It's Weird '90s Week on Stereogum. All week long we're looking at the strangest musical moments and trends of the decade. Check out more here.

In February 1999, Garth Brooks held a press conference to announce some baffling news. The biggest-selling artist of the decade had signed with the San Diego Padres, who had offered him an invitation to attend spring training and try out for the major leagues. In lieu of salary, he was making a sizable donation to the Touch 'Em All Foundation, the questionably named children's charity that raises money for other children's charities. It seemed like an odd match: The Padres had won the NLDS the previous year, losing the World Series to the damn Yankees. They might have shed some foundation players during the offseason, but the team hardly seemed so desperate that they would need a pudgy everyman country singer to round out their roster.

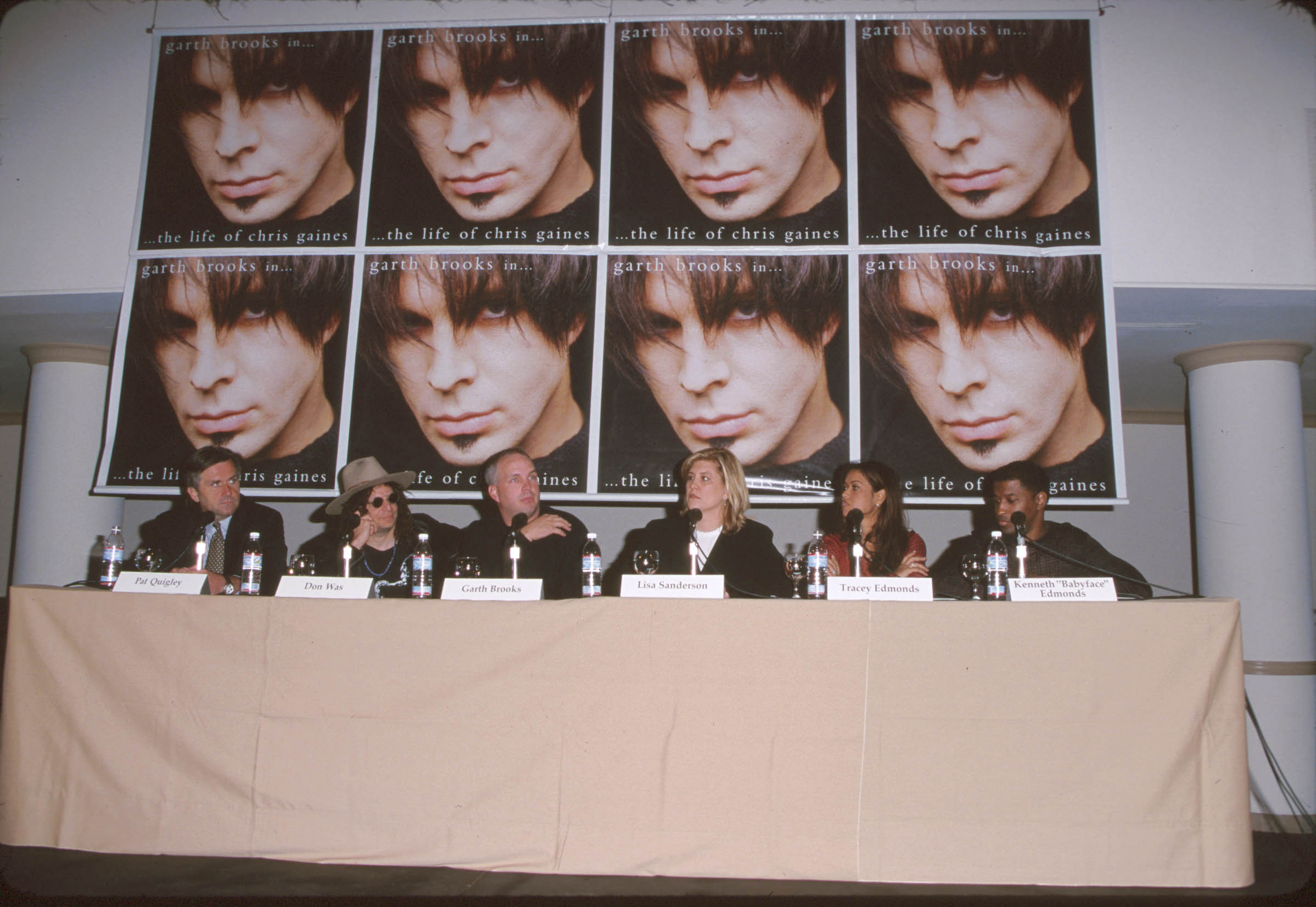

That announcement made Brooks' other news that day seem almost ho-hum: His next project would be a film called The Lamb (executive produced by Kenneth "Babyface" Edmonds), which would be preceded by a soundtrack and a "prelude" album introducing listeners to the main character, a fictional Aussie rock star named Chris Gaines. Also, he was working on a Christmas album. Even if he didn't make the Padres (and he didn't), Brooks was going to be pretty busy in the months leading up to Y2K.

San Diego went 74-88 that season and finished a lowly fourth in the NL West, but Brooks suffered an even more ignominious fate. His one album as Chris Gaines turned out to be a complete head scratcher, one of the weirdest moves of the decade by a major recording artist. It would confound critics, alienate fans, and effectively derail his career. Of course, nowadays selling 2 million copies of anything earns you messianic status within the industry, but it was a huge flop for an artist with more than 95 million sales under his big belt buckle. After 2001's Scarecrow, he would retreat to Las Vegas for most of the 21st century, a flagship sent to the scrapyard. In some ways, the Chris Gaines debacle would mark the end of the CD boom and usher in a new digital era when such hubris was unthinkable.

So who was Chris Gaines, and why does he loom over the 1990s like the specter of death? Brooks concocted him as a sort of rock 'n' roll Citizen Kane, a mysterious figure cloaked in shadow, already dead in the opening scene of The Lamb and glimpsed only in flashbacks. The film's protagonist would be a diehard fan convinced that Gaines had been murdered, possibly for the sins of his fans. Penning the script was Jeb Stuart, the guy who wrote two of the best action movies ever made: Die Hard and The Fugitive. It must have sounded promising at the time, especially for a rock star who had outsold the Beatles and Elvis Presley but couldn't buy a crossover hit.

As early as 1991, when he released a bombastic cover of Billy Joel's already bombastic "Shameless," Brooks began signaling his ambition to escape the strictures of the Nashville machine. Each new album re-calibrated the balance of twang and rock, and while he might have been dismissed by country purists and derided by alt-country insurgents, few artists in any tradition seemed to have as much fun as Brooks did locating the infinite possibilities in these decades-old genres. For that reason, most of his '90s albums hold up surprisingly well. Songs like "The Thunder Rolls" and "The Beaches Of Cheyenne" portrayed him as a natural storyteller, while "Friends In Low Places" proved he could lead America in a honky-tonk sing-along. But it's the ballads that are best, revealing a vocalist who redeemed even ridiculous material (Fresh Horses closer "Ireland") with the precision and sensitivity of a mid-century crooner.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

As the decade and his career progressed, however, Brooks conflated creative license with commercial ambition, which turned later albums like 1995's Fresh Horses and 1997's Sevens into cheeseball spectacle. Success began to take a heavy toll. In interviews he persistently referred to himself in the third person, as though split in two, and his ambition to outsell his heroes curdled into something like bloodlust. In 1998, he released The Limited Series, a box set collecting his albums with new bonus tracks. It sold 5 million copies. Even more successful was Double Live, a naked cashgrab featuring multiple album covers and no audience noise. It sold 16 million. Repackaging the same old songs to the same old fans not only seemed like an insult to the idea of disposable income, but also suggested Brooks was at a creative crossroads.

To an artist running out of ideas, perhaps the notion of absorbing his unwieldy public persona, with all its expectations and restrictions, into the identity of a made-up rock star became appealing enough that Brooks overlooked just how bizarre the idea might appear to outsiders. Bruce Feiler, who penned one of the first books on Brooks, 1998's Dreaming Out Loud, theorized to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "He's showing his controlled schizophrenia to the world. It's exactly what I was talking about in the book, that there are two Garths... In the early '90s, when I first started writing that he had a dark side and was fascinated by early death, it was considered so out there. Look at the lyrics to 'The Dance,' to 'If Tomorrow Never Comes' or 'The Beaches Of Cheyenne.' Now it's basically coming true. Here's Chris Gaines, a guy who gets killed off and is resurrected by Garth. This is the inner recesses of Garth's imagination, and a lot of fans are scared about it."

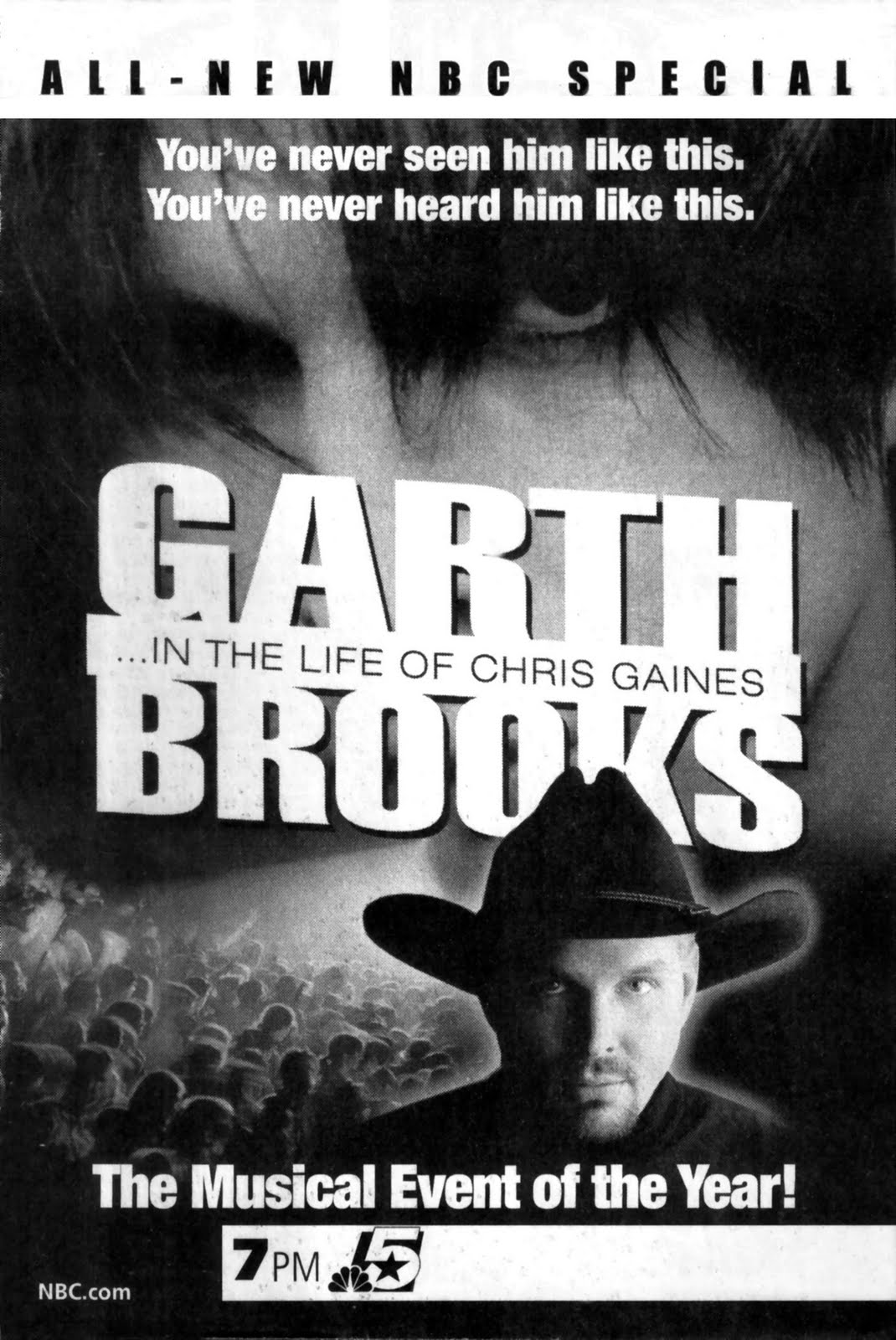

Schizophrenic or not, Brooks undertook the role with a method actor's determination. He slimmed down to fit into Gaines' leather pants, traded his cowboy hat for guyliner, grew a soul patch, and practiced his falsetto. He worked on his Aussie accent and even taped an NBC special and an episode of VH1's Behind The Music in full character. As a crowning touch, Brooks hosted Saturday Night Live with Gaines as his musical guest. As he told the Los Angeles Times: "We want people to go into the theater and know Chris Gaines and care about Chris Gaines... The thing I'd like to get across is how serious we are about this. There's the Rutles and there's Spinal Tap, and this is exactly the opposite."

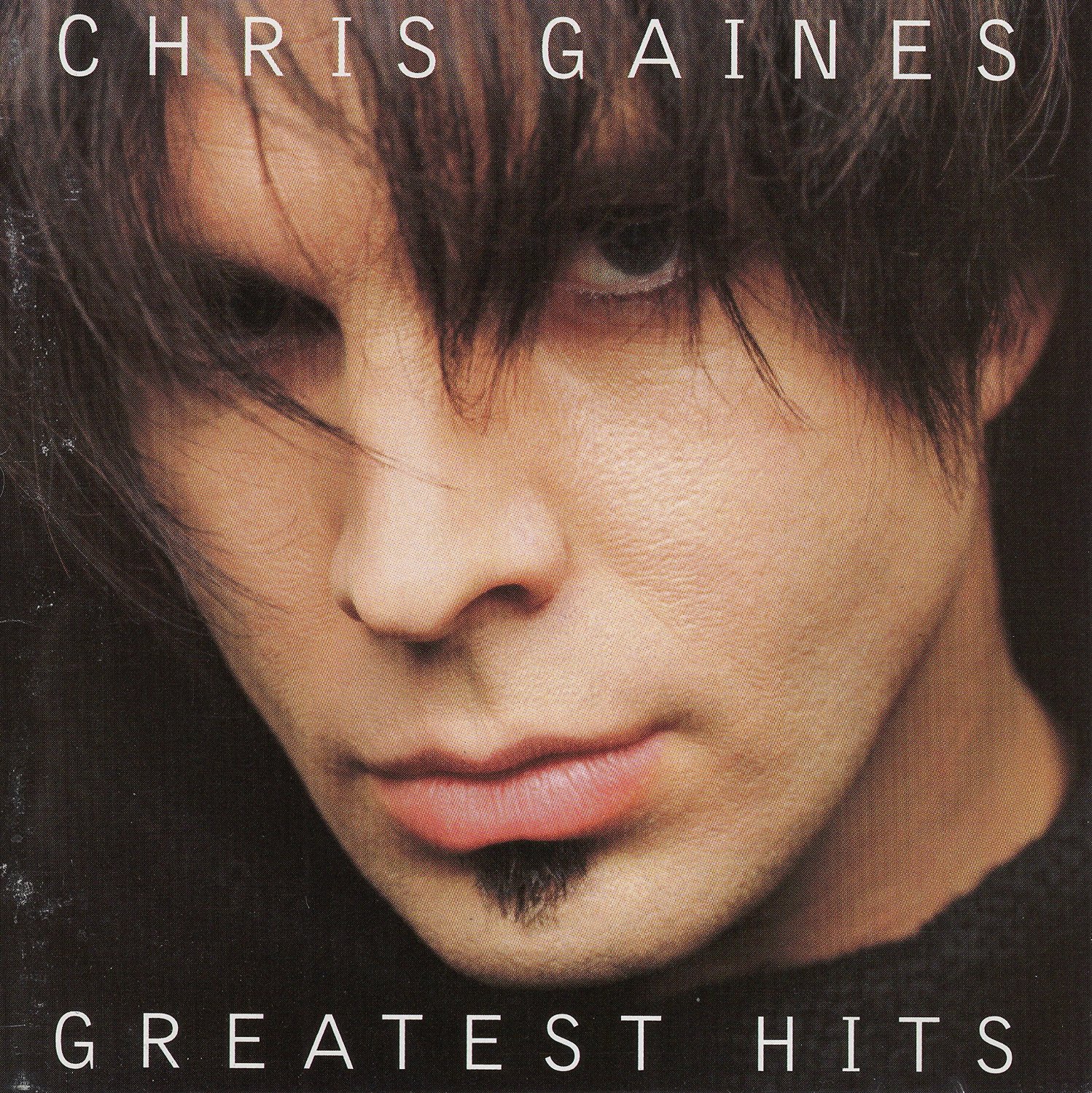

When he finally released that prelude album in September, his dedication to the concept proved astounding, a bit desperate even, and certainly discomfiting. Produced by Don Was (Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt, Barenaked Ladies), In The Life Of Chris Gaines is a bizarro-world greatest hits, gathering songs from fictional albums and showing the range of a successful artist who had been around long enough to try out different sounds. Gaines had a look and a back catalog, but neither seemed especially plausible. On the album cover he looked like a failed pick-up artist trying to launch a career in magic, and that soul patch looked silly even in 1999, when people still wore goatees in public. Listeners curious enough to flip through the CD booklet found fake photos and album covers documenting various stages in Gaines' career, but they were so strange and so ludicrous that they blurred the line between back story and outright parody. In what real or fantastical world would Fornucopia actually exist?

In The Life is far and away the worst entry in Brooks' catalog, but nearly 20 years later, it has accrued a bit of so-bad-it's-good magnetism. Musically, the album is all over the place, meandering from the sappy slow jam "Lost In You" to the rudimentary funk of "Snow In July" and revealing an artist with boundless ambition and absolutely no self-awareness. The nadir is the self-serious white-guy rap of "Right Now," as Garth-as-Gaines ponders a range of social ills then steers the song into a trainwreck with the Youngbloods' "Get Together." The highlight, on the other hand, is a melancholy ballad called "It Doesn't Matter To The Sun," which with a little pedal steel wouldn't sound out of place on a Garth album. (On a side note, former Eagle Don Henley covered the song last year at the Ryman when he previewed his first country album, Cass County. You can't make this stuff up.)

The album's most unforgivable sin, however, is its dullness: the bland conception of rock 'n' roll as a receptacle for vague angst, empty theatrics, and awkward innuendo. There's no rage here, no sense of abandon or confrontation, nothing motivating the music beyond some nebulous meta identity crisis. And that makes it an artifact of its time, an album that slots a little too neatly alongside the slick post-grunge rock of Creed's Human Clay and Nickelback's The State, both released in 1999. Neither of those acts influenced or were influenced by Chris Gaines, but all of them sound suspiciously similar in retrospect, as though Brooks was parodying something that barely existed at the time. But Creed and Nickelback sucked well into the 2000s, whereas In The Life can't be separated from the '90s. Garth-as-Gaines wallows in the nonsensical introspection that had come to define alt-rock, and he ratchets his self-absorption to choppily looped beats that sound less like Mellow Gold and more like "Lullaby" or Surfacing. Surely Shawn Mullins and Sarah McLachlan weren't the touchstones Brooks was aiming for...

Brooks may be the only person surprised that fans stayed away in droves. He and his label made a point of not promoting the record to country radio, instead concentrating on rock outlets already puzzled by the weird concept. The strategy failed spectacularly, and the film was quickly scrapped. Still, "Lost In You" managed to hit #5 on the pop charts, a Herculean feat in retrospect. Brooks might have cited Hank Williams's Luke The Drifter persona as a precedent, but country music has never been about the concept. Rather, the genre's guiding principle is precisely the opposite: If rock 'n' roll allows Bowie and Madonna and Prince and so many others to change personae from one song to the next, country music prizes what it perceives as real people playing real songs for real audiences, with no celebrity scrim real or perceived getting in the way. Even country concept albums let listeners know exactly what's going on; no one, in other words, really thinks The Red-Headed Stranger is trying to convince anyone that Willie Nelson is an actual cowboy murdering people out in the desert.

Perhaps the real reason for Chris Gaines' failure is that Brooks went too far and not far enough. He developed all the details, ridiculous as they were, but from the very beginning it was sold as a Garth Brooks project. Who in the 1990s could possibly shimmy out from under the heel of that enormous snakeskin boot? Would listeners have shrugged so hard if they didn't know it was Garth Brooks, if this Chris Gaines was an unknown import from Down Under? Would he have had a chance to live if there was some mystery to his identity? Would he have been a fascinating and larger-than-life character if he had been marketed virally, introduced via phantom web sites and leaked songs?

The words "viral" and "marketing" hadn't even been conjoined at that point in the digital era, but 1999 was proving to be a year for such elusiveness. Just months before the release of In The Life, a small movie starring nobody in particular crept into theaters, touted not as a fictional horror movie but as the edited tapes of three very real people who had set off in search of an American legend. Was The Blair Witch Project real? Was it a fiction? For a while no one really knew for sure. It wasn't just clever marketing, but a strategy that played into the film's subject matter and enlarged its world, to the extent that Chapter III Records released a companion album (featuring music by the Afghan Whigs, Skinny Puppy, and Bauhaus) and claimed the tracklist was taken from a mixtape found in the characters' abandoned car.

But the real reason Blair Witch worked so well was because it was fun to let ourselves pretend to be fooled by the marketing campaign, which heightened the scares. By presenting Chris Gaines as a Garth Brooks character, Brooks didn't let listeners make that decision or enjoy the confusion of bent reality. He simply told everybody to accept it. That strategy might have been an act of creative cowardice or celebrity hubris, prioritizing sales over concept. Or it might simply be a means of conceiving reality that was suddenly and irreparably made obsolete by the Internet. In a world haunted by the Blair Witch, Chris Gaines was an anachronism before he even sang a note.

So it's even weirder to think that Chris Gaines may actually have been ahead of his time in another respect. In the 21st century, the borders separating country, rock, and pop are arguably more porous than ever. Established pop artists sojourn to Nashville for a twangy album, and nobody bats an eye. In fact, Jewel, Sheryl Crow, Darius Rucker, Don Henley, and now Cyndi Lauper have all enjoyed late-career bumps thanks to their embrace of country. Meanwhile, Taylor Swift has moved from mainstream country to mainstream pop with a fluidity and grace altogether missing from the Chris Gaines project. Perhaps Brooks blazed that trail for her and other young artists to follow, but that's hard to argue. Swift's trajectory from Nashville to New York lacks any change in persona; she is never anyone other than the self she presents to us. She needs no alter ego.

Meanwhile, the ghost of Chris Gaines still haunts Garth Brooks 17 years later, hovering just out of sight at every show and deep in the mix of every album. At a press conference in March 2015 to promote a show in Buffalo, Brooks fielded questions about his doomed alter ego, and The Boot reported his response. "I love the music, and that's what it's all about," Brooks explained. "Would I love to do a second one? Sure. Would I ever drop that much weight again? I don't think I could." It's hard not to imagine him sounding a bit wistful, as though that route of escape has been closed off and he is now finally stuck being Garth Brooks.