From 1996 - 1999, I worked at a New York City record store called Rebel Rebel. I was a student at NYU when I got the job, and then I graduated from school but stayed at the shop. These were the Golden Years, although we didn't realize it at the time.

Rebel was located in Manhattan's West Village, on Bleecker Street between Grove and Christopher, and when I worked there, we were literally surrounded by record stores. Record Runner was around one corner, Rockit Scientist around another, and House Of Oldies around yet another. We had one Kim's Music And Video outpost maybe three blocks to the west of us, and a different Kim's Music And Video outpost maybe eight blocks to the east. Bleecker Street Records was two minutes away. Other Music was 10 minutes away. Across the street from Other Music was Tower Records. If you made a left out of Rebel and kept walking in that direction just long enough to cross 6th Avenue, you'd hit Bleecker Bob's, Second Coming, and Generation Records before getting to Washington Square Park. There was a record store whose name I never knew literally across the street from Rebel, and another record store whose name I never knew two blocks away. There were at least half a dozen more that I sorta remember, and probably two dozen more that I've forgotten entirely.

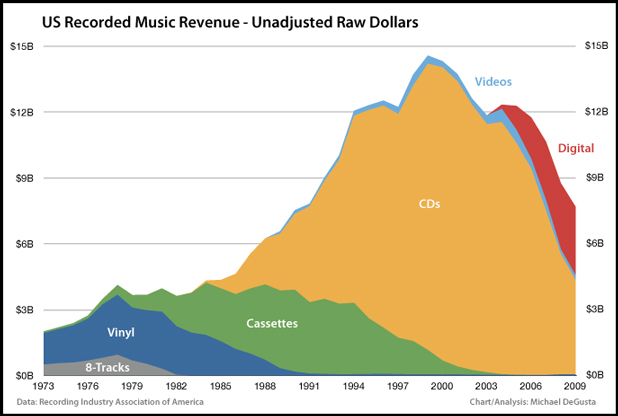

I'm not kidding about the Golden Years thing; my time at Rebel coincided exactly with the US music industry's peak moment, and when I finally left -- to get a real job -- the arrow made an abrupt downward turn. Here, Business Insider made a chart. Just look at all that gold.

Soon after that, the stores started closing. The reason was piracy, they told us, and iPods, and iTunes, but that wasn't the real reason, I don't think. I think the stores closed because big-box chains like Best Buy started treating CDs as loss leaders, as bait, offering them at less than wholesale -- that is, selling them for $2 or $3 below what they paid for them. (It was pretty common for independent shops to send floor employees to Best Buy every Tuesday to scoop up armfuls of new releases for $10 apiece, which would then be marked up to suggested retail for sale in the store.)

I mean, look, the stores were probably gonna close anyway eventually, but the way it happened -- everything all at once like that -- they didn't even have a chance to defend themselves. Piracy was nibbling at the edges, and the iPod offered a powerful alternative to physical product, but the big-boxes made it IMPOSSIBLE to compete, to adapt. There were too many forces working against the record stores, so they started blinking out like Christmas lights.

It wasn't just one thing, but it's never just one thing. It was a lot of things conspiring. And then, the collapse.

But let's go back to the Golden Years for a minute. Along with its generous selection of record stores, that particular part of New York City was also populated by a lot of rich folks, tourists, and celebrities. I honestly couldn't believe how many famous people shopped at Rebel; I couldn't even keep up. I saw Eddie Vedder in there, and Naomi Campbell, and Mike Piazza, and Quentin Tarantino ... Maura Tierney and Debbie Mazar were regulars. So were Shalom Harlow and Amber Valletta. Michael Stipe. Bob Mould. Here's a good one: Two years before the High Fidelity movie came out, I sold a copy of The Three EPs by the Beta Band to David Johansen. That's a true story! But it's not my favorite story. THIS is my favorite story (and if you know me in real life, you've heard this one before):

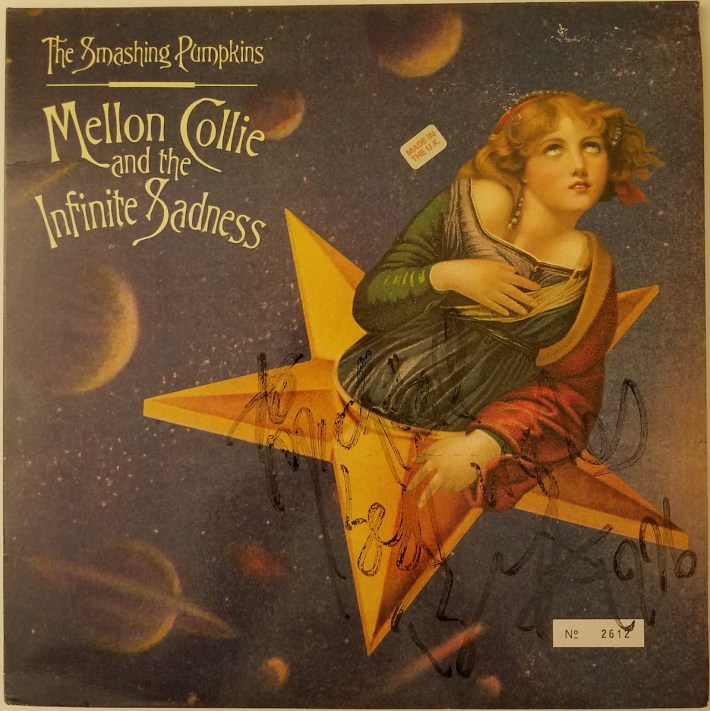

One weekday afternoon, I was on a lunch break, on my way back to Rebel from Joe's Pizza, carrying two plain slices in a box big enough to fit a large pie, when I saw, walking in my direction, Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan.

There's a sort of understood New York City etiquette that requires residents to not approach or even openly notice celebrities on the street, but Billy Corgan was very high on my list of the Greatest Musicians In The Universe, and just this one time, I couldn't stop myself. I carried my pizza box right up to the poor guy and just started chatting, treating him like we'd been friends forever, like I was just mildly surprised to be running into him out of the blue. "Hey Billy! What are you doing in New York, man?" That kinda thing. To his eternal credit, he received me equally warmly, possibly because he thought we did know one another, and he was having trouble placing me. Anyway, he was in town for something or other; I can't remember. Then I hit him with the ask:

"I work at a record store down the street. Would you mind coming back with me so I can get an autograph?"

He thought about this for a second -- trying to come up with a way to turn me down gently, I'm certain -- and then answered my question with a question of his own. He'd just bought a vintage jukebox, he told me, and was looking to stock it with cool old 7"s. So, he wanted to know, did we sell vinyl?

That seems like a silly, self-evident thing in 2016, because in 2016, you can't have a record store without vinyl. CANNOT, end of story. But in 1996, it wasn't necessarily a given. As it happens, though, we did sell vinyl -- our customer base included a lot of obsessive collector types and club DJs and wealthy Europeans who were hunting for bizarre Bowie artifacts, so we actually specialized in vinyl. I told Corgan as much, so he ditched his girlfriend who had wandered into some store or something (not kidding; he said, "She'll find me"; this was pre-cell phone era) and walked back to Rebel with me. He bought a stack of singles, and I pulled an LP off the wall for him to sign. Needless to say, I still have it.

So anyway, the stores started closing, but somehow ... Rebel didn't. This is not because Rebel was New York City's best record store by any objective measure. It was the size of a minivan and had the disintegrating-cardboard ambience and deranged self-styled "organization" of a hoarder's attic: dangerously crowded with stock that formed in gravity-defying piles eventually reaching the tin-plated ceiling and, in places, pushing through to the floor above. The people who worked there were total legends and absolute sweethearts, of course, but I won't lie: We weren't always in the best of moods.

Still, it survived. And the reason it survived, I think, was ... well, the location, naturally, because that's paramount, but remember, lots of places in the immediate vicinity didn't survive. So it wasn't just one thing, but it's never just one thing, and in Rebel's case, the big thing? Vinyl. That was the store's specialty at the height of the CD era, so the store was unusually and even unwittingly prepared for the market shift, the vinyl resurgence. This past April, Gothamist made a list of New York City's best record shops, and Rebel was on it. Here's what they had to say about the place:

[I]t's a ridiculously cramped shop, with stacks and piles of records (some of them with no sleeves) spilling all over the place. In a way, though, it's perfect. Rebel Rebel feels like a crowded, unruly rock concert and maybe that's what digging for punk rock vinyl is meant to be after all.

That's kinda nice, huh?

And soon after that article came out, sometime in the middle of June, it was announced that Rebel's doors would be closed forever by month's end, after 28 years in business. This came the exact same weekend as the shuttering of another longtime New York City record shop, Other Music, which had been around for 21 years. The New York Times wrote a lovely eulogy. The title? "Vinyl Mania Can't Save The Greenwich Village Record Stores."

A photo posted by Abe Friedman (@abefreedom) on

OK, end of wistful reminiscence; onto the hard stuff. In last week's column, we talked about the Nielsen Music 2016 Mid-Year Report, keeping our focus on the industry's inconsistent and seemingly arbitrary attempt to translate streaming numbers to "sales." But the report extended to traditional-sales data, too, of course. The news in that category is largely unpromising -- CD sales are down 11.6 percent compared to where they were over the first six months of 2015, and digital album sales are trending even worse, down 18.4 percent. The one area of growth? Vinyl, which is up 11.5 percent, with total sales of 6.2 million units. The Nielsen report's "Highlights" section included this optimistic observation:

• Vinyl continues to become a bigger piece of the physical music business. Vinyl LPs now comprise nearly 12 percent of the physical business in the first half of 2016, which far surpasses last year's record pace of 9 percent.

This is statistically accurate! If you go back and look at the 2015 mid-year report, you'll see this bullet-point item among the "Highlights":

• Vinyl LP Sales Up 38 Percent YTD -- Now Comprise Nearly 9 Percent of Physical Album Sales

So vinyl has gone from comprising nearly 9 percent of physical album sales in 2015 to nearly 12 percent in 2016. BUT -- as much as it pains me to say it -- that's not the important figure here. In fact, that statistic is basically useless to us. See, vinyl's overall share of the "physical" market is pretty irrelevant, because its increase in that regard has less to do with the growth of vinyl than it does the decline of CDs. The thing to focus on here is that "38 percent" figure. If we want to get a feel for the viability of vinyl going forward, we have to isolate that data; we have to compare apples to apples.

In the first half of 2015, vinyl sales were up 38 percent over the same period in 2014. But in 2016, vinyl sales are up only 11.5 percent over the same period in 2015. That's a bad sign, made worse when you look back even further. As we covered at some length in the 2015 wrap-up, when we're looking for signs of growth in business, we're not really focusing on total sales, but year-over-year percentage changes. Wanna do a chart? Let's do a chart. Here are Nielsen's vinyl sales data for the first halves of the last five years, all stacked up:

[photoembed id="1889742" size="full_width" alignment="center" text=""]

That's a pretty clean-looking arc, is it not? And if that arc continues on that trajectory (and I'll be shocked if it doesn't), vinyl sales are gonna plateau sooner than later. And not long after they plateau, they're gonna crater. See, the entire vinyl resurgence relies unhealthily on a couple things: (1) positive press (which will turn into negative/skeptical/doomsaying press the moment the numbers flatten out); and more importantly, (2) sales accumulated on one day of the year.

Yes, Record Store Day only occurs on a single Saturday in April, but it governs the movements of the entire market, largely because there is a limited number of vinyl-pressing plants in the world, and some of them are reportedly backlogged for six months with RSD-specific orders. That's become an issue affecting the entire industry all year long. As Fact Mag wrote in their 2015 piece "Record Store Day: Problem Or Solution?," independent labels have myriad grievances regarding Record Store Day, but "vinyl turnaround times [are] top of the list."

But as any decent motivational meme will tell you, the Chinese word for "crisis" also means "opportunity." I.e., this is not even an issue! Just open more plants -- problem solved, ya whiners -- and make a few bucks while you're at it! No? Seems like a pretty obvious solution.

In that spirit, spotting a chance to match a well-publicized demand with a seemingly much-needed supply, numerous organizations and entrepreneurs have rushed in to fill the void and offer alternative options to those labels fed up with the RSD logjam. In September 2015, The New York Times ran a piece called "Vinyl LP Frenzy Brings Record-Pressing Machines Back to Life," sharing the story of Dave Hansen's Independent Record Pressing, a newly opened plant that had refurbished and restored more than a dozen out-of-service vinyl-pressing machines, at a cost of $1.5 million to the company's investors. Here's my favorite line from that article:

To replace an obsolete screw in one machine, Independent spent $5,000 to manufacture and install a new one.

Yikes! Moving on: This past April, The New Yorker ran a similar feature, this one titled "New Hope for Record Store Day's Vinyl-Supply Troubles," highlighting even more aggressive strategies being employed to capitalize on vinyl's growth.

[I]n the past four months, two companies, Germany’s Newbilt and Toronto-based Viryl Technologies, have introduced the first new record-pressing machines to hit the market in decades. Viryl's is the more advanced of the two: a fully automated, computer-controlled press called the Warm Tone [which] will cost a $190,000, more than double the cost of a restored record press, or one of Newbilt's. But Viryl believes that there is enough demand to justify the price. "There are a hundred and thirty-five working record presses in the US," Alex DesRoches, the company's head of marketing, said ... "If we continue to see 30-percent annual growth in record sales [the figure for 2015], something has to give."

Hmmm ... OK, right, but ... well, what happens when we don't continue to see 30-percent annual growth? What happens when it drops to, say, 11.5 percent?

What happens when it drops to 1 percent?

What has to give then?

(Incidentally, did you know that the Chinese word for "crisis" actually does not also mean "opportunity"?)

Lets go back to that Times piece about Dave Hansen and Independent Record Pressing for a sec. I already shared with you my favorite line from that article; now, here's my least favorite:

Mr. Hansen, 52, said he wasn't sure whether the vinyl gold rush would continue, either, but he has staked a considerable personal investment in it and called the plant part of his retirement planning.

Heartbreaking, right? Hold on. It gets worse.

The problems created by Record Store Day extend beyond turnaround times, of course, but I won't try to draw for you a complete picture, because that picture has been drawn so freaking many times already. In brief: Independent record stores feel the event has been "co-opted by major labels who want to get their product of new vinyl into stores." Meanwhile, independent labels feel the event has been "co-opted by major labels and used as another marketing stepping stone."

Seems like there's a common enemy here, huh? Let's be fair, though. Gotta hear both sides.

To that end, we've got Billy Fields, aka Warner Music's "Vinyl Guy," who wrote an op-ed for Billboard this past April, in which he offered a rebuttal to the many "labels, journalists, store owners, and various prognosticators [who feel] Record Store Day is a bad idea." Before getting to the meat of his argument, Fields used his forum to challenge some commonly held misperceptions about the faction of the music industry in which he works (taking an oddly defensive stance for a piece published by a music-industry trade magazine, but that's neither here nor there):

I work for Warner Music Group. There, I've said it. I work for a "major." You probably imagine I drag my butt out of bed every day to sit at a desk in a cave with accountants and lawyers running around telling all the music heads what to do and how to do it ...

... but, guess what? That isn't how it is. Not even close.

Instead, I work in a vinyl-lined den of analog, referencing both our newest records as well as quality used finds from the past. I work with label and management contacts to ensure we're doing everything we can to make the best records possible but, most importantly, records that our artists want us to make.

"Vinyl-lined den of analog." What does that even mean exactly? Unclear. Fields' title is Vice President, Sales, Account Management For WEA, i.e., "the artist and label services arm of Warner Music Group," and here's how Billboard describes his role:

Fields serves as the day-to-day conduit for independent retailers and the three major independent music coalitions, overseeing all aspects of vinyl production, planning, marketing, sales forecasts, projections, and strategy.

Kinda weird that he doesn't sit at a desk alongside accountants and lawyers, but hey, every company handles its "marketing, sales forecasts, projections, and strategy" in its own way, I guess. No matter! After that bit of throat-clearing, Fields got to the good stuff. I'm tempted to just cut-and-paste his entire polemic below, because it's full of heartstring-tugging platitudes that will seem so richly ironic in a minute or so, but I'll restrain myself and excerpt only this section:

Record Store Day is many things but, at its very core, it is a collective of independently minded entrepreneurs who work hard to make an unforgettable yearly event by wrangling indies and majors alike. RSD's small core of organizers come directly from independent music stores, or oversee independent retail coalitions. They want every music fan to find what they are looking for, even when their favorite band only made 1,000 copies because that's exactly what they (their favorite band) wanted to do. They want every store, big or small, to make a meaningful profit so each store can grow or continue on as each sees fit. They want music retail to flourish for the next 10 years, the next 20 years, the next however-long-it-takes, until all our music is piped in direct to our brain stems.

Record Store Day ain't perfect, but it's close. Where would you rather spend your third Saturday in April each year? I'm going to a record store, or seven.

I'm assuming Fields doesn't live in New York City, because I'm not sure he could find seven record stores around here. But I digress. Last week -- less than three full months after Fields penned that plea for Billboard -- Pitchfork published a story titled "Warner Music Issues Potentially Devastating Blow to Small Record Stores." Here's the salient info:

WEA, Warner Music's distribution and marketing arm, has shut down the accounts of "about a hundred" retailers that did less than $10,000 in business with the company last year, a WEA source has confirmed to Pitchfork. The move put into effect an existing policy requiring a $10,000 minimum annual order for stores holding direct accounts with WEA. This could have a devastating effect on small record stores around the country, representatives for various shops tell Pitchfork ... Small businesses that can’t afford to order directly from WEA will now have to order through intermediaries. [One store owner] said that will be more expensive and lead to higher prices for customers.

You can't make this stuff up. You can't! But wait, there's more. This past April, Fortune published a piece outlining some additional challenges being imposed upon retailers by those execs hidden away in their vinyl-lined dens of analog. Namely?

Prices have jumped by as much as 75 percent for new major label releases since last summer after the major labels began raising prices on new releases last spring ... The price hikes have left shop owners choosing between charging higher prices or cutting their own profit margins to keep current titles stocked ...

[Randy] Boyd at Cobraside Distribution works with 300 to 400 stores nationwide and says his sales are down 20 percent to 30 percent from last year. "The buying public is rebelling at the new, higher prices," he says. "I think over the last 12 months we're trying to sell into a headwind. When the vinyl resurgence started 10 years ago, new vinyl was $16 and so was a CD. Now the CD is $10-$12 and the vinyl is $30. Many people aren't that committed to vinyl."

Again, in 2016, you can't have a record store without vinyl. But can you have a Record Store Day without record stores?

I'm not saying all the record stores are gone or are going away, or that new record stores aren't opening here and there every day. I'm not saying trends in New York City will reflect those in Nashville or Phoenix or Chicago. I'm not saying the end of Rebel Rebel means the end of vinyl. Man, I'm not even saying the labels' horrible bottom-line maneuvering had anything to do with Rebel shutting its doors. In fact, I'm well aware that the two things are entirely unrelated. Rebel got forced out because New York City retail storefront real estate prices are fucked. Even Starbucks can't afford it here.

What I'm saying is that I know what a record store's margins look like, and I know there isn't much wiggle room for retailers anywhere. I worked in a record store at a historically anomalous boom moment and I still couldn't understand how the hell we stayed in business when I saw how goddamn much we ordered, how much we marked it up (not much), and how much we sold, day in and day out.

I'm saying if your prices go up, customers don't care why, they just start looking for places where they can get the same thing for less money. In the early aughts, that was Best Buy. Today, it's Amazon. Or, like, you can cut out the middleman entirely and just buy directly from the label (at standard retail markup, plus shipping).

I'm saying that fewer record stores anywhere -- but especially in the biggest city in the country -- means a less vital, less important Record Store Day. And once the Record Store Day numbers start to drop ... well, there are lots of things "Vinyl Mania Can't Save."

I'm saying that the statistics indicate that we've reached peak vinyl. The market will not grow much from here. It could and almost certainly will get a little bit smaller. Fewer stores offering a reduced selection at higher prices? It could get a lot smaller.

I'm saying it's not just one thing, but it's never just one thing.

You'll be heartened to know that the country's biggest vinyl retailers -- Amazon, Urban Outfitters, Hot Topic, etc. -- won't really be affected by any of this; they can reassign floor and warehouse space with relative ease, and phase out vinyl entirely if it ceases to be a value proposition. The major labels will also emerge unscathed; after all, vinyl represents only a tiny fraction of their total revenue. In fact, the only people who will be totally screwed over here are (in no particular order):

- The independent record stores who are bled dry by these price hikes and policy shifts.

- The independent labels who actually rely on vinyl sales revenue to keep the lights on.

- The independent vinyl-pressing plant owners who will see their orders drop as independent record stores go out of business.

Over time, the steady conflation of these factors will probably reach a tipping point, resulting in mass losses almost instantaneously ... but who knows? Maybe it's sustainable! Maybe all these disparate elements will find a balance! Maybe all these downward trends will reverse!

And maybe you see it differently. Maybe you see AdWeek telling you "how brands are capitalizing on music's most analog medium," how "vinyl sales have steadily grown over the last decade," and in that, you see some potential. Maybe you see an opportunity. Maybe you do! Me, though ... man, I don't see it at all. I look at all this and all I see is a crisis.