The 1995 edition of Lollapalooza had a lineup that, in retrospect, seems almost inconceivably cool. It had the Jesus Lizard. It had Elastica. It had Pavement, so sloppy and aloof the day I saw them that the West Virginia crowd pelted them with chunks of mud. It had Hole, performing under silvery stars and openly feuding with other bands on the bill. It had Mellow Gold/"Loser"-era Beck, gawky and unsure and not yet ready for stages that size, though he'd get there soon enough. It had Superchunk and Helium and Redman and Built To Spill, all playing over on the side stage. It had Cypress Hill, performing in front of a gigantic inflatable Buddha with a pot leaf on its belly and, at the climactic moment of their set, wheeling out a 10-foot bowl with a smoke machine inside it. As headliners, it had old underground gods Sonic Youth, opening their set, the night I saw them, with "Teenage Riot," only seven years old at that point but already a classic.

The whole show was conceived as a rebuke to the previous year -- the Smashing Pumpkins/Beastie Boys/Breeders year, the year that Nirvana were slated to headline until Kurt Cobain killed himself -- because people thought that things were getting too pop. (That 1994 lineup also seems improbably cool in retrospect, but that's '90s alt-rock culture for you. The only early Lolla lineup that has really aged poorly is 1993, the Alice In Chains/Primus/Arrested Development year, and even that had Rage Against The Machine and Tool opening the show.) In a fascinating oral history a few years ago, The Washington Post called Lollapalooza '95 "Alternative Nation's last stand." But even with all the past and future underground icons on display, the band that seized the imaginations of me and my friends when we went to that show -- the band we couldn't stop talking about on the long ride home -- was the main-stage opening band, the one that wore plaid suits and had a horn section and a guy whose entire job was to dance. Lollapalooza '95 was an ending in a lot of ways, but it was a beginning, too. It was the dawn of the Mighty Mighty Bosstones Era.

(Pavement's Bob Nastanovich, in that oral history: "The Bosstones were so pumped, and their act was so physical, it was like an aerobics class. They had outfits. They were made for that type of thing, and we just weren’t.")

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

That tour was part of a long, long dues-paying story for the Bosstones, who had been around forever by the time they finally landed their first and only big hit in 1997. They formed in 1983, when the British 2-Tone ska scene was still percolating. They didn't get around to releasing their debut album until 1989, and they got their major-label break in 1993, when nobody knew what the fuck ska was. The Bosstones were, of course, not a straight ska band; they called themselves ska-core, and they brought in little elements of '70s choogle-metal and murky white-kid funk along with the ska and the hardcore. "Someday I Suppose" got some alt-rock radio burn in 1993, and in 1995, they got a nice little cameo in the forever-classic movie Clueless, where Alicia Silverstone referred to them as "kickin'." Before any other ska band made it onto the radio, they seemed to slot in better alongside eclectic, frenetic rock bands like Fishbone or Urban Dance Squad than any of their other peers.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

But on that Lollapalooza tour, they contrasted so starkly with all the insular, gnarled underground rock around them that you can almost pinpoint it as the exact moment that kids like me decided to turn their attention to something faster and brighter and more cheerful. The Bosstones weren't exactly typical of the wave of ska-punk that would follow in the next few years. That wave was built around California bands who sounded California as fuck -- Reel Big Fish, Goldfinger -- or bands from Detroit (the Suicide Machines) and Gainesville (Less Than Jake) who also sounded California as fuck. Lead Bosstone Dicky Barrett's voice wasn't a nasal whine; it was rumbling, Lemmy-esque growl. Like many of the other Bosstones, he'd spent his formative years in Boston's notoriously violent hardcore scene. And the Bosstones' sound -- soupier and more groove-oriented than its West Coast counterpart -- was capable of transmitting emotions other than exuberance and snotty irony.

Still, the Bosstones were a living indicator of a coming thing. In their matching plaid suits, their high-kicking live show, and their instantly memorable horn-blat melodies, they presented themselves as entertainers, which made them stand out in the enforced drabness of the alt-rock landscape. And after that Lollapalooza tour, the floodgates opened. No Doubt's Tragic Kingdom. Rancid's "Time Bomb." Sublime's "Date Rape." And then Reel Big Fish and Goldfinger and Buck-O-Nine and Save Ferris and every other thing. By the time the Bosstones got around to releasing their fifth album, Let's Face It, in the spring of 1997, the runway was clear for them. All they needed was one big song, and then all the groundwork they'd laid would finally pay off.

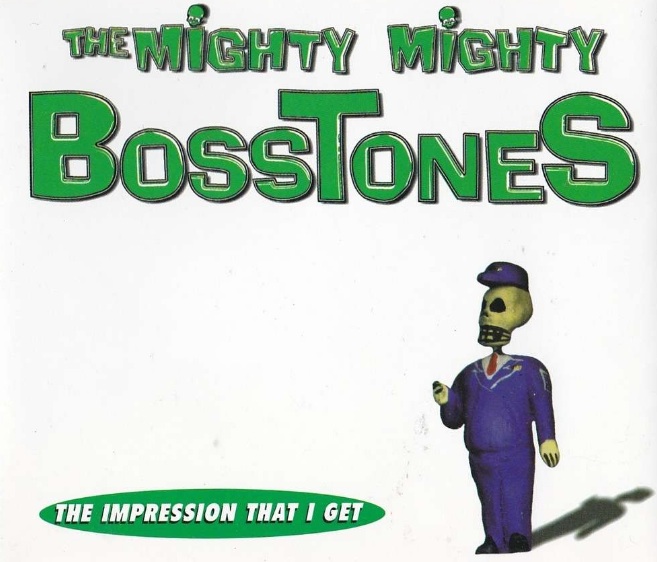

It paid off. They had that song. "The Impression That I Get," which came out 20 years ago today, was a three-minute capsule of everything the Bosstones did well. It had a needling guitar line, a horn riff that would burrow its way into your brain and stay there forever, and a huge, widescreen chorus that made for a fun big-room shout-along. The Bosstones were never exactly a lyrics-first band, and the song's message is some vague thing about how you have to wonder how you'd do when facing real hardship if that's something you've never done. The central hook -- "I never had to, knock on wood" -- always seemed nonsensical until I figured out, years later, that there was supposed to be a comma in there, but that didn't make it any less memorable. It was a fun, addictive song that did what fun, addictive songs are supposed to do. It sounded amazing for a few weeks and then became utterly maddening when you heard it too many times -- which, if you were listening to the radio in 1997, you definitely did.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

For months, "The Impression That I Get" was absolutely fucking everywhere. It was a #1 modern-rock hit that actually broke into the top 40 on the Billboard Hot 100, something that I can't imagine will ever happen with a ska song again as long as I'm alive. It showed up in Chasing Amy late enough into its cycle that half of the theater audibly groaned when it came on. The band played it on Saturday Night Live. They worked it hard. I can't even remember how many times I saw the Bosstones live in 1997. They'd always been a hard-touring band, and I imagine that they were playing multiple shows every weekend day that summer. I saw them at a radio-station festival in a football stadium, and at the Warped Tour in the the same stadium. I had tickets to see them at a vast Baltimore frat bar, with Bouncing Souls and the Pietasters opening, but it snowed that night and my parents wouldn't let me drive their car. Point is: They rode that song, and that album, and that moment, as hard as they could. And when that radio-driven ska wave petered out the next year -- dying a humiliating death at the hands of nü-metal -- the Bosstones were among the first casualties. It didn't take long before those suits stopped looking cool and became instant reminders of a vaguely embarrassing cultural moment.

The Bosstones stuck it out for a few more years, releasing one more major-label album and then another on an indie before taking an extended break. Dickie Barrett moved to Los Angeles, briefly becoming an alt-rock radio morning guy and taking a job as the announcer on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, a position he still holds down. The Bosstones got back together soon enough, touring infrequently and recording even more infrequently. History has not been especially kind to them. But fuck that. They provided a jolt of fun at a time when many of us needed it, and they wrote some great songs. (I'd argue that "Where'd You Go?" holds up even better than "The Impression That I Get," but "Where'd You Go?" wasn't the one.) I hope I get a chance to see them live again someday, I suppose.

I've only been in a band once, which should probably disqualify me from a career in music criticism, but whatever. It was during the spring of 1997, when "The Impression That I Get" was in full flower. This was an exceedingly shitty high-school punk band, and it wasn't even my exceedingly shitty high-school punk band. I didn't play or sing or help write the songs. I couldn't do any of that. I could jump around onstage like a spazz. I was good at that. We played two shows, one at a high-school talent show and another in a friend's backyard, across a river from a sewage treatment plant, a nauseating smell sweeping through every time the wind changed directions. And at both of those shows, I had a job title. I was the Dancing Bosstone. There are worse things to have on your resume.