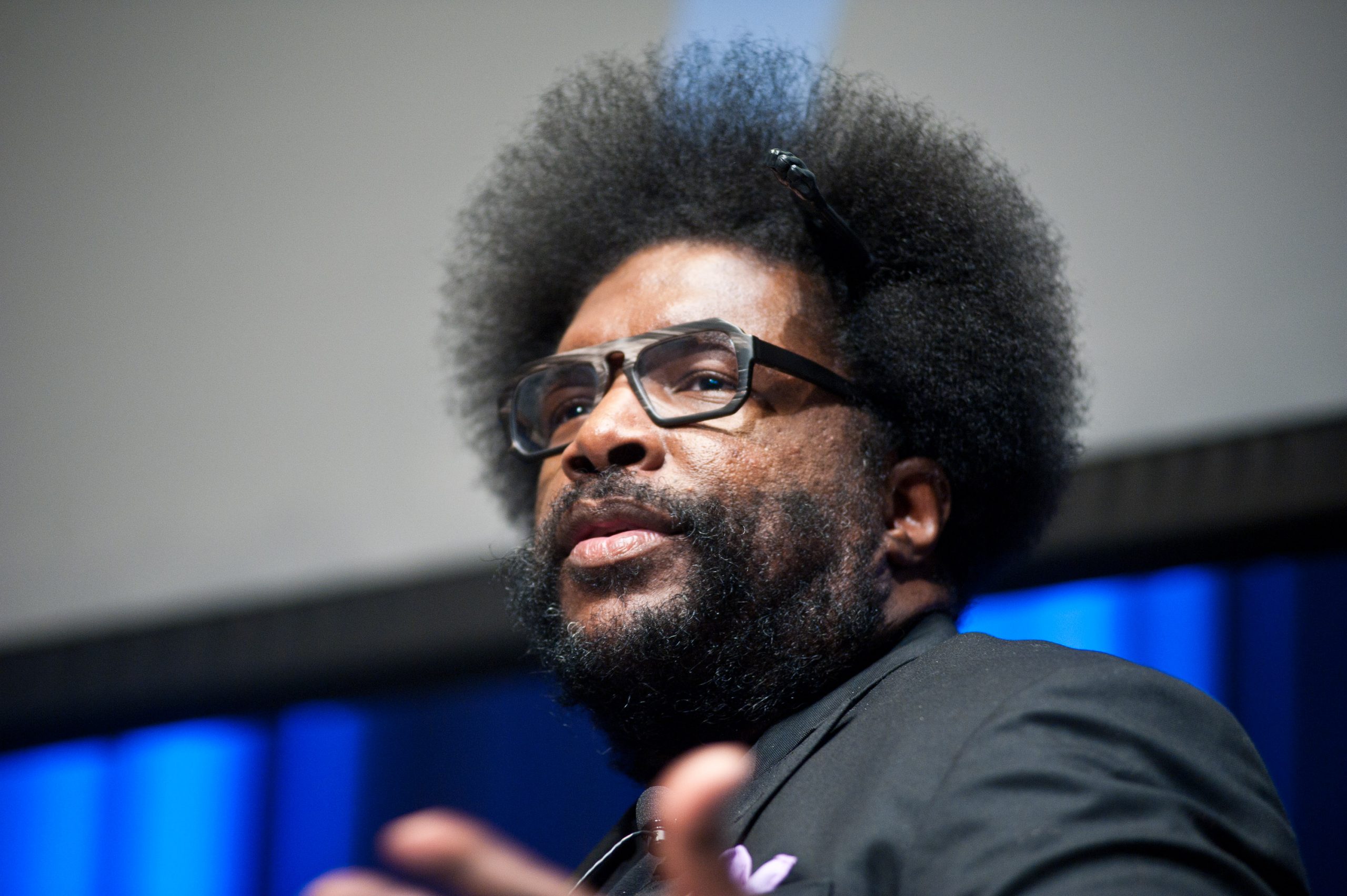

Questlove is a huge Prince fan. He's already paid tribute to the late icon in several ways -- social media mourning, playing Prince songs at a DJ set while playing Finding Nemo in the background -- and now he's written a lengthy piece for Rolling Stone that does double duty as a eulogy and a personal essay, discussing his own relationship with Prince's music in addition to the Purple One's legacy and influence on the world.

Questlove's devotion to Prince began in 1982, when he was 11 years old and "newly in charge of my own record-buying habits." His born-again Christian parents discovered and destroyed four different copies of 1999 that he managed to smuggle into the house, so he had to become craftier: "I found a friend to make me cassettes of Prince's albums. At home, I loosened the heads of my drums and hid the contraband in there. I listened when I was practicing, playing something totally different on the drums so that my parents wouldn't know what I was actually hearing." And from then on, "Prince was in my ears and he was in my head. Starting then, I patterned everything in my life after Prince. I had older half-brothers, but Prince -- unknown to me then, but not unseen or unheard, thanks to magazines, TV, radio, and my secret stash -- was a guide to me in every way."

Questlove then delves into the actual music on 1999, discussing various aspects including its James Brown influence and drum programming. "In the wake of his death, as we all try to come unstunned, everyone is talking about his genius. That's understandable," he writes. "But most of the discussion is general. I like to think about the specifics. I like to think of the way he innovated even early on, the way he turned away from the traditional blueprint of funk and soul music." And despite the fact that "Prince's relationship to hip-hop has been the subject of much scrutiny, and more than a little mockery," Questo declares that "at heart, he was more hip-hop than anyone."

"Later on, I got into the music business myself," Questlove then writes. "I got to meet Prince several times. I roller-skated with him. I went to parties that he threw. But I always felt like a fan, never a peer." He then relates one particular story of meeting Prince at Paisley Park, when Prince had already become a Jehovah's Witness and didn't curse. "I slipped up," Questlove recalls. "It wasn't anything too major. I think I said 'shit.' Prince had a curse jar; every curse cost a dollar. 'But you're rich,' he said. 'Put in $20.' 'Hey,' I said. 'You taught me how to curse when I was little.'"

Questlove concludes with this touching passage:

I don't know. There's so much we all don't know. This is what I do know: Much of my motivation for waking up at 5 a.m. to work — and sometimes going to bed at 5 a.m. after work — came from him. Whenever it seemed like too steep a climb, I reminded myself that Prince did it, so I had to also. It was the only way to achieve that level of greatness (which was, of course, impossible, but that's aspirational thinking for ya). For the last twenty years, whenever I was up at five in the morning, I knew that Prince was up too, somewhere, in a sense sharing a workspace with me. For the last few days, 5 a.m. has felt different. It's just a lonely hour now, a cold time before the sun comes up.

Read the full piece here.