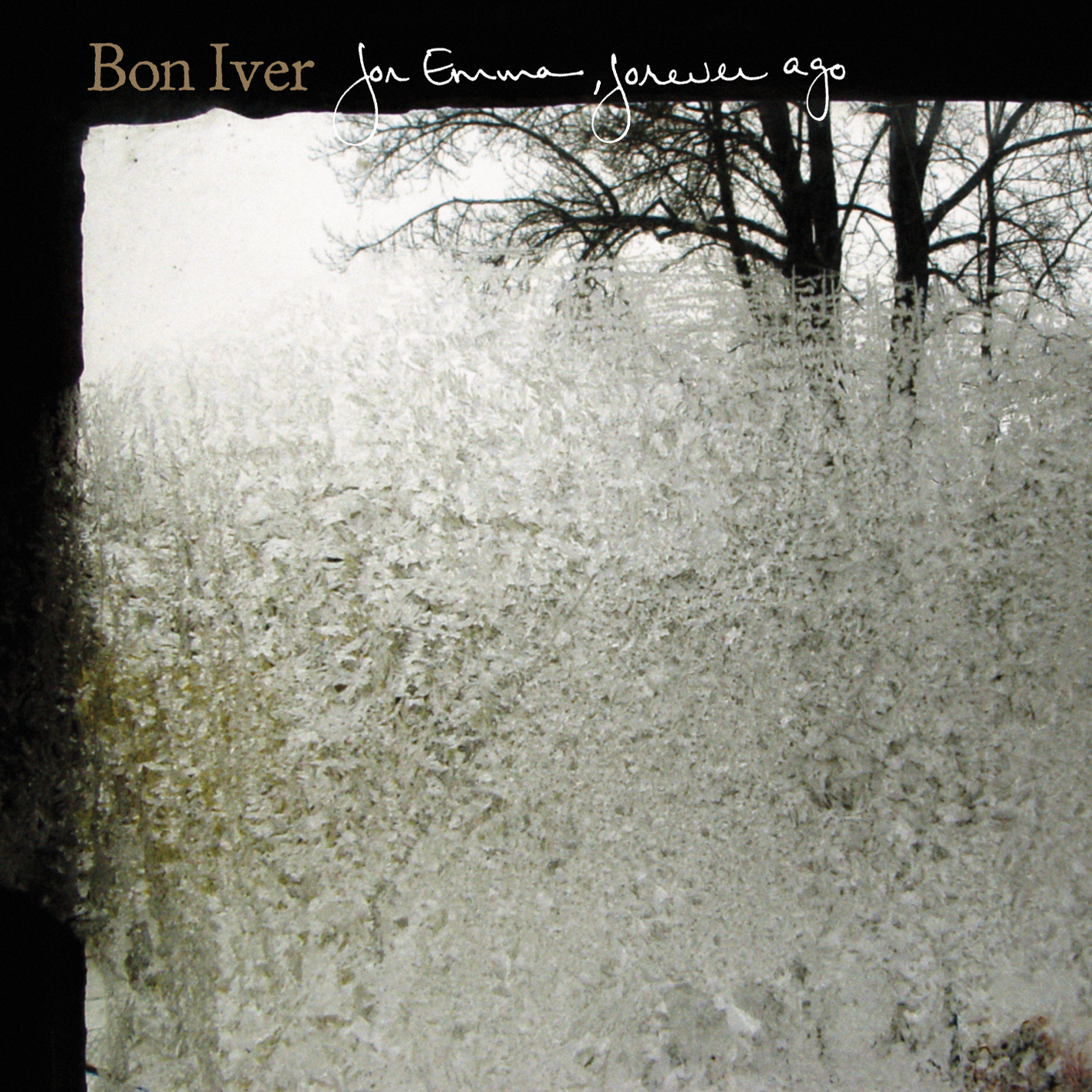

There may be no more mythic origin story in all of indie rock than the tale of Justin Vernon decamping to his father's hunting cabin in the dead of winter and emerging with For Emma, Forever Ago. You probably know it by heart, but for posterity's sake: Aching from the end of a romantic relationship and a band breakup that he believed to mark the death of his music career, Vernon holed up in remote northwestern Wisconsin for three months and spent his days hunting game and strumming an acoustic guitar. As inspiration struck, he traded the straightforward alt-country sounds of his previous project, DeYarmond Edison, for a more elemental yet sophisticated take on folk music -- spare, trembling, otherworldly -- ultimately coming away with a set of songs that crackled and glowed like a wood stove in the midst of a snowstorm. They'd truly catch fire when Vernon returned to civilization and decided to release this new project into the world under the name Bon Iver. It was a slow burn, but Vernon's private catharsis eventually became one of the most influential albums in indie music history; if everyone who bought The Velvet Underground And Nico started a band, everyone who bought For Emma grew a beard.

Vernon would soon be rushing swiftly away from those kinds of stereotypes -- quite successfully, I should add -- but hoo boy, there was some truth to them at the time. Just ask the acoustic-guitar-clutching dude who used to used to hang around my friend group singing "Skinny Love" out of tune and attempting to mack on women. Along with the first Fleet Foxes album the following year, For Emma came to symbolize a movement toward woodsy, introspective, gorgeously harmonious balladry, a platonic ideal of underground music crafted not in bars or basements but, you guessed it, remote rustic cabins. The woodsy indie-folk archetype became such a cliché in the wake of this album's groundswell that it's easy to forget what a spine-tingling work of art For Emma really is. But with its 10th anniversary looming this Saturday, we're all due to remember its brilliance.

To listen to For Emma is to be transported: to that cabin, yes, but also to a wildly different time in music history, a time when bands released their new singles via MySpace and HBO's Flight Of The Conchords was all the rage. Given the ways both Bon Iver and indie rock have changed in the intervening decade, it really does feel like forever ago. Vernon quietly released For Emma in the summer of 2007, though it's likely the album reminds you most of 2008, when Jagjaguwar's re-release vastly accelerated its word-of-mouth rise. (The album and its backstory and even the band name -- a play on "bon hiver," French for "good winter" -- are so unmistakably wintry that it's a testament to this music's irresistible quality that anyone paid it any mind in the summer heat.)

Those years were a weird transitional time for indie music. Gentrification was well underway, but the online music press remained a splatter of diverse niches awkwardly coexisting. Blog-house was popping thanks to Justice and Crystal Castles; the likes of No Age, Vivian Girls, and Times New Viking were spearheading a lo-fi revival; electronic experimentalists abounded, from Burial to Dan Deacon to Fuck Buttons to Panda Bear to Flying Lotus. On the more populist side of things, the National and Arcade Fire and Frightened Rabbit were mastering the art of the brooding, howl-along anthem; DJ/producer types like Girl Talk and Diplo were helping the underground to embrace the mainstream, and a number of ostensibly underground artists were making massive leaps into ubiquity, Feist and MGMT and M.I.A. among them.

One of the foremost subgenres of the time was the aforementioned folk scene, for which Vernon became a sort of unwilling figurehead. Indie rock had experienced its loosely defined freak folk movement a few years earlier, upon the emergence of figures such as Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom, Animal Collective, and Sufjan Stevens. This was not that. Bon Iver probably would have been lumped in with those acts had For Emma emerged a few years earlier, and there was certainly a supernatural quality to hearing Vernon's voice doubled, tripled, quadrupled, interacting with itself in a celestial high-wire act. But whereas the freak-folks mostly disappeared into fantastical realms, Vernon's songwriting was grounded in real life. His pain was almost painfully authentic. His lovelorn lyrics were relatable enough to latch onto and vague enough to fill in with whatever personal drama was gripping your heart. And rather than obtuse harp odysseys or primal drum circles, he presented it in a deeply approachable context of gentle acoustic guitar strums and ambient textures, topped off with the occasional flourish of post-rock orchestration.

For Emma was much more than a singer-songwriter album, but seemingly everyone with a taste for singer-songwriters of any stripe found something to like about it. It became an arthouse blockbuster of sorts, basic enough not to weird out less adventurous listeners but artful enough to capture the ear of those who usually had no time for coffeehouse fare. Thus, it resonated with an incredibly wide swath of people, launching Vernon to heights of fame he'd probably never imagined back in his DeYarmond days. By the time the companion Blood Bank EP emerged in early 2009, Bon Iver was a bona fide sensation. Within another couple years the project's scruffy Midwestern mastermind was guesting on Kanye West albums and being parodied by Justin Timberlake on SNL.

Vernon deserved it. He'd prove that again and again as the years rolled on: first and foremost by delivering two more Bon Iver masterpieces that evolved the project to further heights of creative transcendence and left the woodsy indie stereotype to the trendmongers, but also by developing arguably modern music's most consistently rewarding network of side projects and collaborations. That first Bon Iver album, it turned out, was introducing us to a truly fascinating and transformative figure, a guy who would become one of music's leading lights for years to come and who'd introduce us to a galaxy of other exciting musicians in his orbit. By repeatedly taking risks, upending expectations, and steadfastly remaining true to his instincts, he's become a Bob Dylan figure of sorts, one who got his Blood On The Tracks out of the way up front.

Honestly, though, For Emma would have rendered him a legend all on its own. The album is a rare treasure, a one-of-a-kind work of art. Nothing else before or since sounds quite like it, though not for a lack of musicians attempting to replicate its glories. In a sense Vernon had no choice but to reinvent Bon Iver after this because to go back to this formula expecting another stroke of genius would have been folly. You can revisit the somber calm of "Blindsided" and "Re: Stacks" endlessly, but you probably can't repeat it without diminishing returns. The pensive intensity of "Lump Sum," the ornate resignation of "For Emma," the way "Creature Fear" and "The Wolves (Act I & II)" build up heavenward until embittered finger-pointing becomes triumphant bloodletting -- all of it documents one of those bursts of inspiration that a musician is lucky to capture before it slips away into vapor. For Emma stands as a portal to that moment, and for that the rest of us can count ourselves lucky, too.