My favorite footnote about Soundgarden is that producer Michael Beinhorn reportedly had Chris Cornell listen to Frank Sinatra before recording "Black Hole Sun," which was indirectly followed years later by a Paul Anka cover of the generation-defining hit. People make a big deal about the song's Beatlesque sonics, but the Beatles mostly had some economy to their vocal approaches and rarely hung a long-held note in the air out to dry. Cornell’s voice, even on Soundgarden's shorter, more punk-oriented songs, always retained a heavy load. Punk changed his life like any of his peers, but it’s completely impossible to imagine Cornell singing hardcore; you could fit an entire Descendents song inside one of his squeals. Somehow him attempting Sinatra standards seems more plausible.

For all the mix 'n’ match imitations that came after -- Toadies, Candlebox, Days Of The New, what have you -- grunge's practitioners really were so much more colorful and varied than the drab label really accounted for. Mudhoney were something of a post-Stooges garage thing without an ounce of pop ambition. Pearl Jam worshipped the Who and Neil Young from the git. Nirvana aspired towards the purest synthesis of noise and pop and not only found it, they damn near transcended it. L7 made it happen on the majors as pitch-perfect piss-pop robots. Screaming Trees and Afghan Whigs enjoyed having one foot in and one foot out to explore the line between raggedness and sexiness.

That leaves Alice in Chains and Soundgarden, who viewed the opportunities of the Seattle sound as a way to take metal somewhere else. Their vocal signatures were the key. Layne Staley arranged his miserable harmonies into elaborate pretty-ugly textures that floated over the gestating sludge of the riffs. By contrast -- with any of these bands or any other act you’ve got from the era -- Chris Cornell’s whopping range soared over the mix like a bird.

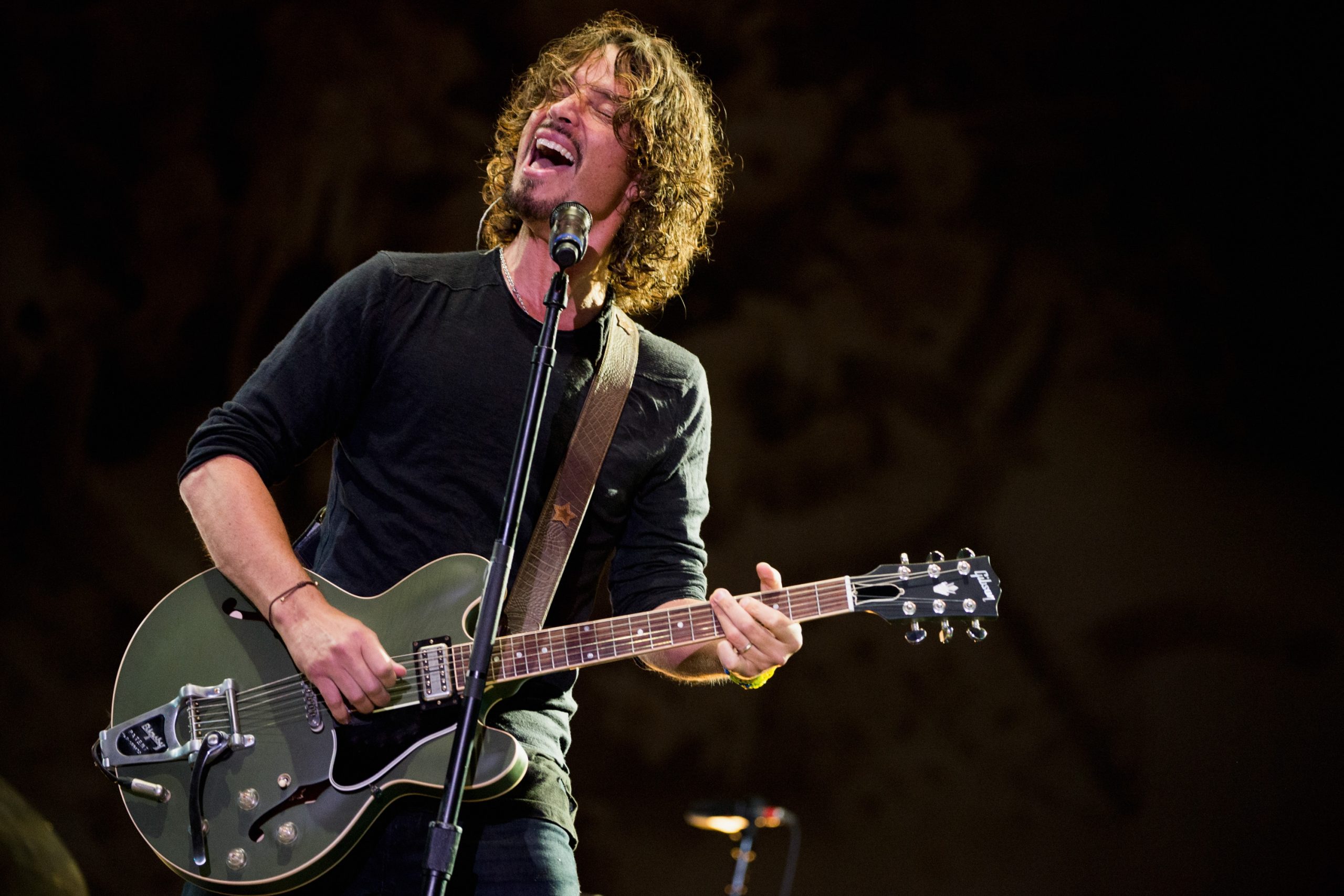

Soundgarden deserve to be remembered for other things, too, like Kim Thayil’s imaginative approach to the guitar, or their complete and total ease writing ostensible pop songs in time signatures that functioned like sturdy, well-made houses that just happened to have been built upside down. But Chris Cornell’s wailing vibrato was a technical marvel in a genre and era that never beckoned for trained talent. That’s the thing: Kurt Cobain was a genius who made a lot of things look easy; Chris Cornell was a virtuoso who did not. "Smells Like Teen Spirit” led stained-shirt teenagers to believe they could have cobbled it together in their garages. “Rusty Cage” and “Jesus Christ Pose” left them wondering how anyone could have created such a thing.

That’s why he’s the grunge alumnus who attempted an album with Timbaland (2009’s Scream) and tried his own take on "Billie Jean," why he got to belt out a Bond theme that’s better than you remember. Cornell’s tastes and throat muscles were in tandem; up until the somewhat repetitive Morello-riff-formula blather of Audioslave it seemed like he could keep unfurling that voice into new configurations forever. The baroque psych-folk of “Can’t Change Me,” locomotive bluegrass-punk of “Ty Cobb,” and alloy-melting grindcore of “Slaves And Bulldozers” all fit the man’s astounding range like a glove. As for the Timbaland, well, it might’ve actually failed for being too limited. Neither visionary really brought their weirdest ideas to the project, which would be more fun to pull apart retroactively if it was more on the Lulu end of the spectrum.

One could easily place Cornell’s vocal prowess neatly on a spectrum where Robert Plant is as equidistant from him as the bluesmen he funneled into something else entirely. Removing the blues from Robert Plant turned out to be a genius artistic development in itself, even though on paper it’s hard to do justice to how seismic and exotic Soundgarden’s melding of art-rock, alternative, and metal was, a combination we now take for granted. Axl Rose was impressed by Cornell early on, even as he grew frustrated that Nirvana’s scene was supplanting his, and you could tell it was Soundgarden’s chops that made a difference.

They had equal parts past and future in their sound. Cornell’s alien wail was never held responsible for crimes against rock music the way Eddie Vedder’s bellow or Layne Staley’s warble were, thanks to the many inferior imitators who followed in their wake. In a purely operatic, conservatory sense, Cornell was just too damn difficult to replicate, and that’s without counting his humanistic, idiosyncratic approach to the same earth-blowing-up stuff that his peers were trying to capture in their own lyrics: “Call my name through the cream,” “I’m looking California / And feeling Minnesota.” He’s underrated for feeding his feral voice some real bonbons of poesy, which at their silliest (“paradigm” is a word that should never be uttered in song) couldn’t really be mistaken for anyone else.

As more and more of our icons are swallowed up by the earth, we’re learning just how many kinds of one-of-a-kinds we really have operating on this plane at once. This man was a huge talent who frequently made his art a two-way street for the artist’s and fans’ depressions to be felt in tandem. He communicated that so powerfully and unshakably from his end. Black hole sun inevitably does come, and hopefully it washed his pain away.