For All The Fucked-Up Children Of This World We Give You: Beach Slang

In the lobby of Philadelphia's Hilton Garden Inn, Charlie Lowe, Beach Slang's tour manager, leans over and adjusts frontman James Alex's bowtie. Alex lives an hour away in the suburbs with his wife and infant son, but tomorrow Beach Slang will fly out for a European tour, so the band decided it would easiest for everyone to just meet in the city. In a few minutes, Alex and the rest of Beach Slang will head over to the nearby Reading Terminal Market -- filled with a decadent collection of cheese, meat, and brownies the size of an infant's head -- for a photo shoot, so the superhero's costume must be perfect.

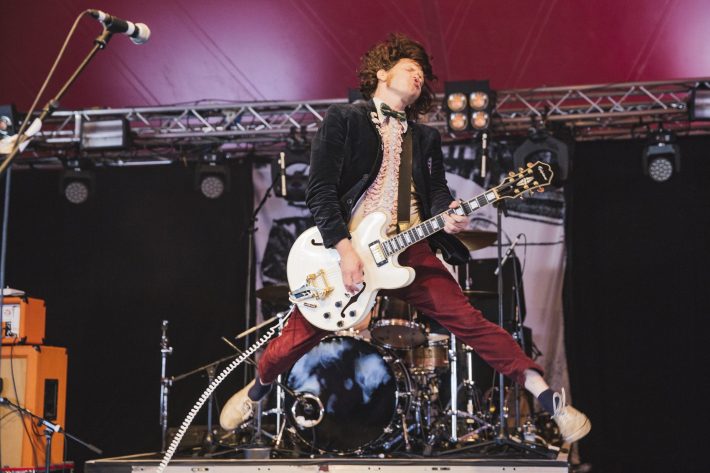

Alex is wearing a light pink ruffled shirt and a blue blazer covered in buttons -- there's one for the Replacements and one declaring "I Like Kissing," which is either just useful information or emblematic of fandom for a band I haven't heard of -- and emblazoned with a patch trumpeting "Teenage Feelings." As always, he is wearing merlot-colored pants (he owns three pairs). I'll later ask him if the outfit, which he has worn for every press photo he has taken in support of Beach Slang's sophomore album, A Loud Bash Of Teenage Feelings, is supposed to invoke prom night, the most teenage-feeling-fueled event of all, but he denies this. (He bought the shirt and fancy bow tie at London's Camden Market. "Life's getting better," Alex tells me. "I'm celebrating. It's an evolved version of the look.") His appearance fits the overall theme of the album so adroitly that I briefly wondered if Alex was just blowing off the question. I would later learn that Alex is constitutionally incapable of such an action.

I first met Alex a year ago at Drexel University's college radio station, when I went to Philadelphia for a piece about how the city had become the center of American rock music. Beach Slang were several weeks away from recording the 10 songs that would make up their open-hearted and overdriven breakthrough debut The Things We Do To Find People Who Feel Like Us, but Alex's look was already coming together. By the time the album was released, it had coalesced into a standard uniform of dark red pants ("I've never worn jeans in my life," he says. "I don't know that I can pull it off"), and blue blazer atop a gray sweater vest, sometimes augmented with a baseball cap. The effect was very reminiscent of AC/DC's Angus Young and Cheap Trick's Rick Nielsen, rock 'n' roll's most prominent eternal school boys.

Alex wore this outfit in every press photo, video, and live show in which the band participated in support of Things. It became such an instantly recognizable image, at least in some circles of internet music fandom, that when I first met Alex for this interview and saw him wearing a black Big Star hoodie and a denim vest, adorned with buttons repping the Replacements, Jawbreaker and Psychedelic Furs (lest you worry that he was going completely off-brand), it somehow felt wrong to me, like spotting Lady Gaga in baggy sweatpants and a ratty T-shirt.

"My mom was really into the Beach Boys and the Beatles, and they always had that sort of Buddy Holly thing. And I think that stuck from an early age, her showing me old clips of stuff like that," he says of his stage clothes. "I've always been kind of shy-ish. So I feel like when I put that on, it's got a little bit of a Clark Kent-to-Superman vibe. It gives me some sort of bravado that I missed. Because then when I take that off and get back into my street clothes, I'm just sitting in the corner with a book again."

More than any young band currently working in the American rock underground, Beach Slang take on a larger-than-life persona in their work and turn tales of being wasted, heartbroken, and beaten down by life -- and finding salvation in music -- into the stuff of myth. Like Bruce Springsteen, Brian Wilson, and many other songwriters before him, Alex uses adolescence as a platonic ideal that he can continually mine for inspiration. "Every time I write songs, I just imagine I'm scoring a John Hughes film," he says.

This helps explain why Alex, who is 42, and his bandmates -- guitarist Ruben Gallego, 27, and bassist Ed McNulty, 26 -- can get away with titling an album A Loud Bash Of Teenage Feelings, and having several songs chronicling the pains of "nothing kids," "fucked-up kids," and "hard-luck kids." With his long, lanky body, lean, boyish face, and tendency to use Happy Days-era slang terms in conversation like "talk turkey," "noogies," and "smooching," there's something fittingly and elementally teenage about Alex. Before he took a break to get changed for the photo shoot and before his bandmates joined us, we sat and talked for a while in the lobby of the Hilton. For the record, he's very aware of the fact that he's not a kid anymore.

"I don't know if I ever was, man," Alex says. "I was forced to grow up pretty quickly."

He was born James Alex Snyder in Middletown, RI to a Navy gunner who left when he was a year-and-a-half old, shortly after the birth of his brother. "I never call him my dad," he says. "I call him my birth father." He never had a relationship with said birth father, and shortly after that man's death two years ago, Alex legally changed his name to James Alex. "I immediately felt like I was just cutting off a bad scar," he says of lopping off the surname. "I just wanted to get rid of it."

Without his dad around, "My mom would have to work two or three jobs. So through no fault of her own, I was just passed around for people to take care of me. It was random, whoever could sort of fill the hole. And ... a handful of those people were not very nice."

He trails off for a second.

"So yeah, I was forced to be a little man pretty young."

Alex looks out the hotel window, his shaggy hair covering most of his face. He starts gently pressing his palm into the table.

"I'm trying to get the courage to talk about it more openly," he says. "Someday."

"You don't have to talk about anything that you don't feel like," I reply.

"Yeah. Yeah. Maybe it helps someone," he says. "I just don't want to look like I'm playing that card to try to make the band more interesting."

"I understand."

"That's absolutely where it stems from, though," he continues. "No doubt about it. That stuff really gets seared into you."

Eventually, Alex, his brother, and his mother moved to Lehigh Valley, PA, "just outside of Philly," to be near his grandparents. He describes himself as a "pretty introverted, wallflower-y" teenager, "more an observer than a participant." He lost himself in books and records, and through the skater culture of New England he had already gotten hooked on "the Buzzcocks, Circle Jerks, D.O.A., all that kind of stuff," he says. "But in the Valley, that was the first time that I got introduced to the scene."

He started frequenting record stores and DIY shows religiously, eventually becoming obsessed with a local punk group called Weston. "I just thought they were the greatest band in the world. I would travel all over to see them. And then when their guitarist was going to split, they said, 'Look, you're at all the shows. Is there any way you would want to play?' They never heard me sing, they never heard me play guitar, they were just like, 'We like you.'"

Alex had been practicing guitar since he was 13, and fortunately, "the songs weren't incredibly difficult. I was OK at the time. Enough to knock through it."

He joined in 1994, just before the recording of Weston's debut album, A Real Life Story Of Teenage Rebellion. By the time of 1996's Got Beat Up, he was regularly taking lead vocals on songs. The band was relatively notorious for high-energy, unapologetically goofy live shows that often devolved into public underwear parties. "We were very honest with who we were at the time," he says. "We were kids just being dumb and goofy and having the time of our lives." Though they never became hugely popular, they are still beloved amongst pop-punk aficionados. (When I interviewed the comedian and talk-show host Chris Gethard for a piece recently, he told me that when Beach Slang played his show this year, he and several of his friends cornered Alex and talked his ear off about Weston for 10 minutes straight.)

During the post-Blink-182 and Green Day Warped Tour gold rush, Weston signed with Mojo, a subsidiary of Universal Records best known for bringing the world ska-punk hitmakers Goldfinger and Reel Big Fish. In 2000, Weston released their fourth album, The Massed Albert Sounds. They would break up on tour a year later.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=XetCQSG_JCg[/videoembed]

"Not to talk turkey, but I think the best Weston ever was, was when we surrounded ourselves with our friends and people we loved and trusted," he says. "I think we just made decisions that we pretty quickly realized were just not right for us. It just felt wrong. We were really unhappy. We felt like the thing got out of our control a little bit."

Burned out by near-constant touring and dejected by the fan response to their album, which saw them move away from their signature pop-punk sound to more traditional radio-friendly alt-rock, the band called it quits a few minutes before playing a show. "We said to ourselves, do we want to be a band? Or do we want to be friends?" Alex says. "And we looked at each other. 'How about we stay friends for the rest of our lives? Let's end this thing.'"

Alex is happy to report that the band members have all remained close, and have played a number of reunion shows. There was talk of making another album, but it never came to fruition. He would occasionally play open-mics and tried his hand at a number of recording projects, which he dismisses now as "just an intellectual exercise." He kept writing songs, but he says that for several years after Weston, he assumed that he was done playing music in any significant fashion, and struggled to find a direction in life. "I was just being a wild one. I felt like a lost little floater," he says. "There's only so many drinks and drugs and smooching you can do before you're like, 'Man, I need to find something that has a sense of permanence and realness to it.' And then when that doesn't come, you start to feel like, 'What's the point?'

"Once Weston ended, I was trying to figure out, what do I do now?," he says. "I only identify myself as this guy who jumps around in his underwear and plays songs."

After the photo shoot ends, Alex, Gallego, McNulty and I gather in the computer lab/business center of the Hilton and close the door. Shortly afterwards, for about 10 minutes in our conversation, a middle-aged man walks in, tries to print something, grunts, and slams the computer. We all try to ignore this.

After a few lost years, Alex met his wife Rachel at an indie rock dance party in 2005 while he was visiting Philadelphia. They began writing each other, and she encouraged him to move to the city and enroll in art school. Eventually, he scored a graphic design job with the branding company 160over90. (Alex designs all of Beach Slang's album covers and merchandise, citing Wes Anderson, the Smiths, skateboard culture photographer Craig R. Stecyk, and documentary photographer Mary Ellen Mark as his main inspirations.)

He was happy. Or as happy as he could be without music.

For a few Weston reunion shows for which the original drummer was unavailable, the band recruited a local musician named JP Flexner to fill in. Flexner knew that Alex was continuing to write songs, and Flexner pushed Alex to record them, recruiting McNulty, who had been playing in bands since he was a teenager and who booked one of Flexner's other bands at a house show, to play bass. The result of those sessions was Beach Slang's four-song debut EP, Who Would Ever Want Anything So Broken?, released early in 2014.

"I didn't protect myself. I just sort of bared it all," Alex says of the songs. "If you think this is too earnest, too corny, or whatever, I don't care. It's what I want to do. I finally hit on writing something really pure."

The response to raw, rousing anthems like "Filthy Luck" and "Punk Or Lust" was immediate. After their debut show at Philadelphia's now-defunct Golden Tea House, they played the emo-oriented Brooklyn DIY spot Suburbia. "We started playing, and immediately, everyone was singing. I mean, hearts out, eyes closed, fists in the air," Alex says. "I remember we were looking at each other on the stage, our mouths open. We really had a moment of disbelief. When I first came up, the internet wasn't a thing. We left there floored."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=2SJ-aR4VqXI[/videoembed]

This came as a great surprise to Alex, who viewed the project as a one-off deal. "My expectations were literally none," he says. Right after the EP's release he moved to California for a graphic design job. But the EP continued to sell, particularly via Bandcamp, and various media outlets began writing about the band. He could sense the momentum. "I didn't want to have the conversation later in life, where I went, 'Man, I wish we would have seen that thing through.' So I moved back home. And then we started to get a little more of a sense of, 'I think we're a band here. Not just this little project to record James' songs.'"

A second EP, Cheap Thrills On A Dead End Street, followed in September, upping Beach Slang's exposure even more. They celebrated with a run of CMJ gigs in New York. Even before the release of a proper album, their popularity and profile had already far exceeded that of Weston. "James has become a much more mature songwriter and a much better player than he ever was," says Bruce Warren, assistant station manager for WXPN, Philadelphia's listener-supported radio station. He's been following Alex's career since the days of Got Beat Up. "You know that expression, a good wine sometimes ages really well? I think that applies here."

Beach Slang were doing small regional outings, but in 2015 they were offered a five-week long tour opening for Cursive. It would be their first national trek. "[Day-job employer] 160 gave me the, 'We love you, but we're at the fork in the road' talk," Alex says. "'Are you with us in your designing or are you going to chase this thing?'

"I said 'I'm going to chase this thing.' That was a very pivotal time for Beach Slang," he says. "It was an easy decision to make, but that didn't make it any less scary. 'Am I going to be able to send enough money home?'"

Alex quit his job while his wife, who works as a physical therapist, was pregnant with their son Oliver. "She's real pure in her support," he says. "Remember when Adrian wakes up from that coma in Rocky, and she's like, 'Did Rocky win?' She's like that. She said, 'I don't want a shadow or a shell of who you are. I knew what I was getting into when I married you.' She's a better person than I am. That's a really tough dive to take."

For their early shows, Beach Slang would recruit friends to help out on guitar, but for the Cursive tour they recruited a full-time second guitarist, Ruben Gallego, a Florida native who moved to Philadelphia with his band Rescuer in 2009. "I've always known that this is what I wanted to do," says Gallego, noting that he barely knew his band members when he decided to move and ended up leaving the group shortly afterward, but was glad to end up in Philadelphia anyway. "It was always about making it easier on myself. And if that meant finding the cheapest rent and then living in a shithole just to be able to tour, then that makes sense."

Alex is a decade and a half older than his bandmates, but McNulty says, "We don't think about it." For his part, Alex insists, "Maturity-wise and stuff, we all sort of rest in the same place." The band members have roughly similar tastes, with Alex hipping them to bands not previously on their radar, such as the Magnetic Fields, though he has his own blind spots as well. Even though Weston toured with them, Alex isn't as familiar with the recorded works of AFI as his bandmates are.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=i7nXvOTqyCY[/videoembed]

Last fall, the band released its full-length The Things We Do To Find People Who Feel Like Us, an unapologetically earnest tribute to the Replacements, the Smiths, and any other band that got college radio and mixtape rotation in the '80s. Knowing full-well that sometimes subtle doesn't get the damn job done, this was an album by made artists with the courage to go far over-the-top in their portraits of feeling eternally broken on the inside but alive when the right song plays. Lyrics like: "If rock 'n' roll is dead again/ How come I can't stop listening?" practically dare the non-believers to roll their eyes, but for people who love the drama of rock 'n' roll and just don't have the energy to debate its current relevance anymore, the album was almost pornographic in its eagerness to please.

"I think James is able to pull from Replacements, Hüsker Dü, Psychedelic Furs, etc. and not come off as nostalgia or tribute, maybe because he has the distance to understand what was special about how that music felt to listeners when it came out," says Hold Steady singer Craig Finn, a fan since the second EP and a man who knows something about finding unexpected success with a second band. "Somehow he taps into the feeling that those bands in the '80s gave to the people who were into them. A connection to other misguided souls or something like that. With Beach Slang, he's able to make you feel a part of something bigger. That is what is so exciting about it."

"We're Beach Slang and we're here to punch you right in the heart."

So began every Beach Slang performance of the past year, right before the band launched into a set that's almost absurdly crowd pleasing, Alex playing with a vigor that puts frontmen half his age to shame, thanking the crowd between every single song and capping each night with an encore stuffed with chestnuts by Guided By Voices, Jawbreaker, and several (perhaps too many) selections from the Replacements songbook. I saw them twice in support of Things, and I don't think I've ever seen someone so damn happy to be on stage, so clearly grateful that anyone cares at all about what he does, still shocked that he got a second chance.

Which made it very surprising and dismaying this April when word started traveling by Twitter that the band had broken up onstage at Salt Lake City's Kilby Court. As Stereogum reported at the time:

James Alex repeatedly announced that it would be their last show and told the crowd they should be given a refund. The tension reportedly came to a head at the end of the set, when Beach Slang attempted to cover "Can't Hardly Wait" by their spiritual ancestors the Replacements and ended up imploding in Replacements-like fashion. According to multiple fan reports, Ruben Gallego threw his guitar down and stormed off stage, after which Alex announced again that this was Beach Slang's last show, slammed his guitar into the stage, and walked off.

The show ended with Alex stating: "We were Beach Slang. Thank you. Natalie, give them their money back." But the next morning, Alex quickly announced on Facebook that the band would in fact not be breaking up, stating, "If you're still in, we are." A few months later, the band announced that Flexner had left the band. (Flexner did not respond to a request for comment.)

Alex winces when I tell him that it looked like he was following the Replacements playbook a little too closely that night. He doesn't want to go into great detail ("I love him as a person"), and says he'll always be grateful that Flexner pushed him to record the first EP, but he admits there was a personality clash. (For the record, and I only state this because it's the sort of cliché that one instantly assumes in situations of this nature, Alex made it clear that substance abuse was not the problem.)

"We had had several talks with him. 'Hey, look man, here's A, B, and C that's just proven problematic,'" Alex says. "'How do we fix those, and are you interested in fixing those?' We really tried to do everything we could to keep him. But it was a serious backslide. We tried to make it work. We just came to the realization that it was never going to work."

The tensions came to a head at the Salt Lake City show, "after a very, very specific thing happened that night with JP," Alex says. "My heart got shattered five minutes before we played. And I immaturely, wildly failed at processing those things. What I should have done was just gone on stage 15 minutes later, talked to somebody I felt like I could have talked to, and tried to process it enough to at least get through the show. I didn't do that, right? So things were as raw as they could possibly be. For better or for worse, the flag I fly with Beach Slang is my heart on my sleeve. Honesty isn't always bunnies and rainbows. Sometimes it's bruises and cuts."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=xBjgsWEaI6E[/videoembed]

Beach Slang has had Cursive/Okkervil River drummer Cully Symington, and Arik Dayan, from Gallego's former band Rescuer, play with them on tour, and they hope to hire a full-time drummer at some point in the future. Now that the band, by all accounts, is currently running smoother than it ever has (Alex says that both of the fill-in drummers already feel "like one of us"), Alex is thankful that the breakup made him realize something had to change. "That's where we started to make the most concrete steps. Don't put a Band-Aid on a broken leg. Fix the break." But in the moment, he truly believed Beach Slang were over.

"I'm walking down this alley, back to the hotel. And this girl comes running down, probably a couple of football fields away at that point. And she just grabs me and hugs me," he remembers. "Really tightly. Really sincerely. And she said, 'Please don't leave. We need you.'"

"It's weird to feel worthless your whole life, and then all of a sudden have somebody tell you, 'We need you,'" he says. "That really snapped me into shape. Because then all of a sudden I just felt like a brat."

Gallego said that the day of the incident, "I remember even before that show, stringing the guitar, James walked in the room. And he seemed fine, but I could tell something was up." The next day was rough, "but as things started to clear themselves up and I started to make sense about what happened, I was like, 'I can't be mad at you.'"

McNulty, who says that he and Gallego "bicker and yell at each other all day, and then we're laughing at each other by the end," says he was thrown off guard by the media attention. "Wow, Spin thinks this is worth talking about? We lose sight of where we're at as a band," he says. "But after Salt Lake City, James held himself accountable. And that's why I think the three of us are so strong now, especially moving forward."

Partly out of a desire to make up for lost time, and partly out of a desire "to make sure nothing grows stale," Alex says it is important to him that Beach Slang release a new album every year. "We're a rock 'n' roll band. There's really two things we do. We make records and we tour. I don't want to fail at either one of those," he says. (He also points out that a larger catalog will allow Beach Slang to tone down the amount of covers they play live in order to fill out the set list.) His label Polyvinyl told him the band could tour on Things for 18 to 24 months, "but that felt horrible to me."

Alex writes every single day, usually at night, as he never gets more than three hours of sleep or so, though he's mastered the art of getting a quick nap nearly anywhere. He wrote the songs for Feelings in hotels and green rooms, "tapping into a Kerouac, poet-troubadour vibe," recording them acoustically on GarageBand, then later teaching them to the band. "I think we rehearsed them three times." During a break in their tour schedule, they slammed it out in nine days, again working with producer Dave Downham, again employing a "two takes, max" approach. "We don't want to massage the life out of it."

Though unexpected things happen every single day, it's rather difficult to imagine Beach Slang, classicists to their core, ever working with Brian Eno, experimenting with dubstep, or having a "difficult" phase. It will surprise no one to learn that A Loud Bash Of Teenage Feelings is a refinement of the Beach Slang sound, not a reinvention, hitting the same pleasure centers as last time, but with even more force, the dramatic highs rising even higher, every chorus structured for maximum audience fist-pounding.

The main difference between the two albums is a change in viewpoint. Alex describes Things as "two-minute ballads about me and my friends coming up," whereas the new one is "narratives through the eyes of people that I've met who got turned onto the band from the first album." Alex says fans constantly write him and approach him after shows to tell him their stories.

"It's a very cyclical sort of thing, where I could see myself in them," he says. "I sort of invite it. I've offered my phone number at shows from the stage saying look, 'if you're on the ledge, call me. Let me talk you off.'" Of the stories he's heard, he says that, "typically, the heavier things stood out. 'My dad just died, and I played the record,' or 'I tried to take my life and when I came to, I was listening to your records, and they reminded me why it's important to stick around.'"

For better or for worse, the flag I fly with Beach Slang is my heart on my sleeve. Honesty isn't always bunnies and rainbows. Sometimes it's bruises and cuts.

Though McNulty says he went to a high school devoid of cliques and thus "didn't get the proper high school experience," Gallego can also relate to tales of a rough childhood. He grew up with what he calls extremely strict, conservative parents (his mother was a police officer), who wouldn't let him hang out with friends. "I wasn't really allowed to do anything," he says. "I was pretty much only allowed to hang out front of my house." He ran away from home when he was 16 while his parents were divorcing. He was homeless for a while, bouncing around friends' houses and warehouses until finally moving to Philadelphia. He's since reconciled with his family. "I don't blame my parents for how they raised me. They were just doing what they thought was best," he says. "I can't imagine having a kid at 19."

Many writers believe that writing about other people is really just another way to ultimately write about yourself. Feelings' lead single, the Cheap Trick-inspired "Punks In A Disco Bar," is a song, Alex says, "about misplacement and feeling like an outcast. When you feel unloved by the people who are supposed to love you unconditionally. When that doesn't exist, where the fuck do you belong?," he says. He pauses for a second and then shrugs. "It's about my dad. It's always about my fucking dad. He's got a weird, crummy, magnetic pull on me."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=1O1s1JbBKjE[/videoembed]

One of the reasons Alex is so capable of channeling the larger-than-life, every-moment-matters emotion of being a teenager is that, he says, he's never been able to put his childhood pain behind him. When he sings of being a "nothing kid" and a "bastard line in no one's song," he's not looking back on his youth. It's how he actively still feels in the present. "It's probably not the healthiest thing. But I keep it alive."

He's says he's grateful for the band's success, "but it came to me so late in life. So for 40 years, I've been kicked," he says. "If I have a good two or three years, there's still so much just crumminess that will ever go away. Life can get better, but certain scars never really heal."

While the first album was filled with references to being alive and making every second count, he's become preoccupied with death recently, partly, he says, due to getting into his 40s and becoming a father; one of the first lines on the album is: "I hope I never die."

His bandmates confirm this new preoccupation. "Right before the first album came out, he was like, 'God, I hope I don't die,'" McNulty says. "He said it a few times."

Alex says he recently looked at how many times he talked about dying on this album versus being alive on the first, and was struck "by the weird balance of it," he says. "Life is so fucking awesome now that that's when they're going to pull the rug out from under me."

"But to be fair, I didn't think I'd hang around this long," he adds. "Death, to me, never scared me because I didn't really care if I was alive."

Wanting to make sure I understood him correctly, I ask Alex if there was a time in what he calls his lost years where he was suicidal. The room goes quiet for a while.

"God, I feel so dumb talking about it," he says. "I feel so weak saying this. ... No. Beach Slang is about honesty," he insists. "I hope it helps. But yeah, I have. I'm glad I failed at yet another thing, so I can be here to tell the tale. I think that's the voice I try to give to things now. I'm telling you, I was literally there. And you can punch through it. I know you're tough enough."

He smiles again. Eventually, we start talking about the ways the band has bonded on tour; surfing and playing with koalas in Australia, renting scooters in Amsterdam. He's trying to make every moment count now. If he can't let go of the pain of his past, if he just doesn't know how to, he can at least put some great memories alongside it.

"I don't want to sound like a sad luck story. Oliver... I can't not smile when I'm around that kid, because he's just amazing. Rachel's awesome. I have such wonderful things. However, there will always be a part of me that... I just won't let go of the junk. Because I need it to do work that I think matters," he says. "Because through that, I wrote some things that maybe mattered to someone.

"So maybe, with any luck, I'll feel like a loser for the rest of my life."