Nu metal didn't have to suck. It wasn't an inevitability. It could've been something. The immediate foundational influences -- Faith No More, Rage Against The Machine, Downset, Helmet, Tool, Pantera's Vulgar Display Of Power -- are all pretty great. I should've thought to write an anniversary piece about Korn's self-titled debut when it turned 20 a year and a half ago, but I forgot about it. That's a good album. When that album came out, my friends and I were listening almost exclusively to punk rock and Wu-Tang, and we loved it. That album is a long way away from perfection, but it's intense and raw and formally daring. It established a new sound out of whole cloth, and it found ways for extreme, cathartic music to address things like self-doubt and emotional abuse. Our own Chris DeVille did write a piece celebrating the Deftones' Adrenaline when it turned 20 last year, and that's another case of what nu metal could've been: A dark, personal, atmospheric record that still still had a powerful heaviness behind it. The band moved on from that sound soon enough, and found more nuance, but the band's debut still stands on its own. And then there's Sepultura's Roots, a rare case of an established, beloved band finding a new sound and doing it about as well as it could possibly be done. I don't think it's a stretch to call it the best nu metal album of all time.

Here's what you need to know about Sepultura: They were a Brazilian band who spent the '80s building an audience by playing thrash metal as fast as possible and entering that whole Slayer/Testament conversation. Then, in 1993, they made Chaos A.D., a bold direction-change of an album that made them more popular than ever while alienating many of their older fans. On Chaos A.D., Sepultura slowed way down, lurching into this gargantuan monster-groove. They gave drummer Igor Cavalera a chance to really show his absurd combination of power and syncopated swing, and they gave Igor's brother, the band's frontman Max, a chance to unveil the full majesty of his throat-shredding roar. I loved Chaos A.D.. Loved the shit out of it. And Sepultura certainly could've ridden the sound of that album for at least a few more records; maybe they could've been headlining arenas on their own after a couple more of those. Instead, they turned left, and the left turn was Roots.

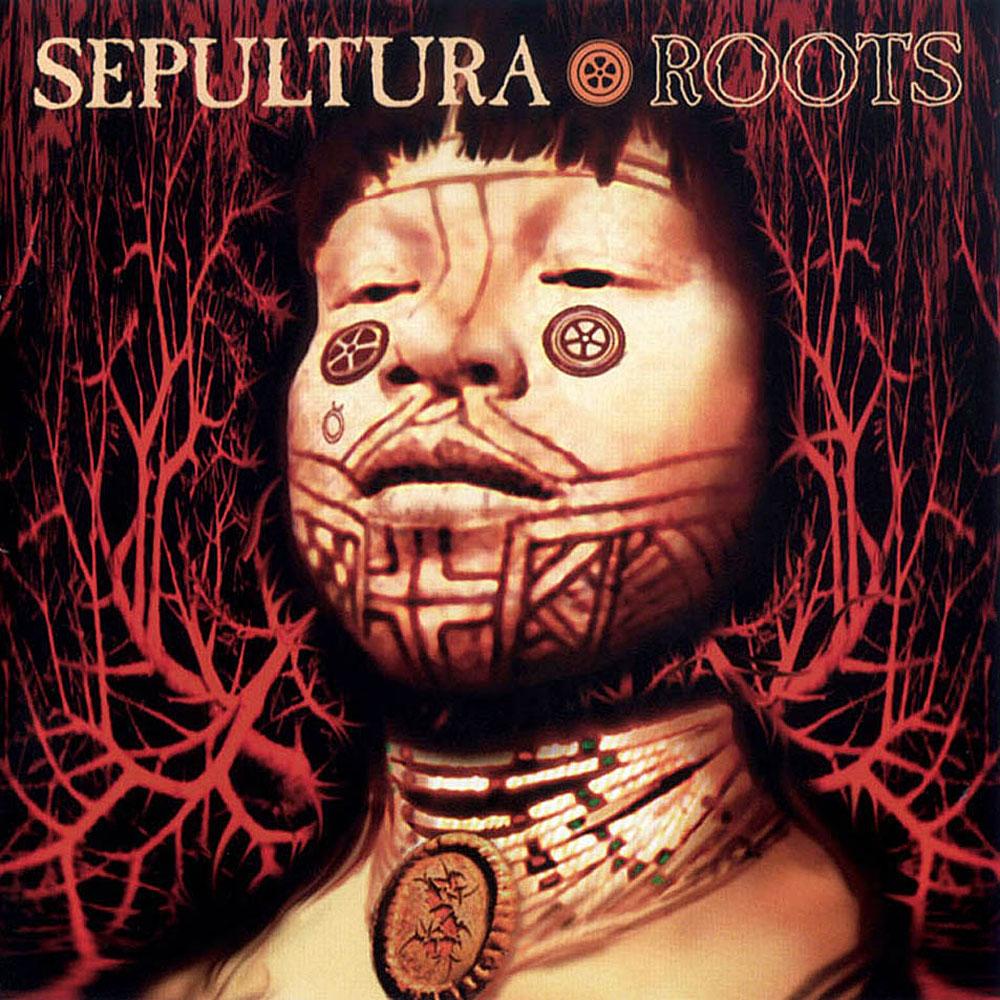

At the time of its release, the big story with Roots was that it represented Sepultura's embrace of their Brazilian culture, a trend that had started with a few songs on Chaos A.D. The lyrics went in heavy on Brazilian politics, sometimes in Portuguese, and one song featured a tribe of Xavante Indians. They weren't sampled, either; the band went out into the country and recorded with them. There's tribal percussion and chanting all over the album. The cover features an image of an indigenous woman that originally appeared on a Brazilian banknote. One video had members of the Gracie family, the martial arts experts who'd introduced Brazilian jiujitsu to the world and who'd helped to found the UFC. On that level, the album is a powerful statement. It's a band of third-world superstars looking deeply into their own culture and into the injustices that helped to form it. We don't get too many of those.

Listening to Roots today, though, that's not what jumps out first. Instead, what jumps out is that this is a nu metal album. The band produced it with Ross Robinson, the producer who more or less defined the sound of nu metal. He'd done Korn's debut, and he'd go on to work on the first Limp Bizkit album, a bunch of Slipknot records, and Vanilla Ice's attempted nu metal reinvention Hard To Swallow. (If you're looking for reasons not to hate Robinson, he also did At The Drive-In's Relationship Of Command, the Blood Brothers' ...Burn, Piano Island, Burn, and the Klaxons' Surfing The Void.) The sound of Roots -- guitars downtuned massively, bass so distorted that it sounds like angry whalesong, vocals so buried and growled that they barely sound human -- is pretty much exactly the sound of Korn's debut. The song "Lookaway" featured vocals from Faith No More's Mike Patton and Korn's Jonathan Davis, and it also had scratches from House Of Pain's DJ Lethal, who would go on to join Limp Bizkit.

If you read that last paragraph, muttered urgh, and closed the tab, I wouldn't blame you. But Roots took all those nu metal elements and turned them into something bruising and indelible. On Roots, Sepultura had an urgency to them that they didn't even have in their thrash days. Even for those of us who only know about life in Brazil through sensationalistic movies like City Of God or Elite Squad, Roots has power because it forces you to think about what life would be like in a violent and corrupt society like that one. It encapsulates the rage and fear and impotence that comes along with that level of absolute helplessness -- raging against the machine when you know full well that you can't stop it. To a small degree, that first Korn album did the same thing, but for personal demons rather than societal ones. This was, for a time, music that had things to say, and I'd argue that the genre first found a foothold because kids in bad situations heard things in it that they didn't hear elsewhere.

This could've been what nu metal was. Instead, things took a different turn. Fred Durst came along and made it a vehicle for his unbelievably halfassed rapping. Sharon Osbourne came along and used it as a vehicle for her cultural domination; she kept Ozzfest relevant just by piling these bands on the bill. The most terrifying high school jocks in American came along and used it as their vehicle to turn concerts into slugfests. Meanwhile, Max Cavalera left Sepultura and started Soulfly, a straight-up nu metal band, and never recorded anything nearly as powerful as Roots again. It made sense that he threw in with the genre completely. For a time, this stuff rivaled peak-era teenpop as the most popular music in America, all its lifeforce and vitality drained out. So in retrospect, Roots represents a moment of lost possibility, a fork in the cultural path. We took a look at that fork, and we went the wrong way.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]