When Fatboy Slim showed up at the closing ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, he smashed through all the glitz and glamor of the whole show like the Kool-Aid Man bursting through a plaster wall. The whole event was an intricately choreographed, glowingly bright show of force, a kingdom putting all its pop-cultural power on full display. And yet here was this deeply nondescript middle-aged guy in a gallingly ugly short-sleeve button-up, perched in the head of a giant glowing inflatable octopus, stabbing at buttons in front of him and making "let's fucking 'ave it!" faces while his late-'90s hits echoed around a massive stadium. In the middle of a stadium, with the eyes of the world on him, Norman Cook did dances that, if you or I did them at a wedding, our friends would be making fun us for weeks afterward. It's like he'd decided to play the role of drunk uncle for an entire nation. It was ridiculous, and it was perfect.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

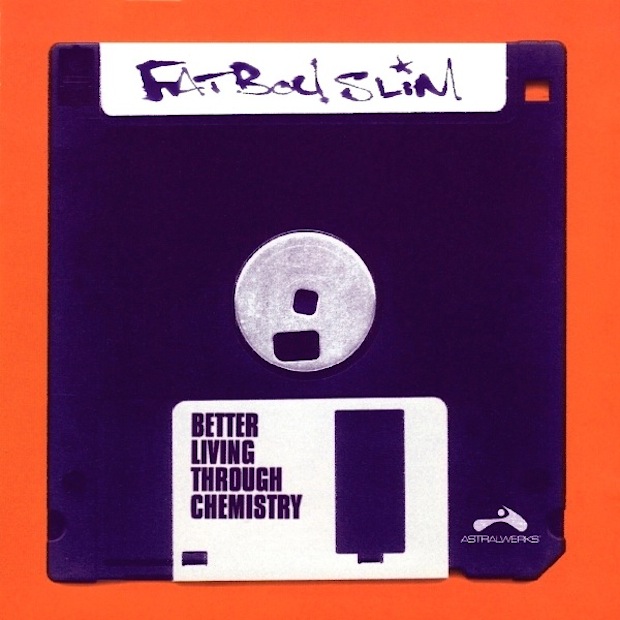

When Fatboy Slim first hit the UK dance music scene 16 years before that closing ceremony, it's easy to imagine it having the same "who the fuck is this guy?" effect. The Fatboy Slim who we met on Better Living Through Chemistry, the first album that Cook recorded under that name, was a gleeful and shameless pilferer of hooks, a good-time charlie with no use for the mystical pretensions of rave culture. He wasn't trying to transcend time or space; he was just trying to have a good time. It's not that Cook was the first person turning dance music into novelty songs. That had been happening right from the beginning, especially in the UK. (Consider LA Style's 1993 smash "James Brown Is Dead," released 13 years before the actual death of James Brown, or "Doctorin' The Tardis," which the KLF recorded under the name the Timelords and rode to a UK #1 in 1988.) But Cook was the first person to rise to dance-music stardom on the strength of novelty songs. He's the one who made novelty songs his brand.

Dance-music stardom was a relatively new thing in the mid-'90s; dance producers were essentially expected to be mysterious, anonymous forces who switched up their names every time they had a new idea for a 12". The people who did cross over did so in weird fashion. The Orb were shamanic priests, Orbital were anonymous machine-cog functionaries, and the Chemical Brothers were probably some combination of the two. The Prodigy's Liam Howlett hid behind the charismatic dancers who became his vocalists. Cook, meanwhile, seemed happy for attention, and he never really worked on inventing or obfuscating a persona. He was just a party guy who liked to find fun ways to slap old records together. A lot of the time, they were records you already knew, and he was just fine with that. His big, bright, mercenary approach to the form probably had a lot with it becoming a neon-zoo shitshow in the years to come, but it sure was fun for a while.

Cook wasn't really the Kool-Aid Man when he turned into Fatboy Slim. He'd been a known quantity in the UK for years, and he'd improbably had two different British #1 hits, both in vastly different forms. The first time, he'd been the bassist for the Housemartins, a bobby and Madchester-ish band who'd scored a 1986 #1 with a doo-woppy acapella version of Isley-Jasper-Isley's "Caravan Of Love." (The band broke up immediately afterward, and two other Housemartins went onto form the Beautiful South.) Then, in 1990, Cook ended up in the top spot again with Beats International, a sort of loose singers-and-rappers confederation that had him at the center. He scored the hit with "Dub Be Good To Me," a bubbly and infectious track that essentially worked as a mash-up of the Clash's "Guns Of Brixton" and the S.O.S. Band's "Just Be Good To Me." But Cook didn't clear any of his samples or interpolations, and he ended up bankrupt, forced to repay all the song's royalties twice over. In the years between that and Fatboy Slim, he had more projects -- Freak Power, Pizzaman, the Mighty Dub Katz -- and made more hits, all of them with that same let's-grab-whatever ethos. Fatboy Slim was just one project in a long string of them. It's just the one that stuck.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Cook and Gareth Hansome, his partner in the Mighty Dub Katz, started a club in Brighton, the British seaside tourist town, called the Boutique, and it quickly became known as the center of big beat, a dance-music subgenre that prioritized big, dumb breakbeats and bigger, dumber hooks. And Cook, as the central figure of that whole scene, had his real eureka moment in 1998, when he took a twangy Duane Eddy guitar line and a stray Lord Finesse soundbite and turned them into "The Rockafeller Skank," the song that really broke Cook and introduced him to provincial Americans like me, via the power of modern-rock radio, which would really only play dance music if it had something resembling a guitar somewhere on it. So maybe it's best to look at Better Living Through Chemistry, Cook's 1996 debut album as Fatboy Slim, as the dry run, the moment he figured it all out. But Cook's whole Fatboy Slim identity was pretty much fully formed on Better Living: The needling 303 basslines, the towering fuck-off breakbeats, the stupid-catchy vocal samples that come in at the exact right moment. He even had something like dramatic range; "The Weekend Starts Here" starts off as laid-back afghan-rug funk and never really jacks up its tempo to losing-your-mind levels. It sounds like a less-sloppy version of one of the amateurish funk instrumentals that the Beastie Boys were using as album tracks.

The song that really defined the Fatboy Slim sound (until the release of "The Rockafeller Skank," at least) was "Going Out Of My Head," which nicked the riff from the Who's "I Can't Explain" -- probably the closest thing the UK ever had to its own homegrown "Louie Louie" -- and surrounded it with gigantic drum stumbles and euphoric diva vocals. It's a big, fun, stupid, obvious song, and that would, soon enough, be the Fatboy Slim way. In the moment it was happening, I remember being stunned that someone figured out the no-shit brilliant idea to fuse cheap-kicks garage rock with cheap-kicks techno; in Cook's hands, they sounded like they were made for each other. If I'd known this innovation would lead to a couple of decades of near-intolerable car-commercial novelty hits, I might not have been so excited. But for a few years there, Fatboy Slim was the king of the smart-dumb. And by the time the smart-dumb became the dumb-dumb, he'd already scored two more UK number ones: His remix of Cornershop's "Brimful Of Asha" and his own "Praise You." He took that moment, and he used it to get big enough that he could hold down the giant-octopus slot at the London Olympics closing ceremonies. We've got to celebrate him, baby. We need to praise him like we should.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]