You can more or less divide R.E.M.'s career into three chapters. There's the five-album run beginning with 1983's Murmur and ending with 1987's Document, the near-unimpeachable stretch on I.R.S. Records when R.E.M. established their immediately identifiable, jangly college-rock sound. Then 1988's Green came out on Warner Bros., and the band began their ascension into full-blown pop stars, with albums like 1991's Out Of Time and 1992's Automatic For The People spawning major radio hits. Then there was the final act, the winding and searching path the group took from the late '90s through to their dissolution in 2011, an era that saw them experimenting with their sound on overlooked gems like 1999's Up and 2001's Reveal, and making halfway back-to-basics moves on 2008's Accelerate and 2011's Collapse Into Now. To some, those I.R.S. years remain the definitive phase of their career. Others prize the years where R.E.M. truly broke through into the mainstream, finding personal resonance in the band's series of weird-kid anthems attaining wider success. Few rank the third chapter as anything close to a contender to the preceding two, which is hard to argue with even while R.E.M.'s latter records range from wrongfully maligned to severely under-appreciated. Everything that happened in that third chapter can, in some fashion, be traced back to one album of R.E.M.'s '90s prominence in particular: New Adventures In Hi-Fi, the record they released 20 years ago tomorrow.

Despite its title, New Adventures In Hi-Fi is an album marking the end of things. Paired with Monster, it closes one phase of R.E.M.'s career. In a moment not dissimilar from what happened when David Bowie dabbled in new wave on Let's Dance, R.E.M. had joined the Alt Nation groups they'd inspired -- cribbing some of their grunge aesthetic on Monster, but generally bringing a more cerebral, artsy, and moody ethos to the mainstream before that, too. New Adventures was plenty successful at the time of its release, but hasn't been canonized in the same way as Automatic or Murmur. With the hindsight knowledge that its followup was the subdued, electronic-leaning Up, you can look back on it as the end of R.E.M.'s time as major celebrities and hitmakers, even though they generated a handful of pretty recognizable songs in the '00s, too. On some level, none of this matters in their narrative. Once upon a time, maybe New Adventures could've been looked upon as the transition between R.E.M.'s big pop records and the experimental albums that followed, not as an end note signaling the border between two different chapters. But Bill Berry left the band after New Adventures, meaning the album now stands not only as the end of one chunk of time in R.E.M.'s lifeline, but of R.E.M. as we knew them.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Berry was R.E.M.'s drummer, and one of the band's founding members, alongside Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills. His departure, though amicable, is figured by some fans as a catastrophic moment in the band's history. R.E.M. were one of those bands where each of its four members was a crucial part of the equation. One leaving, or dying, left impossible ripple effects. How many groups can you really say that about? Where the exact interplay of these four individuals created some specific alchemy that couldn't be replicated in any other variation? That puts them up there with the Beatles and Led Zeppelin; out of their contemporaries, it's another parallel between them and U2. You need Stipe's vocal style, you need Buck's chiming arpeggios, you need Mills' bass lines and backing vocals, you need Berry grounding it all. The narrative was written from there: R.E.M.'s output got a bit more inconsistent after Berry left, it was the "three-legged dog" phase. It was too easy to say the loss of their drummer literally unmoored the band, that anything from the post-Berry years was one long sigh of an epilogue for a catalog otherwise filled with classic albums wall-to-wall. So, in turn, it lends New Adventures a certain weight: It is the would-be swan song that, chronologically, sits in the middle of the band's career.

But New Adventures isn't a complete misnomer. This was the record where R.E.M. explored new methods and broke new ground. Famously, the band recorded New Adventures mostly in transit, taking a cue from their newfound pals in Radiohead and cutting tracks during soundchecks and rehearsals while on their troubled tour behind Monster. The material was later cleaned up a bit (and a few songs were cut in the studio), so it doesn't sound like a live record, exactly, though it does have a full-bodied rawness in places that makes sense when you know how it was crafted. The result was an album that rushes by, grasping at different cities and people and moments, and them occasionally staggers into worn, out-of-breath moments.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

There's a version of R.E.M. where one of their greatest strengths was their visceral sense of concision. In that context, New Adventures had a distinctly un-R.E.M. quality to it. It remains their most sprawling record, wheezing and gasping past the hour mark. The songs flit between various sounds and tones. Given that and its in-motion inception, it can sound shambolic. But it's one of those big, shaggy records that holds together remarkably well as a complete work: a document of a band at one peak of their powers, summarizing many of the things they did well while also gesturing at previously unexplored places.

On one hand, you had stuff that was solidly in their wheelhouse. "Bittersweet Me" is a wizened version of a classic '80s R.E.M. song that never was. "Departure" is the big, evocative alt-rock pop track. "New Test Leper" and "E-Bow The Letter" were grainy in a different way than the group had ever been before, but they were also descendants of some of the material on Out Of Time and Automatic For The People. These songs sat alongside material that more directly exposed a darkness and tension at the heart of the record. "Leave" comes across like the swirling black core at the album's center, a seven-minute spiral of anxiety and hypnosis alike, riding along that weird interplay between one guitar that sounds like a saw warped and stuck in a loop and the mourning lead line. Though there are detours along the way, "Leave" sets the stage for the album's ragged final act. "Be Mine" is a romantic song, but the kind that sounds cripplingly sad if you're in a certain spot when you listen to it, while "So Fast, So Numb" and "Low Desert" stacked near each other at the end of the record give you the sense of the wheels coming off of something -- a record, a band, your life, whatever.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Across their catalog, R.E.M. had a gift for openers, and for accompanying them with second tracks that erased the notion that any other song would've made sense after that first one. New Adventures has one of their best (and most whiplash-inducing) one-two pairings: "How The West Was Won And Where It Got Us" into "The Wake-Up Bomb." There are few songs in R.E.M.'s catalog that sound anything like "How The West Was Won..." It's a lounge song from the wasteland. Built on loping, off-kilter rhythms and jittery piano alongside little sun-fried guitar lines, it's a haggard opening for a haggard record. It's also gorgeous. Then it drops you right into the organ-drenched glam crunch of "The Wake-Up Bomb," a very Monster song that is better than anything on Monster and half-suggests what that album could've been. They're shuddering on the opening track, and roaring again on its second cut. The counterpoint between the two sums up the duality of the album. This was the album where R.E.M. sounded depleted and invigorated in equal measure. It's the sound of the end of a road where you can just start to glimpse an alternate route on the horizon.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

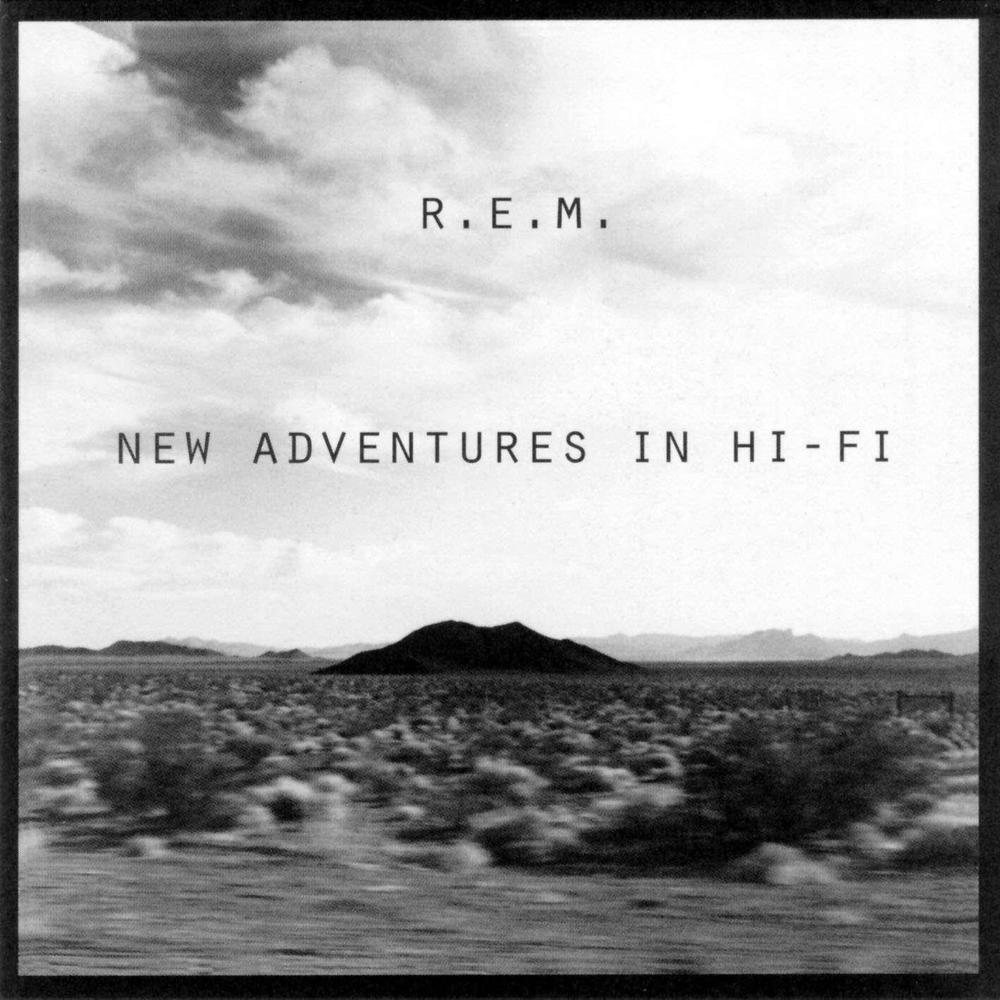

This split identity is rooted, inevitably, in New Adventures being a road album. But it's also rooted in the specifics of those exact days R.E.M. spent on tour. The band members were plagued by a series of weird health scares, most famously Berry's onstage aneurysm. They were touring a big alt-rock record during a time where Stipe was writing frequently about celebrity and exposure and his exhaustion with it all. Even without pitfalls and concerns like those, tour life isn't jet-setting in most circumstances. You lose track of what day it is, of what city you're in. You barely see those cities, anyway. It's hard to disassociate the cover of New Adventures from the music therein. This is bleary-eyed road music, composed in grayscale blur.

New Adventures has that quality endemic to some art about travel. It's more about the sensation of racing through places and barely getting to engage with them, and then trying to put them together in that big shaggy collection of an album. What remains most powerful about is its mix of weariness and wonder. Stipe always had a premature gravel to his voice, the kind of voice that made you instantly believe he was wise beyond his years, and the kind of voice that made any set of words feel profound. That worked a certain way when he'd be intoning over the tight, infectious bursts Mills, Buck, and Berry crafted in the earlier days. But even on their more meditative records, R.E.M. never sounded as collectively harried as they did here. Within the autumnal haze of the I.R.S. records, those songs moved. By New Adventures, they were writing songs about movement, but with a different gravity. They were out there in America, mulling over where winning the West got us and concluding "Not far" or "Not anyplace good." Stipe's lyrics throughout the album are littered with images of being fed up, or of escape, or of not knowing what he wants.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

So, the reason it's worth the journey, the reason New Adventures still has power and resonance, is the moments where they do still find that sense of wonder, or that sense of peace. Both are intrinsic to the DNA of "Electrolite," the closer of New Adventures and one of the best songs R.E.M. ever wrote. After all the internal battles of New Adventures, "Electrolite" is the sunrise conclusion. After all the distortion and convolutions of New Adventures, "Electrolite" is the piece of simple beauty: the saloon hymn built on piano and acoustic guitar and that yearning violin, all the undercurrent to Stipe's meditative visions. After all the transience and lack of permanence of New Adventures, "Electrolite" is the shuffling wanderer song where the wanderer finds some solace, some home. Stipe tumbles surreally through Americana, and through pop culture history -- he's Martin Sheen, he's Steve McQueen, he's Jimmy Dean. The 20th century is going to sleep. And then, finally, after the maelstrom that is this album, Stipe finds his way to his last denouement: "I'm not scared, I'm outta here." He almost sing-speaks it. It's such a calm, pensive, controlled moment, but it's also one of the most powerful resolutions to an album that I've ever heard. Perhaps because it is that affirmation amidst, or after, the storm. Perhaps because even in its matter-of-factness, it sounds titanic.

As much as "Electrolite" was the world opening up on a new day, there was also a sense of finality to it. With parting words like "I'm not scared, I'm outta here," well...shit, can you imagine a greater final track for a band to release? In some ways, then, it's easy to see an alternate history that some fans would prefer, of New Adventures striking out for new vistas while being as intentional a full-stop as Collapse Into Now wound up being 15 years later. In reality, that was never the plan, as much as some people want to write the post-Berry years out of existence. The lurching, scattershot quality of R.E.M.'s final act doesn't diminish the power of New Adventures as some kind of finale, though. I'm not scared, I'm outta here -- and from there on, R.E.M. followed stranger muses, operated within some different machinery.

Over the years, this album has accrued the status of being an underrated record in a celebrated career, a lost classic of theirs and of the '90s as a whole. As rich and strange as R.E.M.'s work was often otherwise -- whether their acclaimed and canonized albums, or their unheralded left turns -- New Adventures is the one that keeps coming back and demanding it gets some greater recognition. Sure, it may nominally be a tour album. There's a stereotypical, classic-rock banality to that narrative. But filter it through Stipe's imagistic language and the dusty expanse the band conjures around it, and -- like you always did with R.E.M. -- you get something more idiosyncratic, more enduring, than the run-of-the-mill rock narrative. These were four old friends who had built something together, and found themselves reckoning with that and their lives and what they were filled with as they passed through their thirties. It's an album about movement in ways physical and abstract, spiritual and chronological. Those are the albums you take with you, the ones that will continue to reveal something new for years to come.