Sixteen years before we elected the most embarrassing president in US history, we elected the second most embarrassing president in US history. The climate of idiocy surrounding George W. Bush’s time in office earned its own word: Bushisms. The infamous "Fool Me Once" speech; the Mission Accomplished banner brought out for a mission that to this day has not fully been accomplished; the inability to pronounce the word "nuclear" despite the fact that he was supposedly determined to hunt down nuclear weapons in the Middle East. It was during his presidency that the whole meme about Americans not being able to point to the Middle East on a map resurfaced, a legacy of the war his own dad waged in the early '90s. But beneath all of that seemingly insurmountable foolishness was something much more sinister; in the eight years the Bush Administration led the nation, the US launched the War On Terror, invaded Afghanistan and then Iraq; Katrina, the NSA, Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo. There were calls for impeachment, so please: Shut the fuck up about his puppy paintings.

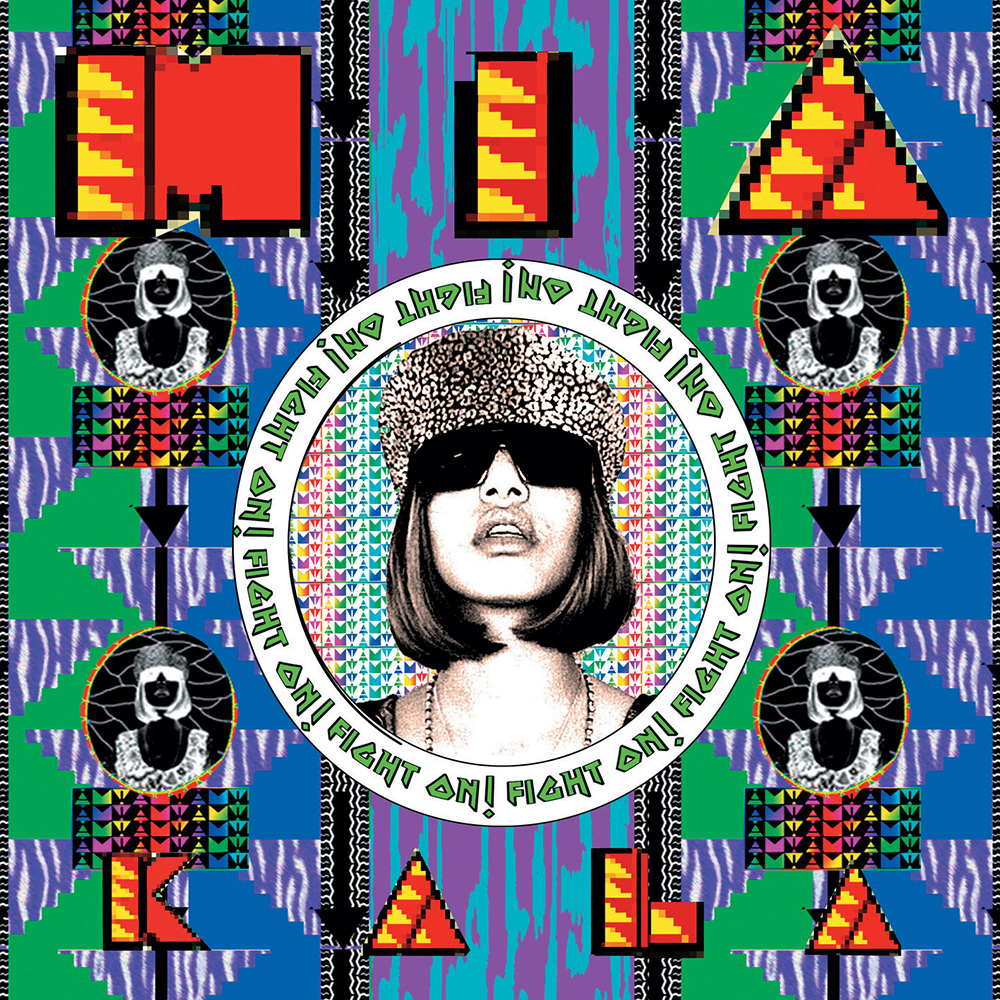

Post-9/11 America was fueled by intense paranoia cloaked in patriotism. People were angry and afraid and our government harnessed that to found Homeland Security and put its citizens and any foreigners perceived as a threat on watchlists. It’s within this particularly reactionary period of American history (one that we definitely haven't left behind) that M.I.A.’s sophomore album, Kala, which turns 10 this weekend, was released. It was the album that propelled her to stardom almost entirely based on one especially catchy sing-along that, on a surface level, was all about globalization and smoking weed.

M.I.A. didn’t intend for "Paper Planes" to become a generational stoner anthem, and the drama behind the scenes of Kala is what gave initially lighthearted dance songs their heft. "Paper Planes" was one of the last tracks she wrote for Kala and one of the first she was able to record in the US once the government finally let up and granted her a visa. After her debut album, Arular, came out in 2005, M.I.A. was temporarily placed on the Homeland Security Risk List due to the political nature of the album and the fact that M.I.A.’s dad, for whom the album was named, was a Tamil activist in Sri Lanka associated with the Tiger Rebels. If you listen to "Paper Planes" with this in mind, it becomes a song about fearing the other. In it, M.I.A. plays the role of the immigrant the powers that be insisted (and continue to insist) we should fear: the one smuggling drugs and guns and stealing jobs from the existing quote-unquote hard-working (read: white) Americans. Knowing this makes that chorus of kids in Brixton singing along to the sound of gunfire, that "Straight To Hell" sample, that cash register cha-ching, so gratifying. "Paper Planes" capitalized on the same paranoia that tried to stunt the creation of Kala. The song peaked at #4 on the Hot 100 and it remains one of the most subversive pop songs to crack the top 10.

The ubiquity of "Paper Planes" is best described in pop culture nods. Pineapple Express basically adopted it as a theme song; T.I. sampled it as the intro to "Swagger Like Us," which featured Kanye, JAY-Z, and Lil Wayne; Rihanna covered "Paper Planes" in Milan; the song soundtracked that crucial train montage in the Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire. "Paper Planes" was big when it first came out in 2007, and its popularity magnified by 2009, when a very pregnant M.I.A. performed the intro at the Grammys in a patchwork of checkerboard and mesh. This was M.I.A. as polarizing celebrity, the woman who would be called out for eating truffle fries she didn’t order, who would eventually do a hypocritical recycled clothing campaign for H&M, a company that outsources most of their fabrication to Bangladesh. But whether or not M.I.A. practices what she preaches is a conversation for another essay; when "Paper Planes" first came out, M.I.A. was the coolest rebel around, a female rapper making dance music that sounded-off to far corners of the world.

Kala was originally supposed to be helmed by Timbaland, but when M.I.A. couldn’t secure a visa, her only alternative was to pick another place to record an album. Instead of choosing to stay in her native UK like she did for Arular, M.I.A. globe-trotted. The bulk of Kala was produced by herself and Switch, in Trinidad, India, Jamaica, Australia, and Liberia. M.I.A. ended up in these countries in pursuit of new sounds to integrate into her already signature rapid-fire, compulsive production. Blaqstarr and Diplo both contributed to the album at different points on M.I.A.’s journey, but all of her producer’s influences are footnotes of the greater story. In an interview, M.I.A. likened Kala to a layered cake. "Every song has a layer of some other country on it. It’s like making a big old marble cake with lots of different countries and influences. Then you slice it up and call each slice a song."

And the result is an album that promotes a global conscience not easily heard in a lot of popular music at the time. It was a dance album that confronted the hegemony of a market largely dominated by quote-unquote Western forms. The production on the first three tracks on Kala integrates the voices of kids on a playground in England. Songs like the playful middle track "Mango Pickle Down River" features the indigenous Australian rap group Wilcannia Mob who were teenagers at the time of recording. On "20 Dollar," M.I.A. sings the entire chorus of Pixies' "Where Is My Mind" at a slowed-down tempo after telling a few stories about the effects of global poverty. The grime rapper Afrikan Boy appeared on "Hussle" -- a song that’s explicitly about the immigrant experience -- years before grime penetrated the US market. M.I.A. had her finger on a pulse that spanned nations, and she figured out a way to harness disparate influences into a singular style that could thrive in various markets.

"Paper Planes" is the song that made Kala, but one of the album's best is a track called "World Town." It's a stuttering call-to-arms that builds and builds and finally breaks down on a unifying chorus. "Hands up!/ Guns out!/ Represent/ The world town," M.I.A. chants over the recognizable sound of a rifle cocking that easily blends with the hand-clapping beat. It's a song that, in its roundabout M.I.A. kind of way, asks listeners to take the side of the disenfranchised, to reject patriotism and nationalism and become global citizens. And what better way to bring people together, really, than on the dance floor? For those who were out in the streets protesting Bush's various misdeeds, there's comfort in declaring yourself a member of a larger army.

Ten years on, Kala continues to ask a bloated question: What is world music? Is it music that uses non-Western instrumentation or is just anything that isn’t sung in English? Or is it just music made by the other? Kala was simultaneously labeled "world music" and "dance music" and "rap." It was an exciting mix of genres that left a lot of people totally delighted and totally confused. And in turn, M.I.A.’s otherness became her brand; she thrived on the fear a lot of Americans felt toward anyone who spoke of radicalism at a time when that could land you on a blacklist. M.I.A. wanted to be a rebel, and thanks to the increasingly hostile politics of the era, she had something to rebel against.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=HBECisSkAu4

https://youtube.com/watch?v=wcN1i6Qcjxg