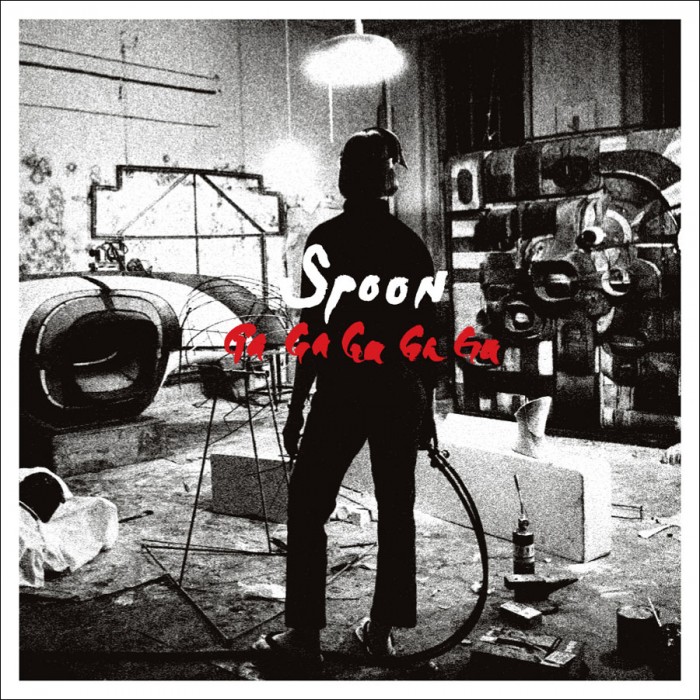

Perhaps it could have been considered presumptuous, but Spoon have never dealt in pretense. They knew Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, the band’s sixth studio album, was a sure thing. And if you followed their career up to that point, you undoubtedly believed it as well, even without having heard a note of new music in advance. By this point, Austin’s premier indie-rock outfit had already earned their reputation as an institution. Over the course of their entire discography -- but most significantly their previous three albums -- the band demonstrated an inability to miss. Again and again, they'd pulled off seamlessly inventive tricks without so much as suggesting a sweat. So when you bought your copy of the LP and it came adorned with the message "This Record is a Hit" printed on both sides, you weren’t demanding proof; you were eagerly anticipating how they’d do it this time around.

Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga changed how we imagined Spoon, both in terms of expanding their sonic possibilities and dislodging them from inevitable narratives waiting to peg their career around an "early classic" like Kill The Moonlight. Our modern impression of the band, captured in quick and easy shorthand like "consistent" and "reliable," wasn’t invented because Ga Ga cemented a winning streak, but rather because it so effortlessly and without fuss broke the limitations anyone would dare impose upon this band. We simply couldn’t contain the magnitude of their capacity in any words less broad and backhandedly-dismissive. Funny enough, Ga Ga didn’t suddenly become heralded as the band at their peak for breaking the mold; it seemingly elevated the impression of all their albums, proposing that although Spoon have a distinct, unmistakable sonic profile, they’ve always been capable of wielding it in a variety of ways that impart nuanced impacts. It’s because of Ga Ga that you can call any Spoon album your favorite without being considered contrarian.

At the time, Ga Ga was received as Spoon's “definitive" album -- a reputation it still holds today, exactly 10 years removed from its release. It was even more boldly experimental and eccentrically euphoric than any of their previous outings, but uniquely casual and accessible in its display of brilliance. It isn’t their masterpiece (Kill The Moonlight), nor is it their most rewarding (Transference, don't @ me), but it's the one that's all hits, even if not many of them were ever released as singles. It’s the culmination of everything the band has since become defined by, the one that you’d point a novice to as the best entry point into their output. It’s the moment Spoon became many people's favorite band -- or at least a widely respected, unloaded, yet commendable response to that dreaded ice-breaker.

While a unanimously acceptable answer, Spoon's appeal is undoubtedly personal. What makes the group so fervently loved by so many cannot be found in universal commercial appeal, but rather in the vast collection of inimitable, individually stunning moments the band has stockpiled across their discography. Both Tom Breihan and Kelly Conaboy touched on this idea earlier in the year when writing about the band, with the former noting specifically how Spoon songs "are made of tiny and perfect little discrete sounds, sounds that always show up at the exact right moment and then disappear right when they should," and the latter offering a few examples: "a specific distortion, a phantom noise, a faraway yelp, that part when the music comes in, that part when the music drops out, that one harmony right there." Ga Ga was a treasure trove of such moments, and each listener forms their own associations with the album through the ones they personally choose to obsess over. Here are a handful of my own:

•Those shuddering percussive ripples that thunder stereophonically a little past the midway point of “The Ghost Of You Lingers,” braying in the background as Britt Daniel speaks over himself from several distinct angles.

•The way the ghostly aurora that trails off at the end of “The Ghost Of You Lingers” suddenly and seamlessly ignites into the blast of tonal shine that begins “You Got Yr. Cherry Bomb.”

•That one line of the chorus in “You Got Yr. Cherry Bomb” that ducks out all the instruments save for a xylophone and handclaps, in addition to one perfectly placed overdubbed yowl by Daniel, before throwing those anachronistic horns back into the mix.

•The guttural “UGH” someone lets loose in a collision with that metallic clang of a guitar on the stupendous chorus-to-verse break in “Rhthm And Soul.”

•When the sample on “Finer Feelings” takes over the song before Jim Eno’s drumming rolls the rest of the band back in alongside Daniel's initial, delightful “Do doodoo do, do doodoo” warmup notes.

•On “Black Like Me,” when Daniel slips into a thin, high register in the middle of his reprise of the line “I’m in need of someone to take caaaaaare of me tonight,” joined by a subtly ramping piano that suddenly settles with him back to baseline.

•The brief, almost-psychedelic orchestral embellishment that carries Daniel from “Oh Junie’s gone” into “day and night” on the same song -- making a strong case that, regardless of if they are, the Beatles should be the most influential rock band of all time.

•All the evocatively succinct turns of phrase Daniel belts out over the course of the album’s 10 songs, my favorites being: “Street tar in summer will do a job on your soul,” “Remember the winter gets cold in ways you always forget,” and “I want to forget how conviction fits/ But can I get out from under it?/ Can I get it out of me?”

Beyond the moments, Spoon’s other signature trait is a visionary knack for using the studio as a songwriting instrument, Ga Ga found Spoon weaponizing the recording process at their most dexterous and thrilling. I’m not an audio engineer, but if I were, Ga Ga would be my reference album for just about every project, whether it be dance rock or deep house or proto-funk or kraut-punk. I’ve often obsessed over the deliciously unsettling, frenetically squirming distortion breakdown on “Don’t Make Me A Target,” or how the echo on the guitar strikes in “Eddie’s Ragga” sounds as cavernous as a seemingly endless hotel hallway yet as intoxicating as an unknown source of perfume late into a drunken simmer. Spoon don’t simply write songs; they craft sounds.

The band’s long-running reputation for economical songwriting has often been misrepresented as a penchant for rigid minimalism. Yet Spoon have always been playfully expressive performers, forging a deep expanse of vibrant textures while still constructing what could be considered "muscular indie rock." Although solely comprising "hits," Ga Ga maintained Spoon’s trademark adventurous arrangements and in some ways actively surpassed their previous distinctions. Take “Don’t Make Me A Target." In lieu of packing the space between each of its choruses with extra lyrical swipes at George W. Bush and more of Daniel's inextinguishable swagger, it instead vamps on the song’s sauntering main riff with stylistic variation, dressing it up and down with jaunty, squiggly guitars and decomposing feedback scuzz. Or consider "My Little Japanese Cigarette Case," which unfolds with a sweeping progression by simply shifting the intonation of its sole lyric. Not a single note is employed unnecessarily, yet even still their self-restraint sounds captivatingly self-indulgent.

Ga Ga is also the most meta-collection in Spoon’s catalog, incorporating recordings of alternative versions and studio inner-workings into a number of the songs' internal fabric. Not only do these serve as little Easter eggs for listeners to discover, they're also streamlined within the compositions themselves. "Don't You Evah," Spoon's iconic cover of a previously far less iconic track, is defined by the initial stuttering chop of Daniel asking Eno to record the talkback microphone being manned by producer Mike McCarthy. It stems from an inside joke about McCarthy’s "ridiculous" comments throughout the recording sessions, but absent from context is purposefully positioned in a way that is almost as memorable and catchy as the song's sticky central bass line itself. With Ga Ga, even the band’s in-house humor is expressed with an auteur’s craftsmanship.

As intentional as many of these choices were, Ga Ga still came across as Spoon's most off-the-cuff effort to date, despite also existing as their most compact and tightly tuned. They achieved this by making the loose elements as essential to each song's gravitational pull as even the most primary rhythms. Where earlier albums like Girls Can Tell and Kill The Moonlight suggested an adherence to musical austerity, Ga Ga let squelching horns, dancing chimes, and luxurious strings into the mix, but still managed to rigidly dictate the terms of their involvement, uncompromisingly incorporating them in a way that seems inimitably Spoon.

On more recent albums, particularly 2014’s They Want My Soul, the band has dialed up the impact of their instruments to new heights of booming immediacy. This localized maximalism -- how Eno’s drums crack like a disciplinary cane or the guitars snap with pulverizing intensity -- complements Daniel's dynamically arresting howl by highlighting the physicality of each individual component. But on Ga Ga, the production never smacked to garner attention, instead achieving it with sheer acrobatic impressiveness. The album isn’t loud, but it’s played with a virtuosic confidence, a knowingness that this music is capable of dominating a room at any volume. Every song on Ga Ga sounds like instant canon, as though these were established classics from a previous era that you’ve only heard about but hadn’t actually heard yourself.

What these songs almost certainly don’t sound like to me is 2007. That year was Sound Of Silver, Boxer, In Rainbows, Neon Bible, Strawberry Jam, and dozens of other more minor works iconic in their bounded temporal associations -- albums where you can hear the decade of distance on the recordings, or at least the crust of nostalgia beginning to cake on your impressions as you revisit them. Ga Ga, on the other hand, feels like 1967 and 1980 and 2013 all at once. It’s not just that the album sounds as good today as it did in 2007 -- although the production and songwriting hasn’t aged in the slightest -- it’s that these songs were so unequivocally presented outside of any trend or era in rock and roll that they could move with us from year to year. Or rather, they keep waiting for us to finally arrive to them at the turn of every timestamp.

And in 2017, where it seems like every agent of "important" indie rock from a decade ago is returning to release an album in a far different musical and cultural landscape to various degrees of receptions but much-discussed fanfare, Spoon are routinely paid less attention than they deserve. We take them for granted in a way we don’t with the likes of Arcade Fire or LCD Soundsystem, deflating Spoon’s output to "small stakes" because knowing the band will stick the landing makes us less interested in marveling when they do. But they’re not only releasing better albums now than almost all of those bands from 2007, they were releasing better albums at the time as well. While perhaps they weren't the definitive act of that era, Spoon were quietly the best, and in the long run there isn't an album among their peers that will be viewed as reverently as Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga by the time we're celebrating its 50th anniversary.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]