Last Friday, Ryan Adams' 29 turned 10. It isn't one of Adams' essential works, but its anniversary is notable because it's the third Adams album to turn 10 in 2015, following Cold Roses on 5/3 and Jacksonville City Nights on 9/27. In terms of albums that actually saw official release, the '05 trilogy represents the most prolific period of an artist always defined by the sheer amount of music he produces. Not that Adams has ever really slowed down by the standards of most artists. This is the guy who "quit" music in 2009 and released a double album of outtakes (III/IV) the following year, and a new album (Ashes & Fire) a year after that. Since going solo with 2000's Heartbreaker, the longest Adams has gone in between releases was the three-year gap between Ashes & Fire and 2014's excellent self-titled record, which is, you know, the amount of time many artists take between every album these days. And since Ryan Adams, he also released his much-discussed album-length cover of Taylor Swift's 1989, a steady stream of singles/EPs through his label Pax-Am's Single Series, and already has more than 20 songs prepped for another record slated for next year. Between the rate (and, generally speaking, high quality) of all this material so far, it feels like Adams is in a resurgent period -- compared to the pacing of anyone else's career, it's a return to the Adams of 10 years ago, churning out music constantly. But the Adams who hangs out at Pax-Am all day, every day, just writing and recording whatever strikes him while jamming with friends, is not the Adams of 2005 or the years preceding it. One reason to mark the 10-year anniversary of Adams' '05 trilogy is that some of his best material is in there. Another is that the '05 trilogy was the end of one phase of Adams' career, and the end of the original version of Adams as we knew him.

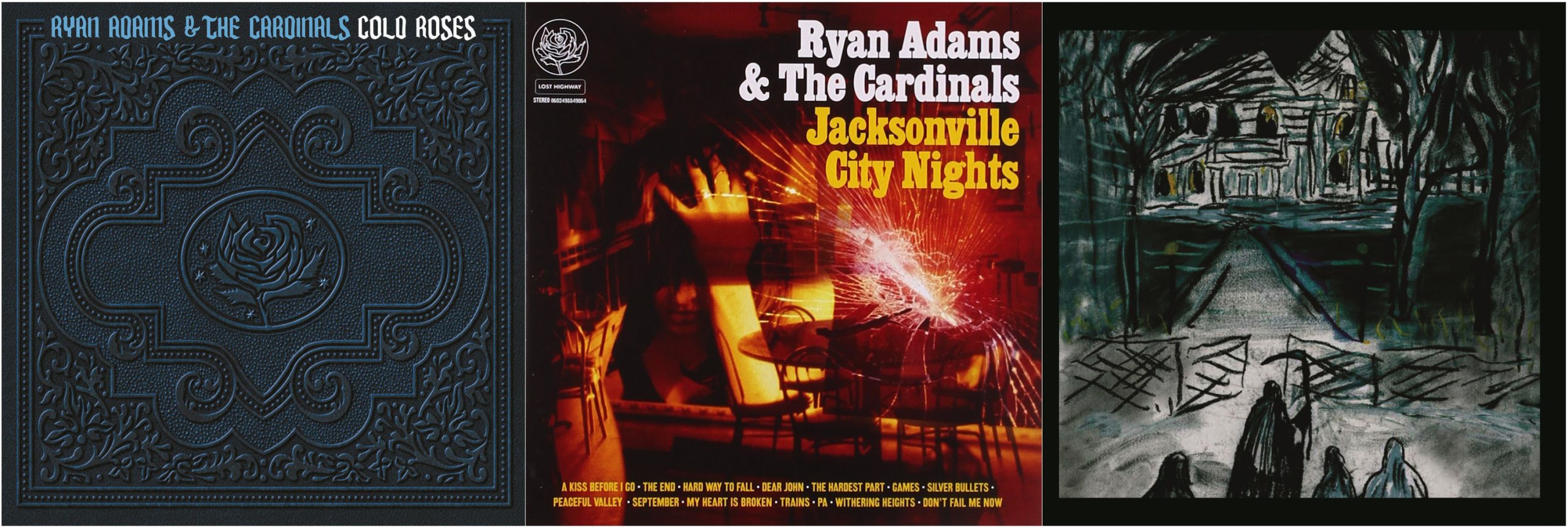

Through a number of factors, the Adams that came with Cold Roses in May '05 seemed to be refocused after a messy few preceding years. Following a disastrous wrist injury in early 2004, he'd slowly relearned how to play guitar through the pain (as well as reconstructive surgery and rehab work), which led him to a new, looser style of playing and writing. He formed his backing band, the Cardinals, which helped ground him as an artist for several years. And in terms of a media narrative, it was probably beneficial for Adams' standing that the '05 trilogy wound up, stylistically speaking, basically continuing in some version of the vein people had always wanted since Heartbreaker: Cold Roses was stoned, jammy country-rock, Jacksonville City Nights was straight-up old-school country, and 29 is hard to classify, but does have a kind of sparse, nocturnal balladry to it, not too far from Neil Young.

Adams is now 41, which means he was newly 31 when 29 came out, which in turn means he was 10 albums deep at an age where most of his contemporaries were probably hovering more around three or four. By 2005, it was an element that had contributed to the erosion of Adams' critical standing. When you look back at Adams' career, there isn't so much one downturn followed by a redemption or a steady second act catering solely to fans; there are actually a series of implosions of one breed or another, and albums dotted throughout that have vacillated in stature amongst both critics and fans. He was the wunderkind and the Next Big Thing in Whiskeytown -- Heartbreaker was already a "comeback" of sorts after that band stagnated and dissolved amidst their third album, Pneumonia, languishing in label hell. Gold, which was not the album Adams wanted to release after Heartbreaker but was nevertheless the album he released after Heartbreaker, is still one of the moments you can pinpoint in Adams' career where he'd garnered legitimate pop clout. And then things really started to go off the rails: He handed in Love Is Hell to his label, Lost Highway, who rejected it; he recorded the mostly hated Rock N Roll as, seemingly, some sneering take on more "commercial" music for the label. Lost Highway totally botched the release of Love Is Hell by splitting it into two EPs. By the time Cold Roses rolled around in May '05, Adams could already be perceived as a fallen figure: a man 10 years into his career who had nearly blown it up a few times over now, whether due to the media portrait of him as a petulant egoist or due to the dissonance between what he wanted to do and the perception of what critics and fans wanted him to do.

The repeated criticisms of his prolificacy -- the notion that it betrayed a crippling lack of quality control, or an unwillingness to settle on a coherent musical identity -- were thrown around. The persona he'd built up was one of self-satisfied hubris, lack of consistency, and at times flat-out temper-tantrum-aggression via infamous events like leaving irate messages on journalists' phones or stopping a show to kick a heckler out for requesting "Summer Of '69." When the '05 trilogy began, some doubters still rolled their eyes: This looked like yet another over-the-top lack of restraint, another function of that hubris. Instead, the '05 trilogy proved to be a beautiful set of three albums. Adams released 41 songs in 2005 -- several of which are essential and fan favorites, many of which are hidden gems amidst the ever-growing heap of his output, and none of which are overtly offensive. The reception to all this varied between each record and each publication, but generally speaking, the deluge garnered way more praise than vitriol, a sharp turnaround from where he'd just been. This was already another comeback, and the guy was only then closing in on a decade of putting out music.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

As far as the albums themselves go, Cold Roses was the big opening salvo. It's sprawling because it has a lot of songs (though the double-album conceit is artificial; all the music could have fit on one disc), and it's sprawling because it's Adams' loosest album. Even if Jacksonville City Nights is the '05 album comprised of first takes, Cold Roses is the one that sounds like you're hanging in a studio late at night while the band just plays. It remains one of Adams' finest releases. In the broader musical conversation, Heartbreaker will probably always be regarded as Adams' classic. But over the years, Love Is Hell and Cold Roses have come to rival it in fans' estimation. After indulging his Grateful Dead adoration on Cold Roses, Adams went as close to traditional country as he's ever been with Jacksonville City Nights when September crept up. Originally set to actually be titled September, Jacksonville is the autumnal middle chapter to the trilogy, an intimate affair built from Fall's burnt shades of yellow and orange. While it's not as close to the conversation about Adams' masterpieces, it's certainly in the upper tier of his catalogue.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

After two albums with the Cardinals, Adams finished the year solo. 29 is the relative outlier of the trilogy, and is still pretty much an outlier for Adams in general, even in a discography full of divergences and genre shifts. If Cold Roses conjures sunrises and dusty highway drives as much as it does a mythic Southern bar with a beer-soaked floor, and Jacksonville City Nights is that meditative autumn record in tribute to his hometown, then 29 is the somber, winter-night album, released squarely in the fleeting days of the year. It might not be quite as nocturnally melancholic as Love Is Hell, but it has a sparse, piano-based sound that Adams has never employed as thoroughly over the course of an album otherwise. It tends to be regarded as the weakest of the '05 trilogy, which is fair enough but is partially rooted in the fact that it was up against two substantial works in Adams' history. 29 is also one of the lesser-rememberedalbums of his in general, though, and that's the part that should perhaps be amended as it hits 10 years old. There are things that don't work: "The Sadness" is still a hard sell, and the reliance on piano-based arrangements mean that a lot of these songs take some time to reveal themselves. But overall 29 is one of Adams' most underrated releases, with a mood and tone unique amongst his other music, and stunning tracks like "Strawberry Wine," "Nightbirds," and "Elizabeth, You Were Born To Play That Part" anchoring it. You have to spend some time with it, but it has a lot more soul than the next several albums Adams released after the '05 trilogy.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

About what came next. In the latter half of the '00s, Adams got sober, did that whole "quitting music" thing, met and married Mandy Moore (they are now divorced), and was diagnosed with Ménière's disease, a rare inner-ear disorder that proved to be the source of many of his unsolved health problems. Collectively, what transpired over those years led to the more balanced, affable Adams we know today, and it also changed the nature of his output. Easy Tiger came out in 2007, the first since the '05 trilogy, and the big narrative with that record was the Adams was newly sober. And compared to the freewheeling and/or all-over-the-place nature of his career up until that point, Easy Tiger is different. In ways, it's the platonic ideal of an Adams record, the first time where you could imagine the project at hand was "Let's make a Ryan Adams album" vs. "Let's make an album in the style of the Grateful Dead or the Smiths." The steadiness stuck, through the similarly slick Cardinology and Ashes & Fire (another platonic-ideal Ryan Adams album, just a platonic ideal of a different Ryan Adams) through to the humid and infectious Ryan Adams.

Aside from being a creative peak in his career, the '05 trilogy is the final chapter in one phase of his career, the conclusion before that new Adams phase started up in 2007. There are consistencies throughout his career too, though. Most of Adams' albums are concept albums. They are arranged around a central influence or idea. Even Easy Tiger, as the "Ryan Adams" record, fits that mold, and the pattern continues with Ryan Adams (his '80s heartland rock album, with a cover aping Bryan Adams' Reckless) and his tribute to 1989 (which he describes as being in a style where Bruce Springsteen's Darkness On The Edge Of Town meets the Smiths' Meat Is Murder). There's an element of postmodern performance to what he does, trying on different skins each time, forcing himself into writing exercises to see what his voice can do in different contexts. This is what led to all those critics calling Adams a poser back in the day -- and when he was still a snotty would-be punk-rocker, sure, maybe. These days, Adams presents himself as a genuine music fan and unabashed nerd, likely a function of simply growing older and more comfortable with himself. If anyone dismisses Adams in 2015, it'd be because of his classicism, not his artifice.

You could chalk that up to there being less (or less obnoxious) artifice in Adams' music than in the past, or you could chalk that up to the fact that artifice is a basic element of our lives now, in a much more significant way than even in 2005. Adams' malleability is what we do every day, flitting between projections, filtering ourselves through our influences. Maybe it took us a while to take Adams on his own terms because what he does should be anathema in the super-"authentic" world of the theoretically confessional singer-songwriter. But that paradox is what makes revisiting Cold Roses, Jacksonville City Nights, and 29 so striking. The man tossed out three moving albums in a seven-month span, and a decade later there are still new things to reckon with, new ways to feel about him and his music. In a more significant left turn than any other in Adams' career, he now appears as one our most classicist artists, but a classicist artist built from and for the internet era: content to jettison projects, close and open the vaults at will, or overload us with material whenever, leaving it all for us to sift through amongst the years and noise that pass between it all.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]