It's Weird '90s Week on Stereogum. All week long we're looking at the strangest musical moments and trends of the decade. Check out more here.

"You have to understand, we are monks, not rock stars."

Those are the words of an unnamed representative of the Benedictine Monks Of Santo Domingo De Silos, widely quoted in an Associated Press article that ran in papers around the country. In 1994 the monks found themselves in the unusual position of having to shoo away the paparazzi and reassert certain distinctions that ought to have been obvious: In contrast to the fame, fortune, and often the hedonism associated with rock stars, Benedictine monks take a vow of poverty and stability, pledging to remain within their autonomous communities for the rest of their lives.

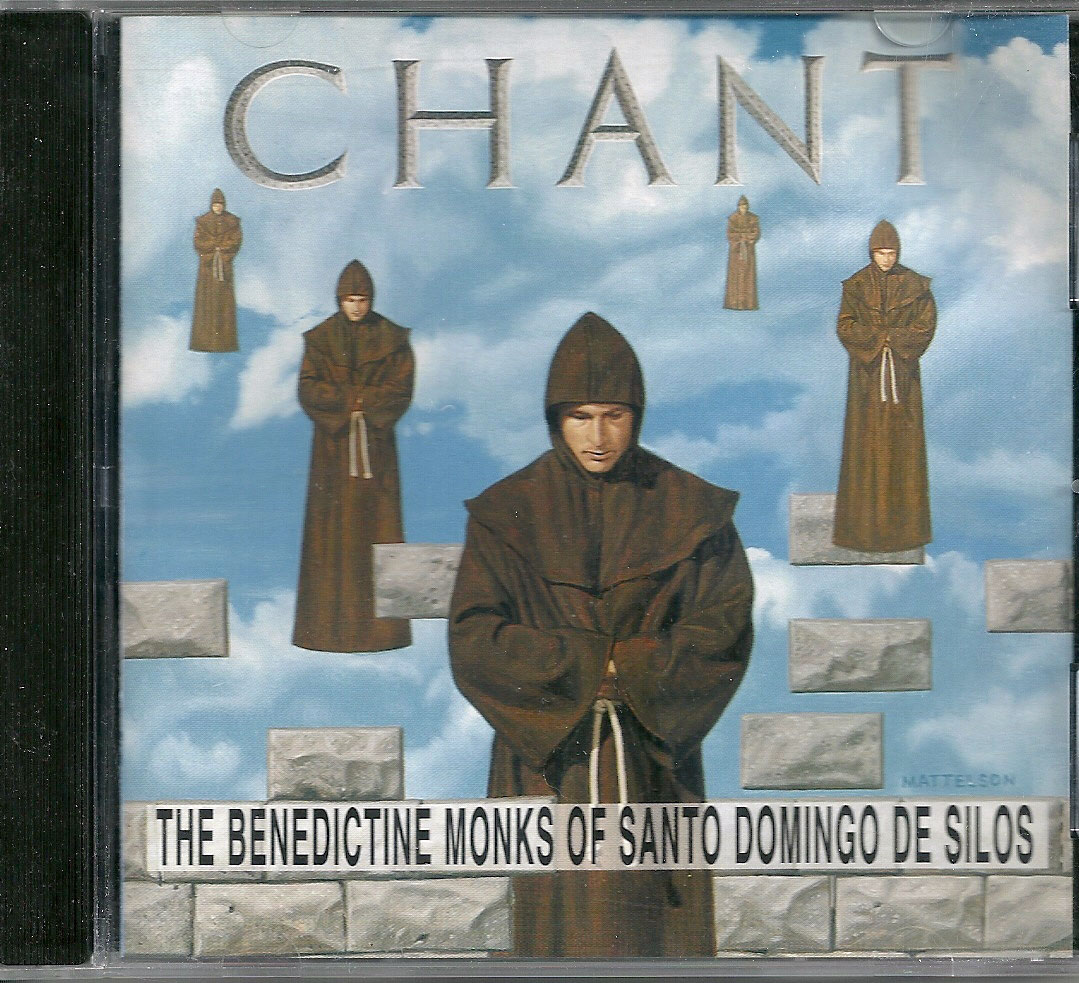

In 1994 the monks had a massive out-of-nowhere hit with their debut, simply titled Chant, a double-disc collection that collected recordings made at their monastery in remote Spain. The CD sold more than three million copies worldwide, and its cover -- a surrealistic image depicting monks floating in a Simpsons-blue sky -- became iconic among housewives, college kids, ravers, slackers, yuppies, hippies, alt-rockers, and New Agers. How did a centuries-old liturgical tradition become one of the most inexplicable pop crazes of the 1990s? No one is quite sure.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Gregorian chant -- better known as plainsong, plainchant, or evensong -- is about as unplugged as you can get. It's performed in a dead language, with absolutely no accompaniment save the rich reverberations off ancient chapel walls. Choirs of male voices construct harmonies unusual to modern ears, rising and falling with a communal rhythm to create a sound that is at once modest exotic, austere yet often sublime. Practiced for more than a millennium throughout Europe, the form is really, really old, although how old is up for debate. Actually, the term "Gregorian chant" is a misnomer: Early historians credited the standardization of certain musical and liturgical forms to Pope St. Gregory in the seventh century, but most experts now agree that chant as we know it developed much later, in the tenth or eleventh century, with no one person guiding its development.

For Benedictine monks, chant is a part of everyday life, sung five times throughout the day, right after rising and right before bed. Originally intended as a private and praiseful music-making activity, chant gained a small international audience in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries among fans of early music as well as New Age music, to the extent that Santo Domingo De Silos became a tourist destination. The monastery began renting rooms to members of the public willing to trek up a mountain to hear the monks essentially go about their daily routine.

While it had a few brushes with the mainstream, chant remained a niche market within a slightly larger niche market until 1993, when the Benedictine Monks Of Santo Domingo De Silos' Chant inexplicably spent a month at the top of the Spanish pop charts. Its success in the rest of the world was no less impressive. In fact, by the time it arrived in the States, it was so heavily hyped that the album debuted at number 12 on the classical charts, according to The New York Times, which reported that "some stores opened their shipments early." The next week it was #1 on the classical charts and #42 on the pop charts. Then it shot to #13. Then #3.

At the time many programmers and retailers weren't even sure how to classify Chant and the similar compilations that followed in its wake. Was it classical? World music? Religious? Did your local Sam Goody even have a religious music section? Reviewers, however, were generous, at times even hyperbolic in their acclaim. In a four-star review, Rolling Stone praised the album as "some of the most purely entrancing sounds ever composed. The no-frills recording of Spanish monks captures with perfect clarity the intensity and intimacy of this form of prayer."

Spin even listed it among the 10 Best Albums You Didn't Hear In '94, with publisher Bob Guccione Jr. himself writing, "Chant was not a novelty hit -- no one listens to an hour's worth of Latin religious poems sung a cappella for the novelty of it, not even people who go to raves. Chant works because it's stunningly beautiful and, literally, soulful. It elevates you viscerally. It's passionate and there's nothing contrived about it. And it's timeless, though after 1300 years, it might be a tad redundant to say that."

With such unprecedented buzz, Angel Records, the classical imprint of EMI, was forced to devise new ways to market the album. A rather ominous tagline exploited the timing, even though Y2k was still six years away: "Prepare For The Millennium." A single was prepared for the song "Alleluia, beatus vir qui suffer" ("Hallelujah, blessed is the man who stands the proof"), and MTV was reportedly interested in adding a video in heavy rotation. Such efforts, however, were hampered by the adverse reaction of the monks themselves, whose vows preempted tours, videos, television performances, or promotions of any kind. Eventually, the buzz wore on the monastery, and the monks decided it would be better to burn out than fade away. Angel did release Chant II the following year (that only reached #172 in the Billboard 200), and Chant III in '96, but they were comprised of years-old recordings. (A Christmas album, Chant Noël, was rushed out as well.) As Father Clemente Serna, the abbot of Santo Domingo de Silos, told the Guardian, "We are not used to this pressure and have decided to take a break. It will be some time before we make another recording."

That announcement ended the group's brief career and marked a turning point for the chant craze, which was quickly bogged down by knockoffs and parodies that compromised the defining principles of the music. Every label had to have its own squad of chanters, no matter how tenuous their claim to real chant might be. Sony Classical unleashed Gregorian Chant by the monks of Niederaltaich in Bavaria, and Deutsche Grammophon reissued The Mystery Of Santo Domingo De Silos, originally an obscure 1969 compilation featuring some of the monks who sang on Chant. Milan Records claimed two titles: Gregorian Chants, Eternal Chants and Heavenly Peace. Just the title of RCA Victor's Chill To The Chant sounded a death knell to the trend.

With each new release, the meaning and sound of chant changed gradually, with labels compiling an array of medieval music as Gregorian chant. A VHS compilation used chants by the Benedictine Monks Of St. Wandrille to soundtrack scenes of nature and architecture, no doubt playing like the chillest Ken Burns documentary ever. However, the landscape depicted on the tape wasn't the Swiss Alps, but the wilds of Minnesota, which is not a state noted for its mountains or monasteries. Whether these errors were egregious or simply slipshod is unknown and largely beside the point; they suggest a cashgrab mentality squeezing a musical form that was at its heart serious and self-denying. Chant simply wasn't ready for the relative vulgarity of pop.

Even worse than the rushed-to-market copycats were the lame parodies. How do you even make fun of monks? Don't ask the L.A. band Big Daddy, who notched a minor hit with Chantmania, their quickie exploitation as the Benzedrine Monks Of Santo Dominico. Their a cappella covers of "Losing My Religion" (get it?) and "Hey Hey We're The Monks" (OK, that's pretty funny) were half-assed, and it's doubtful they even listened to the music they were ribbing. In fact, their cover of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" sounds more like an overeager barber-shop quartet than a band of faithful devotees. An odd and obscure artifact today, Chantmania is comedy at its most cynical.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

One of the more interesting aspects of the chant craze was the constant meditation on why it was even happening. Any writer or critic reporting on the phenomenon was obligated to ponder that very question. Some were measured in their theories, citing the exotic quality of chant as well as its recent use as an element in dance music. Chant was popular in the early 1990s as chillout music, the ethereal quality of the recordings making them perfect for post-rave comedowns. More crucially, the a cappella nature of the music made it easy for DJs to mix chant with dance beats. In fact, just three years earlier, the German group Enigma enjoyed an international hit with "Sadeness (Part 1)," which superimposed chants over downcast club beats. The results, rather than sacred, were startlingly erotic: better suited to a softcore sex scene than to solitary prayer and personal reflection.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

As Joseph McLellan mused in the Washington Post at the time, "The popularity of [Chant] is easy to explain. The Santo Domingo De Silos monks sing beautifully -- not only with fervor and a fine sense of style, but with a sound more sensually attractive than the average monastic choir. I suspect that the acoustics of the monastery also help; there is a halo of reverberation around the voices that enhances the otherworldly effect." More broadly, he wrote, "Gregorian chant is the ultimate feel-good music: slow-moving, never loud, seldom making a melodic leap of more than a couple of tones; it's also intensely, ecstatically contemplative."

Bill Smith, vice president of Quality, which released the St. Wandrille VHS, wondered to Everyday Magazine if chant wasn't the musical equivalent of a stiff drink or a shiatsu massage: "The ideal setting is at the end of a long day, in front of a fireplace or in a comfortable chair or a couch. Really, you're sitting back and it's something you can really let wash over you. I've been listening to this type of audio piece for years at the end of a day. You need something to bring back balance in your life."

Other writers were much loftier in their theories. Writing in Entertainment Weekly, Greg Sandow posited, "Maybe spirituality is what the new chant audience is looking for. Lots of people, it seems, are wearied by AIDS, feudal wars, and other social problems that don't seem to have any solution. Gregorian chants offer deeper, longer-lasting values -- and, in fact, labels think they sell for precisely that reason."

Those explanations -- good music, relief from workaday stress, a palliative for pre-millennial angst -- aren't especially satisfying. Those conditions are common to any era. People are constantly wearied by social problems, even the occasional feudal war; people always need to relax, and they always like to hear good music. So why chant rather than some other musical form? Why wasn't Congolese Baka music, which formed the foundation of Deep Forest's '94 hit "Sweet Lullaby," just as popular? And why 1994 and not sooner or later?

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Chant in retrospect sounds like a comically extreme consequence of the decade's keep-it-real ethos, made by artists that shunned celebrity. At a time when Nirvana fans were still shocked by Kurt Cobain's suicide, when Pearl Jam were playing arena shows, when Stone Temple Pilots represented a second opportunistic wave of grunge acts, the Benedictine Monks might have sounded all the more attractive because they were incapable of selling out.

Or, perhaps more likely, chant simply appealed to a broad swath of people at a time when consumers were more willing to spend money on something new and exotic. It was, ultimately, a lowest-common denominator form of music for the time: classical, world, and religious. Oddly, even after the rights shifted to Blue Note, Chant seems to have fallen into neglect -- not completely out of print, but available at neither iTunes nor Spotify. Amazon still has copies of the CD for sale. Used copies are going for $.01.

But maybe that's ideal for artists who took a vow of poverty.