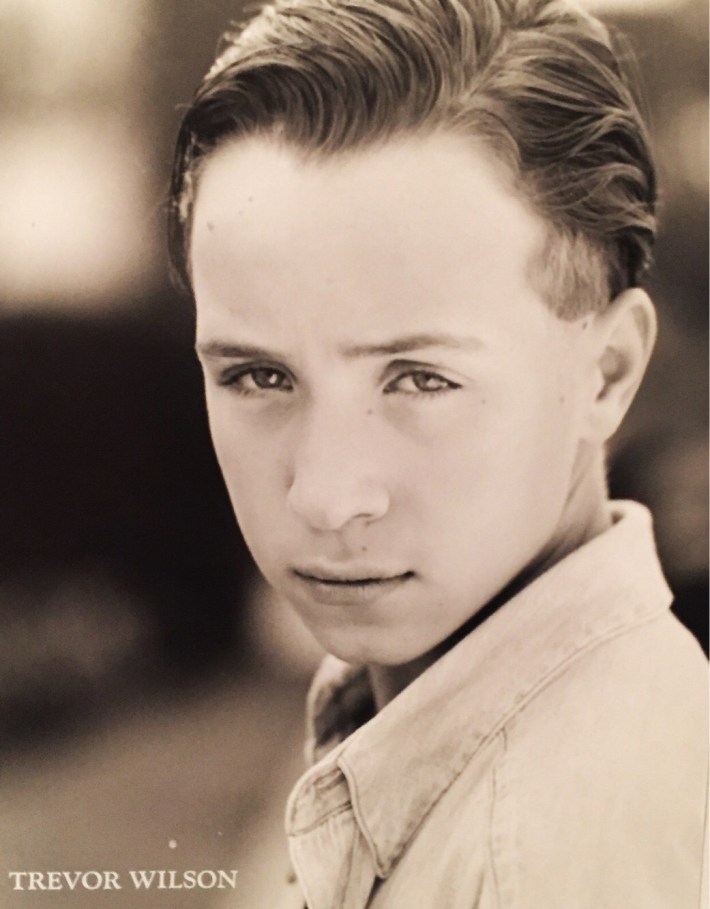

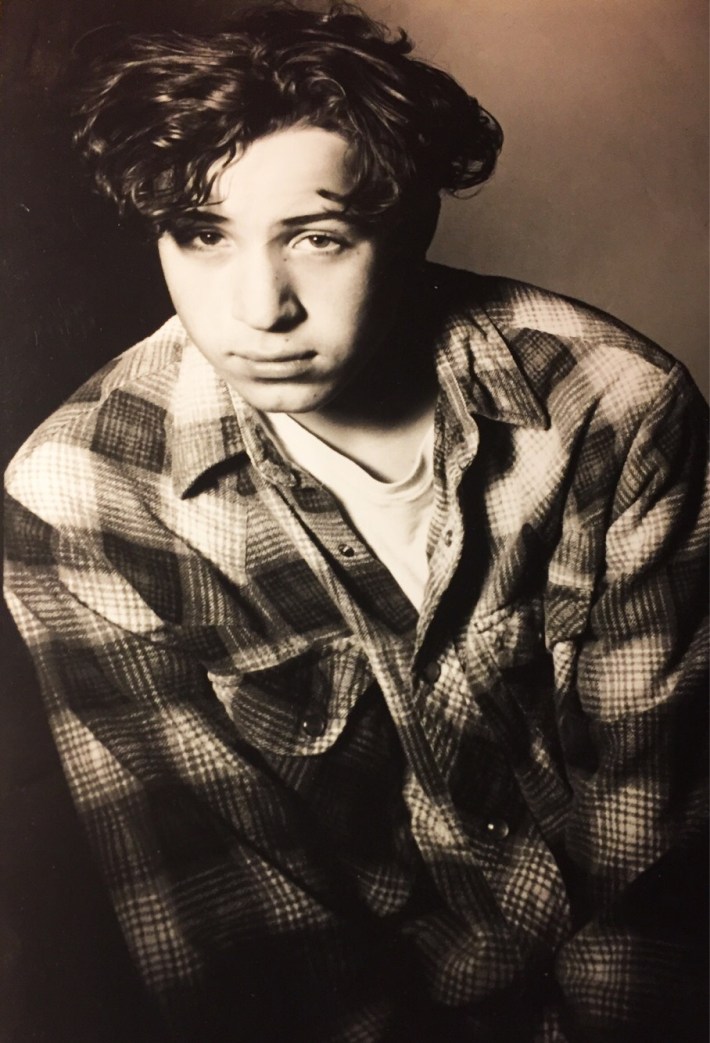

Trevor Wilson was the most iconic face of grunge who wasn't actually in a band. Not even Spencer Elden -- the naked baby on the cover of Nirvana's Nevermind -- was as immediately recognizable a stand-in for the angst and alienation of an entire generation as Wilson became with his first, and only, starring role: as the troubled teen in Pearl Jam's unforgettable 1992 video for “Jeremy.” The Mark Pellington-directed clip became a pillar of MTV’s ‘90s alt-rock canon, and helped the band’s debut album Ten go 13x platinum.

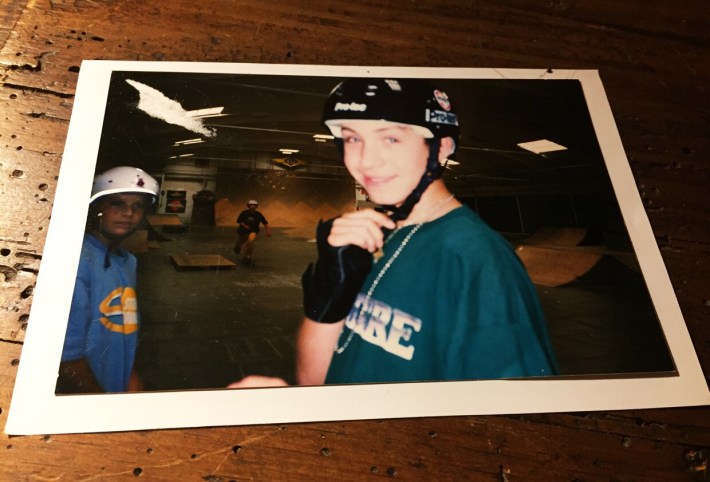

And then he disappeared. Just 12 at the time the video was made, Wilson blew away veteran video director Pellington on his audition tape, despite being sick as a dog on the day he went up against hundreds of fellow kid actors eager to show how they’d tapped into the title character's seething anger and despair. Pellington says he told Wilson to just “look at the camera and don’t say anything” no matter what happened around him. “I just played the song [during the shoot] and you could see something… something changes in the room," the director says of the alchemy he felt watching Wilson channel the title character's desperation.

Wilson's life changed in an instant, from a quiet, literature-loving Waldorf school student in Manhattan to a budding child star in Los Angeles, an abrupt transition he recoiled against almost immediately. "He found that people were attracted to you because you're famous, not because of who you are," says his mom, Diane Wilson. Turning his back on the boxes of fan mail, unsolicited offers from female admirers and potential acting gigs, Wilson reclaimed his privacy and lived a peripatetic life on his own terms for the next two decades.

The last time most music fans of the era likely saw him was with Pearl Jam at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards, after which the gawky teen melted back into the background, focusing on his love of classic literature, and a drive to work on development projects overseas for the United Nations. And then, far from the fake glamour of Beverly Hills, years removed from his 5:33-long moment in the spotlight, Wilson tragically drowned while swimming alone during a vacation in Puerto Rico last August, almost 24 years to the day after the "Jeremy" video dropped.

On the video's 25th anniversary (it debuted on MTV August 1, 1992) and nearing the one-year commemoration of Trevor Wilson's tragic death at age 36, Billboard spoke to his family and the video’s creators about his life. They all described their time with Wilson before and after "Jeremy," and the indelible impression he left on the many lives he touched.

“He was not like everyone else…”

Cinematographer Tom Richmond remembers sitting next to Pellington in the director's Los Angeles home and watching endless VHS audition tapes from New York of kids vying to play the (anti-)hero of the "Jeremy" video. It became pretty clear early into the nearly 200 auditions that the kids they were watching were "typecasty," as if they'd read Pearl Jam singer Eddie Vedder's lyrics about an outcast high schooler -- based on the true story of Dallas 16-year-old Jeremy Delle, who killed himself in front of his classmates in 1991 after years of torment -- and decided they were had the perfect look and attitude for the part.

"In a cliché movie about junior high it would have been the picked-on kid, the outcast who looked funny or strange, and I could tell Mark was dissatisfied with that idea," says Richmond of the parade of odd-looking and over-acting kids they watched, whose performances felt a little too on-the-nose. "[Pellington] couldn't articulate what he was looking for, but he knew he wasn't looking for that."

A few hours in, Wilson's audition came up and Pellington and Richmond looked at each other and said, “That's him!" It could only have been Wilson, Richmond recalls -- ironic, considering the novice 7th grade actor was a mess the day he auditioned.

"He was sick on his tape, and he didn’t play it like, 'Oh, I’m all angsty,'" remembers Pellington, then 30 and best known for his pioneering quick-cut work on the MTV show Buzz and iconic videos like U2's "One." "He was sitting there and I was looking at [his audition tape], and he was kind of dazed and numb and f--ked up. I found out later that he was sick. But he was so expressive, in a non-histrionic way."

Pellington knew that in casting a 12-year-old trying out for his first major role, he wasn't going to get an experienced actor with a bag of camera-ready expressions of rage, internal screaming and tics practiced endlessly in front of a mirror. He was looking for something unique, that spoke to the intangible, vague feeling he was chasing for a video he was approaching more like a short film than a standard lip-synched promotional clip for the fast-rising Seattle band. "He was not like everyone else. He had something wrong with him," the director says.

Trevor had been on a few auditions, but his dad, antique dealer Jim Wilson -- who heard about the opportunity via a casting call in the back pages of Billboard -- says “Jeremy” was different. Sitting in the hallway outside the audition room, Jim Wilson heard someone say “He has to have a good scream,” so he says he pinched Trevor’s leg until his son yelped to get him into character, and also told Trevor a bit of the real Jeremy’s story to help him get in the right emotional frame of mind.

The combination of his illness and his dad's prep made for an audition in which Richmond says Trevor came off as "handsome," but also as someone who was kind of beat-up and not really trying to land the part: "We just went, 'This kid is real.’”

“He was like an old pro, it was almost weird…”

Pellington had already filmed intense footage of Vedder singing the song during a blitz two-day shoot in London. Now it was time to make the "best music video ever" -- according to Richmond, a veteran cinematographer who’d worked on everything from schlock horror movies to Alex Cox’s modern western Straight to Hell. The original plan was to just tell Jeremy's story through Trevor, and not feature the band at all.

Once Pellington had Vedder's searing performance in hand, though, things changed. Now the pressure was on for the narrative to match the live band shots from the English soundstage, and Richmond says the preternaturally mature first-time star brought it from day one.

"I'd done movies with kids before, but Trevor was just 100 percent there -- and focused, and friendly, relaxed and flexible," he recalls of the demanding shoot, during which the shirtless teen had to emote on cue for hours at a time. “I have no idea what Mark said to him, but I don't remember any takes where we said, 'Uh, not that. Let's take a break. C'mon kid, get it together!'"

Richmond recently looked back at his diaries from the shoot and saw notes that made it seem like Trevor was in character the whole time. "He had these looks on his face that were not very kid-like," he says. "He wasn't smiling. No ironic, sarcastic smiles like you'd get from a 12 year-old."

Wilson’s spot-on take on the video’s central character nailed his spiraling anger at being tormented by his classmates, following him as he rages solo in the woods amid intercut shots of Vedder’s intense, close-up performance of the song. The images are indelible: Wilson’s arms raised in a V with a fire raging behind him, sitting listlessly while his classmates laugh at him, and tossing an apple to his teacher as he enters his classroom and appears to pull something from his waistband, a look of calm, peaceful resignation on his face. The original version included a controversial scene in which Jeremy appears to commits suicide with a gun in front of his class, but in an edit that infuriates the director to this day, MTV’s censors demanded that Pellington remove any firearm imagery, which makes the ending -- with an image of the blood-splattered students covering their faces -- more ambiguous.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Richmond says he still can't think of any actor or person who's been as easy to work with as Trevor. "We were shooting our brains out for weird hours, in weird locations in the woods, with some shots where we start crazy close to his face with lights blasting him in the face. He was totally cool with it. He wasn't giggling or [asking for] a candy bar. He was like an old pro, it was almost weird."

He may have been green, but Trevor came by his professionalism naturally. His mother Diane is a macrobiotic cook who has worked as a personal chef and nutritionist for decades for stars including Phil Donahue, Michelle Pfeiffer and director Ridley Scott. She sent her son to study at the world renowned Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute on the weekends, shuttling him in a limo from classes at the Rudolf Steiner Waldorf School in Manhattan on weekdays to her gigs, so they could hang together until she finished late in the evening.

"The movie that was really popular when he was a kid was [1986's] Stand By Me, which got him interested in acting," Diane remembers. "Because I worked a lot, I was always looking for something for him to do that would interest him. And of course I was working with celebrities, and one of my clients’ acting coaches thought Trevor was talented and wanted him to go to her acting class. She asked him continually to come study with her."

Trevor suffered from asthma as a child and Diane -- who was working on location in Chicago during the video shoot -- says his chronic illness may have played a part in how her son looked and felt the day of the audition. She knows one thing for sure: “If I'd been home I doubt I would have let him do that video. With the gun and all that.”

“Hey everybody, this is Trevor. He lives…”

As they would throughout their closely linked lives, Wilson and his mother -- who never officially married Trevor’s dad -- went on an extended vacation together, just after "Jeremy" wrapped, packing into a car for a three-week trip to the Grand Canyon. "I know he was excited when he came to see me in Chicago -- he thought it went well," she remembers of his feelings following the grueling shoot. "He didn't really speak about it much, because it hadn't come out yet."

Neither of them had any inkling about what was about to happen, until a friend of Diane's, a stylist, warned her that this was a big deal. "I had never heard of them [Pearl Jam], but she was excited. She said, 'Diane, this is a really big thing.'”

Indeed, not long after the video debuted that August, the Wilsons quickly discovered just how big a deal Pearl Jam, and the video, were. By then, the family had relocated from Manhattan to Los Angeles, and Trevor was enrolled at Beverly Hills High School, where he seemed to fit in with the children of privilege and celebrity. "Once we moved there, he started getting all this fan mail, and he went on this radio talk show [with Dr. Drew Pinsky] -- and women were calling in and saying they’d like to take him to bed... just boxes and boxes of fan mail," his dad says. "After a few months of that attention, he kind of turned away."

MTV reporter and on-air personality John Norris remembers that heady period well because he was hosting Hangin’ With MTV, a pre-TRL countdown show which featured "Jeremy" almost every day for months on end. “In some ways it really holds up [even] from a 2017 perspective,” says Norris of the then-inescapable clip. “Trevor didn’t overplay it, and a lot of the [emotion] is due to him. I love that he’s a normal-looking kid, not a model, and he gets more imbalanced as it goes on.”

As the video became a hit, Trevor -- a slight, sensitive 120-pound boy -- was recognized everywhere he went, and the glare was not what he anticipated, or wanted. "When you're famous like that, you don't know who your friends are and who likes you for being famous or for who you are," Diane says. "He was going to auditions and decided he wanted to just be a kid. He didn't want to act." Rather than a nightstand piled with scripts, Trevor always had three or four books going at once. He left behind more than 400 paperbacks that his mother has given away over the past year, and nearly as many hardcover books and first editions she’s still sorting through.

The explosive attention on the “Jeremy” video -- which, along with clips like Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and Alice in Chains’ “Would?,” altered MTV’s fundamental DNA for the next half-decade -- had a similar retrenchment effect on Pearl Jam. The band would not make another music video for six years, as a form of retreating from their massive public exposure.

The last time the public saw Trevor in person was with Pearl Jam at the MTV Video Music Awards, in September of 1993, where "Jeremy" took home four awards, including Video of the Year. Wilson, taller and a bit filled-out, was in the crowd with his mom and the group that night, joining them on stage when they accepted the evening's biggest Moonman.

"Hey everybody, this is Trevor, he lives," Vedder said with a smile as he lifted Wilson's hand and patted his young video star on the head, while cradling the final prize of the night. Wearing baggy jeans and a too-big blue t-shirt, the teen shyly grinned and tried to take in the surreal moment, surrounded by the band, with odd-couple presenters the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Tony Bennett just out of view. "The real s--t is if it weren't for music, I think I would have shot myself in the front of the classroom. It really is what kept me alive," Vedder said in his acceptance speech, handing the silver trophy over to Wilson as they left the stage.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The image of Trevor that sticks in Norris’ mind is of later that night at a restaurant in Los Angeles, when the reporter found himself in a booth sitting next to Fleetwood Mac singer Stevie Nicks, across from Vedder and Wilson. “I was talking to him, asking him about the video, ‘Was it hard to do?’ and he was just shrugging, ‘No,’” Norris recalls. “I think he was a bit overwhelmed by it all. But he was not a shy wallflower -- he seemed okay, and Eddie was quite happy to introduce him to everybody.” Norris says even rock icon Nicks seemed excited and intrigued to chat with Trevor, peppering him with questions and making small talk.

Jim Wilson was initially reticent to rehash the story of Trevor’s moment in the sun, because it brings up both a special, mostly happy, time in their lives while forcing him to deal with a loss he still can’t accept. Struggling with a terminal liver cancer diagnosis for the past year, Wilson lives in a cabin in the Adirondacks that's been in his family for 200 years, the same one where he spent time with his son during the winter and summer. It's the home Trevor was supposed to come visit the month he passed away.

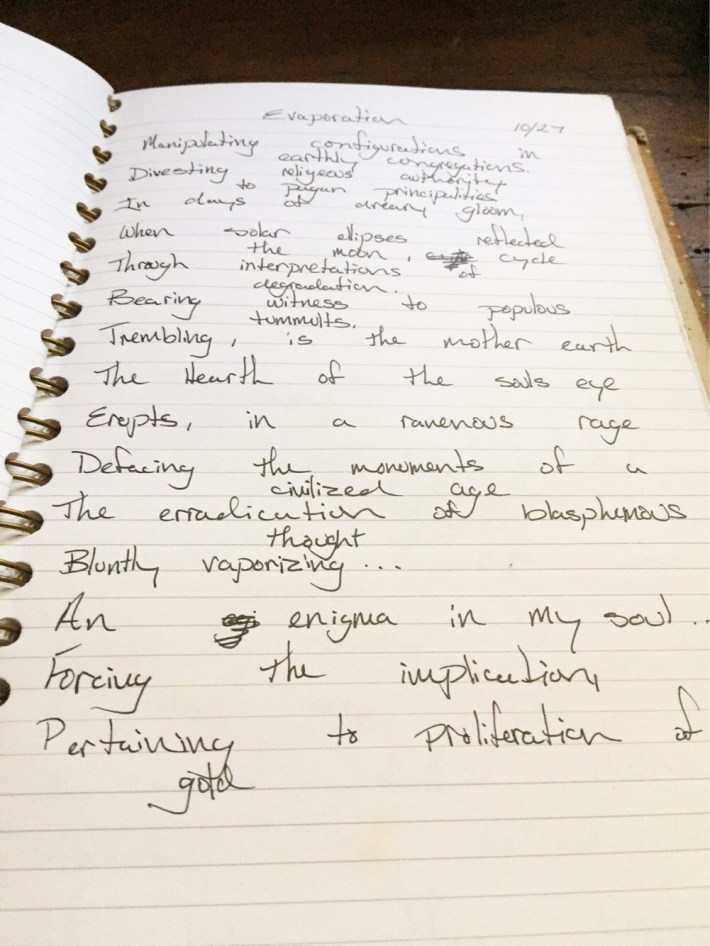

Similarly, still surrounded by her son's poetry, writings and books, Diane Wilson struggled at first to open up, but soon spilled forth with story after story of the fascinating, globe-hopping life her son lived in the years after his insta-blip celebrity faded. "Trevor was a really big part of my life," she says, with what sounds like a smile creeping into her voice over the phone. "We were really close."

“I got the feeling that he was 100 percent an individual…”

Trevor had always been fascinated by international politics, certainly more than tapping into someone else's emotions. He was more of an intellectual than an actor, with a computer hard drive Diane’s just now digging into, filled with the beginnings of novels, poetry, short stories and TV pilot ideas from her only child, who'd struggled with dyslexia in grade school. After their Hollywood years, Trevor moved back to New York with his mom around 1997 to attend the exclusive Dwight School, where he befriended such prep school peers as the Hilton sisters. He ran around the city as any 17 year-old might for a time, trying to anonymously soak up the nightlife alongside a posse of friends who knew his showbiz secret.

Able to afford his share of late nights out, one of the people he became good friends with was Anthony Graneri, a producer of fashion photography who works with renowned photographer Peter Lindbergh. The two met in 1998 when Trevor was 19 and Graneri was in his late 20s, and together they stayed up late like typical New York “party kids,” hitting up then-popular clubs such as Twilo, Limelight and The Tunnel.

One night at Twilo, their crew went to see popular DJ duo Sasha and Digweed, and Graneri remembers that the pair threw on a thumping dance remix of “Jeremy." The gang hoisted Trevor up on their shoulders and the crowd “went completely wild when they realized who he was.” As usual, Trevor shrunk from the attention, as Graneri says that if anyone ever found out about his starring role in the video, it was never from Wilson himself.

Eventually, Wilson enrolled at NYU, studying international relations and logging a six-month exchange program in Rome. While overseas, he fell in love with Italy, moving there for four years and living with one of his longest-term girlfriends, as the two pursued a mutual interest in international economic development. At one point, as moms do, Diane suggested to him that he either needed to come back home and get a real job, or work on his masters.

And so, along with his girlfriend, he applied to the University of Rome and got accepted into a program that led to an internship in Egypt with the United Nations. Trevor stayed for three years doing field work for the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) on development, women's education and -- according to his mom's recollection -- helping to write speeches for then-Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak's wife, Suzanne. "That was the work he'd always wanted to do," Wilson recalls.

“His time in Egypt was among the best times he had in his life, and he would refer back to those days often,” Graneri says. He recalls late-night discourses from Wilson on history, music and philosophy, and one particular story from those days that makes him smile: “Driving through the desert at 120 miles an hour and getting pulled over by the cops, then flashing his UN credentials, and getting an escort from those same cops.”

It's through his beloved stacks of literature, historical non-fiction and poetry -- which would eventually fill the shelves of his three-room Williamsburg loft back home -- that he later bonded with cinematographer Richmond. Though decades older, Richmond went to visit Trevor at his dad’s place upstate a few times. Several years after the shoot, Richmond, then 45, assented to Trevor’s request to meet his mom, waiting with Diane for Trevor to come home from school at her apartment on the West Side of Manhattan.

"Before he came home I started looking around and there were all these books laying around -- Lady Chatterley's Lover -- all these classic college books from the 1800s and 1900s and that's what we ended up talking about: all these books I was supposed to read in college but didn't," says Richmond, who hadn’t gotten to know Trevor that well on the video shoot. "Here's this kid who couldn't have been more than 13 or 14, and he was motivated enough to read these books I couldn't even get through in college."

At some point, Trevor found out that Richmond was a coffee addict and he invited him to meet up in The Village at what he said was the coolest coffee place there was: the nearly century-old Italian cappuccino spot Caffe Reggio. Trevor must have been in his late teens then, maybe 20, and it was the last time Richmond would see him.

“I can’t believe how serious life really is…”

Jim Wilson always worried about Trevor's strength in the water, which is why he says he worked with his son on learning how to swim as a child. "All his life I tried to teach him to swim, because he was a slight boy, and a wave could hit him the wrong way,” says Jim, a concern that would prove prophetic.

Some of that swim instruction took place at the rambling family homestead in Schuyler Falls, New York, where his father's cousin, Rebeca Turner, used to also spend summers. "He was quiet, very quiet, but he'd come up here in the summers when he wasn't with his mom and we'd go camping. He loved the outdoors," she says. "He loved swimming in the swimming holes, and he kind of kept to himself for the most part. But he was very loving with us.”

Turner remembers Trevor as a small kid who loved being outdoors and sneaking into the old grist mill near the river on the family property with her on their way to the upper part of the swimming hole. The last time she saw him was when Jim's aunt Ruth passed away in September 1995, and the family gathered for the funeral, just a few years after the "Jeremy" video. "We walked from the gravesite and went into this grocery store in town, and some kids recognized him from the video and got all excited," she says. (Embarrassed, or just not interested, Trevor kept his head down and didn't talk to the fans.)

As he entered his thirties, however, Trevor looked nothing like the kid in the Pearl Jam video, and people hardly ever recognized him anymore, which was fine with him. He still got some of the perks, Diane recalls, including a promise from the band that any time they came to New York he could get free tickets for life, and hang out with them if time allowed -- a vow they kept until his death. "They've always been so nice to us, and even when Trevor didn't ask in a timely fashion [for tickets], they would accommodate him," she says of the PJ camp.

After bouncing around at a few jobs, including an IT gig that ended when the economy melted down in 2008, and a stint doing production work for a friend's company, Trevor had started sending out job applications again from his Brooklyn loft in the months before his death. He had honed in on getting a U.N. posting in Myanmar, after turning down a chance to get a post in Lebanon.

Looking to clear his head and do some research on Myanmar before he packed up again, Wilson went down to Puerto Rico in July 2016 to relax before his next posting, and sneak in what would likely be his last vacation for a while.

Graneri, who's had an apartment in Puerto Rico since 2003, gladly offered Trevor a list of connections and places to stay while his friend searched for that “a-ha” moment to inspire his next adventure. “A couple of weeks turned into a few months, where he was writing, working on his resume and getting in touch with old contacts,” Graneri says.

With a hole in his schedule, Graneri planned an impromptu trip down last June to hang with Trevor for a long weekend. “It was a Sunday, and me and two of my good friends and Trevor drove out to the mountains to an authentic German restaurant…we spent the day eating there, and then the afternoon on the beach,” he vividly recalls of the last time he saw his friend before that fateful August day. “There’s no special moment per se, but it was just the last amazing day we spent together.”

Diane says Trevor had been doing a lot of soul searching and contemplating in the week before his death. “'Mom, I can't believe I'm going to be 37, where did the years go? I can't believe how serious life really is,'" Diane remembers him saying. Trevor was looking at his still-slim, but now more filled-out body, thinking about how he was getting older and looking forward to the next chapter, and maybe some new business ventures. Before he left New York, he and Diane had begun work on an herbal tea business, along with the home-brewed mead recipe he and a friend were cooking up as another potential side gig.

Trevor had always been his mom's IT guy, and the day he died, she spoke to him 10 minutes before he went down to popular Ocean Park beach in the Puerto Rican capital of San Juan. It was around four in the afternoon and she asked him what to do about a computer hard drive that had melted down. "The last conversation with him he said, 'I'm going in for a swim and then I'll try to meet up with [his cousin] for dinner.' But then I had a feeling, because all of a sudden [his cousin] couldn't get in touch with him, and he didn't answer."

Diane says her son seemed clear-headed that last time they spoke. A week before, however, he'd been swimming with friends when he got swept nearly a mile down the beach. "I think he had a confidence because he rode that wave, and I think it made him feel like he could swim there," she says of the well-known dangers of the riptides in the area. "There were tons of drownings around there, and my mother told him, 'Trevor, be careful, I can't tell you how many times I got knocked down.'"

From what Diane has been told about her son’s August 7th death, a man who was on the beach with his two children -- who had just finished his lifeguard training -- saw Trevor's pink and orange bathing suit bobbing in the water and swam out to save him. The man worked on Trevor long enough to get a heartbeat, but then the EMS crew that arrived wasn't able to keep him alive.

Trevor had been staying with Anthony’s friend Diana in San Juan at a house just half a block from the beach, and Anthony says he's heard the conditions were not particularly challenging that day. The ever-present danger -- which Graneri feels is often played down to avoid spooking the thriving tourist trade in the financially strapped country -- was still there, though. “One of the things about Trevor’s spirit is you couldn’t tell him anything,” he says.

Asked why there was a curious lack of reporting on Trevor’s death in the local or international press given his semi-celebrity -- news of Wilson's passing didn't even seem to make it to the States, aside from Pellington mentioning his drowning during a "Jeremy"-related interview on the Celebration Rock podcast in March -- Graneri chalked it up to the financially strapped Commonwealth's infrastructure issues. “It took us an entire day to find out where his body was,” he says.

Estranged from her ex at the time, Jim says Diane didn't tell him about Trevor’s passing for nearly a month. He fell into a deep depression when he eventually found out, and recently began attending grief counseling workshops for parents who've lost a child. Jim hadn't watched the "Jeremy" video for many years until one of his granddaughters brought it up on an iPad this summer, and it broke his heart all over again. "It just shocked me, realizing that he's gone," he says.

Diane says she spoke to Pellington in October and they discussed Trevor's poetry, after which the director said that Vedder was interested in possibly writing a song based on one of Trevor's poems some day. "I started going through his stuff and I came across a letter he wrote to me when he was going off to Europe to get his masters, and it crossed my mind to let Eddie look at it and see if he wanted to do something with it," she says. (The band could not be reached for comment for this story.)

Like Jim, Diane is still struggling to emerge from the fog of grief a year later. She has a kind of peace, though, in knowing that even if the EMS crew had been able to revive Trevor, he likely wouldn't have been the same. "I can only say that knowing Trevor and how sharp his mind was, and how smart he was, he would not want to be alive not having all his faculties," she says.

After Pellington's conversation with Diane, he reached out to the band and Vedder texted him back right away, asking for Diane's number. "I said to [Vedder], 'If you ever want to make something or do a song or try to honor him in some way, I'm in.”

Over his ensuing call with Trevor's old co-star, Pellington says the men discussed being parents, their sadness over Trevor's passing, and loss in general. "I grew up on the Jersey Shore, Ed grew up in the ocean as a surfer... so with Trevor drowning, it connected on a lot of abstract levels," Pellington says.

Diane, not yet ready to dig deeper into Trevor’s belongings, has yet to get in touch with Vedder. "When you're 12 years-old your life could go anywhere," she says, thinking back on her son's unusual journey. "I had said to him, 'I've always supported you going wherever you wanted to and I know you have to go, but do you really have to go so far away?' But I would never stop him from going [to Myanmar], that's where his life was taking him."

"I have to think it was his time to go no matter what," Diane now says of her son’s death. "Passing that way was very peaceful, and he was doing what he loved and was very happy, which to me is the most important thing.”

She calls back to a memory from years earlier, on a vacation in Hawaii that she took with Trevor and his maternal grandmother. Trevor, not a "daredevil or a thrill-seeker," nonetheless seemed determined to swim at a spot clearly marked: "Danger: No swimming."

"I told him, 'I can't come in and get you,' and he was upset that I got so frightened," Diane remembers. "But he went in anyway, and wasn't afraid."

This story originally appeared on Billboard.