Recounting the legendary rise of Arctic Monkeys a decade after the fact is almost embarrassingly millennial: a story so seemingly inconsequential in today's technological landscape that it's easy to forget how Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not -- which turns 10 on Saturday -- became such a surprisingly successful debut. I vividly remember that moment, though, because I was living in San Francisco, busy thinking that the album's single "Fake Tales Of San Francisco" was written just for me.

Arctic Monkeys came to Americans as four mop-topped lads from just outside of Sheffield by way of the internet. Not just “the internet,” but MySpace. As I write this, I imagine how I will explain MySpace to my children one day, and all I can think of is: “Shittier Facebook” or “Facebook with more emphasis on music” or “Facebook but you get to rank your friends.” Then I realize that I will never have to explain MySpace to my children, because they won’t even know what an MP3 is. We’ll have LCD screens for our eyelids by then. But for anyone who came of age in the mid-2000s, MySpace was a useful tool for music discovery, a site that gave rise to the increasing prominence of MP3s, and is partially credited with -- alongside Napster, Limewire and the like -- completely disrupting the music industry as we knew it. Now the music industry and music fans are deep in the trenches of the streaming wars, as purveyors of music attempt to monetize a product that is bafflingly easy to hand out for free. Arctic Monkeys might be one of the best contemporary examples of a band who became popular because they gave away their music for free when it wasn't all that common to do so. No one will deny that the internet changed the way we consume music, that we’re still dealing with the repercussions of rampant, unchecked piracy, but today, it’s pretty easy to forget exactly why.

Arctic Monkeys aren’t the only band to “blame” for this change, but they are one of the easiest bands to point to as file-sharing pioneers. Popular acts of the aughts came to prominence while the internet was being streamlined. Blogs (not unlike this one) were taking over as preeminent tastemakers, and file-sharing services became prevalent enough that they demonstrated a significant danger to record labels long dependent on album sales. Here's the thing: People like to think that they're discovering something without a branded qualifier attached to it. MySpace helped young people feel like they were early to a band, like they had a hand in making that band a known entity.

As someone who came of age amidst this landscape, I tend to trace this transition back to the 2001 film Josie & The Pussycats, which boasted one of the most enviable girl squads imaginable: Rachel Leigh Cook, Tara Reid, and Rosario Dawson. Together they form a small-town rock band, the Pussycats, who sign a major-label deal with the fictitious MegaRecords after being discovered virtually overnight. They later discover that MegaRecords is in cahoots with the U.S. government, inserting subliminal advertising into their signees’ albums, which in turn made youths of America want to go buy shit that they didn't need. It’s a silly movie with a fairly serious message: We should consume art because we genuinely like it, not because it’s being sold to us. Discovering music for yourself matters. Personal taste matters.

Josie & The Pussycats excels because it is self-aware. Carson Daly makes a cameo, playing a villainous version of himself as the host of Total Request Live. DuJour, the boy band that the Pussycats replace, is an obvious nod to *NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys. It perfectly encapsulates that moment of my youth when teen culture was being sold to me in an inescapably obvious way. You are what you consume, etc. But whether or not it was intentional, Josie & The Pussycats anticipated a shift in ideology as to how a band's brand could be sold, echoing the very real fear that fandom was being sold in ways that took away people’s agency as thoughtful consumers of culture. "Poser" was a really important word back then, one that I don't hear as much anymore. Of course now there are campaigns designed to imitate groundswell; remember the Arcade Fire's "guerrilla" marketing efforts or Katy Perry's graffiti around Brooklyn.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Beneath The Boardwalk could technically be considered Arctic Monkeys’ first release. It’s a collection of 18 demo songs that the band pieced together in 2004, when they were playing shows throughout Sheffield and trying to make a name for themselves. Those songs were burned as mix CDs to be distributed at gigs and around the city. Fans uploaded those demos to file-sharing sites, and legend has it that friends of Alex Turner and co. would go as far as to leave Beneath The Boardwalk CDs on public busses, so they could be found by unsuspecting soon-to-be fans. Many of the songs, including"Mardy Bum," "I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor," "Fake Tales Of San Francisco," "Dancing Shoes," "Still Take You Home," "Riot Van," "When the Sun Goes Down" (formerly known as "Scummy") and "A Certain Romance" were also all available for download online, free of charge.

This system of distribution would later be credited as a “marketing tactic,” but it wasn’t. Arctic Monkeys got their name out there by giving away their material, which might’ve been considered little more than a financially “stupid tactic” but it follows the same pretense as giving away a free trial on Apple Music. Hand out your art and expect returns once people are hooked on the product. It’s a fairly basic, DIY system of distribution, but it's one that made Arctic Monkeys an extremely popular band before they even had an official, professionally recorded debut.

Naturally, that grassroots rise made Arctic Monkeys a desirable band to sign. They were a young band with an already established fanbase that wouldn’t require that much attention or PR boosting; fans would readily buy their debut without a campaign to sell it. They were a success before they had even officially released anything, and there are countless articles that refer back to their first festival sets at Reading and Leeds in 2005 (the Killers, Foo Fighters, and Iron Maiden all headlined that year). Significant crowds gathered for a group who had never signed to anything, which was and still is surprising. Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not was preceded by a debut EP titled Five Minutes With The Arctic Monkeys. The band's debut single was “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor,” a song that The Guardian recently claimed changed the music industry. “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor” quickly made it to the #1 spot on the UK singles chart, which was unexpectedly huge for a band who had only just signed a label deal.

Domino Records wasn’t the powerhouse indie that it is today back in 2006. In fact, its rise is due in part to its decision to add Arctic Monkeys to their roster, alongside Franz Ferdinand and the Kills, during a time when British music was selling well in the States. Arctic Monkeys’ intense Englishness -- Turner’s accent and lyrical lingo, song titles like “Mardy Bum” and mentions of “sexy little swine” -- lent itself to a very distinct kind of objectification in America. Regional references don't matter much when you're discovering something by way of the borderless web.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The same year that Arctic Monkeys were playing shows around Sheffield and handing out CDs at gigs, Franz Ferdinand released their debut single. “Take Me Out” might not be a seminal song to a lot of people, but it’s one that soundtracked a year of my youth, a song that was virtually inescapable in 2004. The Scottish band also represented a card-carrying British aesthetic that lent itself to the era. Amy Winehouse would release her critically acclaimed sophomore album, Back To Black, the same year Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not came out. Lily Allen -- another artist who owes her career to MySpace -- debuted her ultra-confident, sassy Alright, Still in 2006 as well. Lady Sovereign, with her ongoing mentions of chavs and tracky bottoms (pants that were also name-checked in "A Certain Romance"), would release “Love Me Or Hate Me” in 2006, too. (It was perhaps one of the most confounding and ill-aging singles I can still easily sing along to in 2016.) The Libertines had just ended their seven year run in 2004, and there were people who momentarily considered Arctic Monkeys' rise to be an indication that we were facing The Return Of Britpop. We weren’t, but there was a considerable uptick of American interest in UK artists. A lot of those aforementioned acts, with the exception of Winehouse, didn’t have the same staying power, though.

At the time of its release, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not was the fastest-selling debut album in UK chart history. This is an alarming fact for two reasons: 1) it proved that the band had managed to scrape together a huge following without ever putting out an official release, and 2) it clued a lot of people into the fact that the internet would, in fact, overtake music magazines as a means through which to distribute trends. Not just by way of blogs or online zines, but by self-curated individual music profiles. The album later went on to earn them the Mercury Prize, which solidified Arctic Monkeys as the biggest act to come out of England that year.

Arctic Monkeys’ debut single didn’t make them internationally popular just because they happened to have fans; a lot of small bands have a big, active fan base. But Arctic Monkeys had the unique brand of charisma that comes with being stoned, drunk, and bored the vast majority of the time when you're desperately seeking out some type of fun when you’re still a teenager. Turner was only 19 when “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor” came out, and you can hear that he’s just barely teetering on the edge of adulthood in much of Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’s songwriting (Turner turned 20 before its release).

"I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor" is a short, spastic love song, an ode to the awkward wallflower he's got his eye on whose shoulders don’t -- no, won’t -- move to the beat. It’s a not-so-grand tale of modern day romance that sounds-off to another, older one. “Oh there ain't no love/ No Montagues or Capulets/ Just banging tunes and DJ sets and dirty dancefloors and dreams of naughtiness,” Turner croons. But his croon is more of a bark, a lukewarm reminder that nothing about this storied romance is all that romantic, and somehow that inability to write fantasy made Turner kind of dashing -- because he was still just a kid. He was relatable.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

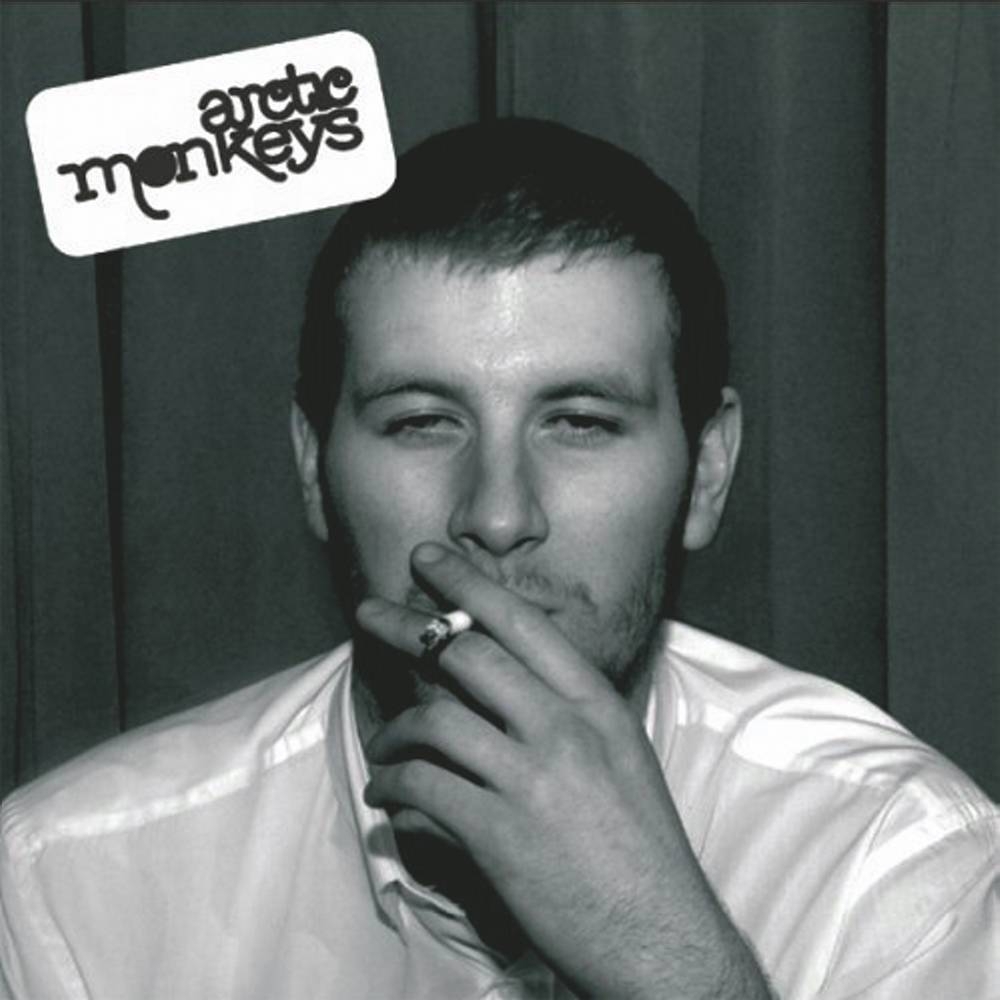

I point this out because Turner was and still is somewhat of an unconventional sex symbol. In 2006 he was the archetypal young reveler, the guy who never leaves the party early but will walk you home if you stay out late enough with him. He was bad (cue "Riot Van"), but he wasn't Pete Doherty-bad. When fans fell in love with Arctic Monkeys, they were falling in love with Alex Turner's distinct, brash attitude. It’d be a disservice to his image as a frontman to not point that out. They were a scrappy group of guys who instead of dressing the part of rock stars preferred polo shirts and indoor-soccer sneakers. They didn’t look like they were trying at all, which in most music scenes is the key to being instantly likable if you have a modicum of talent. It’s not surprising, then, that this truly was the album that made them a band worthy of people’s attention, because there’s nothing try-hard about it.

Arctic Monkeys would undergo a significant evolution in the years after they released their debut. “Flourescent Adolescent,” from their sophomore album, Favourite Worst Nightmare, addressed the growing-older complex that any rock band who makes it when they’re young inevitably deals with (“You used to get it in your fishnets/ But now you only get it in your night dress/ Discarded all the naughty nights for niceness/ Landed in a very common crisis”). Turner grew into himself like all of us do, and his songwriting did so at the same pace.

A lot of people who came of age alongside this band weren’t necessarily perturbed, but they might've been thrown off by Turner and Arctic Monkeys' current look (carefully coiffed hair, raw denim, leather jackets) when the band released its most recent album, AM. The group had moved to Los Angeles, and all of the songs on the LP sound like things that should emanate from a car’s speakers while you’re coasting down the highway. It’s a far cry from the scrappiness of their original form, but there’s still a wayward romanticism in it. “Why'd You Only Call Me When You’re High?” calls back to those early days, which solidified the fact that Arctic Monkeys didn't reinvent themselves, they just grew up. But for anyone who grew up with them, Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not was and always will be the one album that really mattered. It was formative for both of us.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]