For the most part, I didn't handle breaking news at my old job, so it fell upon one of the younger staff members, a very smart and funny man fresh out of college, to tackle the terrible news of Scott Weiland's untimely passing last December. He did a great job, though I was struck that he called Weiland and his band Stone Temple Pilots "iconic," and spoke of the singer strictly in glowing terms. I started talking with the the news editor, a fellow old, about how everyone ragged on Stone Temple Pilots back in the '90s, calling them alternative-rock carpetbaggers, and even if you liked them, you might be inclined to downplay your fandom in order to maintain your cool points. That is, you might do that if you'd recently decided to get into Sebadoh but still loved your alt-rock radio titans, even if you weren't sure you should. (The editor later pushed me to write about this topic. I'm glad she did.)

My younger friend mainly knew of Stone Temple Pilots as a great band. A great band with a troubled singer, sure, but a great band nonetheless. On a sad day, this gave me a small amount of solace. That's how, above all else, they should be remembered. Stone Temple Pilots were a great band, and one of their greatest albums, Tiny Music... Songs From The Vatican Gift Shop, turns 20 tomorrow.

When news of Weiland's passing hit, I tweeted "I loved STP back in the day, but being an insecure teenager felt weird about it because of Pavement/critics/'authenticity.' Different times." and went on to talk with some of my music writer friends about how unthinkable it would be today for a popular band to get crucified for being "inauthentic." There's multiple reasons this once-common concept now seems so alien, but I think the main five are:

1) As Brian Eno once said, nobody owns any particular sound or idea, and stealing from someone and then making their thing your thing is how art works. This idea is more commonly accepted than it once was. (Which is not to say cultural appropriation isn't a problem, but let's parse that line some other time.)

2) "Authenticity" is now basically a marketing tool, usually for overly earnest (and usually boring) singer-songwriter types that get a lot of NPR burn.

3) Admitting that you want to be popular and then writing pop songs is far preferable to bemoaning the spotlight while also chasing it.

4) If something sounds good or great, why not let yourself enjoy it?

5) That high horse will give you a nosebleed.

Though poptimism has its drawbacks (there's an entire nursery next to the bathwater), it has made for a kinder, more inclusive, less judgmental music culture. No one should ever be made to feel bad for liking whatever it is they like, and no artist should ever have to be judged on any terms except their own. Which is not to say a popular act shouldn't be assessed fairly and then called out for sucking, but at least make sure to say it sucks for the right reasons. (That said, I'm sure 19 years from now some bright young Stereogum staffer will talk about how Twenty One Pilots' Blurryface made them a music fan for life. Everything reoccurs.)

You guys might find enough examples to prove that I'm talking out of my ass, but one of the side-effects of modern "can I live" music culture is that fewer and fewer artists feel the need to prove they are for real, which they used to do by making the Cred Album. The Cred Album is when an artist -- usually a critical whipping boy or pop star seen as fun but lacking in depth or staying power, but sometimes a respected artist worried their success makes them suspect -- proves that critics were wrong about them and they have the record collection and cool producer to prove it. I had to think about it for a while, but the last Cred Album I can recall is Mumford & Sons' Wilder Mind, on which NARAS' favorite band ditched the banjo, hired a drummer, and became just another KROQ band. Before you ask, I just don't think that album Miley Cyrus made with the Flaming Lips counts. (Who even knows what she was thinking with that one.) I suppose an argument could be made for Lady Gaga's Born This Way, but let us not digress.

The '90s were a serious time for serious people, as all that peace and prosperity really had folks on edge. This was a time when the term "sellout" might still have meant something. (For young people unfamiliar with this term, here's a good summation.) So at some point, serious artists were expected to release Cred Albums to prove they were in it for the right reasons. From recording a caustic kiss-off with Steve Albini to stopping by MTV Unplugged to covering an unreleased Bob Dylan song, most major artists got around to eventually doing this sort of thing back then.

Right after Stone Temple Pilots' first single, "Sex Type Thing" hit, the San Diego band were accused of trying to ride the gravy train set in motion by Nirvana and Pearl Jam, and as they got more popular (and they were one of the biggest bands in the world for a while there), the backlash intensified. Rolling Stone basically chided their readers for naming them Band Of The Year in their Reader's Poll. Spin all but asked God to wipe them from the face of the planet. And then there was "Range Life." (While Scott Weiland was a man with many, many flaws, who should not be over-valorized simply because we loved his music, to his immense credit he never seemed to nurse a grudge about Pavement for years after this song was released, unlike a certain Grand Pumpkin.) So when Weiland, the DeLeo Brothers, Eric Kretz, and producer Brendan O'Brien decamped to Santa Barbara to record their third album (ah, the '90s, when money fell from the sky in the music industry), they had a lot to prove. So it's wildly perverse that their attempt to show they were credible musicians was making a hip-swiveling sex-bomb that reveled in camp. Didn't they want to be a grunge band? Say what you will about these guys, but Soundgarden and Pearl Jam would never risk looking this ridiculous, much less allow themselves to be seen in public having fun. This cheekiness came from a place of deep artistic conviction. (Now that I think about it, it's a damn shame Weiland never got to duet with Brandon Flowers, his closest heir. That shit would have been fabulous.)

On their 1992 debut Core, and their 1994 second album, Purple, Stone Temple Pilots presented themselves as Sabbath and Zeppelin-worshipping heshers, canny enough to update their lurch with a bit of college-rock verve. On Tiny Music, they showed how deep their classic rock affection went, pulling influences from the Beatles (most profoundly on the sublime ballad "Lady Picture Show"), T-Rex, Kiss, Slade, Cheap Trick, and a whole lot of David Bowie. They even made a bossa nova song, the lovely "And So I Know," a year before Beck did. Robert DeLeo and Kretz proved themselves one of the most flexible rhythms sections of their day, capable of slinky numbers like "Big Bang Baby" and swinging hard on "Trippin' In A Hole On A Paper Heart," and even the more traditional hard rock numbers had some mascara smear on them. One way to prove you're serious is to show that you know your shit seems to be the message here.

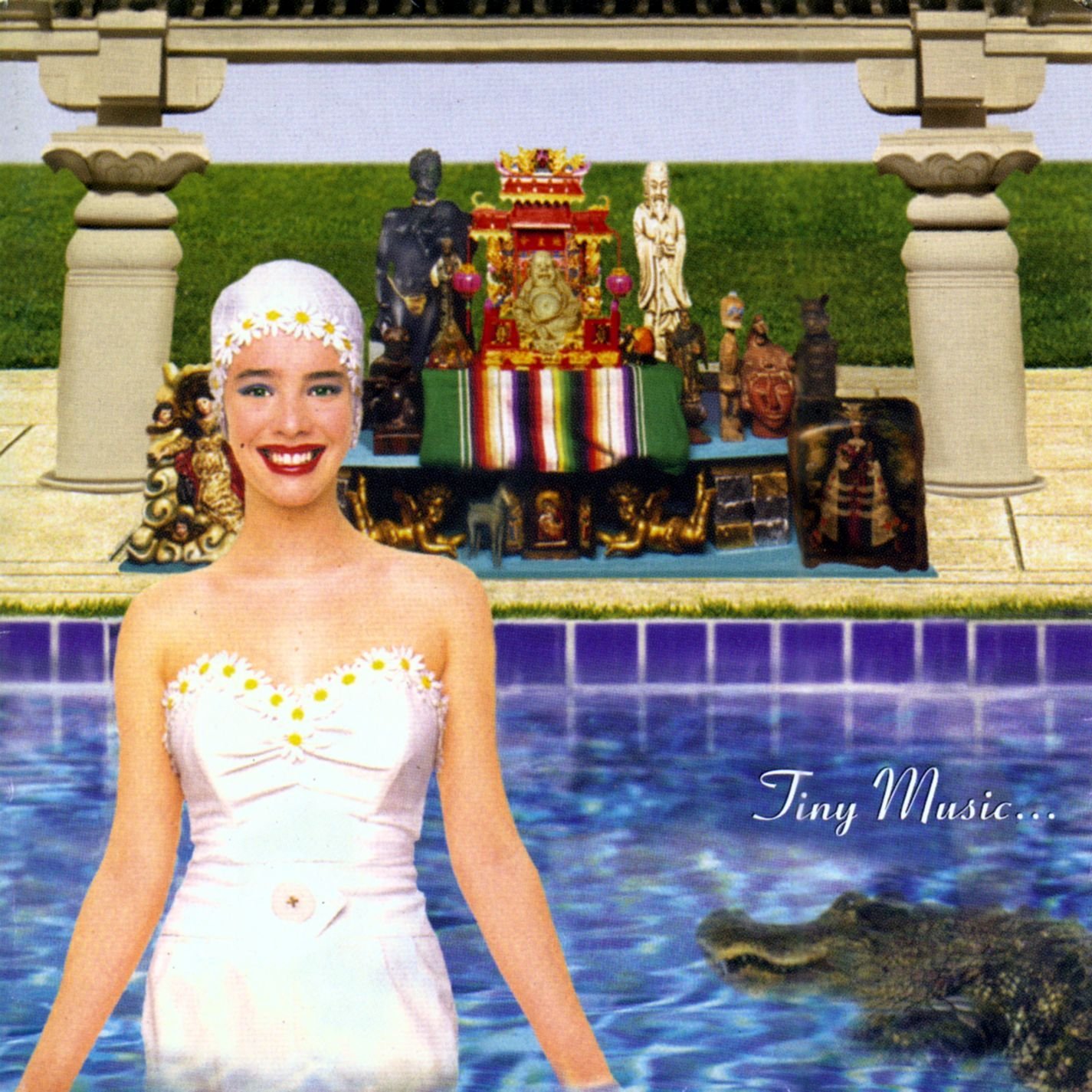

I don't want to overpraise this album, because it certainly has some elements of its time that haven't aged well: Both the title and having a jazzy instrumental called "Press Play" are textbook '90s "ha-ha irony," the cover art is garish, and though its overreach is charming, "Art School Girlfriend" feels like the band telling the listener, "See, we know who Andy Warhol and Lou Reed are." That said, the songs on Tiny Music were some of the most melodically rich Stone Temple Pilots would ever write, connecting the dots between arena rock and glam rock and grunge and synthesizing their influences into an approach that felt uniquely them.

The singles all did well, but Weiland's drug problems made touring difficult (though I loved the show I caught), and the album didn't sell as well as the previous two. The critical feedback was mixed, which was at least a step up from outright hostility. Spin wouldn't budge, but Rolling Stone grudgingly said nice things and put them on the cover. My most devout headbanger friend called the album "gay," which I think would have made Weiland happy, and by the time Bush, Live, and Creed starting clogging up the airways, Stone Temple Pilots didn't look so bad anymore. (And again, the reason those bands suck is because they didn't understand Nirvana and Pearl Jam well enough to rip them off properly.) Though it's not quite their best album (Purple has the most classic songs, though all five of the albums they recorded before their first split were at least solid -- yes, even Shangri-la Dee Da), it's the one that true STP-heads point to when making the case that these guys were true pop craftsmen in an era too uptight to appreciate such a thing.

By the time Weiland went in to make Tiny Music, he'd already been arrested for possession and gone to rehab a bunch, and ghoulish types wondered aloud whether it would be him or Layne Staley who followed next in Shannon Hoon's shoes. But while his band were classic rockers, Weiland was a thoroughly '90s frontman in the Stipe/Cobain mold, obsessed with irony and poking holes in his own image and determined to interrogate both the entertainment industry and his role within it. "Big Bang Baby" is about how empty fame is, and why that's not always such a bad thing. Weiland mentions his own death several times throughout, which made revisiting the album in the weeks after his passing rough. He was aware that people thought he was going to join the rock martyr club; on "Tumble In The Rough" he tells us he's not looking for a new way to die, on the ballad "Adhesive" he wonders if he'd "sell more records if I'm dead." On "Trippin' On A Hole In A Paper Heart" he assures us he's not dead and he's not for sale, and we should both hold him closer and let him be.

Weiland's struggles with addiction and mental health (he was very open about his bipolar disorder), will probably always cast a shadow over the music he made. Even as the credibility concerns have faded, it's hard not to wonder what he could have come up with if he kept it together, and not gotten distracted by his demons or pandered to what he thought his fans wanted as the hits started drying up. Maybe Stone Temple Pilots could have made something even bolder than Tiny Music. But that's not what happened. Like the rest of us, they did what they were capable of doing in the time that they had and no more.

It's hard not to be morbid when thinking of Weiland these days, but let's remember that Stone Temple Pilots were usually a blast, and Weiland prided himself on doing his best to appear like he didn't give a shit what you said. The guy who sang on Tiny Music knew what we thought of him, but he didn't care. "How could I ever die," he tells us with a wink and a sneer. "I'm a rock star, baby. I'm going to live forever." Maybe he'll be right.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]