"Pursuit of fame is as deadly as any narcotic I have ever used," proclaims the header of Bobby Jameson's blog. He started writing entries in 2007, after a silence so long his former peers in the music business thought he must be dead. That's because, until he left it in the 1980s, he was known as the "Mayor Of Sunset Strip" more for being a relentless firebrand -- whether protesting the Vietnam War or bemoaning his lack of rock stardom and financial success -- than he was for the songs he wrote. Dogged by drugs, alcohol, and attempted suicide, Jameson resurfaced three decades later to relate his tales of woe and set his record straight before passing away in 2015, at age 70. He was never the household name he wanted to be, but now another outspoken figure from Los Angeles is attempting to resurrect his memory. Though it's not a tribute lyrically or sonically, Ariel Pink's latest album, Dedicated To Bobby Jameson, draws some clear parallels between the two musicians just by invoking the name.

Now pushing 40, Ariel Pink (born Ariel Marcus Rosenberg) has lived his entire life on the West Coast pursuing the kind of attention and notoriety so many artists crave. After critics panned his first releases -- mainly home-recorded psych-pop freakouts released via cassette and then reissued on Animal Collective's Paw Tracks label -- Pink signed to 4AD and released his breakout LP, Before Today, in 2010. Whether it had to do with his shift toward a more polished sound or, as he posits, the mainstream suddenly became interested in his particular brand of weirdness, Pink found himself thrust into the indie spotlight. He dragged other obscure acts into it, too, collaborating with R. Stevie Moore, for instance, or ending Mature Themes (the equally praised 2012 follow-up to Before Today) with a cover of "Baby" by Donnie and Joe Emerson, a little-known brother duo from rural Washington who saw their self-recorded '79 LP re-released by Light In The Attic thanks to the exposure. That he would dedicate his latest album to another cult hero is no surprise.

[articleembed id="1790144" title="Ariel Pink Albums From Worst To Best" image="1790158" excerpt="A catalog that gets by on no-filter candor, adolescent humor, and grand-slam hooks"]

Like Jameson, Pink learned that being semi-famous has its pitfalls. His last album for 4AD, pom pom, was all but overshadowed by the controversial statements he made in interviews leading up to its release. After sparking feuds with Madonna and Grimes, and claiming to be maced by a feminist and raped by a dominatrix, Pink was likened to the men's rights trolls of 4chan (a situation exacerbated by the fact that they were also his core demographic). It certainly didn't help matters when he doubled down by saying, "Everybody's a victim, except for small, white, nice guys who just want to make their moms proud and touch some boobies" in an interview with The New Yorker. Pink is defensive about his portrayal as a misogynist, but his comments, time and time again, seemed clearly meant to deflect blame and provoke more ire at once.

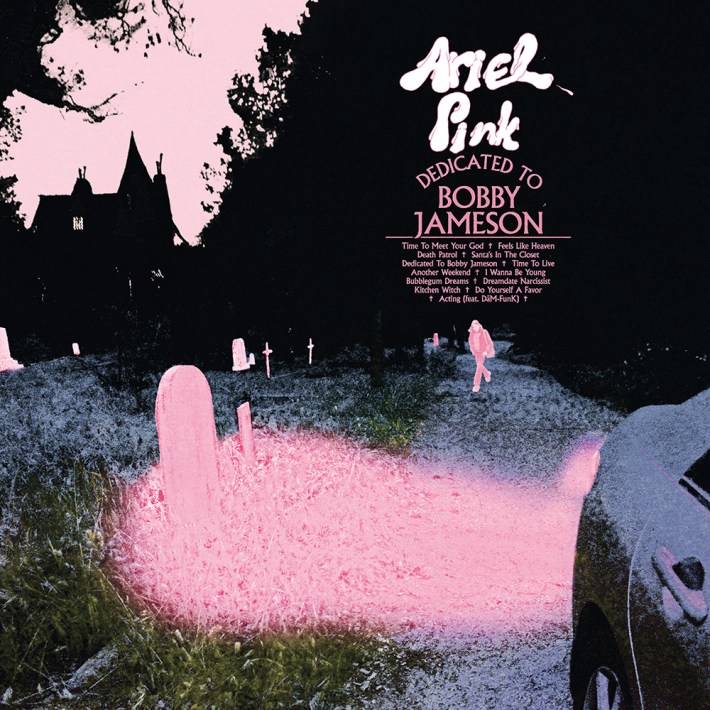

Has the cautionary tale of Bobby Jameson's troubles with the music industry given Ariel Pink any pause? Pink claims that everything he's done from the beginning has been one big experiment in remaining unchanged, for better or for worse. Dedicated To Bobby Jameson, his first LP for Mexican Summer, is absent the trappings of studio recording that legitimized his work for 4AD; his return to a lo-fi approach makes this effort feel more wholly his own while recalling his early Paw Tracks releases. Retro synths, vocal manipulations, and sleazy beats abound, but there are also clever odes to alt-pop acts like the Vaselines ("Bubblegum Dreams") and his perennial favorite, the Cure ("Feels Like Heaven"). But perhaps most telling is contemplative single "Another Weekend," in which a hard-partier takes stock of the damage his debauchery has wrought, or the tongue-in-cheek "Dreamdate Narcissist," in which Pink conjures chillwave by name. Pink seems well aware of his reputation, and remains unapologetic. Though he says he's gotten over the need for attention that initially drove him to begin making music, one gets the sense that his compulsion to maintain a subversive image will die hard, especially when he admits on the Dedicated To Bobby Jameson's final track, "Acting comes naturally, I'm acting out my fantasies." We attempted to get to the real Ariel Pink by meeting up with him for a Q&A in Brooklyn. Read on below.

STEREOGUM: Your new album, Dedicated To Bobby Jameson, harkens back in many ways to your lo-fi bedroom recordings, which is something of a departure from the last three albums you released with 4AD. What influenced that return to those roots, if anything?

ARIEL PINK: Well, I think recording it at home was a big part of it. I pretty much took it back to being more or less me at the helm of the recording. Of course, I did have plenty of guests on the record; there's plenty of other people's contributions. It's not exactly like the way I used to do it when I was at home alone by myself with my 8-track. It's been several years since I got out of my house and started recording with a budget, and in studios, and with band members and stuff like that, and it took me that amount of time to learn that it wasn't the ideal way of working. I brought it back home, where you don't have to worry about hours, or punch a clock or anything like that. So that made it a lot easier and left me wondering why I didn't do this a lot sooner.

STEREOGUM: Those studio-recorded albums were well-received critically; do you feel like they were lacking the Ariel Pink thumbprint? What about home recording feels more authentic to you?

ARIEL PINK: There's just less negotiation, less things in the mix that basically dilute whatever it is that I do. You have to make compromises and decisions, and the less pushback that I get, the less obstacles that are in my way, the more my sensibility shines through. And mind you, that's arguably what people require. My job is to be me, so I'm not doing my job if I'm turning into something else completely.

STEREOGUM: Did the disdain for that process play into your decision to work with Mexican Summer instead of 4AD?

ARIEL PINK: Well, the deal with 4AD was for three records, and we satisfied that deal. My experience with 4AD played into my decision to jump ship -- not saying anything bad about 4AD. You sort of want to get married for a little while but there's this planned obsolescence. I wasn't marrying them for life, you know? Basically, Mexican Summer was interested even before we signed to 4AD. The fact that they were interested afterwards and throughout does bode well for my decision to go with them. And their label has come a long way since they first started, so it's good to see that they're thriving or at least above water. The difference between them is stark. One is like, you're part of a small piece in a bigger machine; you don't have as much personalized care and attention. I think Mexican Summer is really investing a lot in what I'm doing, as opposed to 4AD, where I was more of a pet rock on the manager's table, a gift, not something they were really gonna invest much in. Everybody wants things to succeed, but to a point, because then it gets really complicated. They want their indie cred, but they also, don't want to have to be accountable to people for the rest of their lives.

STEREOGUM: What about your collaborators? Between this album and pom pom, you've worked with a lot of other musicians -- Weyes Blood, Dâm-Funk, Miley Cyrus, Theophilus London, Avalanches, Puro Instinct, Lushlife, Mild High Club, and lots of others. Did working with other artists influence the way you approached this record?

ARIEL PINK: Yeah, I mean that's just a natural consequence of being higher profile and in demand. That's also a consequence of my having a publishing deal in which my job is to do co-writes with people. Not those people specifically, but I'm constantly scheduling co-write meetings with producers and other songwriters and we're writing songs for other people. That's part of the nature of what I do.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Ai7iTqXjVI8

STEREOGUM: Do you like that process or do you find it distracting from making your own music?

ARIEL PINK: It's not distracting. It's something else. It's not my music, it's our music. It's kind of like, the difference between doing a record at home or doing it in the studio with a band. It becomes less my thing, even though my name is still on the marquee in a lot of instances. There are things I don't necessarily want to own as my thing, because they're a group effort. The best way to deal with my career is just to have as little of other people's say so, and they would probably agree. Anybody that gets involved wants direction from me; I would love nothing more than to just get a bunch of geniuses to come up with all this stuff, but if they don't make those creative decisions. Lyrics are a perfect example of that. I have the hardest time writing lyrics for stuff, and I would love nothing more than to just have somebody supply the lyrics. I make the music; I just think in music terms. So that's what I do first and then I sort of have to trick myself into doing the lyrics at the last minute in order to settle on them. I do them right before I record them. So by the time I've recorded them, it's like, oh shit, I can't correct it. I don't go back a million times. If I wrote the lyrics beforehand, I'd have all the time in the world to edit them and I'd never settle on anything. That's a way to trick the real me, without any kind of cosmetics, into basically just doing the thing because nobody else is doing it. It's the last thing I have to do -- just settling on words without having to think about them and be so cerebral about everything.

STEREOGUM: Do you think that makes your lyrics more authentic to how you're feeling?

ARIEL PINK: They're closer to being in the spirit of the thing. It's not rocket science. I don't think what I'm doing is what Bob Dylan does, for instance. I think there has to be a sort of recklessness about certain things. The face of it has to be less manufactured.

STEREOGUM: There's a certain value in going with the first idea -- a lot of times it's the freshest, most immediate.

ARIEL PINK: Exactly, because that's what we're dealing with. We're dealing with rock music, for lack of a better term; pop music. So the face on top of the music, that's the attitude. Otherwise the music doesn't have an attitude. It's why it's so important to have lyrics and have singers. Having words somehow takes the listener above and outside of the music. The music is just background. It's supposed to be the soundtrack to the person's thought process, and [the words and music] are somehow supposed to align, as if they have anything to do with each other, but they don't. I mean, the music comes to me in a much more organic way than lyrics do, so in order to parallel that process you have to sort of trick your mind into saying things that you might not say in any other instance and be okay with it, not worry too much about the meaning, and not worry about the message so much as you create a message by degrees and in little places. The themes of the record that you're alluding to, those aren't themes that are necessarily in the lyrics at all; those are like impressions that are left and solidified and put in the spotlight, those are cosmetic things. Like the album art. Those are all impressions that contribute to where your focus is. It's about fantasy, it's about creating different moods and different focal points that you sort of highlight and say oh okay, well this record's about this because it unfolds this way and the song titles are like this, and you sort of come up with the content after the fact and reflect on it and say, this is about this. It's not really about that, obviously. It's much more open to interpretation, but at the core it's not about anything.

STEREOGUM: Well in terms of the theme, you went with something pretty concrete -- the title of the album, and one of its tracks, is Dedicated To Bobby Jameson, this tragic little-known figure in rock 'n' roll who later in life blogged about music industry woes. How did you become aware of his story and what part specifically resonated with you? Why did you choose him as a sort of totem for this album?

ARIEL PINK: I discovered him probably about a year after he died. My friend Giddle Partridge was friends with him, and she pointed me to some of his YouTube rantings. That sort of led me to his blog, which is like his unpublished autobiography, and I read that. I was totally taken by it. I found myself completely engrossed in his writing voice and his story, how well his memory served him, but also the urgency he was writing with. He's not a writer that decided he was going to be a writer. It's not like he ever intended on writing a book about his life. He's grabbing you by the collar and saying, "This is what happened, OK?" It's basically like when you hear a record by people that have no business playing instruments or writing a record, and it feels like a treat. So, it was that, in combination with the way that it resonated with me. There's so many aspects to it; of course I identify with him in many ways. But also just like, the fact that his story, or his Wikipedia entry, the way that people now see it, is all from his mouth. He could've gone to his grave without writing the blog and no one would know anything. That's not a fate that usually befalls a person -- they don't get to write out their destiny. It's usually a consensus; what they say is the least important part. Nina Simone -- we know she's as crazy as she is, not from her autobiography, but because we see it from everybody else's vantage point in the consensus. [Bobby Jameson's story] is a triumph, and the irony behind it is that he lived just long enough to set in stone his version of the events. That's like, wow, what an amazing way to go out.

I think it says a lot that people thought he was dead for 30 years just by virtue of the fact that he wasn't feeding the madness that came to typify his identity in the music biz. He was barely known from the get go, but if he was known, he was known as essentially that guy, like one of those annoying types that you avoid on the street. There was no Summer Of Love for him; he went straight to Helter Skelter, like in '64 right off the bat. His manager just died a month ago, Tony Alamo. Before he was a religious cult leader-slash-pedophile rapist serving 200 years in jail for these notorious crimes, he was a pot-smoking manager in early '60s LA, with Bobby Jameson as one of his acts. The people on the periphery of his story, they all were way more famous than him. They weren't famous yet, when they worked with him, but they would eventually become famous. They were feeling out their first moves in the whole thing, and he barely merited any mention from any of them.

STEREOGUM: He was more of a fly on the wall in that whole scene.

ARIEL PINK: He was a gnat. He was a nuisance. He thought he was a rock star; he just needed to have the right deal come by, and he would just get what everybody else around him was getting. Everybody was sort of like, fielding the thing properly but somehow he was just stuck lamenting about how he never got paid for his first recordings and that just annoys everybody. Then he became that guy that's on the sidewalk that's basically just a belligerent asshole that you don't even want to talk to. And then he's the guy that's trying to commit suicide every other week. It's the saddest thing, but that's because he was so wrapped up in his identity as a rock star that was on the verge of making it for 20 years. You're supposed to have grown out of this by the time you're 20. Everybody else and their mother sort of has a record deal, shows up, goes away, and life goes on. It's a youth movement. You're supposed to grow up. Well, he didn't grow up, and he never got his five seconds just to like, quell his anxiety about it. And it was still there 30 years after the fact, even after people were like, "he must be dead," because he's not jumping off the Capitol Records building.

But the funny thing about that is as soon as he came back online, in 2007, it was as if his anger and angst that he harbored in the late '70s about it, right before he ditched LA and went up to San Luis Obispo and became a Hells Angel and a bricklayer and took care of his mom in a trailer park, it was like no time had passed. He fell right back into the same archetype and essentially was coming online to stop traffic.

STEREOGUM: That's the beauty of blogging; it gives a voice to those that otherwise aren't afforded an audience.

ARIEL PINK: They still didn't want to hear him! Nobody wants to hear anybody complain because nobody wants to feel responsible. They don't wanna be the reason why he's on the streets.

STEREOGUM: Do you feel like his experience with the music industry is a bit of a cautionary tale? Obviously things have changed since the '60s --

ARIEL PINK: I think it's pretty much the same, and that whole idea of fame is a real elusive thing. It's just a feeling that people have. To many people, I might be famous, but I know differently. I know that I'm not famous. I have friends that are talented, that look at me as if I've made it and beat themselves up over why their ship hasn't arrived. It's a matter of how you feel. That angst that I had -- I didn't even realize I had it, mind you -- I just wanted a little bit of love and attention. I didn't even realize it for 26 years, you know? Then when it came, it was like, aw shit, that's it? I don't have the same urge or drive to create like I used to. That was all just a desperate plea for attention. Maybe that's what informed it and made it so vital at the time, but that's gone now. I had to rearrange my mind on how to write songs. I definitely don't do it the same way or for the same reasons that I used to.

STEREOGUM: Is that the idea behind "Time To Live"? Reminding yourself to get out of bed, make music, function with some normalcy?

ARIEL PINK: What is it they say in Shawshank Redemption? You gotta either get busy living or get busy dying. It's just bullshit. Take it with a grain of salt. I feel like Bobby Jameson's life, I identify with it. That angst part was me before I felt that acknowledgement, and once you feel the acknowledgement, you can move on. Art is this weird therapeutic thing; you're supposed to actually do it so you don't have to do it anymore. You should get to a place where you've expelled it. Anybody that says that they're an artist and keeps repeating the mantra like if they say it enough times it'll be the case, there's an insecurity there. They use that as a safety net but it's also a crutch. They'd rather be "artists" than be happy and actually purge. God forbid they should stop making "art." So they use their misery and their hardship as a sort of grist for the creative mill, and that's a completely retarded thing. And everybody encourages it. It's juvenile, but that's what we expect from our artists. We infantilize them; we don't want to see them act responsibly. And when they act responsibly like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koontz, we bring them down to size. We really don't like success. We don't want to see success. We resent people that succeed. Look at Donald Trump. [Success] didn't really buy him that much respect. We just hate that guy. He can't do anything right. He's made a good living for himself but as far as we're concerned he's the most evil person on the planet. I don't think there's anybody that's been more hated in their life, has more people hating him, than him.

STEREOGUM: Lots of people voted for Trump based on his business "success" without thinking about whether he'd be a successful politician. Don't you think the hatred might stem more from his propaganda and harmful policies? If anything, it's the fact that he's deemed himself a success without being able to back it up.

ARIEL PINK: But the guy can't get any love from the media in this country. I think he's a success story. Before he was president, he was a success story. He has a family, he's got an empire. Success is subjective, but if somebody thinks of themselves as a success, I guess that's the first step toward being successful. Obviously if somebody feels like a failure, everybody casting them as a success story is fooling themselves because that person doesn't even feel successful. That's kind of almost like putting them down. But [Trump] obviously does feel that and we're like, obviously you're way up your own ass. I really think that the world is on its head, almost across the board. People's priorities are really confused and fucked up. There's a lot of distractions and confusing things. I'm not saying that he's not confused. But I would be too, if I was the most hated person on the planet almost universally. If you couldn't get love anywhere, wouldn't that fuck you up? Nobody looks at themselves as being a contributing part of that. Nobody takes responsibility for producing a monster like him.

STEREOGUM: Do you think he'll be remembered as a successful president?

ARIEL PINK: I think it puts a blinder on when he hasn't even started his presidency and people are already saying that he's not gonna be remembered as a good president. Think about the damage that might do. Who's damning the chances? People are already too caught up in legacy things. Maybe that's why we've had a run of bad luck in certain government policies. Donald Trump symbolizes to me how everyone has it wrong and people don't appreciate how much they have it wrong. They don't take the opportunity to look at themselves and say, what's wrong? They're just like, that's not America and that's not me! No, that's you. It's you, you live here, you are America, you are that, you are Donald Trump, whether you want to believe it or not. You haven't faced it.

STEREOGUM: Do you support the president's policies?

ARIEL PINK: I'm a devil's advocate. But I'm an American in a very real sense. I would've supported Hillary, anybody that got into the position, because I believe that America should stay alive and whatever that takes, I'm all for that. There's nobody that I wouldn't [support]; you could vote a four-year-old in and I would be all for it, but that's because I'm a greedy capitalist.

STEREOGUM: So is the greedy capitalist mentality what propels your music now that you've purged your need for attention, as you put it?

ARIEL PINK: Not even. What's driving my career as an artist, is that I'm a career artist. People might see me as a hack or whatever. That's fair enough. But I do what I do. Maybe I would do it anyway, do it differently and perhaps better, and maybe people would love it if I didn't get any attention. They'd like to believe that I've lost something, and I have. I've lost an innocence. Maybe innocence isn't always the goal. It's where you start. But cynicism is the killer of innocence so part of me is like, you know, Ariel, you have to get back in touch with what it was that made you enter into music and what was so life-changing about it. If you look closely that innocence is still there, maybe. You will not be in touch with that if you're not doing that part of your job.

STEREOGUM: Do you like being in the spotlight and doing all these interviews?

ARIEL PINK: No, I hate it. I hate it. I despise it, but I do it, like a job. The cynicism is in the irony that I have to sit here for a week with wall-to-wall interviews focused on me, coming back to the same questions that I have to repeat and I don't believe after I've repeated them so many times. I can't really settle on anything about myself. It's like a primal therapy session, an interrogation that never ends. People want to focus on me and I'm basically like, no no no, let's talk about Bobby Jameson. That's the whole point -- it's a way to distract, obviously. I realize that now. I only realized it after the fact though. The song itself, there's no lyric that says "Dedicated To Bobby Jameson." There's no reason why I should've named it that way; I came up with the album title before anything else, and I had to have a song that was named that. Why do I do these things? There's no theme on the record. It's because I'm basically trying to take the spotlight off of me.

STEREOGUM: Was that a direct response to the press you got leading up to pom pom? It seemed like every interview you did was more controversial than the last.

ARIEL PINK: Yeah. I got the Donald Trump treatment before Donald Trump. I could've warned him. The very first interview I did, an Australian interview at the top of the campaign, set the mood. That guy just had daggers in his sights, and I hadn't even settled into the groove of doing the campaign for the record, and it was very alarming, very obnoxious and very destabilizing, especially at my age. I'm not Hitler. I'm not a Nazi. I'm a harmless lover of things. And I love Madonna too! Way to ruin my chances with that lady. She's so great! She's had greater success and a greater string of memorable hits that I like personally than almost any of my favorite artists, and yet here I am, people saying that I'm throwing her under the bus. I was paraphrasing what the label said to me. People think that I was saying those things. Interscope came to me saying her last record didn't do too well, she had her Avicii, she had all these things she wanted but there weren't any songs there, so that's why they were looking for writers. I was paraphrasing why they would hire somebody like me for somebody like her. So those aren't things that I feel about her -- the stripper pole shit or whatever -- those aren't my feelings. I want to work with Madonna! They were just looking at songwriters, so the next record could do better than her last one. That's all it was. And people take it as my opinions that are valid; that's not even my opinion!

STEREOGUM: Well it didn't end with Madonna; there were lots of choice moments that people latched onto. You were sort of branded as a troll.

ARIEL PINK: Yeah, because I was responding to people completely misrepresenting me, and that was like a witch hunt. I felt persecuted. I don't know how you would feel, if people said that you were a mansplaining men's rights activist. What if they said that about you? And all the feminists in the world basically came out and started getting on your case. So they would go after you, and you would basically try to downplay it as much as possible but they're just not letting you because they're saying you're just fucking wrong, dude. It's a perversion of whatever it is that they projected onto me.

STEREOGUM: So you're saying that your statements were taken out of context and twisted?

ARIEL PINK: Yeah. Like when I say Grimes is stupid for saying that Ariel's characterization of Madonna is a perfect example of the misogyny that's in the business today. Making me, again, an adversary, when I have nothing but great respect for both Grimes and Madonna. The headline was "Grimes Is Stupid" because I "hate women." It backs up my hatred of women and of Madonna. So you see how it's just willful blindness on the part of everyone.

STEREOGUM: Do you think the internet makes it harder to make an offhanded comment? Do you find yourself having to watch what you say because everything is under more scrutiny?

ARIEL PINK: You need to be in the room with somebody to get a vibe for what they feel and what they think, and even then you can only take it for what it's worth. You might not know somebody through and through just by meeting them once or twice. There's all these layers that are mediating the impression that you're making on the world, and reading something that I said is one way of totally polluting what my message is, one way of bringing what the writer says, what he pays attention to, quoting me out of context and that kind of stuff, without any of my mannerisms. People are being manipulated to think one way about me, one way about anybody. For me, it just hammers the point that you really have to take what the world thinks and what you read with a grain of salt in every respect and you can't really believe anybody. That fuels my angst a little bit. But it's good, there's a little fire left in me. I thought I had extinguished all of it, but here I am acting like a petulant 13-year-old again. Maybe that's a good thing.

STEREOGUM: So you feel like you learned from that process? Do you have deep takeaways from your time as the most hated man in indie rock?

ARIEL PINK: I'll be lucky if I ever get that kind of coverage ever again.

STEREOGUM: All you have to do is say something controversial.

ARIEL PINK: All you gotta do is listen for something that might be perceived as that and seize on it. I've already said it, I'm sure. I've already said plenty of scandalous things.

STEREOGUM: So you don't start out to say the scandalous thing; it just comes out and lives a life of its own in print?

ARIEL PINK: No! I mean, I love that I am a harmless pipsqueak in the world and I've got goodwill, and I'm the one that is seen as a threat. That to me is like, poetic justice on its head. It just shows how right I was back when I was a little a kid about how wrong the world is. My angst was right back then and continues to be today. There are still kernels of it. I really just think about what kind of example we're leaving for future generations.

STEREOGUM: In what way?

ARIEL PINK: Oh, like in the way that we want everybody to be really honest about everything. Honesty is such a huge thing, trust with other people. It's overrated. We don't really want those things. Certain things should not be encouraged. I don't necessarily need to speak my mind all the time and be one 100% genuine and truthful.

STEREOGUM: As a protective maneuver?

ARIEL PINK: We need to protect things; honesty is not the best policy. I like to express myself and not care about the consequences and think that I should be able to, without having to be crucified for what I say, but that's very naive of me. And I can understand a little bit more about why parents present a different picture [of themselves] to you [as a child]. We end up resenting them a lot of times as hypocrites, but I think that's because we really misjudge the core reasons why they might say one thing and do another. Everybody's got blood on their hands. I represent that in a lot of ways. I'm not the future of music; I'm dad rock now. I'm old hat. I don't think I'm young anymore.

STEREOGUM: Well the album has pop moments and shoegaze moments --

ARIEL PINK: Different types of dad rock.

STEREOGUM: But it is still a little out there. It's still probably too weird for Steely Dan fans.

ARIEL PINK: It's easy to be weird. You just have to not be whatever's happening in any given 15 minutes. It's easy for me to be weird; what's weird to me is there was 15 minutes when I wasn't weird, and I'm less weird now than I was before that time came. I'm a lot less weird now than I seemed for most of my life, and to me it's because the world came to me on my terms. It became fashionable, got taken in and absorbed and blown up and now it doesn't sound as weird anymore as when it first came out. I was much more of a scourge, of a turd in the punch bowl. It's hard for people to understand that if they weren't there or if they're just coming into seeing it from a different vantage point, that's gonna be paved over.

STEREOGUM: What about songs like "Death Patrol" and "Santa's In The Closet," which really subvert pop music and are reminiscent of back catalogue oddities like "Creepshow"?

ARIEL PINK: It all harkens back. I don't really change that much, ever. It's really all still melodic. I don't progress. Whereas your Mac DeMarcos and everybody else is gonna basically develop with the times, incorporate whatever. People change depending on the climate. I don't really change, never did change. Maybe the fidelity gets better, but the template is just basically the same.

STEREOGUM: So those 15 minutes where you weren't considered weird was because the zeitgeist actually got weirder around you?

ARIEL PINK: I just happened to be passing through when the microscope happened to notice me. But it's as weird as it ever was, or not weird; I don't do anything really atonal. It's like, making melodic-retro-something-or-other. I don't know how I feel about it. To me it's a weird art experiment I did with myself. I wanted to not change. I wanted to actually see what would happen if I decided to plant myself in Cure-land for like, all my life. I wanted to be perceived this way. I wanted to micromanage my image back in the day, and it was an experiment to not progress, to be completely against change, to see what happens when you don't change in the face of change that has to happen; you can't stop change from happening, so why try to change with the times? What happens when someone doesn't change and stays the same and does the same thing over and over again forever, forever? There should be more examples of people just doing what they always did and not really feeling the pressure of modernity imposing upon them.

STEREOGUM: So more than the music itself, remaining unchanged is your grand statement?

ARIEL PINK: My grand statement is that I knew what I was doing back then and I know what I'm doing now and I'm just gonna keep on doing it. I guess I'm not very ambitious. All I needed to do was pay my rent for me to feel successful. It's pretty low-hanging fruit.

Dedicated To Bobby Jameson is out 9/15 on Mexican Summer. Pre-order it here. He's touring behind the album, too. Here are the dates:

10/13 Joshua Tree, CA @ Desert Daze

10/14 San Francisco, CA @ The Chapel

10/15 San Francisco, CA @ The Chapel

10/16 San Francisco, CA @ The Chapel

10/19 Portland, OR @ Revolution

10/20 Vancouver, BC @ The Venue

10/21 Seattle, WA @ Neumos

10/23 Salt Lake City, UT @ Metro Music Hall

10/24 Denver, CO @ Bluebird Theater

10/26 Minneapolis, MN @ Fine Line Music Cafe

10/28 Chicago, IL @ Thalia Hall

10/29 Detroit, MI @ El Club

10/30 Toronto, ONT @ Phoenix

10/31 Montreal, QC @ Le National

11/02 Boston, MA @ Brighton Music Hall

11/03 Philadelphia, PA @ Union Transfer

11/04 New York, NY @ Le Poisson Rouge

11/05 Washington, DC @ 9:30 Club

11/07 Atlanta, GA @ The Earl

11/08 New Orleans, LA @ Tipitina’s

11/10 San Antonio, TX @ Paper Tiger

11/11 Dallas, TX @ Tree’s

11/12 Austin, TX @ Sound on Sound Festival

11/14 Phoenix, AZ @ Crescent Ballroom

11/15 Tucson, AZ @ 191 Toole

11/16 San Diego, CA @ Belly Up

11/17 Los Angeles, CA @ TBD, more info soon