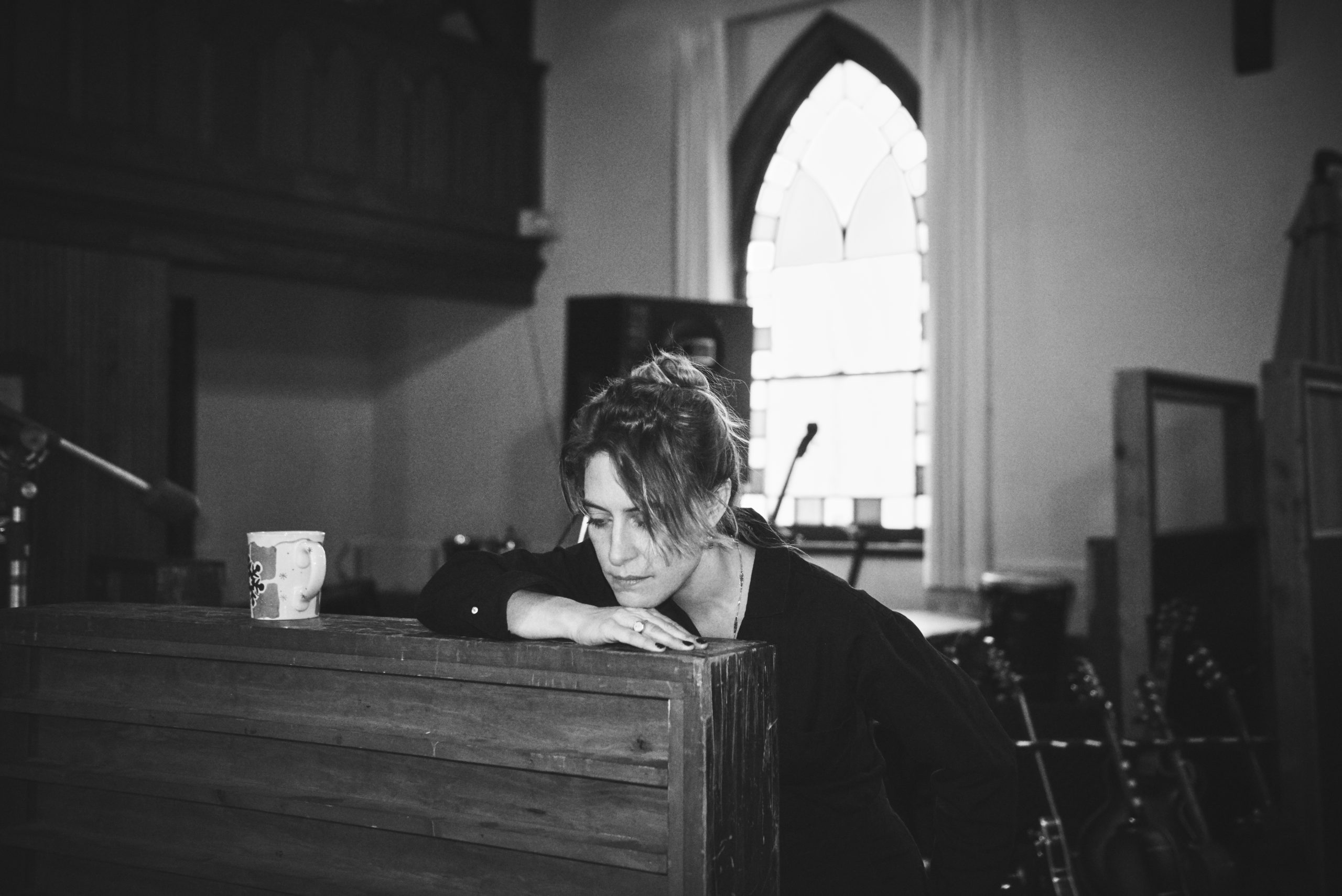

Leslie Feist has a special type of charm. She speaks with a relaxing cadence, the same way she sings on her albums, and there's an airy quality to her speech, like she could spring from her seat at any moment and begin to twirl playfully around the room. Feist's voice carries the tone of someone who prioritizes patience and kindness without acting too serious. So when she answers my Skype call from an apartment she rented in California, palm trees towering behind her while the sun blankets the rest of the back patio, she’s as easygoing as expected. “It’s my winter sojourn,” she says. “Like what you read about in the Victorian books to pass a season by the seaside.”

But as our conversation continues, Feist turns to apologies for taking a while to answer my questions. She hides her face in her hands. Pausing is a sign of proper reflection and thought-out responses, but to her, it’s a sign of unpreparedness and a new feeling. On her last four albums, Feist took calculated approaches in and out of the studio to organize her feelings, to tell her story, to create a musical theme. It’s been six years since the last release, and her upcoming fifth album, Pleasure, changes that narrative.

Though it rides on otherwise familiar Feist tricks -- warm guitar strums, whispery vocals, exclamations that burst with spirit -- Pleasure channels contemplative lo-fi; it's both rough around the edges and intentionally intimate. Most of all, the album deviates from what’s expected, be it bailing on the drum-heavy structure of 2011’s Metals or the pop choruses of 2007’s The Reminder, and Feist can’t remember why. “I tried to keep a journal while making this record because I’ve learned my memory about things can be so skewed,” she laughs. “I’m already unsure. But this album represents how many songs I wrote since Metals -- there’s no more.” By swatting away cushioned production and instrumentation pile-ons, she creates the illusion of barren demos while carefully threading them with emotional depth and spontaneity that mirrors life.

It feels entirely within her creativity realm, yet Pleasure continues to surprise over the course of its runtime. Songs actively turn their noses at smooth transitions. Her lyrics stand at a newfound distance. Feist hides her understated melancholy in samples and declarative yells, a new aspect of her songwriting acumen. At the end of “A Man Is Not His Song,” she notes that, “more than a melody's needed.” Pleasure is her answer to that: a substantive full-length that challenges people to listen for more than a pleasant melody. It’s as if by talking about it, the Canadian virtuoso realizes just how much new territory she’s standing on here, and because she doesn’t know every crevice of the land, she’s still learning how to navigate it. Still, she's filled with a palpable excitement. After a six-year gap between albums, Pleasure is the ideal place for a musician of her eminence to be, and her hesitancy to articulate it speaks to the strength of its emotional appeal. On top of discussing her new album at length, Feist and I talked about the pressures an artist faces when they're expected to grow up, and what it was like to reunite with Broken Social Scene. Read below.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: You build crescendos and extremities that aren't followed by a typical resolution on Pleasure. It’s like you’re intentionally toying with expectations. How much of that was a conscious decision?

LESLIE FEIST: My instinct is to say thank you for getting it, because you’ve summed it up well, but this is an interview so I guess you need to hear me explain that in my own words. I wasn’t sure what stories I wanted to tell in these songs. Writing songs, the presumption is that you declare something you know -- I’m trying to think of declaration songs like [starts singing Sam Cooke's "What A Wonderful World"] -- but these were ones that came free of traditional building standards. They took left turns. Like at the end of “A Man Is Not His Song” where there’s an about-face, it’s a function of telling a story where two things can be simultaneously different.

STEREOGUM: How did the break between albums play into that?

FEIST: I guess that long break [made me] want to try things. It was much more of an inward-facing decision. It had been so long since I played shows, which is the only place where I see people [except for the other artists] who worked on this record, so otherwise it feels like a figment of my imagination. Maybe it’s my upbringing, but there was no presumption that there would still be people who were curious to hear anything from me. I did this for myself, really. I think that’s the only way to approach making a record: to have a bit of humility and be a bit meek about assumptions that there are expectations on the other side. I allowed myself to tell a subtle story.

STEREOGUM: In the case of "Century," that happens after Jarvis Cocker's monologue, when the song ends by abruptly cutting your vocals. It sounds like whoever mixed it forgot to do a quick fade.

FEIST: For that [specific] ending, I wanted to feel like a director. Maybe I saw that most songs have a bow tie at the end, this type of resolution and clarity that we know something. A song like “Century,” what could you possibly know? All you know is that a single second can feel like a lifetime or a whole lifetime can pass in a flash. Time is elastic. There’s nothing to know about that except, yes, you can’t draw a conclusion. The director of a movie wouldn’t question making a quick cut; it would be a way to deepen that narrative. That was the case with the song’s ending.

STEREOGUM: There are several other surprises throughout, like a car that drives by playing the title track or a Mastodon sample. It almost sounds like you’re going on a walk, stopping in different houses, catching snippets of life, saying hello to friends whose personalities differ from yours.

FEIST: It’s funny, because the songs were written in the same period, so they point at one another a lot. Honestly, we almost finished the mix when the two guys who helped finish it suggested we listen to all the songs to see where we’re at. My instinct was to smooth things out, but then I realized what you just described -- that it created pockets of sound that appear whenever they please. To begin with “Pleasure,” the university professor 1.21 gigawatts guy at the front talking about evolution and time, to then go to a song like “Young Up” at the end -- it feels like you’re leaving a party to go somewhere better. Dawn is coming. Maybe there’s a clearer tipping into optimism.

STEREOGUM: You talk about sadness surrounding this record, but I hear a hopefulness in your songs.

FEIST: I tend to end up talking about sadness a lot in these interviews, but I think that’s a bit oversimplified. I think this album is more about optimism.

STEREOGUM: Especially ending with “Young Up.” It highlights despondency about growing old, but you also champion retaining inner youth as you age.

FEIST: Maybe this record, for me, is glancing at the place where accepting both is always going to be the case. A song like “Get Not High Get Not Low” is direct instructions to 71-year-old Leslie. I feel like these are songs are that I wrote for a version of myself that I aspire to be. I have friends that are 20 or 30 years older than me, older than my parents, who have become my buddies ... Growing up is an illusion. All that I really aspire to bring into that with me is a sense of humor. A phrase like “young up” came to me because I literally got to a point where I had become so stiff by repetition -- you get ground down by your tendencies -- and [routine] was aging me before my time.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: You said Pleasure is a study in self-awareness. Is that part of what you meant?

FEIST: Yeah. That intention, the language, the way you choose to tell your story to yourself, the voice that you let tack onto you: Is it telling you that everything sucks? You end up manifesting what you give the most attention to. You make it happen. It’s almost like every person is an alchemist or magician, because we can actually make the things we think [up happen]. I know a million books have been written about this and are usually in the self-help section, so don’t hold that against me.

STEREOGUM: If anything, that speaks to the album and this expected notion that growing up builds your confidence enough that you stop learning, that the facts you’ve learned are good enough to get you through what’s to come.

FEIST: At this point, you’ve probably had people in your life -- for however long you’ve been calling yourself an adult, from 13 or 17 or whenever -- there are people we’ve had in our lives like parents or family friends who are now that much older. To see how aging can occur allows you to see people you haven’t seen since high school become either like Benjamin Button, where they’ve gotten younger, or the opposite. It’s instructive to look forward in time to see how other people have done it. Invest in the version that looks like how you want the future to be for you.

STEREOGUM: Over the course of the album, you mention “togetherness” a lot, both romantically and platonically, as if that ties directly to pleasure. How come?

FEIST: I think it’s the multifaceted benefit you get from life, like knowing what piece of the puzzle you are. Are you sinking the ship or are you the wind in the sails? In a song like “Pleasure,” togetherness is talking about [the evolution of family], like your grandfather and your grandchild, a continuum you’re a part of. There’s a one-on-one basis, too: Are you there for your friends and are they there for you? Are you reliable? Can you rely upon yourself to comfort yourself? Sometimes I oversaturate myself with people and, in a way, I medicate myself with solitude. But solitude can lean too heavily in that direction, and when I find that the solitude isn’t positive or I’m not doing it for my own good but rather like an animal hiding in the back of its cave, then I’ll dose myself with people.

Maybe I would aspire to have that be a more natural give-and-take if I didn’t need to swing to extremes. I was at this medieval town in France where when you walk up to the mountain and look down, you can see the walls that encapsulated 300 people. All the gardens are outside. So all the food that fed those people was right there, but everyone behind the walls only knew about their one job -- only one person fixes shoes, only one person makes paper, whatever -- and I thought, “What a beautiful way to live.” To know what your purpose is and to be relied upon to help others? It would be a peaceful place because you take away the question of "What’s my purpose?" Togetherness in all these ways is fascinating to me, and I think that was on my mind while writing.

STEREOGUM: How do you speak about the opposite of that? You begin to touch on soured relationships with “I Wish I Didn't Miss You," especially with the line, "You sent in spiders to fight for you/ I was so disappointed I didn't know what to do.”

FEIST: Sometimes there’s no other way to speak about how dark people can become. It’s like current politics: It can become fictionalized, like the good versus evil of Lord Of The Rings. People can reduce themselves to these oversimplified archetypes.

STEREOGUM: Other times it’s the instrumentation that illustrates separation. Colin Stetson’s horns on “The Wind” does so. What was it like working together?

FEIST: Colin worked on Metals. He was in the studio and we parsed out parts together. But in this case, because we built that trust already, I knew I wanted his thumbprint on that song in however he saw fit. He was alone in his studio in Vermont and just sent back what he made. That’s the type of collaborator that he is. He doesn’t ask for sheet music to follow. There aren’t many guests on the album, so the songs being live performances without anyone else there makes for a special feeling.

STEREOGUM: Speaking of contributions, you wrote a song for Broken Social Scene’s new album and sing on six others. What was that like?

FEIST: I was finished with my record by then because I was grabbing people and putting headphones on them like, “Hey, check this out!” I remember putting them on Amy Milan in the kitchen specifically. I don’t want to sound too Norman Rockwell about it, but reuniting with those guys is precious to me. The fact that we have that place to come together and have a parallel focus? We all have something to contribute to together? It’s great.

The song isn’t specifically by me because we wrote it together, but it felt like the place I could contribute to. It’s a song I brought from Toronto that we jammed on. It was a little similar to Pleasure. As we were working on it for the first half hour, in the back of my mind I thought, “Oh man, this is less Broken and more me. This shouldn’t be a part of this record.” But we were all in the same room and Brendan Canning just started to play a bass line just to shake us up. Then I started to improvise. Andrew Whiteman added a drum beat. Next thing you know, Charles [Spearin] is improvising, too. We all caught that momentum and played for 15 minutes. When we were done, Kevin [Drew] -- who had been sleeping on the couch -- woke up and was fist pumping, yelling “Record that!” That was the birth of the song. It’s called “Hug Of Thunder.” Then I worked on lyrics for the next couple of days and it was finished before I left the studio. It was way less splitting hairs than when I work by myself, because when else do I get to be caught in that type of momentum with all these people I’ve known my whole life?

STEREOGUM: Are you joining them on their tour?

FEIST: When I can. It will probably work out well because I’m not sure when their record will come out. I’m touring the bulk of the summer and they might start in the fall. It could work out well. It makes me feel warm and fuzzy.

STEREOGUM: As you’ve wandered from one band to the next, where do you find yourself now and how does Pleasure fit into that?

FEIST: I find it’s exactly where I want to be and what I want to be playing. That’s as much a result of everyone I’ve played with as much as it is how much time I take between records, how much I wait until I care enough to begin again. Someone asked if it felt like full circle to my punk band from high school, which took me by surprise because, if anything, it’s been a linear path. I have not looked back. It has everything to do with how long I’ve lived and how much I’m looking to the future.

STEREOGUM: What did you discover about your perception of pleasure while working on this album?

FEIST: It had something to do with naming experiences which were mostly to do with difficulty. To name them pleasure, knowing that at this point in my life that these things feed into one another, they become a color wheel. It’s anticipating satisfaction and then immediately planting a new seed of a new thing that you want to anticipate. It’s the getting and the wanting and the getting and the wanting. It can be uncomfortable, a painful side of things, to get caught up in happiness. What I planted in these songs so that 60-year-old me can learn is that the way you look at something is how it will look. What you name something is what it will be. The way you invest in something is how it will grow. I know Buddha has had a few thousand extra years on me and figured these things out in a more graceful way than I can articulate, but I’m clumsily learning them now. You need to learn objectively. It’s one thing when you’re taught something, but it’s another when you school yourself.

Pleasure is out 4/28 via Interscope.