After a while doing this job, you hit a certain point. You've written about too many artists. Maybe all of your favorite ones. And you start to ask yourself some questions. You think, is there really anything I have to say about this new album? Am I really going to use all those favorite music-writer adjectives like "scuzzy" and "ethereal" once more for these new songs? You start to question the larger meaning of things. You start to think, all right, Stereogum, enough with the whole Young Classic Rocker Ryan Leas thing; I'm going to burn it down. You stare into the void and start to think things. And the void says something back. Then you decide, "Hey, I'm going to write an article defending the Red Hot Chili Peppers."

The Red Hot Chili Peppers are massively successful. There's no question about that. On some level, they don't need any defending. They've sold a ton of records, are one of the last truly massive and famous rock bands in terms of their reach but also in terms of being genuine celebrities. Even if their mainstream and critical clout has diminished in the last 10 years or so as they've taken increasingly longer breaks between albums while soldiering on in the absence of John Frusciante (the definitive guitarist for a band that has had several), their stature is solidified in a certain corner of the world. They are Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame inductees, for whatever that's worth. They will remain perennial and reliable festival headliners, they will sell out arenas. It doesn't really matter how the album they're releasing this week -- The Getaway, their first since 2011's I'm With You -- is received. They're one of those artists that's too big to fail. They aren't going anywhere. So while this has no bearing on their continued success, there is one nagging question when it comes to thinking about their stature and legacy in the grand scheme of these past few decades' worth of music: Well, wait, are they actually any good?

RHCP are a gateway drug. They're one of those bands that, if you are of a certain age, were one of the first that you got into. They were easy to discover and access, to listen to alongside Nirvana and Rage Against The Machine and the Sabbath or Guns N' Roses albums you'd find lying nearby in the record store for some reason. And there's a primitive likability about them when you're a pre-teen or a high school student. There were songs that seemed profound at the time, songs that seemed funny and illicit at the time. These were catchy and unpretentious songs that were sometimes impressive musically, but also weren't too hard to wrap your head around (or to play, if you were a musician yourself). There was a meat-and-potatoes simplicity about them, even as they were fusing genres -- funk, rap, metal, alt-rock, soft-rock -- in a more significant way than many of their contemporaries in the era of Alt Nation. And that genre fusion was part of the gateway drug, too, because once you got into this band, you could trace lines back to '80s hip-hop, or to Parliament/Funkadelic, or to Hendrix, or to punk.

The next logical step is that it was easy to outgrow the Chili Peppers. Musically, there was something about them that was inescapably goofy, and there's the fact that frontman Anthony Kiedis' lyrics often veered into juvenile poetics and straight-up prurience of the sort that doesn't translate well to a 2016 context. Considering the Chili Peppers often came off as a group of amicable man-children, it just felt like the kind of band you liked when you were 14 before moving onto more classic and/or more sophisticated options. For those of us who were growing up during RHCP's peak era, there was a cultural movement that paralleled our own gradual abandonment of the group. At some point in the '00s, the switch flipped. This band was positioned as a joke, like, "How did we ever invest this much in them in the past?" They were often a dumb rock band in an era that did not prize that whatsoever anymore. As indie moved to the mainstream and rock's scope diminished overall, artier and brainier artists took the spotlight, and RHCP increasingly feel like an anachronism of the pockmarked '90s alt-canon. You could argue that that this line of thinking was the result of trying to take a band too seriously, a band that was more self-aware and fun than many of the other idols with which we replaced them. Nevertheless, it's easy to find yourself in guilty pleasure territory if you talk about liking RHCP at all these days.

Yet these guys had their claims to legitimacy. They've associated with members of Parliament, Gang Of Four (somewhat acrimoniously, supposedly), and the Dead Kennedys. Elton John is on the new album. Kiedis is the weak link in terms of musicianship, having taken an amount of time that outstretches many artists' entire careers to get halfway-decent at singing, and still possessing a voice that's an immediate turnoff to some. Chad Smith is a great hard rock drummer, and Flea, though he often directs his talents toward mixed results, is a technically skilled bassist. In the last five years, he wound up making an afrobeat album with Damon Albarn, and recording/touring as a part of Thom Yorke and Nigel Godrich's Radiohead side project Atoms For Peace. Which means he was welcomed in by the exact kind of rock icons we would age up to from RHCP, the guys who were smarter or cooler or better songwriters, the guys we thought would surely scoff at all those teenagers listening to Blood Sugar Sex Magik and Californication.

Then there was John Frusciante. RHCP had a lot of members come in and out, mostly in the '80s, but the classic lineup of the band starts when Frusciante joins for 1989's Mother's Milk, and ends when he (seemingly finally) departs after touring 2006's Stadium Arcadium. The case of Frusciante and RHCP is a strange one. Here's a guy who, it would seem, shouldn't be interested in making this kind of music at all, even though he joined the band as a teenager and a fan. His interests always seemed more alternative and darker than where RHCP went, and he always came across as too much of a mercurial character to be onstage playing "Give It Away" for the millionth time. His second round in RHCP made a lot more sense, when he appeared to have more control and influence over albums like Californication and By The Way. Throughout that stint, he was also releasing lo-fi solo albums, electronic solo albums, solo albums that kinda sounded like a guy who had been involved in RHCP but was a lot more enamored with '80s college radio than Sly & The Family Stone. Regardless of any of that context, Frusciante is often (rightfully) praised as one of the greatest guitarists of his generation. This was a guy who could be technically impressive when he wanted to be, but displayed a great deal of taste in how he used his gift -- another remarkable characteristic, considering that if you're deriding RHCP, "tastelessness" is an easy and immediate criticism. Frusciante was capable of beautiful and simple guitar parts, of searing lead playing, and later ventured into finding strange and evocative sounds through an array of effects pedals. It was easier to look at Kevin Shields or Johnny Greenwood and spot a visionary, but that's a disservice to what Frusciante was: a guitarist in more of a classic rock mode who had an interesting way of adapting to the contemporary landscape. No matter what RHCP's standing in the world, it always seems acceptable to like Frusciante, at least; the comment that often follows is that he was too good for RHCP, and deserved a greater artist to have been involved with.

The thing about Frusciante was that he wasn't this weirdo that stumbled into the jocks' friend group. One thing you have to give RHCP credit for is that this was a couple of unrepentant goofballs who somehow became massive rockstars in an era defined by brooding, authentic rockstars. And it's not like RHCP didn't have their own demons and drama. Addiction has plagued this band, between founding guitarist Hillel Slovak dying of an overdose in 1988, and both Kiedis and Frusciante's well-documented struggles. On some level, you can celebrate RHCP for being RHCP in the face of everything. They were never trying to be the cool kids. And they mostly remained this affable band looking for the joy in life even amidst all the damaging experiences they had in their lives. That's where there is a sense of elitism in writing them off as "That band I liked when I was fourteen, that band for kids before they know the real shit." The Chili Peppers' success can't all be a fluke, and there's something inspiring in these four weird dudes somehow ascending to the point they have, and the fact that they are so comfortable plugging along doing their thing in a world where they could be regarded as embarrassing.

That being said, their discography remains wildly uneven. The stuff that would be considered the classics (Blood Sugar, Californication) have their duds, and their cringeworthy moments. Moments of maturation and increasing sophistication in the late '90s and early '00s were met with some people missing the simple pleasures of this band, others not finding them to be a band actually capable of maturing, and then the band losing ground in later years. Personally, I'm the type of RHCP apologist who would've been curious to see where they could've gone had they kept pushing in the direction of Californication and By The Way while further abandoning their old ethos entirely. That's not how it went down. Stadium Arcadium brought back a lot of the funk and silliness, and then Frusciante left. While Josh Klinghoffer is a serviceable replacement, there's a void left behind by Frusciante, with even the good (or occasionally very good) newer RHCP songs feeling somehow stilted without his touch.

With the announcement of The Getaway, RHCP released a song called "Dark Necessities." I'm in the camp that really likes it, and finds it a promising preview of the new album. It's the first album in forever that Rick Rubin hasn't produced for them; instead, they hired Danger Mouse as producer and Nigel Godrich as mixing engineer. The other new songs made me a little doubtful, but "Dark Necessities" initially made me think we could be getting a middle-aged RHCP that really worked.

That last statement is kind of the bump in the road here. Perhaps this is anecdotal, but I find that if you're defending RHCP in any context, it's a conversation laced with caveats. You have to forgive amateurish lyrics, the lack of maturity, the big-budget rock production that ages some of the older stuff, whole albums that are more or less just bad, and the big joke hanging over it all, both in how the band is regarded and how they carry themselves. Defending RHCP from a certain angle means, essentially, finding the moments you still really like and wishing for an alternate history in which the band was, overall, quite different than they actually were. Obviously, that isn't going to happen, no matter what The Getaway sounds like. But with this impending new album, I decided to dig back into their catalog and find evidence of why this band got to where they were, why I might've liked them at some point or another in my life, or why they might still warrant my (or your) loyalty. This list focuses on a few albums and isn't meant to be comprehensive, but no matter how corny or childish the Chili Peppers can be, there are some songs of theirs that, I'd argue, definitely don't suck. If you have the energy and desire to sift through the nonsense and forget the fact that this group of weirdoes got co-opted by a generation of bros, there are a lot of gems in the mix, and certain counter-narratives to how we can look at RHCP's career. Here are nine songs that make that case.

"Under The Bridge" (Blood Sugar Sex Magik, 1991)

Blood Sugar Sex Magik still stands as the RHCP album most would readily regard as their best. It was their breakthrough, and it was one of the big alt-rock albums of the '90s. Yet a lot of it is that younger, doofier version of RHCP. It has its charms, and it has a lot of moments that are really grating. Within all that were a few mellower songs, like “Breaking The Girl,” their (pretty good) attempt at Led Zeppelin III, and “Under The Bridge.” The latter is one of the iconic alt-rock songs of the '90s, a more personal story from Kiedis about his time lost doing drugs in LA, and the alienation he felt while maintaining his sobriety in an industry (and band) that wasn't a great setting for his new lifestyle. Even amongst all the inane stuff on Blood Sugar, there was this glimpse of something a lot more adult, a lot more real. As much as the Chili Peppers could come across as adolescent types, Kiedis had been through some shit in his life, and he funneled that into “Under The Bridge.” It was a song crucial to their attaining a wider mainstream success, and while it's a song we've all heard a million times, that dramatic chorus at the end still packs a punch.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Aeroplane" (One Hot Minute, 1995)

One Hot Minute is the weird stepchild of RHCP's catalog. It's an outlier in their peak era -- the era in which John Frusciante completed the band's best lineup and they achieved their greatest success -- because it's the one album they made without him during that time. He quit amidst the heightened fame that came with Blood Sugar Sex Magik and spent the mid-'90s disappearing into addiction, and they hired Jane's Addiction's Dave Navarro as his replacement. Navarro's style (and lifestyle), combined with Kiedis' relapse, yielded a darker, druggier, loopier Chili Peppers album. To the extent Navarro's influence was felt, it resulted in RHCP songs that felt sorta like the band we knew, but with heavier edges or more psychedelic embellishments. "Aeroplane" was of the latter category, a single that oscillated between funk verses and a sickly sweet sing-song chorus (later augmented by a choir of children to drive home that vibe). It's one of the moments where the skewed nature of One Hot Minute works. "Aeroplane" makes sense alongside many of the band's other, more famous singles, but its hooks have a queasiness to them that ensured you wouldn't hear it in the mall all the time like, say, "Give It Away." That also means it wasn't as overexposed, which in turn has let it stand up as one of the more enduring RHCP tracks out there.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"One Hot Minute" (One Hot Minute, 1995)

Navarro was a mismatch for RHCP, bringing with him a more twisted element that never really made sense in the band's universe. In hindsight, you can look at much of One Hot Minute as him trying to fit into their mold until Frusciante's eventual return. There aren't many songs where his disposition actually helps them stumble upon something entirely new, and even when they click, that mismatch is still apparent. Perhaps the foremost example of this is One Hot Minute's title track, a song that structurally and melodically actually recalls Jane's Addiction more than it sounds like RHCP. "One Hot Minute" is a lurching, volcanic rock song, the kind of thing that seems to be precisely balancing itself on the edge of coming apart altogether at any moment. Like other moments on One Hot Minute, Kiedis as slapstick rapper seems a lost memory; he sounds more deranged and haunted here than almost anywhere else in the band's catalog. None of that is intended as "This is a thing RHCP never were or should be, so that's why this one's actually good!" This was just one instance where their short-lived partnership with Navarro resulted in a damn good anomaly. "One Hot Minute" is the group exploring more intense places than they usually tread, ratcheting up tension until the song rips open into the chorus. They'd never sound as tormented again, but this is another RHCP oddity that's worth returning to.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Otherside" (Californication, 1999)

Generally speaking, there are two primary versions of RHCP: the hard and goofy rap-rock-funk hybrid, and the softer, occasionally introspective California-alt identity that they embraced fully on an album named, naturally, Californication. The album was a big deal: the return of Frusciante and something of a comeback for the band as well after One Hot Minute, the introduction of a different and (slightly) more mature RHCP, stratospheric pop success. True, there are some who lament the loss of that jocular, younger RHCP, and sure, we already know a lot of these singles in and out. But if you're approaching RHCP from the viewpoint that what they were originally known for is not that great, and that they're better when they shift toward a different version of themselves, then Californication and its undying singles are the crucial turning point. One of the best of these is still "Otherside," a song that features plaintive singing from Kiedis and one of the nimbler rock tracks the band has in their arsenal. There are no thudding funk-metal angles here, just an instrumental that glides until it knows when to ignite. Featuring not only customarily tasteful guitar work from Frusciante but also his harmonies buoying Kiedis' lead vocal (an interplay that was one of the band's secret weapons), "Otherside" is at once one of the band's more memorable, pretty, sad, and cathartic singles.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Californication" (Californication, 1999)

Hey, did you know that the Red Hot Chili Peppers really love California? Did you know that like, a ton of their songs are about California? Of course you did. It's one of the easiest ways you can make fun of them. The inevitable silliness of the made-up word "Californication" notwithstanding, however, this was a more emotive reflection on the band's home state. This was before we got to the cartoon of "Dani California," and Kiedis' big "Califoooorniaaaa" chorus teetered headlong into self-parody. "Californication" played like a meditation on the dark side of the Golden Coast's lure, and while there are naturally still some nonsense lyrics, RHCP sell it. There are some interesting deep cuts on Californication, like "This Velvet Glove" or "Savior," that might be more revelatory inclusions on a list like this, but there's something about "Californication," for all its ubiquity, that still makes it a good listen. There's an understated, melancholic quality here that, while introducing a new version of RHCP, would also be a quality they wouldn't be able to harness as deftly in the future.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"By The Way" (By The Way, 2002)

By The Way is consistently the poppiest RHCP album, with the least evident funk or hard rock influences. Some people don't go in for that. Some people, like myself, would play contrarian and argue that this was the band's finest moment, but that's an argument for another day -- aside from the fact that there are three By The Way songs on this list. Its title track is something that should be annoying by now. It was another massive hit that you have heard ad nauseam, I'm sure. But there's something about hearing "By The Way" again that's always welcome. Like "Otherside," it skillfully mixes the band's softer voice and harder edges; it's a pretty effortless composition, sliding from a quiet beginning that quickly ruptures into the shuddering verses, before that tension bursts into the song's huge chorus. Even Kiedis' characteristically garbled word soup during the rap parts is easy to write off for the sheer percussive catchiness of how he's using his voice here. The song is just over three and a half minutes in length, but it's a masterful bit of contemporary pop craft, with the band cramming more colors into that short timespan than they used to wield altogether on earlier albums. It should be a mess, but instead it works perfectly.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Don’t Forget Me" (By The Way, 2002)

In many ways, By The Way felt like Frusciante’s album. His voice prominently accompanied Kiedis’, the sonic direction was rooted mostly in his interests, and his guitar playing here was some of his finest. There’s the guttural mechanics of the “Throw Away Your Television” solo, the sprightlier funk of his earworm “Can’t Stop” lead, and ghostly pop of the interlocked guitars in the first part of enigmatic-then-euphoric closer "Venice Queen." Then there’s the gorgeous work he does on “Don’t Forget Me.” Through the verses, Frusciante doesn’t quite play a concrete part -- there’s no riff, no idle strumming, but instead spectral, perpetually-aggrieved notes puncturing the song from a distance. Again, you have to let some of Kiedis’ lyrics slide, but between Frusciante’s playing and the universal pang of the title in the chorus, there’s an emotional pull through the song that culminates in one of those stunningly simple but gut-wrenching solos Frusciante could so so well. There are a few moments in RHCP’s catalog where they can convincingly pull off this kind of mourning, and as a showcase for Frusciante, “Don’t Forget Me” ranks amongst their best work in that vein.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Animal Bar" (Stadium Arcadium, 2006)

A double album from the Red Hot Chili Peppers is more than most sensible people can stomach. But Stadium Arcadium was a fitting conclusion for that phase of RHCP: the final album to date with Frusciante, a sprawling thing where the band attacked almost every sound in their wheelhouse. That resulted in some songs that had a few too many ideas in the mix, where one promising part gave way to a confounding left turn. It also resulted in the second disc of Stadium Arcadium (dubbed "Mars"), being a fairly strange, all-over-the-place work if you were to look at it as a standalone RHCP album. There's the wiry, dramatic build of "Turn It Again," the eeriness of "We Believe," and a whole lot of mellow, introspective stuff with "She Looks To Me," "Hard To Concentrate," and "If." Amidst it all, there's "Animal Bar." The verses of "Animal Bar" are uncharacteristically spacey for the Peppers, but they also stand as some of the lowkey prettiest moments on Stadium Arcadium, with Frusciante's guitar working in abstracted waves. The chorus is one of those aforementioned confounding left turns that litter the album. It doesn't necessarily ruin the song, but it keeps it weird -- like this was a glimpse of something that could have been really special, and it got halfway there. Still, those verses are pretty damn cool.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"Desecration Smile" (Stadium Arcadium, 2006)

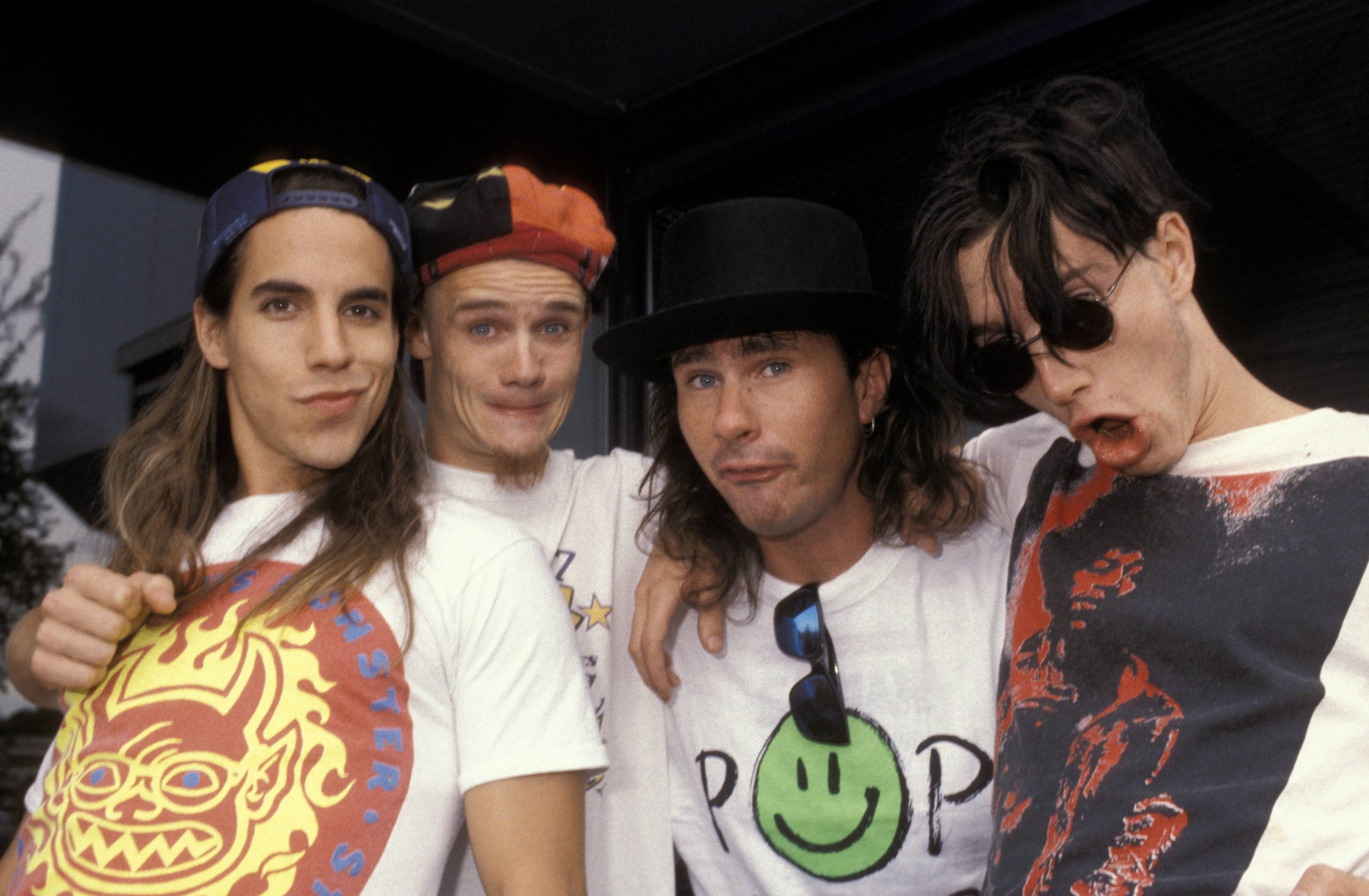

The video for "Desecration Smile" is a simple one, mostly featuring the four members of RHCP huddled together and singing along, or clowning around. As one of the final singles released while Frusciante was in the band, it now plays like a warm elegy for one era of the band. The song itself is a good companion for that sort of sentiment. It's a dusty, mid-tempo track leaning into the band's more emotive side. It bursts out into a chorus that has one of those Kiedis lyrics that's kinda silly and doesn't entirely make sense but half-works in context ("The love I made is the shape of my space/ My face, my face"). There is a bit too much on Stadium Arcadium to sort through, or to be worth sorting through, but stuff like "Desecration Smile" stands as material that, while not pillars or peaks amidst the Chili Peppers' work, are quietly endearing and pretty in their own way. With much of their post-Frusciante work feeling somehow half-done and/or anemic, "Desecration Smile" lingers as one of the last great sad-pop RHCP songs that boasts one of those choruses promising the better times that, if anything, RHCP are gifted at conjuring.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]