Do kids still pick up guitars and dream of being Jimi Hendrix? His name remains synonymous with rock stardom and revolution, or else a world-conquering rapper like Future wouldn't have named both an album and persona after the guy. And more than many '60s musicians, his music continues to permeate the culture via TV commercials, satellite radio, and such. Like other rock stars who died young, he is a bigger-than-life figure, remembered less as a complex human being than an amorphous symbol for whatever you want him to mean about the '60s counterculture and its ideals. But does anyone aspire to emulate his music anymore?

They certainly did two decades ago, when I was a young teenager in suburban Ohio getting my musical bearings. I distinctly remember walking up to a high school pep rally bonfire outside the football stadium freshman year and witnessing a band of longhaired upperclassmen rocking "Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)," the guitarist gleefully abusing his wah-wah pedal as he noodled away. I thought they were impossibly cool. Forget trying to be Hendrix; I would've been happy to be those dudes.

Back then the concept of the guitar god was still very much alive. Grunge theoretically killed it along with spandex and big hair and commanding a romantic interest to pour sugar on you, but the likes of Kim Thayil and Billy Corgan were keeping the tablature transcribers busy, and millions of budding shredders like me were still spending hours trying to play like Kirk Hammett or Jimmy Page or Eddie Van Halen. I did not find the idea of ripping through an ostentatious guitar solo lame in the slightest. I believed it to be rad as hell, and I spent hours in my basement trying to perfect the art. One of my favorite pastimes back then was walking into Sam Ash and nonchalantly showing off my sick finger-tapping skills for anyone within earshot. So a few months after that pep rally, when I got the chance to form a one-time band with some buddies for a New Year's Eve party, you better believe we performed a lengthy instrumental composition inspired by Joe Satriani designed to let me wail away for five minutes or so. (The ladies were not as impressed as I'd hoped.)

We also covered "Foxey Lady." How could we not? Hendrix was part of the basic curriculum for anyone who sought to become a guitar wizard, and he more or less defined my ninth-grade year. Throughout middle school I'd made my way from top-40 to late alternative-era MTV to a hard rock diet of Metallica, Pantera, and assorted nü-metal knuckle-draggers. My taste was largely driven by what stimulated my own guitar playing. So when I was finally ready to plunge into the '60s and '70s classic rock the music mags were always raving about, my first love was not the Beatles, the Stones, Floyd, or even Zeppelin. It was Hendrix. I bought all the albums on CD. I slaved away trying to replicate his riffs. I exposed my parents to probably more Hendrix than they'd listened to in the rest of their lives combined. I even read a 700-page book on the guy; do you realize what it takes to get a 15-year-old boy to read 700 pages on anything?

For years I've been wrongly thinking Hendrix the musician didn't resonate like that anymore, mostly because our 21st century culture doesn't generally prize virtuosos. I now believe I was off-base about Hendrix's modern relevance for reasons I'll explain momentarily. But before we do that, let's talk about the lost art of the guitar solo.

As early as 2003, when the Darkness released "I Believe In A Thing Called Love," theatrical guitar soloing seemed like a punchline. Nowadays, when the guitar-god archetype is presented with a straight face by Hendrix disciples like Gary Clark Jr., it seems more like historical reenactment than a vital force in modern music. It is, in a word, corny. There are underground scenes in which soloing remains a core discipline: jam scenes, psych scenes, whatever circle Thurston Moore's running in these days. But in the vast majority of popular genres, nobody really solos anymore. And when they do, it's often tightly contained, as on umpteen pop-country hits or the Weezer tracks where the guitar solo just repeats the vocal melody (i.e. most Weezer tracks since the Green Album). The mentality even extends to hip-hop, where extreme technical rapping -- the verbal equivalent of a flashy guitar solo -- has long been relegated to the margins. It's hard to imagine what the modern answer to Hendrix's legendary "The Star Spangled Banner" deconstruction might be.

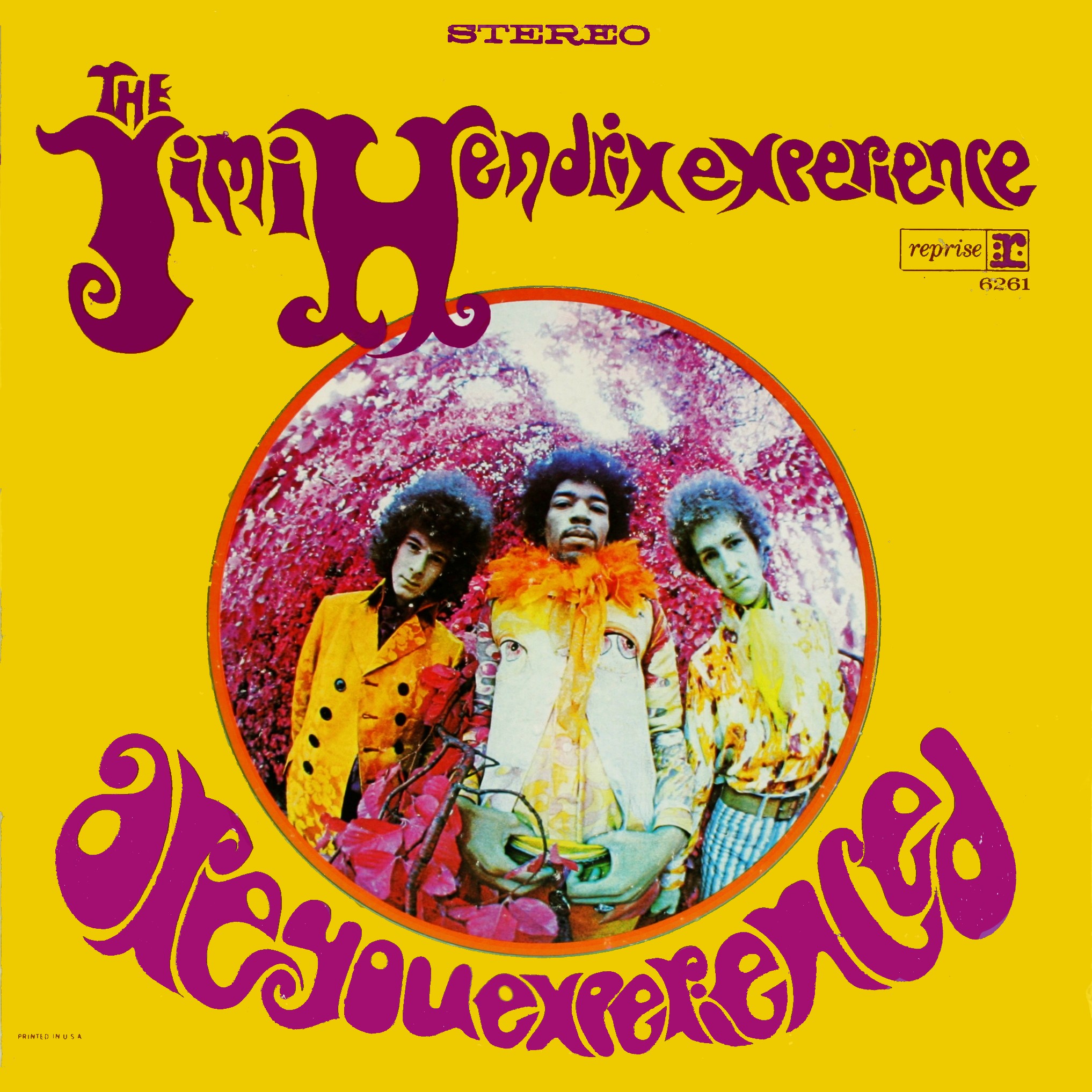

That kind of flex is what drew me to Hendrix as a teenager, but it's not what keeps me coming back as an adult. It's not even what ultimately hooked me when I was a kid. Revisiting the Jimi Hendrix Experience's landmark debut album Are You Experienced, which turns 50 years old today, crazy shredding is not what stands out. There are some amazing riffs and a handful of timeless solos, yet Hendrix's playing throughout is artful and restrained, and no song drones on longer than it needs to. He was an electrifying guitarist, it's true, one who did magnificent and unprecedented things with his instrument. But it would be a disservice to remember him only by his fretwork. He was a brilliant songwriter, too, and a visionary aesthete, one who distilled whole galaxies of sound into potent, undefinable outbursts. He could do it all.

Hendrix's road to Are You Experienced seems like Rock History 101, but that history is also growing more ancient all the time, so let's summarize for the youths: After growing up in Seattle and teaching himself to play guitar as a teenager -- flipping right-handed guitars upside down to accommodate his left-handed playing, thereby helping him to approach the instrument in radical new ways -- Hendrix did a brief stint as an Army paratrooper. Then he moved to Tennessee and spent about four years on the Chitlin' Circuit as a guitarist for the Isley Brothers, Little Richard, and Curtis Squires, also gigging with his own band the King Kasuals alongside future Band Of Gypsys member Billy Cox. In 1966, at the urging of Linda Keith, he moved to London and met the Animals' Chas Chandler, who became his manager and helped him form the Jimi Hendrix Experience with British rhythm section Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell. They scored some minor UK hits, won essentially all of England's rock royalty as fans, and hit the studio to record their debut album.

What they came up with was unlike any album ever released -- and not just because of Hendrix's inventive guitar work, though there's no downplaying his revolutionary approach or the way it shaped everything else about his sound. Like a mutant who'd gained full mastery over his powers, he ably controlled every available weapon in a guitarist's arsenal: feedback, effects pedals, the whammy bar, even his teeth. In concert, that skill set played into wild exhibitionism that extended all the way to his wardrobe, his gigs so explosive that they often ended in smashed instruments (and, famously, once with a guitar set aflame). That showmanship is a huge part of his legend, but Are You Experienced presents him as more than just a marvelous instrumentalist.

On the LP, all that power is reined in and meticulously deployed, often with a subtlety you wouldn't expect from such a showboat. A controlled chaos lingers in the album's background and ramps up at strategic moments, a wave of noise that sweeps through and irreparably alters the landscape of a song. Even if you've never listened to Are You Experienced, you've heard it in the tumultuous closing moments of "Purple Haze," one of the most famous rock songs in history. It manifests elsewhere in the tumbling rhythms of "Love Or Confusion" and the tripped-out space travels of "Third Stone From The Sun" and even the gently drifting ballad "May This Be Love." And it's all over the madcap freakout "I Don't Live Today," the record's closest parallel to Hendrix's untamed stage show. And on the remarkable title track, it's flipped backwards, chopped up, and pieced back together into an otherworldly statement of intent.

Just as often, though, Are You Experienced demonstrates how much this trio could accomplish without a blaring wall of sound. The spare and visceral "Manic Depression" weaves insane riffs and even crazier drums into the foundation for a new kind of blues. "Fire" is similarly combustible, initiating with a riff so startling. "The Wind Cries Mary" is a simple, beautiful display of Hendrix's softer side; to me, his clean, aqueous rhythm work, also heard throughout "Hey Joe," was and is every bit as revelatory as his fireworks displays. Its prominence throughout follow-up Axis: Bold As Love is one reason that album remains my favorite Hendrix release. He trilled and improvised within chord progressions with a fluidity that suggested matter shifting shape before our ears. He imbued those moments with rich melody and impossible depths of soul that helped a wimpy, sheltered kid like me connect with an album about a sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll lifestyle that couldn't have been farther from my own life. There was powerful human connectivity in this music even for those of us who were not particularly experienced.

What I hear now in Hendrix's opening blast is remarkable talent turned loose toward limitless possibility. Even though he'd expand his horizons farther with successive releases, his fearless experimentalism, skewed pop instincts, and ecumenical approach to genre were already fully mobilized on Are You Experienced. Those are his most enduring qualities to me. They're the ones that knock me out whenever I return to his discography. They're the ones I hear reflected in projects like D'Angelo's Black Messiah or Miguel's Wildheart or even Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp A Butterfly: splatter-of-ideas albums that capture the vast passions and complexities of modern life (particularly black American life) and music's parallel boundless potential.

None of those albums exactly parallel Hendrix's sound, which is partially the point. He never saw rock or blues or jazz or R&B as rigid forms, so any dutiful tribute automatically undercuts the ethos of his work. Instead, he saw those disparate styles as colors for a blank canvas, meant to be blended into something profound -- whether personal, as on much of Are You Experienced, or political, as his music began to lean when '60s idealism took a turn for the tumultuous. I began noticing that dimension of his influence a couple years ago. When a critical mass of ambitious, eclectic statement albums like that began bubbling up, it conjured Hendrix's spirit more closely than any endless, reverent 12-bar-blues. I don't know whether kids still dream of being him, but as long as music like that persists, he lives today.