Jenny Lewis was the first musician who taught me that I didn’t have to be a bummer or a badass in order to be taken seriously, that feelings are valuable bits of insights that shouldn’t be immediately shoved down a garbage disposal. She was the first woman who taught me to be kind to myself; to know that being guarded is OK, but hardened is not. I first heard Rabbit Fur Coat -- which turned 10 yesterday -- when I was in middle school. My best friend’s big sister passed it on to us, asserting that the album was important to listen to because, “She’s in Rilo Kiley.” That qualifier meant nothing to me, because I hadn’t heard Rilo Kiley. The only indie music I listened to was made by men, and I only started listening to that stuff once I’d exhausted my craving for noisy Hot Topic-branded goth music. I loved Bright Eyes and Death Cab For Cutie, and I got into the Shins after watching Garden State one too many times. I didn’t want to be like Natalie Portman in that movie, but I wanted to be liked like Natalie Portman in that movie, if that makes any sense. I wanted to be one of the guys but I didn’t want to look like one of the guys or be considered "quirky," "waifish," or "whimsical." When you're first growing into yourself, it's hard to feel like your personality isn't tied to a "type," that it's not something you fabricate.

There are many women who came of age at the same time as I did who will cite Jenny Lewis as a beacon, a blinding light that illustrated what strength looks and sounds like when it's delicately delivered. She taught us about nuance, about being hundreds of different versions of yourself in a single song. If you were to pick any one line from Lewis' extensive career as a songwriter, the one that always stands alone, that defined her from then on, it would be from "Pictures Of Success," off Rilo Kiley's debut album: "I'm a modern girl, but I fold in half so easily." At the time Rilo Kiley put out their first LP, music critics were still able to use a descriptor like “breathy, pouty little girl” to explain away her voice without being completely eviscerated for it. Twitter didn’t exist back then, but I’m reluctantly inclined to cut them some slack because it’s true: Lewis sounded like a girl because she was a girl. She was a girl singing alongside male collaborators, rather than accessorizing them, in a scene largely dominated by men. (Which is, funnily enough, something that Lewis sings about on her latest album, 2014's Voyager). It's been said that when Rilo Kiley was first forming, Lewis wasn't even supposed to be the lead vocalist, which is almost laughable since she came to define that band. In 2006, though, Lewis wasn't the monstrous presence that she is now. It's charming to watch David Letterman speculate over who "Jenny Lewis" was nearly 10 years ago, when she made her first-ever Late Show appearance.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

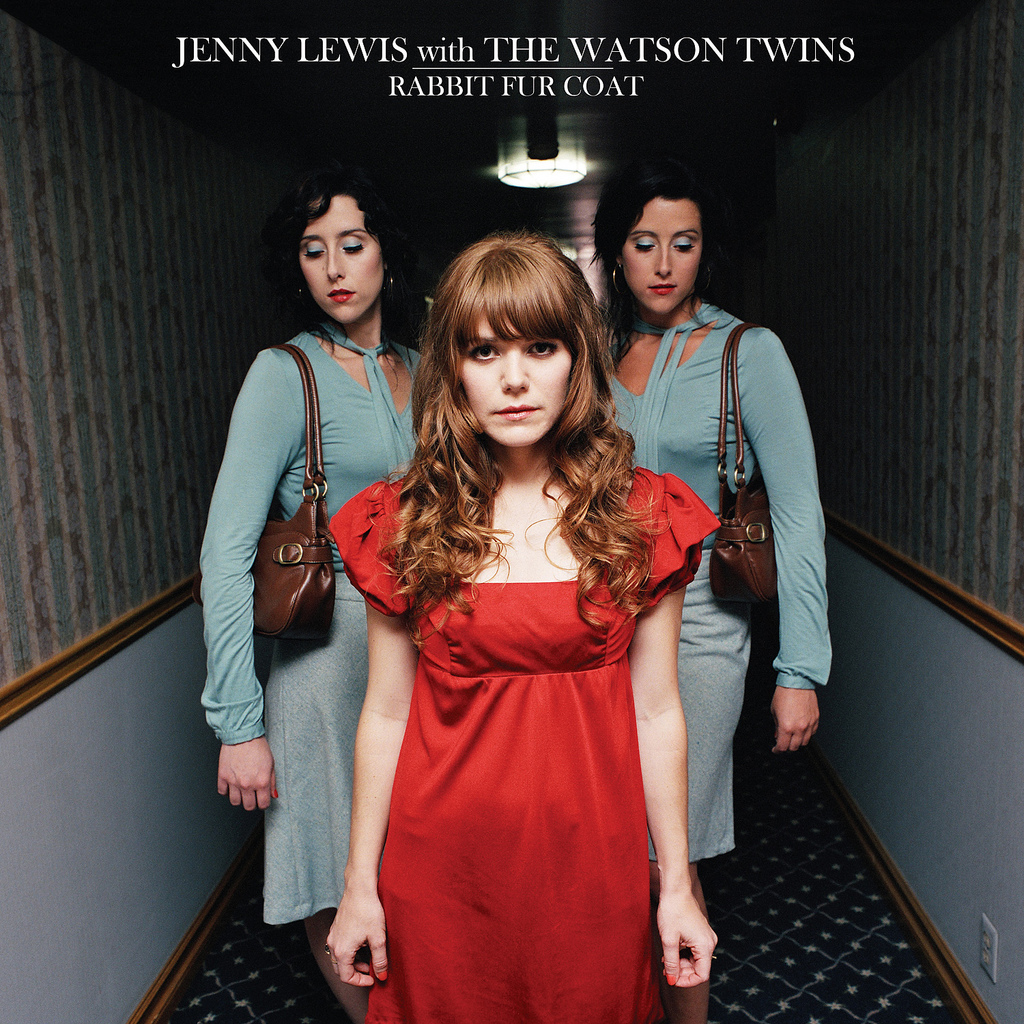

In order to make her first solo album, Lewis enlisted Maroon 5’s bassist Mickey Madden as well as Leigh and Chandra Watson, Southern-born, LA-based twins with an affinity for gospel harmonies and multi-chord arrangements. They were an apt choice for the collection of songs Lewis wrote on her own. Rabbit Fur Coat is not an indie rock album, and with the exception of one song, it bears little resemblance to the types of songs that Lewis wrote with Rilo Kiley. Rabbit Fur Coat is sort of a country album, it’s sort of a blues album, and a tribute to gospel. In a lot of ways, it’s a fictionalized creation of what Lewis -- who was born in Las Vegas and has lived in LA for most of her professional life -- might want her Southern narrative to sound like. This was her storytelling project. The album’s interlude is “Run Devil Run,” a song that could’ve been pulled from a Smithsonian blues archive and invokes the fear of God before Lewis’ songwriting really exposes itself. There is an intense spirituality in Rabbit Fur Coat that surfaces every so often throughout, as if to remind you that it is, in fact, kind of a country album. Americana, at least. Rabbit Fur Coat was recorded to analog tape, and even in 2006 you could tell. It sounded weathered, worn-down, and worthy of comparison to something that "once was."

The religious footnotes found throughout Rabbit Fur Coat weren’t necessarily intentional, and Lewis spoke to them a bit in an interview with NPR’s All Songs Considered around the time the album came out. There are the obvious references to the Devil, to God (or a lack thereof in the case of “The Charging Sky” or "Born Secular"), and then there are small lyrical moments that are at once grand, fantastical, Southern turns-of-phrase and still reminiscent of an earlier Lewis. On the second-to-last track, “It Wasn’t Me,” Lewis denounces spirituality entirely: “I've gone and quit my worshipping/ Of the false gods and golden sins/ Cause we've made love in the Tower Of Babel and it fell down.” These Biblical references might feel heavy, and they’re easy moments to get stuck on for those who were wedded to Rio Kiley’s asymmetrical lyricism and Lewis’ wry contemporary references. But what these moments do is recontextualize Lewis’ image within a vast landscape and make room for her to assume a role in a greater narrative. With Rabbit Fur Coat she was no longer the frontperson in a band; she was taking up her image a new incarnation in a long line of American songwriters before her.She hasn’t abandoned that post since, and no one’s usurped her.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

It’s important to note that the early to mid 2000s was a period in music that brought new, young life to traditional forms. Popular independent music mined the work of legends to create a breed of folk music that would mimic and collaborate with the greats. Bright Eyes’ I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning builds itself up around harmonies by none other than bluegrass great Emmylou Harris. That album is a meditation on a lot of things, but it’s mostly a reflection on life in New York, assisted by a voice that recalls some rural nowhere far from the city. As a kid who grew up in a city, listening to albums like that or Rabbit Fur Coat allowed me to experience time travel. Here we both were, rooted in a dirty, urban present, longing for something so-called simple and far-off; a country-ish kind of life where your overwhelming existential depression can be explained away by a parable. "So my mom, she brushes her hair/ And my dad's still growing Bob Dylan's beard/ I'll share with my friends a couple of beers in the Orlando streets/ In the belly of the beast," Lewis sings on "The Charging Sky."

That yearning might’ve presented itself as disingenuous to anyone who didn’t really exist within similar confines. But living in a city, spending your existence surrounded by bodies and minimal natural beauty, lends itself to a particular kind of longing. Rabbit Fur Coat finds Lewis reaching far outside of her confines. On this album she’s not the singer in an indie rock band; she’s an acoustic guitar-wielding songwriter who can hold her own alongside the greats. It’s easy to criticize this as posturing, especially in a landscape very concerned with creating stark barriers between personal revelation and fiction. But I have always thought of Lewis as someone who can create great narrative works that somehow still pose a means through which to self-reflect. Her revelations are huge, but they’re often burrowed beneath small plot lines. Lewis explained that the album was in part written as a collection of fictional narratives containing characters that shared her likeness, but only to a certain extent. The title track is at best a story of cyclical, familial poverty, and at worst a confounding riddle, one that I still try to parse a decade since I first heard it. In either case, Lewis’ voice makes itself as small as possible, morphing into that tiny quaver that counters the confident mastery heard in some of the album's bigger songs.

In a sense, Rabbit Fur Coat presented us with several different visions of the kind of songwriter Lewis would become. Songs like “Run Devil Run,” “Happy,” and its reprise, all indicated that she was leaning heavily into a gospel-inspired sound, which made a lot of sense since she wrote the album with the Watson Twins’ participation in mind. Their voices scaffold the album, appearing in harmonic bursts throughout. The short, simple songs serve a similar purpose; providing sparse, aimless musings that set the LP’s tone, as if to remind listeners that it’s a new experiment. Those repeating moments unfold on subsequent tracks. God returns to us in “Rise Up With Fists!!” in the form of a tempestuous lover, another man getting in Lewis' protagonist's way.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Rabbit Fur Coat’s centerpiece isn’t even one of Lewis’ original compositions. “Handle With Care” was originally released by the Traveling Wilburys, a band comprising George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, Tom Petty, and Bob Dylan. It’s a criminal lineup, one that’s not easily mimicked in a cover. But Lewis enlisted her friends, the verifiable holy trinity of indie at the time: Conor Oberst, Ben Gibbard, and M. Ward, to sing with her on it. The resulting cover is a joyous time capsule, a collection of voices who similarly came to define music in the mid-2000s.

The most common criticism of Rabbit Fur Coat is that Lewis likes to get wordy, that she overcompensates through verbiage and subverts the album’s soulful aesthetic by complicating it. It’s true: There are songs on Rabbit Fur Coat that stand out because they don’t necessarily fit into the narrative established by those early gospel interludes. But the best song on Rabbit Fur Coat, and arguably one of the best songs that Lewis has ever written, is easily the wordiest. Lewis herself has referred to it as a "mouthful," and hard song to sing live. It’s also the most honest songs on the album, a song that I learned from and will continue to learn from every time I listen to it.

“You Are What You Love” begins with the trill of an omnichord in sync with a piano, establishing a fantastical, Disney-fied motif that underscores Lewis’ earnestness. “You Are What You Love” is a song about nuance, it's about how unbelievably difficult it is to resign yourself to a relationship when you're constantly living in fear that you'll ruin it. It's a jumbled collection of messy feelings. I used to think it was a song about how the people you spend time with, the people you give yourself to, define you. "You are what you love, and not what loves you back." Those words empowered me. I listened to that song on repeat when my first hapless boyfriend ghosted me, and told myself that caring about him still made me weak, lesser. "To you I'm a symbol or a monument/ Your right of passage to fulfillment/ But I'm not yours for the taking." I thought it was a song about making yourself look big and strong on the outside, wary to let people into your life for fear that they'll realize you're "fraudulent, a thief at best/ A liar who paints a bullshit canvas." I thought that it was about being tougher and better than the people who you know will inevitably hurt you, about recognizing that we're always falling in love with idealized illusions of who the coveted "other" truly is.

Listening to "You Are What You Love" on repeat 10 years later taught me that Lewis' song isn't really a teachable moment. She wasn't pandering to my insecurities in the way that I thought she was. Instead it's just another confounding riddle, an outpouring of emotion that doesn't necessarily conclude in any sort of absolutes. Now when I listen to "You Are What You Love," I try not to analyze it. I just let every contradiction that Lewis lays out surround me, soaking in the myriad reasons why love hurts, love is a lie, love is really complicated. People are really complicated, and in that song, Lewis makes space for herself to be shitty and mean and cowardly, but also eager to please and vulnerable. Lewis wrote dozens of characters into a single album, letting all of her best and worst parts hang out at once, reminding me that none of us are truly all "stuck in our ways," despite asserting the opposite on "Rise Up With Fists!!" Lewis owned her sadness, honored it, in a way that wasn't exploitative or all-consuming. Rabbit Fur Coat proved to the music world that Lewis was dexterous, and she proved to me that I was, too.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]