I. EAUX CLAIRES

In what seems like a quiet hour, loose activity fills the lives of the National's five members. It's that period of time before the band takes the stage; last-minute decisions and logistics are being hammered out, but it's also kind of boring and filled with a lot of pacing around and small talk. Frontman Matt Berninger is supposed to write the lyrics to "Sorrow" on a skateboard for the Tony Hawk Foundation's Boards + Bands Auction and, despite having once performed the song for six hours straight, he can't quite remember the next line. Drummer Bryan Devendorf, seated nearby in-between smoke breaks -- American Spirits, the yellow pack -- tries to help him out. Guitarist Aaron Dessner is working on tonight's setlist. His brother, Bryce (also guitar), mills around outside, hanging with Sufjan Stevens, then Justin Vernon, then Spoon frontman Britt Daniel. Bassist Scott Devendorf has to choose their walk-on song; he's feeling something by the Doors, but it's too sunny for their usual "Riders On The Storm" so he goes with "L.A. Woman."

At some point, Berninger's father enters with another autograph-related task for the singer. I hand him my notebook and he bends his head as his father dictates a name to him. Berninger's hair -- which he wears long now, in blatant but somehow successful defiance of a receding hairline -- hangs down over his eyes while he writes.

"Katie from Nebraska, drove all the way, all night, to get here to see the National," Berninger's father explains. And then, by way of further explanation, turns to me and says, "I still have to drum up fans."

"Your job's not done yet?" I ask. "I think they're all right now."

"Do you have any kids?"

"I do not."

"Well, you'll find out someday."

"He still goes around with loudspeakers on the car," Berninger jokes about his father. "CHECK OUT THE NATIONAL! CINCINNATI, OHIO." Later, Berninger's dad tells me that Katie From Nebraska is actually 16 years old; her own father had driven her so she could see the National for the first time.

This all takes place backstage on the first night of the inaugural year of Eaux Claires, a new festival in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, a dream project of Justin Vernon (who wrote the first Bon Iver album in a cabin not far from the festival grounds), on which he partnered with Aaron to bring to life. I watch everything happen while seated on a small bench in a white room with pristine air-conditioning that feels like a medicinal refuge compared to the suffocatingly hot July day outside these walls. Sufjan Stevens hangs around, deliberating what he's going to sing with the National tonight. "Yeah, I could do 'Terrible Love,' and 'Vanderlyle' ... I might be so drunk by the end ..." he trails off.

"If you feel like playing, play," Aaron replies in the level way in which the Dessner twins say just about everything.

Stevens decides on those, as well as "I Need My Girl" and "Afraid Of Everyone," before kinda giving Aaron shit about the clothes he has on -- "Is that what you're wearing onstage?"

The whole night is a rare moment for the National in 2015. They live in different places, lead different lives. The engine is just starting up for the band's next phase. But, in the meantime, 2015 is a year of the band's life defined by other aspects of their existence, of the other concerns and collaborations and projects that they disperse and pursue. New festivals, new bands, new compilations -- the kind of stuff where they can explore different sounds and ideas, work with other people. This is a chapter where they can take a pause from the machinery of the National, and a process through which something new might come back into the band's own DNA when they find their way back to each other. While their seventh album is still in its early gestation period, that chapter of diversions will be coming to a close in 2015. The National may have come off as relatively silent in recent times, but each component of the group has been whirring down different avenues, pushing outward or to one side or the other -- each of these five men tracing a convoluted path back to when they're all standing on stage together again.

Over the course of several months following Eaux Claires, I meet with various members of the National around New York. What follows are glimpses of what they've been up to, and where they're going -- snapshots of the band in transition.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=KehwyWmXr3U[/videoembed]

II. HALF AWAKE IN A FAKE EMPIRE

The National are at an odd point as a band: After coming off as underdogs for years, they are now firmly the establishment. And the transition can feel, in the moment, sudden. The career of the National has been one of those paradoxes; it feels like they've perpetually been having their breakthrough for a whole decade. It's hard to remember when the National weren't one of the foremost names in the indie rock, but at the same time, each new album since 2005's Alligator could have been greeted with some version of "Ah, now they've finally made it." Their path to indie-rock royalty was incremental. Alligator was one of those great albums you missed if you weren't paying attention; it was also where the identity of the band truly cohered for the first time and the moment when they truly made a mark on the music landscape. Caught in the heat of the mid-'00s blog-rock moment, it was also the phase in the band's life that yielded the legendary tale of a headlining tour where Clap Your Hands Say Yeah! opened; the venues were packed, but large swathes of the crowd departed before the National even took the stage.

The album's successor, Boxer, was the slowest-burner in a discography of slow-burners, where another facet of their identity -- the tense exactness of their arrangements, the "stateliness" -- came together. Its opener, "Fake Empire," was used in the Obama campaign, which would seem to have been about as significant an achievement as one could have asked for this band. Boxer's exposure felt like a delayed release -- the band's stature swelled over time during that album cycle, and burst only upon the release of High Violet in 2010. At the time, that felt like a logical conclusion to it all -- the commercial success of hitting #3 on the US Billboard 200, finally the wider critical attention, and the establishment of the National's 21st century brand of arena-ready anthems. But in 2013, Trouble Will Find Me seemed to actually complete the arc. The day it was released, the band played three surprise gigs in New York locations that traced their history. They began at lunchtime at Sycamore, a bar in Ditmas Park, a neighborhood closely tied to the band. Next was Public Assembly in Williamsburg, a neighborhood that was crucial to the New York music scene during the band's formative years, and was the site of their practice space in the early '00s. It ended at Mercury Lounge, where Berninger had seen the Strokes and thought: Here it is -- this is a New York band and a New York venue. The National had played there several times themselves, but never to much of a crowd; that night; thousands more would've crammed into the 250-capacity venue if they could have. It felt like a climactic day in of itself, but only weeks later, they headlined Barclays Center, the new-ish arena in the center of Brooklyn. The coronation had been complete, after a process that went, applicably, like the finest of the National's music: subtly building and building and building until, finally, the release.

By then, they were inarguably at the center of their corner of the universe. They had risen to the top of the "indie" heap; they had become, in fact, the closest thing we had to "rockstars" in this decade. Alongside their friends St. Vincent and Arcade Fire, the National were the sort of act that ruled over one world and, as such, were the face of indie rock to everything outside of it; in late 2013, the National contributed "Lean" to the Hunger Games: Catching Fire soundtrack. They'd arrived. A few times over now. But now they'd really arrived, no longer the group your friends in art class thought of as the greatest thing going, but the group everyone's parents knew, too, and the group that old high school friends you didn't remember as the types to particularly follow the ins and outs of contemporary rock music would quote in their Facebook statuses. The group that Katie From Nebraska drives all the way to see. Even if you were watching back in 2005 or 2007 and arguing for the larger stage this band seemed to deserve, seemed to need, it was still a surreal vision, to witness them having actually reached this point.

Two questions come out of that. The first one is some mixture of "Why?" and "How?" It's not a very legible career arc in any other instance: a band formed when everyone was already in their mid- or late-20s, holding down jobs; two albums of searching for what made them tick, of them trying to figure out how to be a band together, but doing so publicly; the beginning of success as they turned the corner into their 30s; and then, as 40 closed in, rising to a level of success that none of them expected. The band members themselves have fairly practical explanations for it. Bryce feels the songs, emphatically worked over and over, earn staying power. The flipside of that is that these aren't songs that, as Scott puts it, hit you over the head. "If you sit with it for a while, it gets to you," he muses. It used to bum out Berninger when people called the National "a grower"; it made him feel like that meant it "took work" to like them. But then he considered the time it took them to be satisfied with a song of their own. "I guess that's sort of just the nature of the songs we write," he offers. "They're kind of designed to reveal themselves slowly, because they reveal themselves slowly to us while we're writing them."

But even if you believe in what you're creating, the transition made by the National is still unique enough that the band members haven't entirely worked their heads around it. "It was interesting to realize -- and, exhilarating to realize -- that we could do it, and that we had grown, that we had this group of people that worked together with us, helping to create something that does work in those spaces," Aaron says of their graduation to an arena stage. "But...if you had said that in 1999 or 2003 or even in 2007, I would have been like, 'Hmm, I don't know.'" Berninger remembers a turning point when the band went to the Grammys for Trouble Will Find Me. "It was this bizarre thing, to be there and be like, 'Do we have the same job as Pink?'" He recalls. "I was thinking, 'These are my colleagues? This is the business I'm in? I have the same job, I just do it differently?'"

Whether it's onstage at Barclays or, more likely, headlining a festival, the National have crafted an arena rock for our era. They're the closest we have to a Bruce Springsteen for our generation, for kids maybe raised in the suburbs, but pulled back and forth between there and the city, always tempted with some vague promise of something else in some other place but never knowing if the search could really be fruitful. For whom the lines "Tired and wired/We ruin too easy" are more legible than "'Cause tramps like us/Baby, we were born to run." This is speaking to a particular slice of America -- middle-class, perhaps Middle American but seeking urban enclaves on either coast -- and for that slice of America, there hasn't been a voice more definitive than the National.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=S97xQKZDV_4[/videoembed]

It's their whole sound, their whole ethos. The tightly wound tension of Boxer is the aural equivalent of what it felt like to breathe in the air of a post-9/11, post-Recession America. There's a sense of dejected paralysis, a feeling of "Is that all there is?" -- filling music for a generation raised in one version of America and inheriting another. And when they broke out of that sound into the wider expanses of High Violet and Trouble Will Find Me, it was the feeling of something having to break, of beleaguered anthems written for depleted times. Songs like "Bloodbuzz Ohio" or "Terrible Love" or "Sea Of Love" can fill large spaces, but they fill them with a language that's more widely spoken today. It's not a triumphant key change for the last chorus. It's a little gray, a little contemplative, even in its catharsis. It's music that surveys the landscape, measures it, and is trying to tear something open within it. The fact that the National don't know what that "something" is any more than we in the audience do is part of the point. The biggest moments in National music are still shot through with small, interior things, with doubt and desperation. It gestures toward maximalism with restrained movements, a soundtrack for a confusing century.

If you look back at the National's modest beginnings, back to 2001's self-titled debut, there isn't even a hint of this. It's not as if they were setting out to be a band that gave voice to some generational ennui or frustration. But a lot of times, the bands most adept at doing that aren't looking for it. It finds them. Even if the band did offer up State Of The Nation observations like "We're half awake/ in a fake empire," it was conveyed with Berninger's abstract and personal lyrics. It just so happened that his visions, and the intricate storm the band built with them, captured something that was very real, something that made this band matter in ways nobody could have seen in their earliest days.

The second question: Well, then, what do you do next?

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=yfySK7CLEEg[/videoembed]

III. OTHER LIVES

The answer, in the near term, was: "Not another National record." While the band were prolific enough during the Trouble Will Find Me sessions that they initially implied they wanted to release a follow-up quickly, they backed away from that idea in favor of actually taking a significant break from the National, something they hadn't afforded themselves in years. Side projects and outside collaborations have been a part of the National for most of their existence, but this would be a time for everyone to explore other things, sometimes apart or sometimes together, and come back to the National with something different, when it was time.

While Berninger's guested on plenty of other people's songs and worked with his bandmates in other capacities, he never had his own separate collaboration with a full album. That is, until he and Brent Knopf (Menomena, Ramona Falls) brought EL VY to the world this year. The two met years ago while touring together, and the idea of EL VY has been around a while, too, with Berninger estimating that they began talking about it six years ago. Berninger told Knopf that he should send him some sketches to check out; Knopf responded with a folder of more than 300 little ideas, at varying levels of completion. Then all through the time that the National were recording and touring High Violet and Trouble Will Find Me, Berninger would work his way into the material, coming up with words and melodies and trading them back and forth with Knopf. When the National decided to take more of a break after Trouble Will Find Me, he and Knopf were finally able to finish the album, Return To The Moon. They picked a name, EL VY, even though Berninger stresses neither of them wanted to think of it as a band, neither of them wanted to be in another band. "[EL VY] comes from the fact that every other band name was taken in the universe. That was the last one," Berninger deadpans. In reality, the fact that it looked like two sets of initials made it work.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=TYr2FWnSaAo[/videoembed]

Neither he nor Knopf totally knows what the future of EL VY will be beyond the album and this year's tour dates. Berninger would love to do it again, but with the same "whenever it happens, it happens" approach. "Up until a few months ago, we weren't even sure if we were going to do it," he explains. "It didn't have to come out. Neither of us needed it. The one rule was never let any of this cause any anxiety." It's a rule that has been applied in the lives of the National in general. By any of their estimations, it used to be a pretty painful experience to finish a National record. But they learned to enjoy the life they'd built over time, and learned that other projects like EL VY were a way to keep the relationships working, to give them room to breathe. "I think it's one of the reasons why we're still together," he offers.

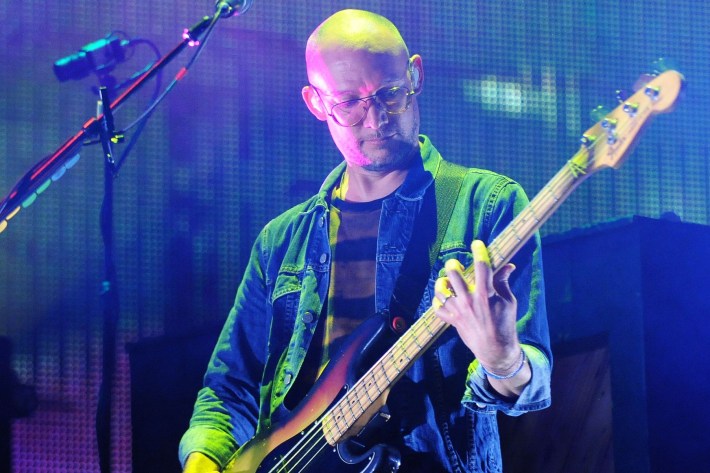

Meanwhile, the Devendorf brothers have been exploring other projects as well, forming an experimental group called Lanzendorf with Benjamin Lanz, a multi-instrumentalist who's toured with Beirut and the National. Lanz is mostly a trombonist with the latter but plays guitar in Lanzendorf, while Scott and Bryan stick to their usual instruments. The project began spontaneously at a show where the National needed an opener, so they became one; the project's identity followed suit, with the group only having played a few shows and always performing in a long-form, improvised jam that hews closer to krautrock and space-rock than anything in the National's discography.

"There's not much intention there," Bryan says of Lanzendorf. "It just ends up becoming whatever it is." That's been the case over the course of the gigs -- no two of which have been very similar to each other -- but now they've also recorded an album. Bryan describes their recording process as being: Fixate on one idea for 20 minutes or so; sift through it and find the song afterward. The resulting album took on a little more structure than their free-form live shows. It's split into eight songs, and it has vocal parts, some of which were done by Scott and Lanz, some of which were by Bryce's girlfriend, a singer from France.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=YST01938j4s[/videoembed]

In general, Bryan's side projects happen without much of a plan, rooted more in curiosity or random exploration. Working in a home studio he's putting together in his house in Cincinnati, he's been revisiting solo material dubbed Shit Attack. The most interesting stuff, by his estimation, is 13 or 14 years old. There's a cover of Fleetwood Mac's "Dreams." He plays just about everything, aside from a guitar part from Aaron on one song; he sings, too, borrowing unused lyrics from Berninger. ("Unauthorized -- the cease-and-desist is in the mail," Berninger quips when he overhears us discussing it.) "It's messy," Bryan says, describing Shit Attack. "It's charming in that way." The project may never see an official release, but he also has Pfarmers, a group that features Danny Seim from Menomena, and trombonist Dave Nelson, who's toured with the National as well. While he asserts that Seim does "most of the heavy lifting" in actually putting Pfarmers' material together, it's also been a place for Bryan to try out ideas that don't really fit into the framework of the National's music -- namely, wonky synth-based sonics with his drums that can hint at industrial. As it goes with Bryan's other projects, Pfarmers is a casual, laid-back thing without much of a plan; even so, they have a follow-up to this year's debut already finished and slated for release next year.

Leading somewhat of a musical double life, Bryce's outside collaborations date back the earliest of any member of the band, and in ways are more extensive and removed than those of the other members. The man is involved in a dizzying array of projects. Alejandro González Iñárritu's new film, The Revenant, features a score composed by Bryce with Ryuchi Sakamoto and Alva Noto. In the last few years, he's put out classical work -- St. Carolyn By The Sea, which was released as a split with Johnny Greenwood's There Will Be Blood Suite, and Aheym, performed by Kronos Quartet -- and the list of performances of his commissioned work has expanded from the L.A. and New York Philharmonics to new ventures during his time in Europe. Next year, the New York City Ballet's Justin Peck will debut a new narrative work, featuring a commissioned score from Bryce. He's curating a new festival in Cork, after being approached by Mary Hickson, who used to run the Opera House there, and actor Cillian Murphy. That's before you get to the stuff that mixes elements of his worlds together. MusicNOW, the festival he founded in Cincinnati and often features a mixture of contemporary classical with indie rock and visual art, celebrated its tenth year in March. Bryce hopes to release an album version of Planetarium, a song cycle he collaborated on with Nico Muhly and Sufjan Stevens. He and Aaron both speak of recording and releasing a version of the Long Count, their collaboration with visual artist Matthew Ritchie; the only trick is the logistics and expenses of getting guest vocalists like Berninger, My Brightest Diamond's Shara Worden, Kim and Kelley Deal, and Tunde Adebimpe in the same place at the same time.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=FW18gkDAPRE[/videoembed]

"It's actually been easier [transitioning between roles] now, since the National has gotten bigger," he reflects. "I think because now we've been away, we are who we are...we're not really worried about associations, or the types of scenes, or whatever it is." Indie fans don't always know of Bryce's classical work, just as people in that world know him as a composer, not "that guy from a rock band who also composes." It allows Bryce to shift between worlds, to take a breather from the apparatus of a scrutinized indie band, with the whole elaborate tour setup, and go play in small venues in Europe. Still, his temperament affects both, allows each half to become something unique it wouldn't quite be otherwise. Sometimes, he's writing music thinking it's for one purpose, and then, a different one reveals itself; "Squalor Victoria" and "Hard To Find" both began life as classical compositions he was working on outside of the National. "The 20th century idea that high art and low art, somehow, are separate ... I don't think that the audience really distinguishes that much between [them]," Bryce says. "For me, I just don't waste time worrying about it."

Among other things, Aaron's primary work outside the National is as a producer. Up until recently, that life was closely identified with his studio at his house in Ditmas Park, to the point that Mumford & Sons named a song on their most recent album "Ditmas" after working with Aaron there. It's also a spot deeply connected with the National, as the site where they recorded High Violet and Trouble Will Find Me. Just as the Brooklyn music scene that birthed the National has changed drastically over the years, their relationship to these places in the borough is changing, too; Aaron has put the house up for sale, and it's on the market for $2.35 million vs. the $735,000 he paid for it in 2004. From here, his base will be the larger studio he's building at his home in Upstate New York.

Recently, his main project was producing Frightened Rabbit's fifth album. "I'm much more musical in my approach, as opposed to engineering," Aaron says, describing how he functions as a producer. Sometimes he simply winds up working with people "out of friendship, or happenstance"; it happens when he sees music he believes in, music that he feels could be interesting, or when he sees an artist at a certain level and says, "I like your music and I can help you." That's how one of his most notable production credits -- Sharon Van Etten's 2012 breakthrough, Tramp -- came to be: Van Etten got in touch after Aaron, Bryce, and Justin Vernon covered her song "Love More" at MusicNOW and Aaron thought they could make a great record together. Aaron is a hands-on producer, and Frightened Rabbit is an uncommon project for him to take on. Aside from Mumford & Sons' last record, Aaron tends to work with artists who are more under the radar, not yet very established -- whether that means they are still carving out the specifics of their musical identity, or whether that means they haven't quite received the wider attention they deserve just yet; artists like Luluc, This Is The Kit, Little May, pre-breakthrough Sharon Van Etten. Frightened Rabbit are several albums into their career, and they've long since figured out the thing they do and how to do it well. But Aaron still pushes and pulls them when I watch them record, issuing directives to Scott Hutchison on a new guitar track he's laying down, or to Grant Hutchison about the rhythm of the tambourine part he's drumming out.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=hYgyQ20TJAs[/videoembed]

"I'm always making a lot of music, some of which filters into the National and some of which I filter into other things," Aaron explains. The specifics of his role in the National or outside of it, as producer, is that he comes off as crucially insightful as to what the essence of the songs in front of him should be. What the material wants to become. You watch him at work -- finding his way into a pre-existing Frightened Rabbit song, or talking about National material -- and you get the sense that he sees some kind of code within songwriting, has some deep understanding of how to build these things up from nothing, but also how to drill in and rearrange them, to layer them up and tear them back down accordingly.

For all the members, these other activities can initially derive from the National's world, and then influence the National when they all return; they take a breath, work with other people, and then bring some new element into the National after the fact. Much of the band's 2015 has been occupied with these other lives, and while some of these projects have yet to see release, the band members are now reaching the moment when they come back together, when the expansive network and interests of the National begin to scale back down to the five of them in a room, dreaming up the next thing.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=_Axr6d6G1DU[/videoembed]

IV. RIPPLE EFFECTS

Wearing a white cap and yellow-greenish-tinted sunglasses inside, Scott Devendorf sits down across from me in the concrete-and-wood interior of Threes Brewery in Gowanus, Brooklyn. This, too, is a neighborhood that has some prominence in the National's lifeline. Though they're known as a band from the Williamsburg era of indie, the National always occupied lesser-charted corners of the borough, hanging just to the side of the epicenter. It was Aaron's house in Ditmas, it was Berninger's apartment deeper into this neighborhood, across the canal.

"It was pretty industrial at the time," Scott says, describing Berninger's old street amidst a wider remembrance of the town they'd occupied over a decade ago. "There was an industrial milk delivery situation across the street. There were frequent car fires," he says with a grin.

Things have changed. The bar we're sitting in is the kind of place welcoming to 30- or 40-something parents having a drink while their children hang around, or where patrons look and act like they're going to a wine-tasting while partaking in a tongue-in-cheek beer connoisseurship with house options like I Hate Myself and Paradigmatic Flexibility. When I meet with Matt in Manhattan, it's in circumstances that similarly underline the changes in their lives paralleling the passage of time in the New York they once knew. He's visiting from his new home in Los Angeles, and we sit in the restaurant of a pristine hotel in the Financial District, staring out the windows at the new World Trade Center. On one hand, the years and miles removed from the National's roots are palpable. It's a New York that's shinier, more imperial. On the other hand, the specter of 9/11 still dominates this part of town, and the post-9/11 years -- the years so integral to the band's identity -- are also palpable.

When I meet with Scott in Gowanus, it's because one Wednesday a month, he comes in from his home in Long Island and hosts a Grateful Dead DJ night, where he puts together a playlist for a few hours and then a cover band takes over around 9:30. It's a casual thing he does that began as a joke with a friend who's involved at Threes, but then came to fruition. Scott figured it'd be fun to do a Grateful Dead DJ night, because he was in Grateful Dead mode. The project that, to varying degrees, has dominated each member of the National's lives for the last few years is another Red Hot charity compilation -- inspired by the format and success of 2009's Dessners-produced Dark Was The Night -- where they've gathered a ton of indie artists to cover Grateful Dead songs.

"It's going to be a thousand-dollar box set the size of a coffee table," Bryan jokes when we discuss the project at Eaux Claires. And if that festival's lineup read like a family affair, the tentative tracklist of the compilation underlines the reach of the National. Sharon Van Etten and Justin Vernon appear, naturally. Last year, I was in the studio with the War On Drugs when they recorded "Touch Of Grey" for the compilation, which sounds like it could be a Lost In The Dream outtake. One of the last things the Walkmen did before their indefinite hiatus was offer their take on "Ripple," a cover Scott says is half very Walkmen-esque, half very much a traditional reading of the track. Marijuana Death Squad's "Keep Truckin'" sounds vaguely like TV On The Radio. For that matter, Tunde Adebimpe sings on the compilation's version of "Playing In The Band." Unknown Mortal Orchestra channel Prince on "Shakedown Street." Kurt Vile did "Box Of Rain," a version Aaron calls "very authentic ... For a second, you're like 'Wait, is this from American Beauty?'" Perfume Genius has a song. Even Fucked Up is on this thing. Daniel Rossen from Grizzly Bear sings on two, including a faithfully lengthy rendition of "Terrapin Station." Matthew Houck, of Phosphorescent, sings "Standing On The Moon," a latter-day song written from an aging perspective, meditating on life. "[You] get a sense of mortality," Aaron says, comparing it to Dylan's "Not Dark Yet" before adding, "Some of these performances from these people are some of my favorite things they've ever done." And they reached back to a different generation of indie, to the artists that influenced them and the others on the compilation: Yo La Tengo's Ira Kaplan, Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo, and Stephen Malkmus all appear on the compilation as well. J. Mascis plays on "Box Of Rain" with Vile.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=vKA6NZ_Hbuk[/videoembed]

For the National's part, they've been involved integrally along the way, beyond curation. The band itself brings the Dead's version of "Peggy-O" into their own world, delivering it full of smoldering contemplation. "It's my favorite vocal performance [Berninger's] ever done," Aaron says. Many of the songs were recorded in a church in Woodstock, and many were recorded by a sort of house band assembled for the purpose of backing up singers who might not know the Dead as well, or whose own bands might not have been available. With the Devendorfs as the primary Dead Heads in the band, they played on a ton of material. "The stuff we did was obviously great," Bryan jokes, before adding, "Some of the interpretations of the songs, you hear it, and you go, 'My god, this is fucking killer.'"

"I think the stuff we did is very consistent musically, leaning more towards the originals," Scott says of the backing tracks they recorded as a house band, which he estimates to be in the neighborhood of 25 or so. "And then some of the covers are really out there and totally different." Some sound like country songs; some are jammy, but in a space-rock kind of way.

After being in the works for several years, the Grateful Dead compilation will likely see release early in 2016. There are a ton of moving pieces, which is partly why the project has taken so long to come together. More and more people were interested in contributing over time, and now that they have the amount they have -- somewhere in the neighborhood of 70 contributions -- Aaron questions how it could be anything but expansive: "You can't call it at 30. What 30 tracks?" Scott points out the balance of trying to hit certain legendary songs while also doing something interesting and elucidating with the band's catalog. "It's almost like, for some of these songs, making an album in itself," Aaron says of the difficulty in arranging the whole project, logistically and creatively. "But it's fun -- [the Dead] made some good studio records but it wasn't their thing. So, to actually shine a light on these things, and to do it with a lot of care and to see how excited all these musicians are ... literally, there's everyone. I mean, you'd be shocked at all the people."

As Scott's DJ set starts, he moves through this week's playlist, letting me sample compilation tracks on a separate pair of headphones. I think about how this entire project is a testament to what the National have achieved in the ascendent decade that led to 2015. There are other bands, perhaps, that could mount such an endeavor. But no other band feels as much like a conduit at their position -- the expansiveness and openness of their collaborations is what leads to this kind of thing, where they become a kind of hub through which so much of the surrounding indie world passes in and out. Even bigger than that: I can't think of another band with the right stature and reach and disposition to entrust with a project as involved as this. In essence, they've become arbiters of a certain slice of American music heritage.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=AqPkrnTxm64[/videoembed]

V. THE NEXT CHAPTER

Trouble Will Find Me felt like the end of something. The way the National's career progressed, a certain arc developed. The first two albums were sketches, prequels to a bigger idea, and then Alligator began to introduce the band we came to know, the ones so adept at cataloguing the anxieties of American life in the 21st century, city life, the inherent struggles of human relationships. The sound grew and became refined, and Trouble Will Find Me felt like more of a summarizing epilogue to the preceding three albums than a significant stylistic step forward. Both musically and thematically, Trouble Will Find Me seemed to represent everything the band was about over the course of their rise, and it was also the final note in solidifying their status in the indie rock world and beyond. "Trouble Will Find Me is definitely a bookend to a period of time," Scott says.

"What I'm excited about is, those four records are kind of four volumes of something," Bryce describes it. "And it feels like, maybe, what's about to happen is something really different."

This year, the band met for writing sessions -- once in L.A., and once Upstate -- so it's still too early to tell exactly what the album will become. (Though they did offer a public preview by playing a new song, first called "Roman Candle" and then switched to "Checking Out," last month.) But going into it, there are certain ambitions and interests for what the band hopes it will be. At this stage, there are two main impulses that hint at where the album could end up: (1) They want to write together as a band, and (2) they're interested in stripping it back and writing more direct songs. "We're not afraid, I think, to write hooks now," Aaron says. "Whereas in the past ... there's certain songs we'd try and then throw away, never really figure out." Now, he adds, there's a drive to write songs "that just pull you in, and then you're off."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=IDi7eE3y_JM[/videoembed]

After the dense layers and arrangements of the last few records, there appears to be a sort of back-to-basics ethos in the air. The results, so far, seem to have them invigorated. They walked away from the first writing session with a lot of new ideas. Fifteen tracks, Berninger estimates. Fifteen tracks that he feels are "very fucking amazing songs." Speaking of the process so far, Aaron betrays a bit of emotion, a little surprise at what they've come up with: "Why didn't we do that 15 years ago?"

When I meet with Aaron in his studio, he scrolls through his phone and plays me a handful of sketches the band's been working on. All are immediate and clean in a way that almost harkens back to Alligator. One track has a loping, sunny guitar line over calm organ, and a wistful Berninger toying with his higher register; it's a more peaceful sounding kind of revery than their melancholic musings of the past. Another explicitly sounds like a throwback to the uptempo stuff on Alligator, full of the cascading interlocked guitars the Dessner twins have perfected. In the very brief snippet I hear of a third song, there's a hint that the Grateful Dead project has left its mark on the band -- its drums and riff have a looser strut than almost anything I can think of in the band's catalog. The term Aaron throws out is that a lot of the new stuff is "a bit razory," before adding "It might be a little bit brighter, but it's also a little bit harsher." Nothing he plays me betrays the latter direction just yet, but the band's desire to do something "brighter" or somehow a bit poppier is already evident. The glimpses I get of what they're working on have a sprightly effortlessness. The band sounds less burdened.

"I think we're actually writing in a room together more than we ever did," Berninger says. "We're excited about that. It's changing the National, the way we're doing it." He recounts that when he and Aaron lived in the house in Ditmas Park, they were trading ideas via email; Berninger would be upstairs in his apartment working on lyrics and melodies and sending ideas down to Aaron and the rest of the band when they were jamming in the studio. Now, the band sets aside these retreats, times where it's the five of them getting to the core of something.

"When the record is finished, it's my favorite record for like, three months," Berninger says. "That's all I listen to -- with my headphones, drunk in the backyard, singing along."

***

There were disconcerting times when it seemed as if a moment like this wouldn't be possible for the National. The band has been candid in the past about the difficulty they had working together, the stress and fights that are far removed from the comparative tranquility of today. "We used to fight like fucking crazy," Berninger remembers. "[Aaron and I] were dicks to each other." Some of that is just the inevitable growing pains of a group of five personalities coming together and trying to sculpt something out of all their mingled inclinations and thoughts. There's no easy element to that process. But, as Berninger points out, that's also the stuff you have to get through -- that violent tension yields music with staying power. Over time, they learned how to navigate it better, and life was changing anyway. A few of them cite becoming fathers, starting families, as the thing that helped them put it all into perspective. They achieved more success and recognition around the same time. Eventually, there's that realization that if this is a job you get to do, it's worth all the other shit to keep it going.

"The band has taken its toll on everyone's personal lives," Bryce says. (He's the only member of the band who's not married with children.) "In a way, there's a feeling of time having passed." Berninger points out the grind of touring, and that none of them necessarily wants to be that classic-rock band up onstage as grandfathers. Those same families and lives back home that now put the band in perspective, make it more enjoyable, are also the things that eventually could become more of an anchor. You get the sense from these five men that they could happily walk away from indie-rock stardom to be parents in the suburbs. "I definitely think we'll stop before our records stop feeling exciting to us," Bryce allows. "But there's no talk of that right now."

All that being said: At this point, they've learned lessons about how they function as a band and how to move forward. "The National is always pushing it until the wheels are just about to come off," Berninger describes it. "[But] we know when the pressure is getting dangerous, and we learned that a long time ago." The National came close to the brink in the past, but it isn't the case anymore. A crucial part of that is how they've grown and matured as people, but another integral aspect is the band members' external collaborations. They're vital to the National's existence. Berninger describes it as a process of opening the windows, breathing in some air. "The biggest reason I had to do EL VY was because I didn't want the National to fall apart," he reflects. The end result is that they can come back and start fresh, as if after a slow-release reset button.

"We're actually healthier now than we have ever been," says Bryce.

"I think we're enjoying it more now than we ever had," Berninger concludes.

The phase they're entering now is one in which they all have ambitions percolating, hopes on what the next chapter of the National holds. Scott wants to do "something different and new," citing the influence of everyone gaining a "fresh perspective on things." Bryce talks of how excited he is for this to be a "great band record," referring to how they've grown as a live band; he also wants the band to explore more folk-oriented music in the future. "I think we might feel less pressure, actually," he says, reflecting on the rise of the band over the last few albums. "With Trouble, there was a feeling that we had, [that] we were only relating to ourselves now, somehow. Like there was some history there."

Aaron wants the band to experiment more formally. He still thinks they have better songs in them, and he wants to revisit things they've tried in the past but never followed through on, maybe like writing those hookier songs. "There's no fear, basically," he says, echoing Bryce's sentiments about the band only relating to themselves now, and echoing the notion they all seem to hold that the band is in such a stable place now that they can challenge themselves.

"The gravitational pull of the National brings us all back together," Berninger says. "It's not because we need to, it's [that] we actually can't wait to get back together. I know that every time the National gets in a room together after we've been apart, everybody is in a great mood. Everybody's kind of anxious to dive back into the next record. And I would say: There's never been a moment, there's never been a single second, where I was not excited about writing another National song, or working with those guys."

The last few years have been a time of transition -- the members moving, having their lives take on new forms, changing the way they approach the band and how they work. It's a process that's led them to a good place. To hear them all speak about it, it might be the best place the National have ever been.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=Ds_O25Dxk94[/videoembed]