I keep going back to the last time I saw Chris Cornell. In light of yesterday's news, it's the only comfort I can find.

It was three years ago, and Soundgarden were touring with Nine Inch Nails for one hell of a double bill, one strong enough get me to take a train to an outdoor shed in the middle of New Jersey on a Saturday night. Lovingly located to the right side of the stage during Soundgarden's performance were three young children, all wearing headphones. I can't speak authoritatively of the entire grouping, but the one in the middle in the pink dress was definitely Cornell's kid. Between songs of pain and fury and middle eights, Cornell would look in their direction and beam. At one point, he took a break to walk to their side of the stage. Based on the concerned nod and then the relieved nod, I imagine he was doing his fatherly duty, making sure everyone was having a good time. If they needed water or juice, I'm sure he made sure it was taken care of ASAP. Then the band kicked into another song that made it sound like heaven itself was falling down. I think it was "My Wave," but my memory might be letting me down on that one.

I suspect I'll be holding tighter and tighter to that image of Cornell as a sweet, dutiful dad in the weeks to come. Now that his shocking death, only hours after Soundgarden played a show in Detroit, has been officially ruled as a suicide by hanging, it seems inevitable that Cornell will soon join Nick Drake, Ian Curtis, Elliott Smith, and, of course, Saint Kurt Cobain in that club of musicians who will forever be remembered first and foremost for the circumstances of their death, that every time we listen to their music, a black neon banner barring "too soon" and "why?" will be stamped onto every note.

We (you, me, the media, the fans, we) have a distressing tendency to simplify complicated personalities into one-note characters after they die, to remember goofballs like Smith (famous for his love of dirty basketball) and Cobain (who once did this) as tortured artists, too sensitive for this world. What bullshit. Though I'll probably be let down yet again, I'd like to think that society has grown up enough in the past years and learned enough about the importance of taking mental health seriously, and that depression is a disease that can happen to anyone, even beautiful men with the voice and hair of angels, to avoid making Cornell into some kind of martyr. Let's not turn a person into some kind of symbol. Let's instead remember a flawed but brave man who spent most of his life fighting a disease and writing about it as well as any of musician you could care to name.

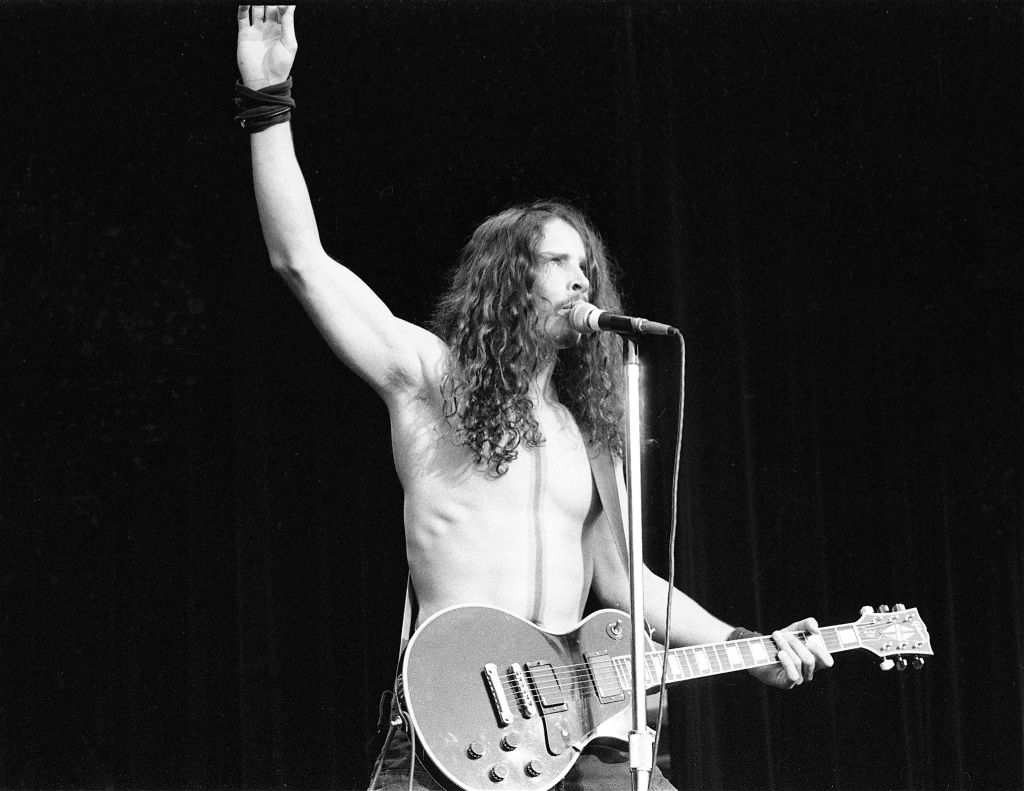

The first thing we think of when we think of Cornell is that goddamn voice, capable of hitting operatic peaks that make most singers look like cowards. That part on "Limo Wreck" where he some pushes the last syllable of the extended "faaaaaaaall" out of the stratosphere into a whole other stratosphere, so loud you could hear it from space? Jesus, I can't even talk about it. Seeing him do it live was astonishing. We'll never see him do that again. But Cornell and Soundgarden had a way of employing their tremendous technical abilities (only Pink Floyd lodged more odder time signatures onto the charts) in a way that never seemed showy. Their unusual chord choices, muted tones, trigonometric tablatures, and Cornell's octave hurtling were necessary to create the disorienting headspaces and internal battles his lyrics demanded. One of their best tricks was piling on concrete slabs of riffs and rhythms so ornately arranged they felt as suffocating as the malaise in Cornell's mind, and only his clarion call of a voice could push it all away. The voice was such an intimidating instrument that it could have done all the work itself. But it didn't. Intricately sludgy hard rock isn't a form that necessarily demands much of its lyricists, but Cornell was capable of uncommon grace rare for any genre. And never more so that when he was staring down the demons in his mind.

It's not helpful to look through Cornell's lyrics for clues to What Happened. In fact, it's more than a bit ghastly, and a disservice to his artistry. Instead, let's just take a moment to appreciate what he accomplished. Soundgarden were incubating in the underground when mainstream hard rock was either concerned with girls and partying (Mötley Crüe and their ilk), drugs and taking drugs (Guns N' Roses), or war, politics, and the sins of man (Metallica and Megadeth). Instead, Cornell went inward. Soundgarden's mainstream breakthrough came with "Outshined" (from 1991's Badmotorfinger), about as succinct a summation of the feeling that everything is terrible even when nothing is actually wrong that you'll ever find, down to the sheer boredom of feeling shitty all the time. ("I kept the movie rolling/ but the story's getting old now.")

Even as the grunge revolution made it de rigueur for rock singers to act like they're deeply tortured by nothing in particular, Cornell continued to make his pain feel genuine, his relief hard earned. He was very open in interviews about his childhood battles with depression (there was a time when he was a teenager when he barely left the house) and later, his struggles with alcoholism and painkillers. And he wrote about it in ways that felt real and non-exploitive. Some of Soundgarden's best-known singles such as "The Day I Tried To Live," "Fell On Black Days," "Blow Up The Outside World," and, holy Lord In Heaven, "Pretty Noose," conveyed through word and mood the feeling that there's no point in trying, in even getting out of bed to face a world full of gray and dull buzz and nothing else. Or as he said, "Just when everyday seemed to greet me with a smile/ Sunspots have faded/ and now I'm doing time."

Plenty of musicians are great at conveying the feeling of being heartbroken, or hopeless, or feeling a vague sense of unease that words can't articulate. Cornell could do all of that, but he also had the rare ability to convey the feeling of being utterly depleted.

Of course, Cornell gave us so much more. He had joyful songs that reveled in the sheer power his voice and his band were able to summon and give to the audience, songs of compassion, songs of defiance; "My Wave" was the progenitor of "I'm doing me" type songs. On Audioslave's "Cochise" and "Original Fire," he sounded offended that you wouldn't get off your ass. On Temple of the Dog's "Say Hello To Heaven" and the early solo cut "Seasons," he poured out from a nearly bottomless well of empathy to mourn his friend Andrew Wood, and marveled how anyone can lose their way. And as Stereogum's own Tom Breihan mentioned yesterday, Cornell could also be quite funny. And say what you will about the Zac Brown and Timbaland collaborations, but it's to his credit that he never stopped trying new things.

So let's remember Chris Cornell not as a tortured artist or a saint for the idea that true art comes from suffering. Let's remember him for what he was. A once-in-a-generation singer. A hardworking, first-rate songwriter. An attentive dad. And a man who fought hard for every one of his days.

//

If you are feeling depressed or suicidal, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255