There is only one aspect of Call The Doctor, Sleater-Kinney's second album, that's aged even remotely in the 20 years since its release: the fixation on tall, gawky, socially awkward New York rock frontmen in "I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone." That song, and the purpose and confidence it displayed, were what originally brought Sleater-Kinney to the attention of the rock critics whose endless praise helped get Sleater-Kinney out of the vans-and-basement-house-parties circuit. Its chorus still hits like grenade shrapnel. But when you listen to Corin Tucker's elemental howl, you have to wonder: Why would she want to be anyone's Joey Ramone or Thurston Moore? Given the choice, wouldn't any of us rather be your Corin Tucker? It's a question that the past 20 years have complicated, now that Ramone has died and Moore has revealed himself to be, at the very least, an asshole. But even leaving that stuff aside, there's a force and immediacy to what Tucker does on that song that easily equals anything those two guys ever did. "Pictures of me on your bedroom door! Invite you back after the show! I'm the queen of rock and roll!" It's still thrilling. Back in 1996, when Tucker and her band were complete unknowns, those were audacious statements. Listening to it now, it almost sounds like she's aiming too low.

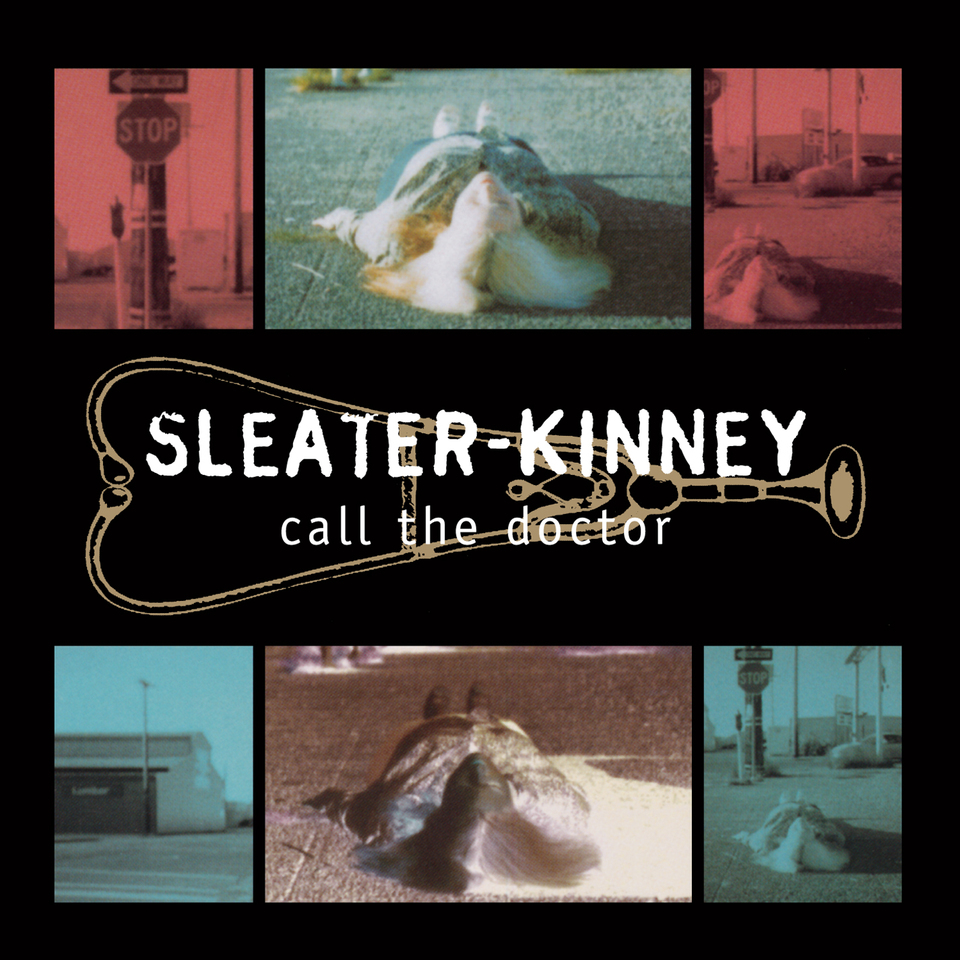

Call The Doctor wasn't Sleater-Kinney's debut, but in a lot of ways, it functioned as the trio's introduction. The band's self-titled album, recorded and released a year earlier, was a side-project situation. Both Tucker and Carrie Brownstein were in other bands -- Heavens To Betsy and Excuse 17, respectively -- and they recorded it in Australia, while on a sort of vacation. It's a strong enough album when judged on its own merits, but in the context of Sleater-Kinney's mighty discography, it sounds more like a set of rough demos. Call The Doctor was something else. It was the first thing that Brownstein and Tucker did when they decided they wanted Sleater-Kinney to be a full-time project, and it's the first one that they recorded with John Goodmanson, the producer who did most of their records and who best understood their sound. (If you ever want to get me riled up, feed me some drinks and ask me about what Dave Fridmann did to the band on The Woods.) More important than all that, though, it's the first album that really captured Sleater-Kinney's full fury. If you were so inclined, you could hear the band's entire career as the slow refinement of what Tucker did on Call The Doctor.

It's weird, in a post-Portlandia world, to hear people talk about Sleater-Kinney as Carrie Brownstein's band. Brownstein is an utterly badass presence onstage, of course, and she's vital to the band's sound. These days, they're a group of three equals, all of whom feed off of one another. But hearing Call The Doctor for the first time, it was clear that Tucker was the force powering this whole enterprise, at least early on. Her second "damn you!" on the intro of the breakneck "Little Mouth" might still be the single most vital moment in the band's entire career. As a band, Sleater-Kinney had precedents: The raw dynamics of Huggy Bear, the muted fury of Slant 6. But I'd never heard anyone who sounded even remotely like Tucker. She sounded like a trapped animal, or like an angel of retribution. There was so much need and strength and fear and anger in her voice. She held nothing back, and she sounded like she'd burst apart if she tried to keep any of this stuff inside.

But Call The Doctor wasn't just the band's feral, instinctive big bang. There was technique to it, too. The most immediate moments were the ones where Tucker sang about being a woman and feeling trapped. (The intro to the album-opening title track is still so vivid: "They want to socialize you / They want to purify you / They want to dignify and analyze and terrorize you!") But they could be subtle, too. "Good Things" and "My Stuff" are sad and slow and tender, and they're indications of the emotional places where this band would go soon enough. Tucker and Brownstein's guitar lines were already intricately intertwined, something that Goodmanson's mixing job -- one guitar in each speaker channel -- would highlight. And they were starting to figure out how to layer their voices over each other, to turn each song into a conversation.

It's incredible that Sleater-Kinney would get better after this album, that they'd push their more daring and innovative ideas further without losing the urgency that made Call The Doctor so special. Albums this fiery often tear bands apart, especially in that mid-'90s riot grrrl era, when bands so rarely lasted more than one album. Sleater-Kinney could've split apart, too. Instead, they leveled up. They wrote cleaner, sharper, more intricate songs. Immediately after recording the album, they jettisoned Lora Macfarlane, their just-fine Australian drummer. Soon enough, they replaced her with the great Janet Weiss and completed the picture.

Still, the raw force of Call The Doctor makes it a special album, even in a career like the one they've had. The band wrote the album in a few weeks and recorded it in five days, in the same studio where Nirvana and Jack Endino had recorded Bleach. They played in the same room, using minimal overdubs and keeping their best takes. It's a short, sharp, shock of an album, a trebly and desperate rush. Writing these 20th-anniversary columns, I like to spend time talking about an album's influence, about the effect that it had on other artists. I can't do that here. I don't think I've ever heard another band replicate that feeling. I don't know if I've heard another band even try.

The music critics of 1996, especially old-guard figures like Greil Marcus and Robert Christgau, deserve credit for hearing Call The Doctor and immediately knowing that it was something special. This was an album from a group of unknowns, released on a tiny label in the era before the internet could help music like that find its audience. And it still got glowing reviews; writers still treated it like the instant classic it was. Call The Doctor finished at #3 on The Village Voice's year-end Pazz & Jop critics' poll, only coming in behind Beck and the Fugees. Chainsaw Records couldn't print up copies fast enough, and the band ended up moving to the slightly larger Kill Rock Stars for their next album, a year later. That press attention wasn't always good for the band. A SPIN feature mentioned Tucker and Brownstein's relationship with one another before either one had come out to their parents. But the way critics immediately took to the album is a testament to its force, and that force endures. Sleater-Kinney would go on to do even greater things after Call The Doctor. But if they'd broken up the day after finishing it, their place in history would be assured.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]