I saw Trainspotting with my dad. This was a bad idea. I don't know what I was thinking. If I'd gone with literally anyone else, I could've gotten lost in one of the most purely kinetic, exhilarating moments that '90s cinema had to offer. Instead, I had to glance nervously over at him every time shit spattered the walls or a dead baby crawled on a ceiling or Begbie smashed a glass over somebody's face, just checking in to make sure steam wasn't actually coming out of his ears. I had to anticipate the inevitable excruciating drive-home conversation about why I'd wanted to go see a movie about these fucking lowlifes in the first place. (Interesting twist: He was mostly appalled over Renton not blaming himself enough for Tommy's death, leading me into one of those babbling, "Um well if you'd read the book..." justifications.) I had to hope against hope that all the gross things that I knew were coming wouldn't turn out to be too gross. (They all were.) And even after that godforsaken traumatic experience, I still walked out of that movie wanting to be a Scottish junkie. Such is the power of a good movie.

The main reason I walked out feeling like that was the music. Director Danny Boyle never quite showed that same flair for pairing the exact right image with the exact right song again, but Trainspotting showed a whole system of tastes at work. In Irvine Welsh's source-material novel -- written entirely in a phonetic, nearly impossible-to-read Glasgow dialect, which, like A Clockwork Orange before it, made it weirdly irresistible high-school reading -- we'd learned about these people and what they were into. Welsh's characters loved Iggy Pop and David Bowie like gods, but they were intrigued by both the music and the drugs of the whole rave subculture. That was compelling enough. But to see that actually captured on film, the images made to pulse and move with the music, was another thing entirely. The whole thing was a masterpiece in music supervision. The former EMI A&R Tristram Penna has said that Boyle originally wanted to use David Bowie's "Golden Years" for the opening sprint, but Bowie turned the movie down. Iggy Pop's "Lust For Life" was a fallback choice, but it fits so well with the image of Ewan McGregor madly careening away from police that I cannot imagine another song in its place, the same way I can't imagine anything other than Lou Reed's "Perfect Day" thrumming blissfully the moment McGregor finally slips into overdose.

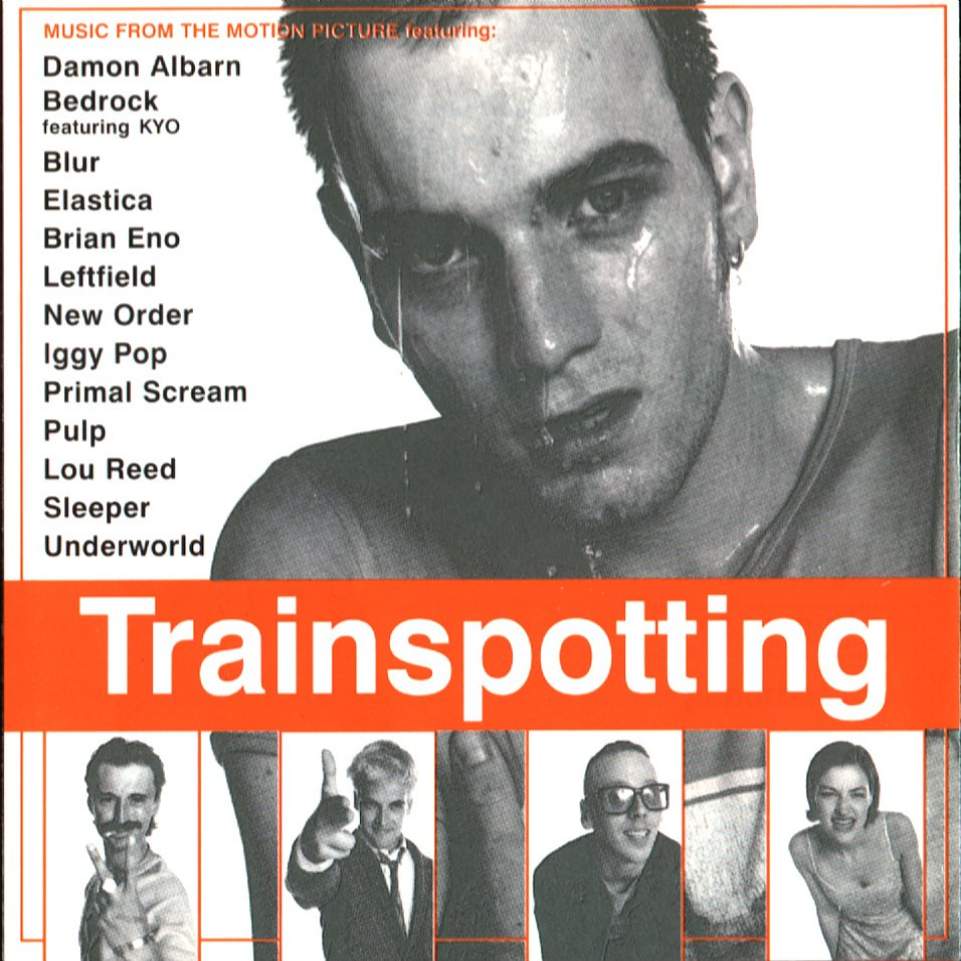

For a kid like me, a suburban American teenager just starting to become fascinated with the whole Britpop explosion, the Trainspotting soundtrack was a crucial document. In its song-selection, it placed Pulp and Blur in a British-music continuum, one that went from the absent Bowie through New Order and into the rave explosion. It helped that the soundtrack's compilers got honest-to-god good songs from most of the leading lights of UK music at the time. Pulp's "Mile End," with its playful shuffle, and Elastica's "2:1," with it spartan skank, could fit comfortably alongside the album's classics, and the only real throwaway -- other than maybe Sleeper's note-for-note cover of Blondie's "Atomic," which had the blessing and curse of sounding exactly like the original -- was Damon Albarn's album-ending solo track "Closet Romantic," in which Albarn foreshadowed much of his halfassed post-Blur work by intoning the titles of Sean Connery Bond movies over dinky synths and horn-farts. (This was the song that finally brought me around to the idea that maybe Oasis were better.) And the dance tracks fit in, too. They had a tension that wasn't there on the Britpop songs, and it was exciting to think that British kids going out to get fucked up had all these different aesthetic options.

The albums two centerpieces weren't just non-throwaways; they were songs that would reshape the careers of the artists who made them. Primal Scream had been coming off their disappointing Stones jack Give Out But Don't Give Up, and their 11-minute instrumental dub odyssey "Trainspotting" pointed its way forward to the sinister atmospherics of the comeback they'd enjoy with Vanishing Point the next year. Looking back, it's so weird to think a band could've gone from "Rocks" to that in just two years. It's not just a one-off lark; it's a complete reinvention for a band that was just recapturing its own vitality. And then there's Underworld's epic "Born Slippy .NUXX," the soundtrack's signature track and one of the great anthems of its day. (Underworld had already released this version of "Born Slippy," but they made it a single after Trainspotting.) "Born Slippy" couldn't have been more perfect for that final scene in the movie. It had all the tension and ferocity of something like Iggy Pop's "Nightclubbing," another track from that soundtrack, as well as the starry-eyed grace of, say, first-album Stone Roses, who would've fit just fine on the soundtrack. And it brought those things all forward into the dance-music present. It swirled everything together until it was its own thing, an anthem that will always evoke an era. Even sitting next to my dad, waiting for the movie to finally end, waiting to make my escape, I felt that.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]