Bruce Springsteen admits the '90s were his "lost period." "I didn't do a lot of work. Some people would say I didn't do my best work," he told Rolling Stone in 2009. And it's true. That decade occupies a strange space in Springsteen's career. He had broken up the E Street Band: his gang; a backing band legendary enough on their own that they are crucial characters in orbit of a person billed as a solo artist but still in need of the group to flesh out his story. "I lost sight," he said. "I didn't know what do next with them."

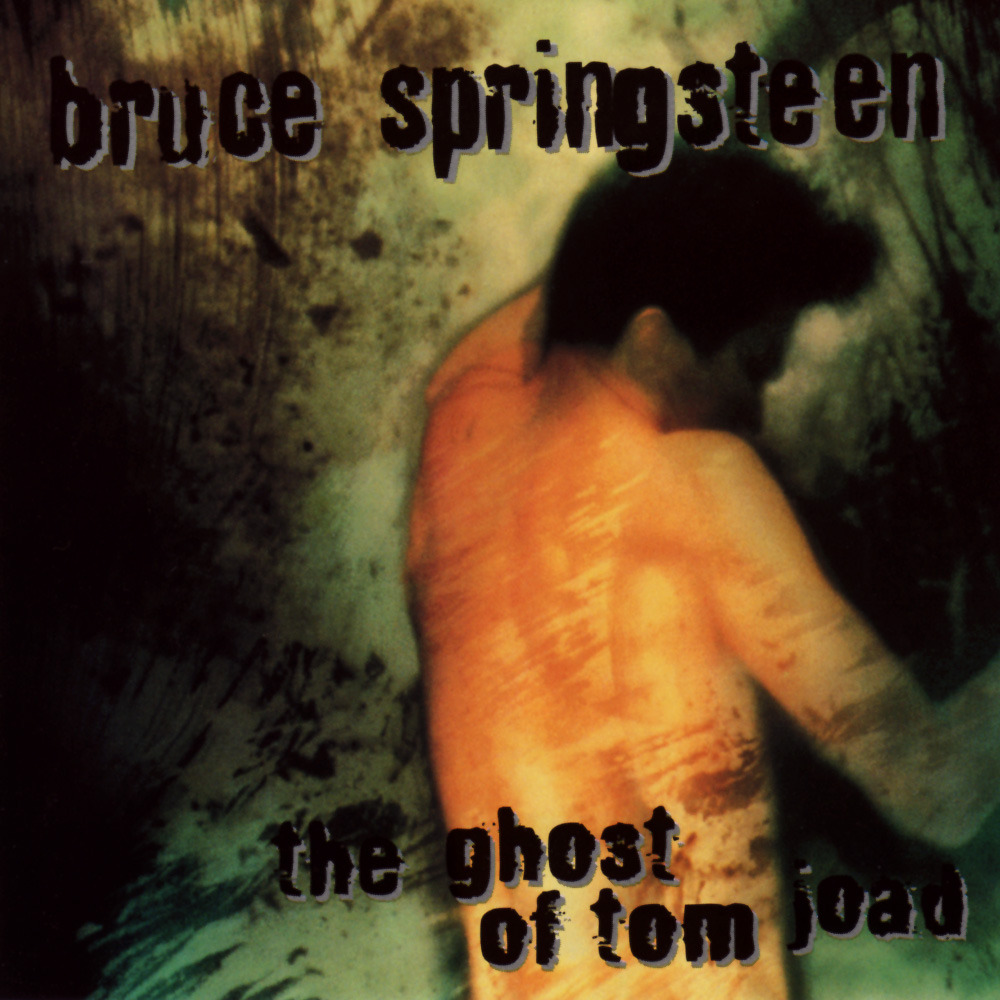

He was living in Los Angeles for a chunk of those years, something that -- as an icon so inextricably tied to the working class in New Jersey -- felt tantamount to betrayal. Springsteen seemed unmoored. The '90s followed the stratospheric success of his '80s, and they preceded the return of Bruce & E Street when their fans most needed them, in the fraught times of 21st century America. In between, not much happened. It was his least prolific decade. After 1987's Tunnel Of Love, it took him five years to produce a follow-up, and then he produced two: dual 1992 releases Human Touch (of "we don't speak of this anymore" quality) and Lucky Town (actually better than its mostly forgotten status would suggest, but it does sound like Springsteen imitating himself at times). He was still working on music throughout the rest of the '90s; he shelved a planned 1994 album reportedly titled Waiting On The End Of The World, which supposedly experimented with synths and loops in the way of "Streets Of Philadelphia." The only other album that actually did come out in the '90s was The Ghost Of Tom Joad, which turns 20 tomorrow.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Twenty years on from Born To Run, and just over a decade after Born In The U.S.A., here's the Bruce we had: the people's Tri-State Area prophet, living in a self-imposed exile across the country, making a sparse folk album about the American Southwest. It's an outlier in his catalog, and considering the expansive scope of his classic albums, there's no getting around that its smallness and restraint make it one of his more minor releases. That being said, it's also better than I remember it being. With two decades having passed, it's more important in Springsteen's career for the shifts it sits amongst and for the comparison points it provides than as an installment itself. But it was well-received at the time. In 1997, it won the Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album -- not that such an "honor" means a whole lot, per se, but still. Maybe it's aided by the fact that we now know this album was the epilogue to the wilderness years, that the return of the Springsteen we knew and loved -- the one who could captivate stadiums full of people, the one who had the vision to make the big statements about our country -- was imminent. With the hindsight that The Ghost Of Tom Joad didn't mark a permanent middle-aged turn towards reclusiveness and smaller ambitions, it's easier to enjoy on its own terms.

Most of the album is built on quiet acoustic guitar patterns, often weaving their way through near-ambient synth backdrops, with Springsteen employing his reedier whisper-sing approach. These are story songs and message songs; the vocal melodies and guitar parts are secondary to the lyrics and the ideas they want to convey. Which is part of why it's hard to wrap your head around as a Springsteen album, considering that his other turns toward more intimate or sparse music still boasted sharp songwriting and evocative vocal parts. I long remembered The Ghost Of Tom Joad as the Springsteen album without any real melodies. That's overly harsh, but I'll stand by part of it: The way in which The Ghost Of Tom Joad surprised me upon returning to it is that it's better as an album experience than I recalled. You still wouldn't necessarily single out many of these tracks and throw them on a playlist when you already have a lot of immortal material to choose from. With so many of the songs progressing in the same way -- guitar, vocals, entry of synth textures, maybe another embellishment or two as the song goes on -- the ones that linger most are the ones that flesh themselves out the most ("Straight Time," "Across The Border") or the ones that achieve a pretty bleakness ("Highway 29"). There are two essential Springsteen songs here: the title track and "Youngstown." Not surprisingly, those are the two that have the most distinct melodic power, and the two that have the most instrumentation. (Still, both of these songs really come into their own more fully in any post-reunion full-band interpretation from the E Street Band than they do on the album.) They still achieve the storytelling angle the album focuses on, but feel like more emphatic statements, with the title track in particular being one of Springsteen's best interactions with classic, mythic Americana.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

There is a lineage within Springsteen's career in which The Ghost Of Tom Joad exists. Its obvious antecedent is 1982's Nebraska, the acoustic album of 4-track cassette demos that Springsteen released between The River and Born In The U.S.A.. The Ghost Of Tom Joad formally is the same in the sense that it was the next time Springsteen went this stripped down, but it isn't haunting in the same way as Nebraska; it doesn't have the same late-night highway horror-stories vibe. It's more of a wasteland meditation on specific political and social issues, like the lives of undocumented immigrants or the struggles Springsteen saw and related to in Mexican-American communities during his time in Los Angeles. It's more closely related to 2005's Devils & Dust, the third in the family; they're the Western albums. (Much of the material on Devils & Dust originated during the The Ghost Of Tom Joad era, but it's a superior album because it's loaded up with a handful of the most underrated songs on any of Springsteen's records.) The Ghost Of Tom Joad is the weakest and least essential of the trilogy, but you can't get from Nebraska to Devils & Dust without it. It's the conduit at the center of the trilogy, through which Springsteen's intimate short stories find their way to a new corner of the continent.

That, more than anything, is what keeps The Ghost Of Tom Joad an outlier amongst Springsteen's other work, despite having these relatives. Place plays an integral role in the man's music. Obviously. Whether boardwalk fantasies on his earliest albums, tales of realist violence or fractured Romanticism on the highway, or gritty depictions of rote, broken-down suburban lives, Springsteen's visions of New Jersey -- and the American landscape surrounding it and just past its horizon -- are one of the cornerstones of his work. Even an album named Nebraska and represented by a black-and-white photo of the Plains is a Northeast album when you get down to its ethos. But The Ghost Of Tom Joad is a desert album, the first work he'd made that had a distinct location (and personality derived from that location) that diverged so clearly and sharply from his roots. It comes out of his L.A. years; times where he would ride his motorcycle through the Southwest. (The other L.A.-life albums -- Human Touch and Lucky Town -- are outliers, too, but more so because they're the Springsteen albums that fall into generic signifiers and seem to have no sense of place.) It sets the stage for Devils & Dust nearly a decade later, but that album filtered the same kind of Western stories through a title track that sets the stage in the era of the Iraq War, and thus offered broader grappling with America.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The Ghost Of Tom Joad, on the other hand, is the rare insular Springsteen album -- hyper-specific to its locale and the small-screen stories it wants to relate. Even as "Youngstown" begins "Here in Northeast Ohio...," it's meeting with "Sinaloa Cowboys" at the sonic crossroads of the Southwest, breathing in the same dust. It's one of the only times in more than four decades that you can hear Springsteen truly and totally out of the context we know him from. He's in a completely different landscape, solitary, and drawing very different ghost stories out of that ground than he did on Nebraska. The fact that it's skeletal and hushed is necessary to it, even if it means the standouts here don't have the same staying power as the highlights from his other desert album. (I'll take Devils & Dust's "All The Way Home" or "Maria's Bed" or "Long Time Comin'" over just about anything on The Ghost Of Tom Joad save perhaps the title track and "Youngstown.") But Devils & Dust was looking to do something else; even when it slows down, it has the sound of a man barreling through the desert kicking up a cloud behind him, searching for something as he traverses from one coast to another. The Ghost Of Tom Joad is content to sit and contemplate in the cruel exposure of a blinding day. It stares out at the silent expanse of the desert, the only place where this music could be thunderous, since even whispers crash loudly out in desolation.

Though in all its quietness it'd be easy to say that the album hardly leaves its mark on Springsteen's catalog, it sits at multiple turning points. It's that end to the wilderness; after the awkward 1995 attempt at an E Street reunion, the band did get back together for a triumphant 1999-2000 tour that set the stage for the Springsteen of the '00s. The Springsteen who, having rediscovered his voice and power in rock music, issued a series of State Of The Nation albums tracing the experiences of this century. In a weird way, The Ghost Of Tom Joad sets the stage for that thematically, too. During Springsteen's classic era, he caught the ethos of the times in very personal narratives; he rarely addressed a real political event explicitly. Here, he began to hone that voice in little sketches, priming himself for the heavier lifting to be done when an American icon was needed to chronicle 9/11, or the Great Recession, or all of America's 21st century fallout on albums like The Rising and Magic and Wrecking Ball. As an entity, The Ghost Of Tom Joad isn't essential compared to the work from the decades before or after. But it's the one thing that we've heard from Springsteen's Lost Decade that works for what it is -- it's the sound of a Bruce that's more alone, a bit listless. Even if its importance in his catalog is as a standalone, transitional chapter, it's an important plot point in getting from '80s popstar Bruce to '00s aging bard status. That alone makes it a strange and notable installment in the imposing canon that is Springsteen's body of work.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]