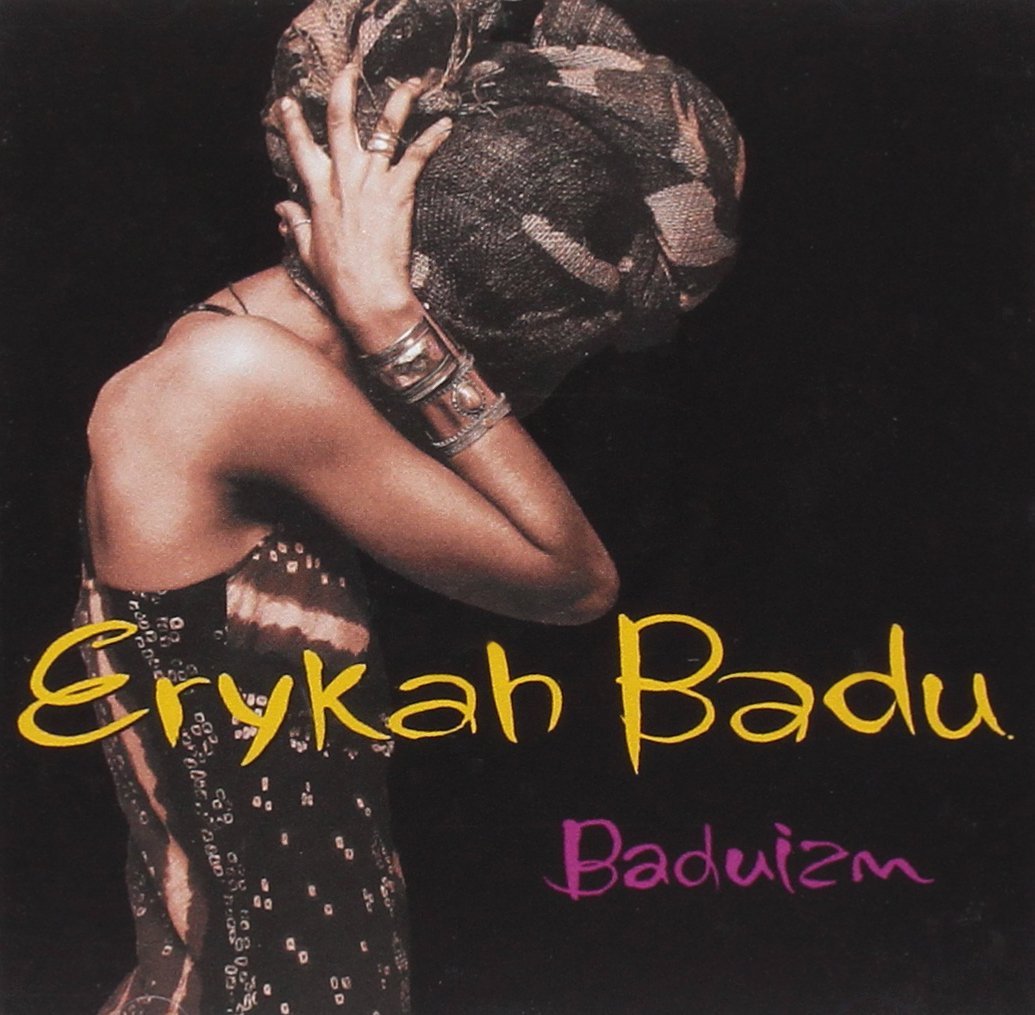

Erykah Badu was a rapper before she was a singer. You could tell. You could see it for yourself in Badu's video for her 2002 single "Love Of My Life (An Ode To Hip-Hop)," when she traded bars with MC Lyte, flattening herself up against a wall and rapping into it while she kept time with her fist. But if you were listening hard enough, it was there on Baduizm, the debut album that came out in 1997 and Changed Things. (Baduizm's 20th anniversary is tomorrow.) And even if you weren't listening hard, you could still feel it. The nods were there, like on the interlude where Badu blasted some nameless schmuck for not taking her to see Wu-Tang, or on the massive single "On & On," where Badu played around with Five Percent Nation code words ("If we were made in His image, then call us by our names / Most intellects do not believe in God, but they fear us just the same") as well as the Wu-Tang guys ever did. But it was there more in her confidence, in her conversational cadences, and in the way she just floated over her own tracks. At the time, critics praised Badu for the way she transformed R&B back into something organic and old-school. And that was an element of the appeal for sure. But there was no sweat in her music. She always sounded effortless.

When Badu arrived, she seemed to be part of the neo-soul wave, which was just then in its early stages. Baduizm came out not long after D'Angelo's Brown Sugar and Maxwell's Maxwell's Urban Hang Suite, the two albums that catalyzed a popular fascination with mystic '70s soul grooves. And she had the connections. She'd opened for D'Angelo in her Dallas hometown in 1994, and she'd gotten her record deal, in part, because of "Your Precious Love," a duet that she'd sung with D'Angelo on the High School High soundtrack in 1996. (High School High was the movie where Jon Lovitz played a teacher trying to reach his tough inner-city students, attempting to impress them by scratching up Glen Campbell's "Rhinestone Cowboy" at a school dance. It's so weird to think that a movie that ragingly inessential could've had any kind of lasting impact on popular music, but there it is.) And Badu had recorded a few demos with the Roots in Philadelphia, several of which made their way onto Baduizm. And with her trademark headwrap and her regal bearing, she seemed like the Platonic ideal of the the incense-burning take-no-shit black bohemian queen -- neo-soul personified.

But Badu had something that would last a whole lot longer than that neo-soul wave. She was not, after all, the first major-label singer to make mainstream R&B that nodded back to jazz and '70s auteurist soul. Before her, there were plenty of others: Groove Theory's Amel Larrieux, the Brand New Heavies' N'Dea Davenport, Des'ree. But Badu came across as being both harder and spacier than any of them. She could imply hip-hop and jazz at the same time without committing to either of them. She did not, for instance, have to throw a rapper on her tracks to make them feel, at least on some level, connected to rap. There were sounds in her music, like the faraway trumpet-moan on "Sometimes," that could've come from a DJ Premier track, or from Portishead's Dummy. And while every critic at the time compared her to Billie Holiday, she never let herself come off as a revivalist, either. The tone of her voice -- that tough-but-soft nasal purr -- had plenty in common with Holiday. But she used that voice to sink deep into types of groove that simply didn't exist during Holiday's era. Badu was very much a creature of her time -- and, miraculously enough, she still is.

Looking back, it's pretty amazing how an album of miasmic old-school soul music and exquisite, unhurried phrasings could be as huge as this one was. Baduizm might've had love songs, but it didn't do anything to meet the mainstream halfway. But even at the height of the Bad Boy era, it sold three million copies in the US and topped out at #2 on the Billboard 200. Badu arrived as a fully formed artist, and she still emerged as a massive pop success. In the years that followed, Badu would become a thornier artist, chasing her muse to deeper places. Her masterpiece, the sophomore album Mama's Gun, would come out three years later, and she would slowly recede from the mainstream while maintaining an absolutely singular presence in the music universe. But while Baduizm might not be as heavy as some of what Badu would go on to do, it's still a stunning piece of work, one that's aged as well as nearly any album of its era. I imagine it'll still sound amazing in another 20 years.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]