Earlier this month the world's second-biggest concert-production company, AEG Live, announced the dates and location of its inaugural Panorama festival. The fest would be held on Randall's Island during the second-to-last weekend of July 2016. That announcement followed months of rumors, speculation, and public (not to mention private) outcry. Panorama has been billed as a New York City version of Coachella: convenient shorthand owing to the fact that AEG is also the company behind that festival -- the country's biggest -- among many, many, other things. Of course, New York City already has its own version of Coachella: the independently run Governors Ball, which turns six years old this year and will celebrate that birthday the first weekend of June, also on Randall's Island, with a three-day event headlined by Kanye West, the Strokes, and the Killers.

This isn't the first time AEG has tried to stage a festival in New York City. It happened once before, in 2008, and that one also conflicted with another pre-existing festival. That whole thing ended badly for all parties involved, largely because AEG made a terrible miscalculation when choosing a venue for their event. This time, though, they found the perfect spot ... but that didn't quite work out, either. Initially, AEG hoped to stage Panorama in Queens' Flushing Meadows-Corona Park over the third weekend of June, but due to a confluence of outside disruptions, AEG was forced to adapt on the fly. It's a compromise that satisfied no one: not AEG, who lost out on both the prime real estate of Flushing Meadows and the fine weather offered by New York City in mid-June; not Founders Entertainment, the company behind Governors Ball, who petitioned the city to reject AEG's proposal on the grounds that it was "an aggressive, greedy attempt by AEG to push a small independent company of born and bred New Yorkers out of business and out of the market"; not the Madison Square Garden Company, an ostensibly unrelated third party that got involved in the battle to protect its own interests.

The whole thing, though, is a bizarre and troubling story involving political manipulation and corporate sprawl: a story about the rapidly evolving landscape and shifting demographics of New York City; a story about a new mayor whose limited personal finances leave him vulnerable to the demands of lobbyists and deep-pocketed corporations. And it's an evolving story, too. Tickets for Governors Ball 2016 are on sale now, while Panorama's lineup still has yet to be announced, but already, there are questions about what the arrival of Panorama might mean for the future of Governors Ball -- and more insidiously, what the arrival of Panorama might mean for the music industry as a whole. And then, of course, there is the question of what it all means to you: the listener, the ticket-buyer, the concerned citizen, the consumer.

It's a murky, ugly, uncomfortable swamp, much like the summer in New York City itself. Let's wade in.

So like I was saying: They've tried it once before, in 2008. Back then, AEG's New York City version of Coachella was called the All Points West Music & Arts Festival, and it was held at Liberty State Park in Jersey City, New Jersey. It wasn't New York City, admittedly, but it was close enough. Right?

"It's probably the only green oasis like this near New York City that can hold the kind of crowd that we want to have," said All Points West co-organizer Ken Tesler in January 2008, when the then-new festival was first announced. "What better place than a beautiful park environment, looking at the Statue Of Liberty, Ellis Island, and the city skyline?"

The inaugural All Points West was scheduled for the weekend of August 8 - 10 -- coincidentally, the very same weekend that another Jersey-based festival was set to make its debut. That one -- the Vineland Music Festival -- had been announced in November 2007. It was being staged by C3 Presents, the same company now behind such festivals as Lollapalooza, Austin City Limits, and Shaky Knees, among others. Vineland would reportedly host upwards of 100 artists, and would be held on a 550-acre tract of private farmland in the city for which the festival was named -- Vineland, New Jersey -- about an hour's drive from three major metropolises: New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

The announcement of All Points West came nearly two months after the announcement of Vineland. Then, four days after the announcement of All Points West, there was another announcement -- this one from C3 Presents:

Vineland had been cancelled.

"Dead," proclaimed C3 Presents co-owner Charlie Jones. "That particular part of the country got too popular too fast; there are too many festivals in close proximity."

There weren't that many festivals in close proximity, though, were there? There was Siren Fest, which ran in mid-July, but that had been going since 2001. There was the CMJ New Music Marathon, but that ran in October, and had been going on for nearly three decades. Traveling festivals like Warped Tour, H.O.R.D.E., and Curiosa came through every summer, but that was nothing new; that had been part of the landscape since Lollapalooza kicked off in 1991. Meanwhile, till that point, the only real attempt to stage a New York City version of Coachella had been the ill-fated Field Day, which was an absolute disaster that died after its inaugural 2003 incarnation.

"Too popular too fast"? "Too many festivals in close proximity"? That wasn't a fresh diagnosis of the market; it was code for All Points West, for AEG.

Still, C3's decision proved prescient. The first annual All Points West festival lost money; it fell short of its total capacity by 20 percent, bringing in a little more than 75,000 people for an event that was intended to host 90,000. All Points West returned in 2009, but sold 4,000 fewer tickets in its second year than it did in its first.

Why, though? Why would a festival aimed at New York City audiences fail?

The problems were myriad. There was the problem of labor costs, which were much higher in the tri-state region surrounding New York City than they were in places like Indio, California (where Coachella is held) and Manchester, Tennessee (home to Bonnaroo). Then there was the problem of the byzantine alcohol restrictions enforced at New Jersey state parks, which limited customers to only five drinks over the course of an event that could go longer than 10 hours, and forced those customers to do their drinking in a small handful of fenced-off areas.

Said AEG's Paul Tollett, one of APW's co-organizers: "[New York City is] one of the toughest markets to do a three-day festival. When you do a show in the thick of a city, there's inherently going to be more restrictions. That's the trade-off of it being so close."

The old-school promoter Ron Delsner of Live Nation put it more succinctly: "There's no land, baby. There's not 3,000 acres. There's tunnels and bridges and millions of people walking around here."

That's partly why AEG defined "here" as "Jersey City." And Jersey City was the biggest problem of all.

"All Points West is an experiment that just didn't work," said AEG Live CEO Randy Phillips, in April 2010, when announcing that the festival would not return for a third year. "It's very hard to get New Yorkers to cross that river."

In 2012, Governors Ball doubled in size. They added a second day, brought in Beck and Passion Pit to headline, and moved the whole thing to the 433-acre Randall's Island Park -- which sits in the East River, adjacent to Manhattan, in the geographical center of New York City -- ultimately drawing 42,000 ticketholders. In 2013, the festival stayed on Randall's Island, but got bigger still: adding a third day, and offering Kanye West, Kings Of Leon, and Guns N' Roses as its headliners. This time, the event brought in a crowd of 135,000.

In the days leading up to the 2014 edition of Governors Ball, Founders partner Jordan Wolowitz told Billboard that he and his team had "cracked the code for putting on a successful contemporary music festival in the New York City market." He elaborated, saying:

People who had tried doing New York festivals in the past tried to do them in New Jersey or Long Island and call it a "New York City" festival. If you live in New York, you know that doesn't work for New Yorkers. They're suckers for convenience and the location had to be in New York City and easy to get to, which is why we wanted to be on Randall's Island ... [All Points West] was branded as a New York City festival, but it was in Liberty State Park in New Jersey. It wasn't geographically far away, but mentally for a New Yorker it was still New Jersey -- it might as well be in Toronto at that point.

There's no way of knowing if that particular quote was responsible for AEG's re-entry into the NYC festival market, or if the company had merely observed from afar the success of Governors Ball and decided to give it another go simply based on the impressive metrics, but last September, it was reported that AEG was "quietly talking [to city officials] about putting on a music festival at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park next June."

They were back.

Or they were trying to come back, at least, with an eye on returning for real in June 2016. Of course, Founders already had an event scheduled for that particular month: Governors Ball had always been held in June, and the 2016 installment was set to take place during the weekend of 6/3-5. The Daily News first reported the AEG story on 9/30/15, saying:

AEG has already started recruiting acts and has a date in mind -- two weeks after Governors Ball, possibly draining headliners from the city's only major three-day music festival, run by one of the last independent promotion companies in the music industry, sources say.

It's possible that Founders representatives were those "sources" -- the sympathetic reference to "one of the last independent promotion companies in the music industry" certainly suggests as much -- but who knows? Last week, Wolowitz spoke again to Billboard, saying he'd first heard rumors of AEG's plans about a year ago, and then was told of it "formally" last April, while at Coachella. Still, it was another five months till the story broke. And two weeks after that, on October 15, 2015, Founders loudly launched a petition to protect its own festival by asking the city to reject AEG's proposal, saying:

As reported in the Daily News and multiple industry news outlets, AEG is lobbying the Mayor's Office and other city agencies for approval of a major festival in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens two weeks after Governors Ball. The timing of this proposed event is an aggressive, greedy attempt by AEG to push a small independent company of born and bred New Yorkers out of business and out of the market.

First, Madison Square Garden asked the city for permission to host a "major outdoor music festival" in Flushing Meadows from 6/24-26 -- which would have been one week after the proposed AEG festival. Then, Founders itself applied to host a festival in Flushing Meadows from 9/30-10/2. (MSG and Founders aren't officially affiliated with one another, but the strategy behind MSG's involvement here will be explained in due time.) In mid December, it was revealed that AEG was unable to secure the permits necessary to stage its event during the month of June.

Four weeks later, the second boom was lowered.

Did MSG sincerely hope to stage a festival at Flushing Meadows in 2016? Did Founders? I have my doubts. I think both companies knew that by flooding the city with permit applications, it would lead to uproar among Queens residents, and the borough would have no choice but to hold off on approving any such proposals. Whatever the promoters' intentions, though, that was indeed the end result: a quagmire that forced the city to reject all 2016 concert applications for Flushing Meadows.

Said Queens Borough President Melinda Katz: "Events of any scale that enhance our borough are encouraged. The use of public parks, however, needs to be publicly vetted and coordinated under an official city policy, because the absence of one renders the entire process unfair. The merits -- or lack thereof -- of any existing or future individual application cannot be fairly considered in the void of policy and public participation, which are paramount."

Within hours of the news that its Queens proposal had been rejected, AEG announced that its NYC festival was still a go, with a couple minor adjustments, clarifications, and confirmations:

• Instead of Flushing Meadows, it would be held at Randall's Island.

• Instead of June 17-19, it would be held from July 22-24.

• Instead of All Points West or Coachella East or whatever other regionally unspecific name they might have chosen for the thing, it would be called Panorama.

The details of those applications, though, remain a total mystery to just about everyone. Consider this: While AEG, MSG, and Founders submitted their Flushing Meadows applications last fall, AEG reportedly submitted a separate application for a Randall's Island event on 1/4 -- a week before the decision was made. Per The New York Times:

People briefed on the negotiations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private details, said AEG's rivals were not aware that a Randall's Island date was in play.

Why did that date fall in late July while the Flushing Meadows proposal requested a weekend in the middle of June? Perhaps it was a function of the permit-application process or the park's availability. Perhaps it was related to exclusivity windows and non-compete clauses in existing contracts. Perhaps it was merely done to build a buffer between Panorama and Governors Ball, to give Panorama the appearance of a distinct identity, to make the festival more attractive to the same customer base that was now being asked to schlep to Randall's Island twice in the same summer.

"I get it, they were out of options," Founders' Wolowitz, told Billboard. "When the city said 'no' to Queens, [AEG] had no choice but to come to Randall's Island. I'm assuming they're kind of disappointed, too, because they look kind of silly in a way, that they have to do the same kind of festival as GovBall, seven weeks later, same site, contemporary bands. It's just going to be the same thing to the ticket buyer."

It's really not the same thing, though. And if AEG is disappointed, it is likely not because it's afraid of looking silly about doing the same thing as Governors Ball, but because its thing isn't "the same" enough -- because it's doing it seven weeks later than Governors Ball, rather than two weeks later or two weeks earlier or the exact same weekend.

See, late July is a terrible time to hold a three-day music festival in New York City. It's a terrible time to be outdoors at all in New York City. Many residents abandon the city entirely during July weekends; they go to the Hamptons or the Rockaways or the Jersey Shore or Cape Cod or anyplace else one might find water and sand and bathing suits. New York City is rather pleasant in mid-June, and it is absolutely disgusting in late July. If you live here, you can attest to that yourself; if not, you can take it from me -- or, if you prefer, listen to Trip Advisor:

[June] is the best time to be in the city, without doubt, [usually offering] less humidity and temps between 50-80 degrees, though June occasionally sees a 90-degree day. An occasional humidity-soaked heatwave can strike, but it usually feels nice the first time around.

July, meanwhile?

Hot, humid, sticky, sometimes oppressive. And that's outside, never mind the subways. Temps range from 70-95 and can get north of 100 occasionally, but highs are usually in the mid to upper 80s. Anticipate 20-degree temperature spikes in the subways. It's rather disgusting down there, and the heat brings out the worst subway odors. Don't underestimate the concept of humidity: It can make a warm day feel much hotter ... Bring an umbrella and anticipate torrential downpours.

Which of those scenarios sounds preferable for an outdoor music festival on an island in the middle of the East River?

"But it's an island," you say. "Where better to spend a steamy summer weekend?"

You, my friend, have apparently never been to Randall's Island. See, contrary to Wolowitz's assertion, Randall's Island is not exactly "easy to get to." It's bordered by Manhattan to the west, the Bronx to the north, and Queens to the east: yes, geographically speaking, the center of New York City, but practically speaking, a real fucking headache to access. Look at this:

To get to Randall's Island via public transportation, you have to hop a subway to Harlem, where you can grab the M35 bus on the corner of 125th and Lexington. Or you can take the subway to 34th Street, then walk a quarter of the width of Manhattan to the FDR drive, where you can hop on a ferry (they arrive/depart every 20 or so minutes). And there's no camping or lodging on Randall's Island, so a three-day festival isn't just three days of standing in a muddy field for 10 straight hours in 90-degree heat with occasional "torrential downpours"; it's also six trips on the bus or ferry, and six subway rides to and from those hubs.

Getting shut out of June was a big loss for AEG. Getting shut out of Flushing Meadows was a bigger one.

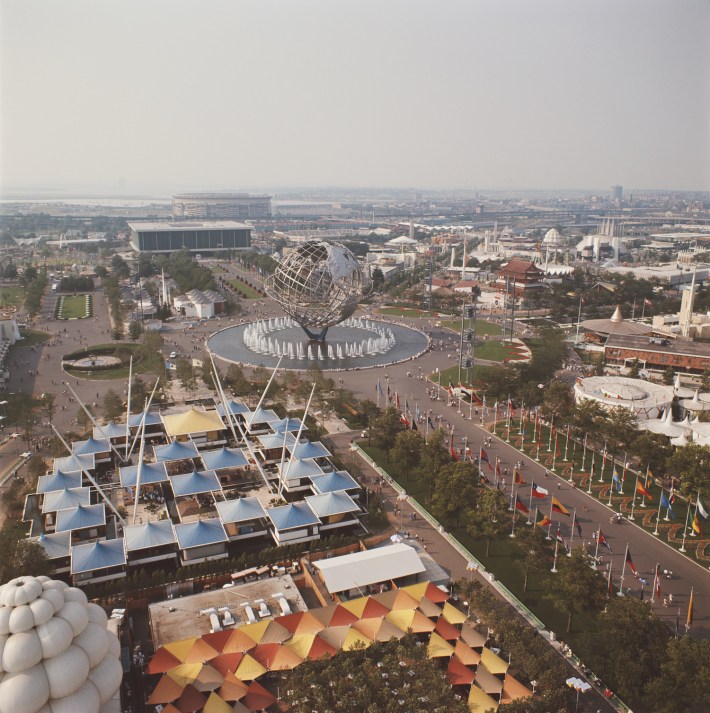

That whole sentence hinges on the word "probably," which is a bit of misdirection: Liberty State Park is indeed one of the only green oases that could meet AEG's other criteria, but it is definitely not the only one. There is also Randall's Island. And then, there is Flushing Meadows.

But not all land is created equal, and there's almost no standard by which Randall's Island might be considered superior to Flushing Meadows. Beyond the disparities in size (Flushing Meadows' 898 acres are more than twice as many as those offered by Randall's Island), there's the question of access: Compared to Randall's Island, Flushing Meadows is an absolute breeze to get to: The 7 train goes there directly; so does the Long Island Railroad. It's eight miles from JFK Airport, three miles from LaGuardia Airport. There are "countless hotels" in the immediate vicinity.

If Randall's Island has the edge on Flushing Meadows in any way, it is this: Randall's Island has been hosting festivals forever. When Lollapalooza was still a touring entity, it made regular stops at Randall's Island starting in 1994. Randall's Island is not residential, and therefore, has no community to displace or enrage. The Parks department can basically do whatever the hell they want there.

Flushing Meadows, on the other hand, is the neighborhood park for hundreds of thousands of Queens residents and it hasn't ever been rented out by a for-profit company for a charged-admission event. But unlike Central and Prospect parks, there's at least a chance you could get a festival approved there. The place was built for festivals. Literally! It was created to host the 1939 World's Fair, and even today is best known as the location of the 1964 World's Fair. Plus it's home to the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, where the US Open is held every year, and it's right next to Citi Field, the 42,000-capacity Major League Baseball stadium where the Mets play their home games.

So why is it only now that promoters are showing so much interest in Flushing Meadows?

First off, we have to consider the rapid growth of Queens itself. Once an undernourished afterthought in the massive shadows of Manhattan and Brooklyn, Queens has become "the hottest borough in New York City," according to Business Insider. It was named the #1 travel destination in America on Lonely Planet's Best In The US 2015 list. Its tourism numbers have grown at double-digit rates in recent years, showing percentage growth that's 50 percent higher than Brooklyn and 200 percent higher than Manhattan during the same time frame. Furthermore, the borough is much more densely populated now than it was even five years ago -- when Governors Ball launched -- and its northwest neighborhoods are almost unrecognizable relative to what they looked like at the turn of the millennium. And many of Queens' new residents are precisely the types of young, high-income people who might attend a gigantic three-day music festival. As the Daily News wrote last September, citing newly released median-rent data for the respective boroughs:

"Queens is officially the new Brooklyn."

There's something else too, though. If you follow regional politics and/or happen to be a David Bowie fan, you're probably aware that New York City has a relatively new-ish mayor these days: After 12 years with Michael Bloomberg at the wheel, Bill de Blasio was sworn into office on 1/1/14 (coincidentally the same year AEG reportedly started "engaging the community").

What are the differences between Bloomberg and de Blasio? Plenty, but the crucial distinction here is this one: Bloomberg is the seventh-richest person in the world, and he allegedly shelled out $268 million self-financing his three mayoral campaigns. De Blasio, on the other hand, relies heavily on contributions -- and his contributors expect returns on their investments. As Politico wrote, in a September 2015 story titled "The Transactional Mayor Returns":

City Hall is open for business. After the 12-year mayoralty of billionaire Mike Bloomberg, whose wealth afforded him level of insulation from campaign donors, a more transactional style of politics has taken hold through an organization Mayor Bill de Blasio set up to promote his policy agenda.

Wolowitz told Billboard that he believed Panorama washed up on Randall's Island because, "[AEG] had all the industry awaiting them to launch this new festival in Queens, so they had no choice but to save face, because otherwise they would have looked stupid and been out millions of dollars in these guarantees. They couldn't just swallow that loss."

There's probably some truth to that assessment, but it's a little myopic -- there's more to the story than just that. When the revamped Panorama plan was unveiled, it was covered by the local tabloids, whose interest in the music industry begins and ends on Page Six. But those guys love to talk politics. And there was plenty of politics to talk when it came to Panorama. The de Blasio-trolling New York Post got a quote from an unnamed "city official," who had this to say on the subjects of Panorama, AEG, and The Transactional Mayor:

When MSG and others also showed interest in Flushing Meadows and people started complaining about the borough's largest park possibly being shut for days, the Parks Department had to scramble to find another way to satisfy AEG because of its political connections.

And the plan remains to bring the Panorama festival to that location, too -- they're keeping the name because they see this as a temporary diversion. Said AEG Festival Producer Mark Shulman: "[AEG] remains committed to continue its work of the last two years with the park users, elected officials, park institutions, and communities surrounding Flushing Meadows-Corona Park to produce a world class event in Queens ... We look forward to continuing our discussions with NYC Parks to create an event to take place in Queens in the future."

Shulman's hope was echoed by a handful of local politicians -- among them City Councilwoman Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, who said: "I am disappointed that the event has moved to Randall's Island because our community has so much potential and so much to offer. However, I will continue to work towards bringing world-class events to Queens and improving parks for everyday visitors and district residents."

Of course, Ferreras-Copeland had publicly backed the proposal last December -- but not before AEG reportedly "promis[ed] to donate a portion of ticket sales to the newly formed Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Alliance," a privately funded conservancy launched by Ferreras-Copeland and de Blasio last November.

De Blasio didn't say anything about the move from Flushing Meadows to Randall's Island. Coincidentally, though, on the very same day Panorama was finally announced, the mayor reportedly found himself the recipient of a pretty nice little windfall via a lobbyist employed by AEG. Per The New York Times:

Harold M. Ickes, a longtime friend and mentor of Mayor Bill de Blasio, delivered about $13,000 in donations last week to the mayor's re-election campaign, on the day that one of his lobbying clients received the de Blasio administration's go-ahead to hold a lucrative music festival in New York City ... In all, Mr. Ickes, a longtime contributor to Mr. de Blasio, acted as the intermediary for $19,250 in donations in the four days leading up to the announcement that AEG could bring its festival to Randall's Island.

Furthermore, points out the Post:

AEG Live since 2014 has shelled out $150,000 to Ickes [to] help garner support to put on a major New York show. Ickes also served on de Blasio's transition team, so he played a role in the March 2014 hiring of Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver, who signs off on all park permits.

Here's another good tidbit from the Times:

Mr. Ickes [has] a lobbying firm based in Washington, and opened a New York branch after Mr. de Blasio was elected in 2013. AEG Live, which is owned by the Republican donor Philip F. Anschutz, hired Mr. Ickes in 2014; his firm lobbied several city officials and agencies on the company's behalf, disclosure records show.

And one more, just for context, from "The Transactional Mayor Returns":

[De Blasio's donors] include individuals and firms seeking approvals for their projects ... In some cases, donors gave money right before or after getting a city-granted benefit.

I'm just saying this now to clear my conscience, because I would really hate it if anyone's takeaway from this story was, "Well, I guess I should vote for whichever candidates have enough money to insulate themselves from special-interest groups and super PACs." Special-interest groups and super PACs might eventually bring the death of democracy, but oligarchs, demagogues, and monopolies will definitely kill democracy and half the population with it. (The other half will serve as human blood bags like Tom Hardy in the beginning of Fury Road.)

There's something else worth noting, too, just in the interest of keeping the scales balanced: AEG wasn't the only concert promoter to hire a lobbyist to grease the wheels at City Hall. The Times notes, "In the fall, Suri Kasirer, a lobbyist for Madison Square Garden, delivered about $56,000 in contributions, and James Capalino, who represents Founders, delivered $29,690." On that note: It was also "in the fall" that Founders launched its petition against Panorama, and "in the fall" that both Founders and MSG submitted applications to hold events at Flushing Meadows.

Final ancillary point and then I'll move on: As I said up top, AEG is not the biggest but the second-biggest concert promoter in the world. The biggest concert promoter in the world is Live Nation. Coincidentally, according to the Post, a woman called Melinda Katz was "among the Live Nation lobbyists who tried to block a City Council measure to regulate concert-ticket sales" from 2011-2012. If the name Melinda Katz name sounds familiar, it's because I mentioned her a while back in the context of her job today: She's the Queens borough president. Also, notes the Post:

Records show Live Nation [submitted] its own permit application to close part of [Flushing Meadows] park and host shows on June 11, August 6 and August 20.

Presumably those applications were rejected along with the ones from AEG, Founders, and MSG. But just in case you were worried about Live Nation's apparent absence from the Flushing Meadows mess, you can quit worrying. They're on it, and in it.

But I digress. Let's get back on topic.

If you believe Wolowitz, they did it "to save face, because otherwise they would have looked stupid and been out millions of dollars in these guarantees."

I love the bravado, but I'm not so sure about the analysis. I think the first year of Panorama was always going to be a loss-leader, no matter what happened. This wasn't a Vineland scenario, in which AEG was able to cut down the sapling before it had a chance to take root. Governors Ball had a five-year head start on branding. AEG had to get its foot in the door just to wedge the damn thing open. Even if AEG managed to get its Flushing Meadows application approved, it would have been difficult for Panorama to compete with Governors Ball, considering Governors Ball announced its lineup three days before the city delivered its verdict on AEG's applications. (As of today, AEG still hasn't announced the Panorama lineup, much less started selling tickets.)

Next year, though? I'd say there's about a 50-50 chance that Governors Ball doesn't even come back. Consider these two exchanges with Wolowitz from the 2014 Billboard interview:

New York is an important market for touring acts. What does the exclusivity clause for Governors Ball entail?

It really depends on how much the band is playing. If you're a brand new developing act playing the festival, oftentimes I'll waive the radius. But if you're an artist getting paid a fee commensurate to a major-level headliner, we'll demand a certain level of exclusivity.

Are you in the process of booking the 2015 Governors Ball?

Yeah, artists are routing 18 to 24 months in advance now. We're already booking some of the bigger acts and in negotiations with some others. The 2015 festival isn't for another year, but we're only seven months away from announcing its lineup.

So if artists are now routing for 2017, it stands to reason that they're presently in talks with both Founders and AEG for New York festival dates next summer, right? And if there are exclusivity clauses in place, it stands to reason that no major artist will be allowed to play both Governors Ball and Panorama. But here's the thing: Outside of Governors Ball, Founders really has nothing to offer those artists. AEG, on the other hand, could present massively incentivized package deals for any artist interested in playing Coachella. AEG could bundle a slot at Panorama with, for example, slots at Coachella in April, Hangout Fest in May, Firefly in June, FYF Fest in August, and/or Bumbershoot in September.

Wolowtiz revealed that AEG has already been employing such strong-arm tactics, and they cut into Governors Ball's 2016 options long before Panorama even existed. It was only a tiny bit, says Wolowitz, only a "couple of the bigger acts." But still:

A couple of the bigger acts that will be on their [2016] bill I lost out on, because I'm just sending an offer for GovBall when [AEG] were sending offers for Coachella, Panorama, Hangout, Firefly, FYF. They're putting their portfolio in a lot of these offers, so if an act is going to get an offer for a festival times five, or times three, the number on the offer is going to be much, much bigger than what I give. There were a couple of acts that went with AEG, which I totally understand, it was financially related. But, for the most part, I got the lineup I wanted.

Coachella, Panorama, Hangout, Firefly, FYF ... That's just a small sample of AEG's portfolio; it also books 22 other festivals across the country. It's not just festivals, either -- AEG runs facilities around the world, and if it's able to establish a festival beachhead in New York City and one or two other markets, it could eventually dictate domestic tour itineraries for almost every major artist. It's slowly on its way! Last week, the company released this statement, crowing about its 2015 accomplishments:

Overall, AEG Facilities' venues accounted for 35 percent of all tickets sold in the top 20 arenas and 27 percent of all tickets sold in the top 100, based on concert and show tickets sales in 2015, with 22 AEG Facilities-affiliated arenas ranking in the top 100 worldwide. In total, AEG Facilities accounted for more than 10 million tickets sold in 2015, accumulated from arenas across company-affiliated venues located on five continents.

One of those facilities is Brooklyn's Barclays Center, which opened in 2012. AEG doesn't own Barclays -- they just manage the venue's operations -- although in late 2014, AEG was in talks to buy a controlling interest in the arena. That deal didn't happen, but AEG remains an integral part of Barclays' operations, and Barclays remains at war with Manhattan's Madison Square Garden for New York City bookings. Notes BisNow:

In [2013], the Barclays Center sold more concert tickets than any other US music venue ... [In 2014] Madison Square Garden edged out Barclays to sell the most tickets of any American arena (793,395 to 723,616, according to Pollstar); Barclays ranked No. 6 worldwide.

It's obvious why MSG might view Founders as a well-placed ally, and why MSG might submit a proposal for a Flushing Meadows festival, even if nobody at MSG actually has the slightest bit of interest in throwing such a festival. MSG is fighting off AEG on numerous fronts -- because AEG is in a position to severely throttle MSG's concert revenue, as well as its prolonged relevance.

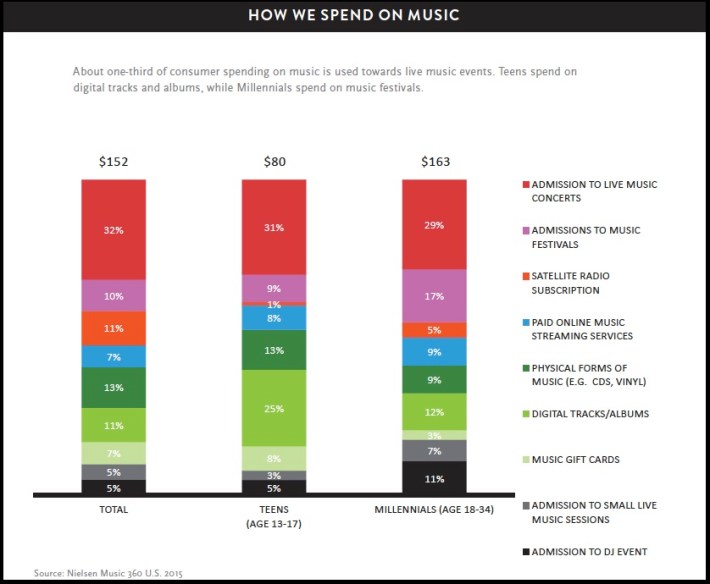

And it's not just MSG! A couple weeks ago, I wrote a story about the 2015 Nielsen Music Report: a 29-page document that presented a tremendous amount of data regarding America's consumption of music. The story I wrote focused primarily on recorded music -- because that's Nielsen's primary focus, too -- so I excluded any mention of their "How We Spend On Music" chart, which took a broader look at the ways in which we, um, spend on music.

This data was extrapolated from a survey of 500,000 Americans responding to the following question: "In a typical year about how much money do you spend on the following entertainment activities?"

As you can see, "Admission to live music concerts" accounts for the highest percentage of our music spending, and "Admission to music festivals" accounts for the second-highest percentage of millennials' music spending, and millennials spend more on music than any other demographic. Basically, AEG is making a hard play to own the most lucrative segments of the market. And I don't think they're reluctantly going through with a compromised Panorama in 2016 to save face or ensure at least some return on ill-advised guarantees signed months before they knew their fate in Queens. I think they're doing it because they know they have to pay some money of their own before they can claim ownership of everyone else's.

That's pretty hard to quantify, but historically, consolidation in the music industry hasn't been a net positive for the music-listening public.

For example, when radio was deregulated via the Telecommunications Act Of 1996: "An FCC study found that the Act had led to a drastic decline in the number of radio station owners, even as the actual number of commercial stations in the United States had increased. This decline in owners and increase in stations has reportedly had the effect of radio homogenization, where programming has become similar across formats."

Or you might consider the consolidation of major labels: From the '70s until 1998, you had the Big Six: Sony Music, Warner Music Group, BMG Entertainment, Polygram, MCA, and EMI Group. Then, in 1998, the Big Six became the Big Five; then in 2004, the Big Five Became the Big Four; then in 2012, the Big Four became the Big Three: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group. Between 1988 and 1998 the Big Six reportedly accounted for 77.4 percent of the entire recorded-music market, while as of 2012, the Big Three owned 88.5 percent of that market.

Prior to the final act of consolidation -- a merger between EMI and Universal -- the Future Of Music Coalition wrote an engaging polemic urging American and European antitrust regulators to reject such a merger. The piece ultimately compelled the Federal Trade Commission and the European Commission to do precisely nothing, and the merger went through smoothly. But even four years later, the essay lays out a pretty good argument against any sort of music-industry consolidation, on behalf of artists and fans:

Musicians have historically had very little leverage or bargaining power in the marketplace. If this merger is allowed, UMG would be in a strong position to influence artist compensation on emerging digital services and thereby perpetuate artists' lack of leverage. And we're not just talking musicians signed to majors. Independent artists and labels would ultimately be subject to the terms set forth by the two giant record labels -- especially because, unlike the majors, independents lack the bargaining power to negotiate for equity stakes and other alternative forms of compensation.

And that's what will happen here, too, if AEG manages to force out Governors Ball and reroute more artists through AEG facilities and events: It will homogenize music even further, and give artists less leverage and fewer revenue opportunities than previously existed.

But how will it affect you? Well, let's face it: It probably won't affect you at all, honestly, because you won't realize that it's happening or that it happened; it will just happen and you won't notice, because that's how these things go.

Discussing the ways in which AEG dropped the ball on Panorama 2016, Wolowitz said:

It's embarrassing for them, they've been promising this big festival in Queens with these huge artists and a new option for ticket buyers in New York, and they're just dropping another festival on Randall's that's going to be just like GovBall. They can say it's not going to be, but what's going to be the difference? They're going to have a prettier art installation than we are? A different taco truck?

Again, I love hearing that sort of brash attitude from anyone, especially someone representing New York City, and even more especially someone representing an independent voice in an increasingly corporatized field. But I wonder if he hears what he's saying. Basically, Panorama and Governors Ball will be more or less the same thing to the ticket buyer, on a superficial level. So what then is Governors Ball's competitive advantage? Better lobbyists? More suited to navigating the New York City Parks Department's labyrinthine applications process, and playing community boards against city officials? Because Founders certainly doesn't have more money than AEG, and we all agree that "a prettier art installation" and/or "a different taco truck" will be inconsequential to the consumer. There are so many unsteady variables that could spell doom for Governors Ball: e.g., if Governors Ball were shunted to July in 2017, while Panorama were granted a June date on Randall's Island. Or if the powers-that-be were eventually to allow Panorama to stage an event at Flushing Meadows. Or if AEG were able to successfully entice more than "a couple of the bigger acts" to sign on with Panorama instead of Governors Ball.

It's a little eerie, in retrospect, thinking about Vineland and All Points West and Governors Ball and Panorama, and the ways in which these battles have been fought in the press, especially when re-reading the language employed by each. Look at these quotes:

Vineland: "Dead."

AEG: "All Points West is an experiment that just didn't work."

That language ... I mean, you've got two different people somehow saying both the exact same thing and the exact opposite thing. "Dead" is dead -- the end. "An experiment that just didn't work" is a stop along the way. When an experiment fails, the people conducting that experiment learn what they can from the mistakes they made, adjust the variables to account for their new knowledge, and try again -- if they can afford to do so, and if the potential reward can justify their expenditures.

Here's another set of quotes to consider:

AEG: "All Points West is an experiment that just didn't work."

Governors Ball: "[We] cracked the code for putting on a successful contemporary music festival in the New York City market."

AEG: "It's very hard to get New Yorkers to cross that river."

Governors Ball: "[All Points West] was branded as a New York City festival, but it was in Liberty State Park in New Jersey. It wasn't geographically far away, but mentally for a New Yorker it was still New Jersey -- it might as well be in Toronto at that point."

Here you've got two people, totally unrelated to one another, saying things a year apart from one another, and yet it sounds like it could be dialogue from a movie.

One more:

Vineland: "That particular part of the country got too popular too fast; there are too many festivals in close proximity."

Governors Ball: "The timing of this proposed event is an aggressive, greedy attempt by AEG to push a small independent company of born and bred New Yorkers out of business and out of the market."

Two people, six years apart, saying the exact same thing about the exact same opponent: Goldenvoice. AEG Live. The Anschutz Entertainment Group. The Anschutz Corporation.

AEG.

They've tried it before. And if the cycle continues on its course, the next language will sound a little something like this:

Governors Ball: "Dead."

It may be dead already. I hope it's not, but I don't know. I know AEG kills things, because I've seen things get killed by AEG. It's the way of the world! The big fish eat the little ones. In order for them to grow, something else has to die. And if they miss their target, if the experiment falls short of expectations, don't worry. They can run another experiment in a few years. And they will. They've got the time, the money, and the incentive. They'll be back.