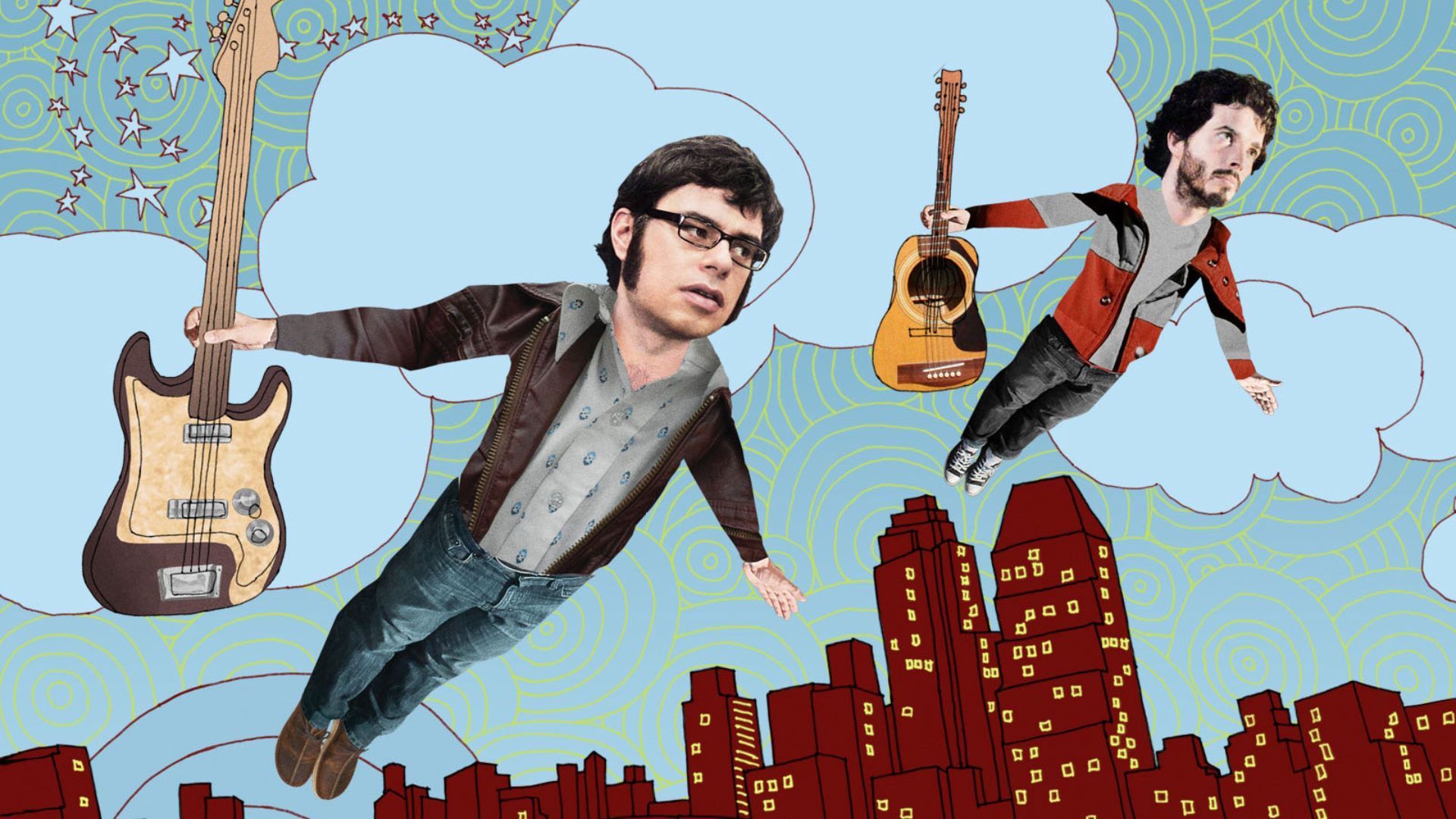

Rock 'n' roll may be the result of combining sex, drugs, and a few good blues guitar runs, but at its best it's all about friendship. Guess it would be kind of odd if the motto was: sex, drugs, friendship, and rock ‘n’ roll. Doesn’t roll off the tongue as nicely. Regardless, the type of companionship that is forged through laughter, not intercourse, spans from rock at its rowdiest (Mick Jagger and Keith Richards) to the genre's softer side (Simon & Garfunkel). Friendship has also been the core of some great comedy -- think Amy Poehler and Tina Fey or Rick & Morty. Each art form embraces excess, and they both benefit from a good duo. Even the interaction between rock and comedy is arguably itself a friendship of sorts. Friendship enhances the meaning of everything. It's the reason why burned CDs mean that much more when they come from someone else, and why getting drunk alone is much more depressing than with buddies. And it's one of the reasons why, 10 years later, Flight Of The Conchords are still a hilarious musical treasure.

Although it had a short two-year lifespan, the Flight Of The Conchords television show is instrumental in the catalog of rock comedy. The show was created by James Bobin, Bret McKenzie, and Jemaine Clement. It stars an animal-shirt-wearing McKenzie and a confused-most-of-the-time Clement as fictionalized versions of themselves: New Zealand shepherds who leave their flock and move to New York City to succeed as a band. As you might have guessed, it’s difficult. They have an incompetent manager named Murray (Rhys Darby) and one creepy stalker-fan named Mel (Kristen Schaal). The duo's relationship is odd and clingy. They both get jealous when the other gets a girlfriend. The band breaks up in almost every episode. They’re sensitive men trying to navigate the concrete jungle, begrudged Australian counterparts, and the trials of love.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Their great and peculiar friendship influenced one of my own. I’ve known my best friend since first grade, and 16 years into the relationship we still argue about who's Bret and who's Jemaine. Although the show ended in 2009, which was the same year the real-life Conchords released their last LP, it's something my friend and I always come back to. We were in seventh grade when we discovered the Conchords. I probably had braces. I probably wore an unexplainable amount of eyeliner. I probably thought I was being rebellious when I told this girl to go to hell over cheating at four square (this was way before the app). It was pre-adolescence, the second most awkward stage of life behind full-blown adolescence. It made perfect sense that the awkward, irrational humor of Clement and McKenzie was our gleaming comic beacon.

As far as rock comedy goes, the Conchords are not as sharply topical as Weird Al or as masculinely nerdy as Tenacious D. They wrote about robots, David Bowie, and the trope about women just being hair and legs. They wrote a whole song in French that is basically an introductory high school class for any Francophile. They wrote about cheering each other up. They wrote about The Lord Of The Rings, tea parties with their grandmas, and brushing one's teeth as foreplay. They made fun of the hyperbolic pick-up lines douchey guys use to pick up babes. They even wrote a song about a fictional racist dragon that cried jelly beans.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"If You’re Into It" still makes my heart glow and my face smile every time I hear it, like the chemical reaction after witnessing a great rom-com. Jemaine joining in on Bret’s ode to a lovely woman is impeccable musical wing-manning. Jemaine brings a cacophony of instruments to help his pal out. Things go from charmingly weird to just weird as Bret suggests a threesome with her roommate in the kitchen. It's one example of how the Conchords took real adult issues -- in this case, sex and consent -- and broke them down into particles of humor that allowed you to connect the dots regarding the heavier matters while leaving the music and jokes in the spotlight. It’s accessible, relatable, and ridiculous.

2007 was a high point for awkward and subdued comedy. The Office had been on the air for a couple years. 30 Rock had just started. It was the year of Seth Rogen and Michael Cera, with the releases of Knocked Up, Superbad, and Juno. However, McKenzie and Clement are from New Zealand, which allowed them distance from their American counterparts. They embraced their outsider status in their characters in order to naively and comically talk about universal topics such as gender, sex, and race that have a much heavier subtext in America.

It might be a stretch to say Flight Of The Conchords are human rights activists when they sing, "Man's lying on the street, some punk chopped off his head/ I’m the only one to stop to see if he’s dead/ Mmm, turns out he’s dead." But that song, "Think About It," can pass as a critique the absurdity of the world we live in. Instead of singing about it from an earnest perspective, Conchords use their humor to make us think. Or perhaps they’re just spoofing overly soulful '70s ballads, which would be humorous in its own way.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Maybe their attempts to resonate with something greater are that much funnier because of their hollowness. One of my favorites from the Conchords has always been "Albi The Racist Dragon," which is not on any of their albums and isn’t a song so much as a musical skit. It's absurd for a labyrinth of reasons, not least of all its use of stop-motion animation to address such weighty subject matter. "Suddenly Albi cried a single tear, which turned into a jellybean all the colors of the rainbow, and suddenly Albi wasn’t racist anymore!" Clement narrates. If only it that's how the world worked. If only crying jelly beans could fix America's problems today. But it doesn't, and they can't, which is why comedic shows with irrational fantasies for healing the world exist.

Flight Of The Conchords is still funny, probably even more so now that I am older, looking back. The jokes have a veil of substance until you realize that they really don’t make that much sense at all. "Hiphopopotamus Vs. Rhymenoceros (Feat. Rhymenoceros and the Hiphopopotamus)" makes me laugh just by typing out its title. The word "motherflippin'" bops out of McKenzie's mouth on the opening verse like the popping off of a Snapple cap, followed by the greatest delivery of the word "horny" that there ever was. It’s a song that soundtracked my friendships of junior high, spending hours outside trying to land the opening rhymes, failing miserably but laughing at our attempts. “Hiphopopotamus Vs. Rhymenoceros (Feat. Rhymenoceros and the Hiphopopotamus)" is also a showcase for what the Conchords did best: making nerdy, antithetical, original songs about pop culture.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Ultimately their greatest songs were quirky and personal rather than broad and political. When they got upset about stupid things, great music resulted. Is "Not Crying" a comment on traditional macho masculinity that asks men to hold their feelings in? Probably not. In the first episode, "Sally," the two get into an argument, more like awkward banter, about Bret turning on a light when Jemaine is hooking up with a woman in their open-spaced apartment. As a result, the woman, whose name is Sally, feels awkward and leaves. One would think the reason why the tension is boiling between Clement and McKenzie is that Sally turns out to be McKenzie’s ex, but all Jemaine is concerned with is that Bret turning on the light scared her away. "I’m not that cool with it," Bret says the next day. Jemaine cuts him off: "He’s cool with it."

After Sally and Jemaine break off their non-existent relationship, he begins to cry. "These aren’t tears of sadness because you’re leaving me/ I’ve just been cutting onions, I'm making a lasagna...for one," McKenzie coos on his own verse. Are they using humor to reveal how universally bizarre heartbreak can be, and then on top of that making heartbreak sort of comforting? Yeah, definitely. So Clement and McKenzie aren’t exactly political activists when singing about dark issues, but that doesn’t mean they’re not stand-up guys making an impact with comedy and music.

It would be easy to dissect every episode's humor and the music that soundtracks it, but that would be an infinite-scrolling essay from hell. Their first EP The Distant Future, released 10 years ago today, makes for a more digestible primer. It contains a handful of Conchords classics including "If You're Into It," "Robots," and "Business Time" and even some live-recorded banter titled "Banter." It was a small glimpse of the two great full-lengths that would follow and of the larger Conchords universe. The TV show itself, though, remains worth diving into. It was nominated for 10 Emmy Awards in 2009 and featured plenty of other stars who would go on to become extremely successful, like Demetri Martin, Aziz Ansari, and Kristen Wiig.

Most importantly, it introduced the world to Clement and McKenzie, two talents who'd go on to do more great work after parting ways with HBO when making the show started to feel like a chore. Clement has since starred in Rio, Men In Black 3, People Places And Things, Legion, and Moana, which birthed a song as catchy and clever as his music with McKenzie. He even made the hilarious and odd What We Do In The Shadows, a mockumentary-meets-horror-flick about vampires. McKenzie has been in the spotlight less often but won an Oscar for his work on The Muppets Movie. And they've continued working together as Flight Of The Conchords, including an appearance on The Simpsons, assorted tour dates, and even an in-progress Flight Of The Conchords movie.

The Distant Future's cover is an image of the two very small men, presumably Clement and McKenzie, standing on the overwhelmingly giant moon. It's a fitting image for a project McKenzie told the NYT was just a happy, aimless result of trying to learn guitar. Two tiny men looking out into the cosmic abyss is an apt visual metaphor for Bret and Jemaine just fumbling around to see what worked, zeroing in on the mundane and the melodrama in the face of an oppressively big universe. "The audience thinks everything is a bit," McKenzie explained. "But often it's not a bit -- it’s just us figuring something out."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]