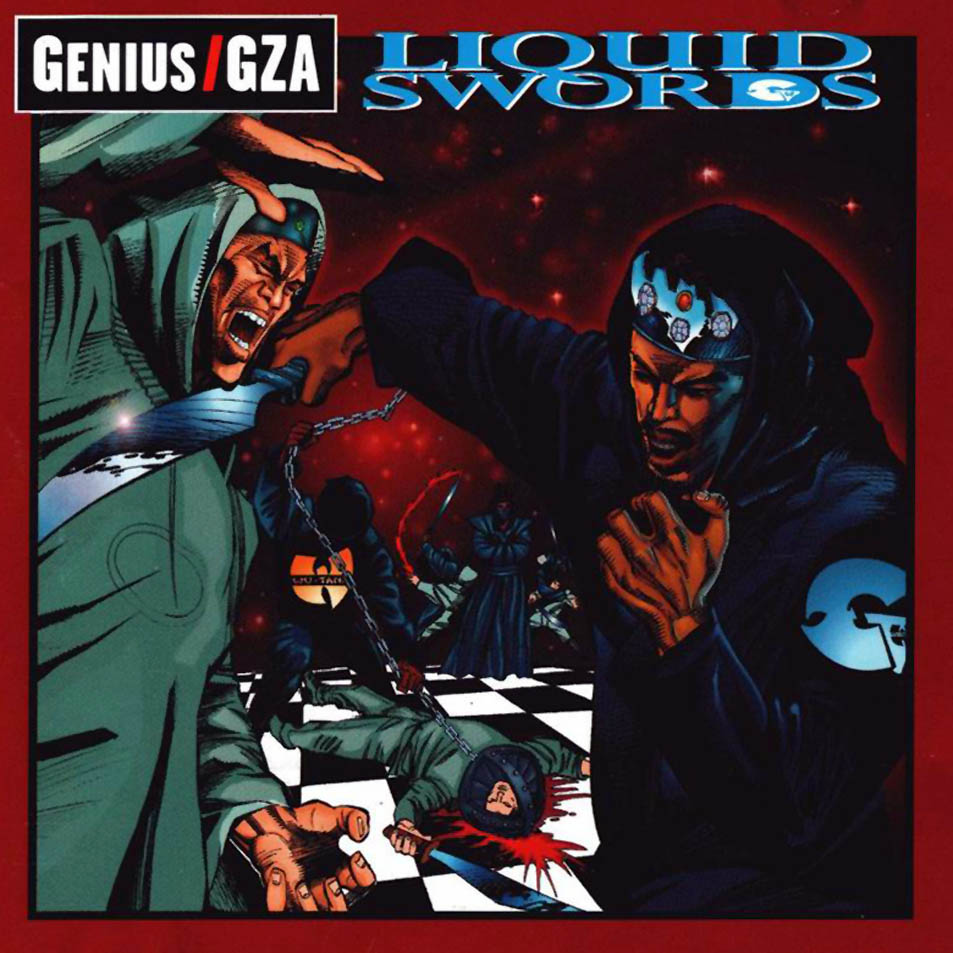

Lone Wolf And Cub is a series of fantastically bloody and grimy Japanese samurai movies from the '70s, and the whole saga opens with the sort of scene that sticks in your soul forever once you've seen it. A samurai warrior knees on the floor of his destroyed home, speaking gravely to his infant son. The samurai's wife has been killed, and the treacherous shogun has sent ninjas to hunt him. He knows there is so much death ahead of him. He puts his sword on one side and a ball on the other, and he tells his uncomprehending son to pick one, the sword or the ball. If he chooses the ball, the samurai will send the kid to be with his mother. If he chooses the sword, then he will join his father, and they will live together as monsters, demons, killing to live. The baby crawls to the sword, and his father tells him that he should've chosen the ball. In 1980, an American distributor stitched the first two Lone Wolf And Cub movies together crudely, giving them an English-translation dub and a haunting synth score. And even in that chopped-all-to-shit form, the resulting movie, Shogun Assassin, still has a power and a gravity to it. Through the movie, we see the samurai stalking off into battle, murdering countless foes, leaving blood geysering. There's no joy or satisfaction or vengeance in what he's doing. He's grim and dutiful and solitary. He carries himself with regret but accepts his role in the universe. 20 years ago, GZA released Liquid Swords, a rap album of uncommon grace and focus. (Its actual anniversary is Saturday.) He opened it with that sword-or-ball monologue, and samples from Shogun Assassin play throughout. And on that album, GZA plays a similar role to that bitter, death-haunted samurai. He's hard and insular and still and thoughtful and dangerous, a mysterious figure stalking the plains. And in 1995, you could be all those things and still be a rap star. That had never happened before, and it hasn't happened since.

GZA was such a meditative and lonely and quiet figure that it's amazing he worked as well as he did within the chaotic group dynamics of the Wu-Tang Clan, arguably the greatest crew in rap history. But GZA's role within the group was a fascinating one. He was the oldest member of the group -- 29 when he released Liquid Swords -- and the most experienced. He'd established himself as a rapper long before the RZA, his younger cousin, had come up with the whole Wu-Tang concept. He was a battle-rap star; there are legendary stories about the time he took on a very young Jay-Z at a Muslim community center in Brooklyn. And he'd already had his stories of music-industry heartbreak, having seen Cold Chillin' Records allow his 1991 album Words From The Genius to fizzle. To hear them tell it, the other members of the group regarded the GZA with awe and reverence. They were, after all, kids -- most of them 19 or 20, guys with neighborhood reputations as great rappers but guys who were new to the idea of a music industry. And here was a guy who'd been there and done things. On Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), GZA had that line about how your A&R was a mountain climber who plays the electric guitar; odds are good that some of the other guys in the group were just learning what an A&R even was. And he rapped with a cold, clinical, unshowy insistence. The other rappers in the group were these loud and outsized personalities. GZA lurked in the back, grizzled and sage where everyone else was young and flamboyant and hungry.

When they talk about what GZA brought to the table, the other members of Wu-Tang, as well as a lot of fans, talk about things like mathematics or conceptual rigor. For me, though, the only aspects of Liquid Swords that have aged badly are the ones where he tries to get too witty or playful with his words -- finding punny ways to clown various record companies on "Labels," working a goofy acronym into the title and central hook of "B.I.B.L.E. (Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth)." For me, GZA's best lyrical moments on the album come from isolated bursts of imagery: "Blood splashed, rushing fast like running rivers," "turn off the lights, light a candle, have a seance." And there is great strength in his stillness, in the way his raspy calm never breaks even when he's talking about desperate circumstances. On the hook of the title track, GZA brought back a routine -- "When the MCs came to live out the name..." -- that he used on the battle circuit in the mid-'80s. But even though that's, more or less, a "yes yes y'all" chant, he delivers it with an undemonstrative flatness, like he's simply stating facts.

RZA, on an incredible and maybe-never-equaled hot streak in 1995, produced all of Liquid Swords, and he intuitively understood GZA's whole aesthetic. Liquid Swords is the closest thing to goth that RZA ever produced. It's dark and meditative. Even as he samples old soul records and Three Dog Night, RZA only allows brief shards of melody to come through, and they sound like candle flickers in a dark room with painted-black walls. Whenever we hear the sustained analog-keyboard ring of the Shogun Assassin score, it seems to lead seamlessly into whatever the next beat was. Every sound is tense and dark and smothered. Every member of the Wu-Tang Clan raps on Liquid Swords, but all of them reel themselves in, nobody doing anything outrageous enough to interrupt the mood. Even when Ghostface Killah comes through with a flamboyantly surreal flex -- "Ironman be sipping rum out of Stanley Cups" -- he's there to serve as a contrast, as a supporting character. GZA wasn't a natural leading man, but he still set the tone throughout.

Of course, rap history is built on leading men. Style, personality, electric presence -- virtually every rap star in history has all these things in off-the-charts amounts. GZA wasn't about any of those things, and for a quick moment, that didn't matter. The Wu-Tang Clan had come through and sucked so much of rap into their orbit that they could get away with things. They'd captured the imaginations of hordes of suburban kids like me, and they probably could've put their logo on toothpaste and sold it to us. RZA knew what he was doing when he got the group's two most outsized personalities, Method Man and Ol' Dirty Bastard, to release the first two solo albums. And by the time GZA's turn came around, they were such a hot property that a craggy, insular Man With No Name character like GZA could come through and sell records. It wouldn't last. This was a brief historical anomaly. Other rappers talk about Liquid Swords with deep admiration, as they should. And GZA's deep sense of calm certainly had an effect on the backpack underground that would begin to blossom around New York a few years later. But Liquid Swords is not an album that had a deep effect on rap at every level. Another rap album that came out the very same day would become a way more influential force. (More on that tomorrow.) But I don't know that I'd call it an influential album. Instead, Liquid Swords was something else. It was a moment captured vividly, a sound laid down just about as well as that sound could possibly be done. There are very few rap albums -- or albums in any genre -- that evoke a specific mood the way Liquid Swords did. It struck deep chords, and those chords resonate still.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]