You guys ever see that Wilco documentary I Am Trying To Break Your Heart? I love that flick, but there's one scene in particular: Wilco are in the studio, recording what will eventually come together as their 2001 masterpiece, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, and the late Jay Bennett is explaining how they're developing the track "Poor Places" using ambient noises, clattering rhythms, and found sounds. Says Bennett:

A lot of times when you're playing, if you don't have any, like, sonic landscape behind you, everything turns into a folk song. We wanted it to not sound like a little folk ditty. We wanted to have some kind of sonic weight under all of that ... something kinda weird and fucked up.

Next thing you know, Bennett is on the floor in front of a Les Paul that's propped up on a stand. He's crouched low, like an auto mechanic or a shaman, holding a whirring electric egg beater an inch or two away from the guitar's fretboard, generating a thick atonal hum. "You put 'em together," Bennett says of his chosen tools, "and you'll get some really magical moments."

Here's the scene I'm talking about. You should check it out.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=854yNi1HIq8

Watching that footage absolutely blew my mind: witnessing all that energy and experimentation dedicated to creating sounds that most people won't consciously notice or understand when they listen to the song. And it's especially wild to watch that and then listen to the song as it appeared on the album. Do that, too.

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is a masterpiece in no small part because of those sonic landscapes -- even when they blend into the background, as often happens with landscapes. And without those sonic landscapes ... I mean, the album might still be a masterpiece, but it wouldn't be the same album. The songs might be similar, but you'd hear something totally different. When I saw that scene, it literally changed the way I experience music, maybe the way I experience reality. Prior to seeing that, I assumed "the song" was a core thing, and "the sounds you hear when you listen to the song" were superficial or ephemeral things. After seeing that, I realized none of my beliefs were real. There was no distinction: There was one thing, and that one thing was made up of many things, and when I listened to it, my experience as a listener became part of the thing, too.

The Taoists call this perceptual paradox Taiji, which roughly translates as "supreme polarity" and is most commonly illustrated in the philosophical concept of yin and yang. A simple example of this is, like, when you see an object and its shadow. Your brain delineates these things as "an object" and "a shadow" -- but they're entirely interdependent and only exist like that in your perception in that exact moment. Does that make sense? No? Lemme try again.

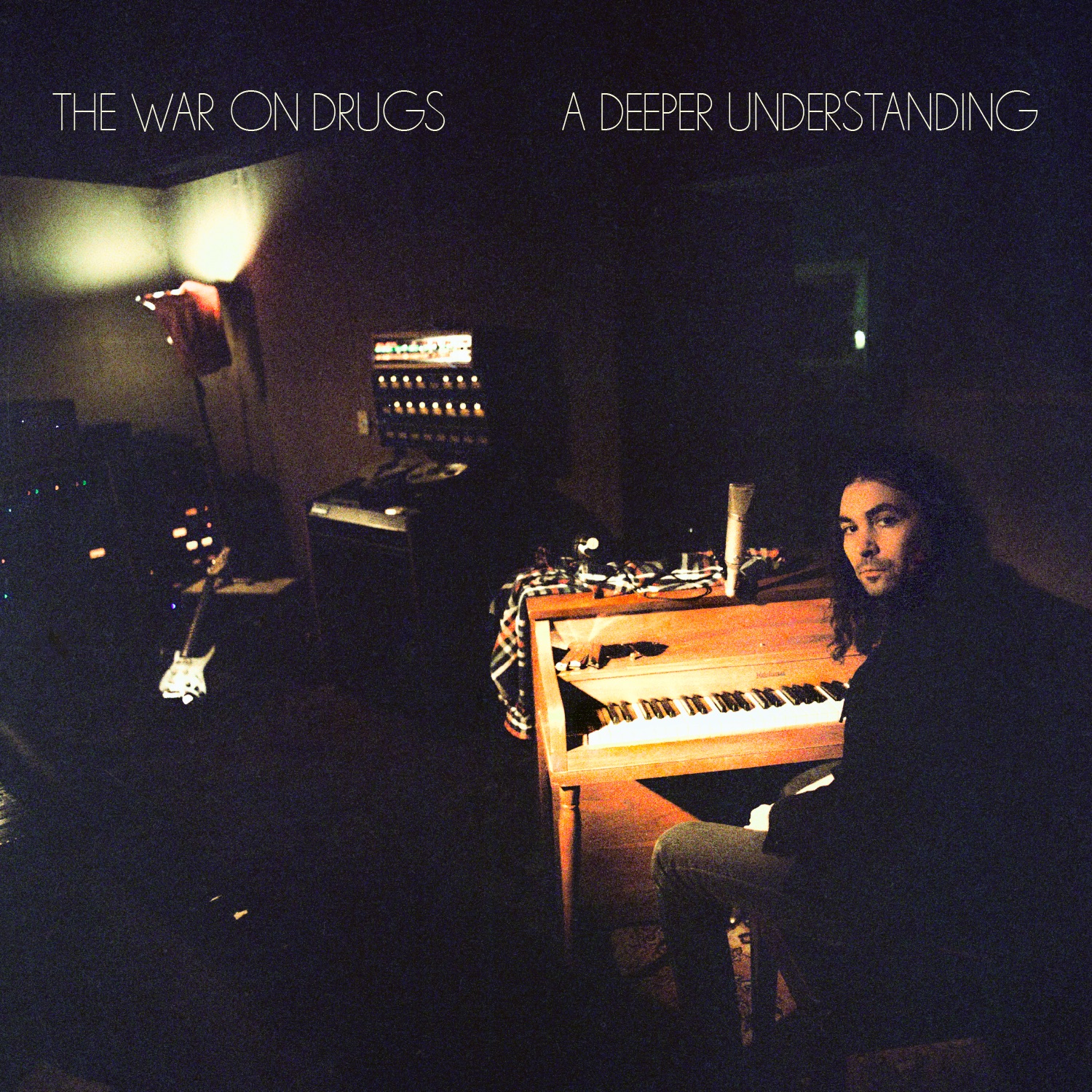

The War On Drugs' fourth full-length, A Deeper Understanding, opens with a song called "Up All Night," and "Up All Night" opens with a pair of incongruous sounds: (1) a paper-thin drum loop that seems like it could have been programmed on a Yamaha DD-5 that somebody bought at a garage sale in 1990, followed immediately by (2) a reverb-washed synth plinking out a minor-key progression that might pass for a sample from Don Henley's Building The Perfect Beast (1984), or Phil Collins' No Jacket Required (1985), or Steve Winwood's Back In The High Life (1986).

Both these sounds belong to bygone eras, but they don't belong together. There's something odd or off about their confluence; their respective tempos or textures don't quite match up. There's a very particular percussion sound that should accompany those synths: brushes tastefully tapping away on a snare; a touch of hi-hat; maracas, maybe. The drum track you're hearing instead sounds like a placeholder from a home-recorded demo of an entirely different song. It's jarring. And that aural dissonance can result in a kind of cognitive dissonance. If your ears function like mine, they follow the melody -- the keys -- and push away the percussion.

By the time the song hits its stride, though, its entire bone structure seems to have morphed. The '80s AOR synths are a submerged hum. The beat, meanwhile, is bigger, harder, louder: a motorik pulse sharing the spotlight with War On Drugs frontman-auteur Adam Granduciel's late-period Dylan-esque vocal. From there, things only get weirder. If you were to randomly let the needle drop anywhere in the middle of "Up All Night," you might mistake the song for a mid-'90s avant-indie record. Something off Electr-O-Pura, maybe. Or Transient Random-Noise Bursts With Announcements. Or The Sea And Cake. Or Washing Machine.

You don't do that, though. You drop the needle at 0:00, you hear that synth, and you think, "Sounds like Don Henley. Or Phil Collins. Or Steve Winwood." And maybe you never shake that impression. It's easy to get snagged on that hook, partly because it announces itself so immediately, with such clarity, and partly because that's the only friggin' hook on this whole stretch of highway. "Up All Night" handily clears the six-minute mark, and the most prominent instrumental tone throughout is feedback. There's one section here that sounds like a small free-jazz/noise ensemble trying to recreate the visceral effect of a July sunshower using, I dunno, a bassoon, a xylophone, and assorted other tools. And that is a breathtaking bit of music, to be sure, but that's not a hook. That's also not much of a narrative. So that's not what people talk about when they talk about the War On Drugs.

I suspect that sort of selective hearing is at the root of most people's misperceptions of the band, irrespective of their feelings about the band. Let me give you a couple examples to illustrate:

- "War On Drugs. Due to all of the fuss, I checked out your [music], and I called it right [when calling it "beer commercial lead-guitar shit"]. You sound like Don Henley meets John Cougar meets Dire Straits meets "Born In The USA" era Bruce Springsteen. It's not a criticism, its an observation." -- Mark Kozelek, by way of blatant insult

- "[W]hile Mr. Granduciel may be a reluctant savior of rock culture, commercialism and bombast ... he is a careful steward of the sound, an obsessive studio rat in constant search of the authenticity he sees in titans like Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and Neil Young." -- The New York Times, by way of lavish praise

I think both those takes are (A) the same, and (B) wrong. I think people who say that kinda stuff about the War On Drugs are hearing it wrong. I think they hear the one big thing, assume that's the thing, and tune out everything else, like everything else is either accidental or incidental. But it isn't. Everything else isn't even everything else. It's everything. That's the song. That's the thing I'm talking about. Taiji.

Adam Granduciel embodies this Taiji principle in a whole bunch of ways. For instance: In the War On Drugs, Granduciel serves as both the Jeff Tweedy figure and the Jay Bennett figure. The yin and the yang. Furthermore, the War On Drugs is at once both a solo project and also a band. (Seriously, I've read the one-sheet for A Deeper Understanding a half-dozen times and I still can't figure out who contributed, what they contributed, or when they did so, but I do know that Granduciel basically drafted and obsessively worked-over every second of the whole LP.)

Somewhat fittingly, Granduciel first came to prominence playing the Jay Bennett role to his own personal Jeff Tweedy: Philly icon Kurt Vile. In fact, Granduciel's credits on Vile's 2008 LP, Constant Hitmaker, weirdly mirror Bennett's on "Poor Places," right down to their respective "noise" contributions. (The comparison is strictly musical, however; by all accounts, Granduciel and Vile have a much better relationship than did Bennett and Tweedy.) The two men hooked up in 2003 working together on Vile's songs, and in 2005, they formed the War On Drugs. Granduciel continued playing in Vile's band till 2011, but Vile left the War On Drugs after their first LP, 2008's Wagonwheel Blues. That record's title is a bit of a misnomer: Wagonwheel Blues is by no stretch a "blues" album. It's also not much of a War On Drugs album. It's basically just a decent indie-pop album.

In 2011, the War On Drugs released their second LP, Slave Ambient, and it's there that you can really hear the emergence of Granduciel's artistic voice. Slave Ambient isn't an ambient album, per se, but there are plenty of ambient elements giving space and shading to the anthemic stuff. Slave Ambient is a pretty great album.

In 2014, the War On Drugs released their first towering instant-classic LP, Lost In The Dream. That album ... man, you don't need me to tell you about that album. Lost In The Dream came in at #2 on Stereogum's year-end list and occupied the same spot on my own list, and it just as easily coulda been #1 on both. This is what our very own Ryan Leas wrote about that album at the close of 2014:

[Lost In The Dream] sounds very much like the Pennsylvania in which it was created, with all the state's crumbling factories and formerly-grand-now-decrepit stone buildings: some strange psychedelic portrait of Americana and memory. This is what a hundred rides down a highway sound like when you're loaded down with the perceptual mess of decades of highway mythology. This is what a classic American record sounds like in 2014. It'll stick around.

Lost In The Dream created all sorts of opportunities for the War On Drugs, including (but not limited to) a leap from an indie label, Secretly Canadian, to a major, Atlantic Records. Fun fact: Atlantic is owned by Warner Music Group, and it's not inconceivable that Warners' infamous fumble of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, as documented in I Am Trying To Break Your Heart, played some role in Granduciel reaching an agreement with Atlantic. As the Flaming Lips' Wayne Coyne told Greg Kot about the label's post-YHF approach to artist development:

We are benefiting from the label's regret over Wilco. We are living in the golden age of that being such a public mistake. The people on Warners said, "we'll never have a band like Wilco feel we don't believe in them again."

Which, coincidentally or not, nicely aligns with the recent account given by Granduciel to The New York Times:

It's like an indie-rock deal with a major ... It's two records for Atlantic, full creative control. What more do you want?

Whatever the case, A Deeper Understanding sounds like a major-label debut in the best possible sense. In fact, considering the diminished profile of major labels over the last decade or so, it almost feels like a throwback: a momentary return to the boom years, when an established indie act would jump to a major and summarily blow through their entire advance making an unapologetically massive album if for no other reason than to justify the entire endeavor of having made the jump. Needless to say, that course of action resulted in plenty of embarrassment and/or heartbreak back in the day, but on those remarkable occasions when it came together exactly as it had been drawn up? I'm talking about, like, Elliott Smith's XO. Or AFI's Sing The Sorrow. Or Stereolab's Emperor Tomato Ketchup. Or Trail Of Dead's Source Tags & Codes. Or the White Stripes' Elephant. You know what I'm talking about. And you know that most major label debuts don't go that well, but when they do?

That's the kind of leap Granduciel is making here. A Deeper Understanding is the War On Drugs' second towering instant-classic LP, and their best album by a distance. Right now, it's my favorite album of 2017, and I'll be pretty surprised if I'm not saying the same thing come December or a decade after that.

It's not like Slave Ambient and Lost In The Dream lacked for ambition, but A Deeper Understanding goes further in every direction and bigger in every capacity. The production is cleaner and the mix is more refined. There's a clarity here that gives every sonic element some space and room to breathe. The songs are expansive but the compositions are taut and thoughtful. Spend some serious time with A Deeper Understanding and you'll see how carefully these songs were put together, how the pieces fit, how every section complements (and is complemented by) the surrounding sections and the greater whole. You'll see Granduciel's intention.

But you don't even need to spend serious time with it, honestly: Play it loud on a long drive, or soft in the background at home, and you'll feel everything. Granduciel has plenty of gifts, but the one that makes his songs stand out is his ear for arrangement. He knows how to maximize space; he's comfortable letting a quiet moment linger, and he's confident taking unexpected turns, using shifts in momentum to produce a body high in the listener. Then, when he hits you with one of his hooks -- the best punch in his arsenal -- you see stars. In that respect, A Deeper Understanding is an absolute hit factory, even by the War On Drugs' impressive established standards. If you're partial to Granduciel's hooks (and what kind of monster isn't?), this thing is gonna knock you the fuck out.

In theory, that squares nicely with the archetypal "major label debut" narrative, but in practice, that's where the whole thing goes haywire. There's an old music-biz cliche -- known all too well by every guitar-wielding band that made the indie-to-major jump in the '90s -- about the new album's "single," or lack thereof. It was immortalized in song by none other than Tom Goddamn Petty:

Their A&R man said, "I don't hear a single."

That's the cruelly ironic conclusion of Petty's 1991 hit "Into The Great Wide Open" -- the point in the song at which young rock hopeful Eddie is washed out of the industry and left to a wide-open future in, I dunno, warehouse management or film production or whatever. Now, the game has changed a whole lot since '91, and Adam Granduciel absolutely doesn't have Eddie's problems. Yet, somehow, Atlantic has released FIVE singles from A Deeper Understanding -- that's half the album, which isn't out for another week -- and it's possible that the five songs they HAVE NOT released are, in fact, the best, most obvious choices for singles.

Now, I wanna be real clear about this: Every goddamn track that's been released in advance of A Deeper Understanding is FUCKING INCREDIBLE. You've heard them; you know this. And I know that. I just don't want to give the impression that I don't love these songs, because I do. I love them all. They sound amazing outside the context of the album and even better when they're sequenced together as parts of a whole. I'm just saying, they somehow suggest the album has fewer hooks than are actually on there. Let's go down the list of the singles (so far):

Single #1 - "Thinking Of A Place"

So ... yeah. This track is 11+ minutes at a Mazzy Star tempo and the big hook comes around the 6:40 mark, just after the dusty pedal-steel lick. I like to imagine Granduciel exercised his "full creative control" to force this one out as the lead single. I also like to imagine a boardroom full of Warner Music Group execs hearing this one for the first time, sitting in uncomfortable silence for those 11+ minutes, staring at random points around the room, wondering who was gonna get the axe when those 11+ minutes came to an end.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=TeaDE1magRk

Single #2 - "Holding On"

Credit where it's due: Here we have a legit banger that at least sounds like a single even though it's nearly six minutes long. I like to imagine Granduciel's A&R begging for this one. "Adam, this is my JOB we're talking about. We will absolutely, definitely do 'Up All Night' at some point, you have my word, but you gotta work with me here. Seriously. Please."

https://youtube.com/watch?v=6-oHBkikDBg

Single #3 - "Strangest Thing"

OK, I guess I can kinda see making a case for "Strangest Thing" as a single, too. It's the fourth song on the LP, and it's the moment the whole thing first clicked into place for me. I wrote a long-ass review of this track the week it dropped -- a Premature Premature Evaluation of A Deeper Understanding, if you will -- and in retrospect, I'm thinking I should have just put that piece on ice and used it here instead. But I couldn't wait! And now I'm paying the price. Anyway, at 6:42, "Strangest Thing" is never gonna make much of an impact at radio, and its streaming numbers are probably a little less than robust, too, but if fans weren't sufficiently hyped by Singles #1 and #2, this is the point at which they hit the "pre-order" button and rung up some sales. I like to imagine Granduciel's A&R seeing those numbers, exhaling audibly while printing them out, and running them up to the boardroom for the Warner execs to look over during the next meeting. Nice work, everyone.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=bvmEYgFsgyg

Single #4 - "Pain"

GRANDUCIEL'S A&R TO GRANDUCIEL'S VOICEMAIL: "Ad-Rock, what's good? Bro, remind me to show you the pre-order numbers that came in after 'Strangest Thing.' We are on a roll here, bud! Thing is, all the singles so far have been kinda, I dunno, long? In the context of them being singles, I mean. They're all perfect, don't get me wrong, but I'm thinking, like, just in terms of listeners' attention spans and stuff? I think it would be a good look if we just hit 'em with one of the shorter songs, a legit old-fashioned radio-ready rock 'n' roll single. Remind me: Which were the shorter songs again? Whatever, text me when you get a chance and let's do this. Peace!"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=z_qaKlf2TzU

Single #5 - "Up All Night"

WARNER EXEC TO GRANDUCIEL'S A&R: "Well that last single was kind of a snooze, but this is something. You know what this reminds me of? Don Henley. Or Phil Collins. Or Steve Winwood. Say that reminds me. Did I ever tell you that Roll With It paid for my yacht? True story! It was...'88? I think it was '88. The point is... [Tells yacht story for the millionth time while song dissolves into epic-length ambient-noise dreamscape in periphery.]"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Dj_eFigyvQ8

In fairness, I am not a thousand-percent confident about the accuracy of my portrayal of the modern-day major-label office environment, but I present this not to illustrate the behind-the-scenes operations of a music-purveying corporation, but to emphasize how fucking good the rest of the album is -- seriously, no sales-minded person would pick "Pain" for a single before "Knocked Down" or "Nothing To Find" or "Clean Living," because those songs are hits. But, also, they're not. The above scenario should also illustrate to you just how fucking crazy it is to try to sell the War On Drugs to a mainstream audience. Listen to me: The biggest hook on A Deeper Understanding -- and it is an ABSOLUTE MOTHERFUCKER -- is in the song "In Chains." As such, "In Chains" should definitely be a single. "In Chains" is an incredible song. But "In Chains" is more than 7 minutes long, and that hook comes in at about 2:40 -- at which point, I go lightheaded like I just took a huge nitrous blast -- and then it never comes back.

So tell me: How the hell is that gonna work as a single?

Thing is, while indies typically sign artists based on stuff like personal taste and brand aesthetic, major labels tend to prefer albums that can be easily and cleanly classified by genre (there are a bunch of reasons for this, all of them related to marketing strategies, but it's primarily because radio formats are almost suffocatingly rigid, and radio play is still the most effective medium for reaching listeners.) I get the indication Atlantic is hoping the War On Drugs will be filed under "rock," based on a small sampling of available evidence. Consider: The first sentence of the label's one-sheet bio refers to A Deeper Understanding as "a testament to the ambitious art of album making and modern rock and roll." The most recent PR materials sent to media outlets lead with this pullquote from The New Yorker: "The War on Drugs is, to my ears, the best American 'rock' band of this decade; it is certainly the one that makes the genre feel most alive."

But it's really not a rock album. It's WAY too adult-contemporary to be rock. And it is WAAAAY too weird to be adult-contemporary. It's too soft to be alternative, too hard to be folk, too outré to be AOR, too auterist to be jammy, and it has too many retro synths/noise assaults/shoegaze glides to be country. It has elements of all these genres (and others), but never definitively embodies any of them; it just uses them where they'll best aid the individual song's intended effect on the listener. To the extent I'm able to come up with any sort of classification, the only overarching tag that even sort of applies is "post-rock" -- but in 2017, major labels don't sign post-rock bands.

So: Adam Granduciel is a writer of god-level hooks who can't write a true single, and yet his new album has generated five singles, none of which contain the very best of its author's god-level hooks. Also: The War On Drugs are a rock band that doesn't play rock music and is not a band. And yet they do, and they are. Taiji.

This is an opportune moment to underscore that last point. The War On Drugs do play rock music. Or, at least, the War On Drugs' music sometimes resembles or references rock music, which is an approximate equivalent of playing rock music. It's not Appetite For Destruction or Exile On Main Street or Zep 4, but it's also not as if everybody who's selling, buying, re-packaging, and re-selling the whole "reluctant savior of beer-commercial bombast" thing is hearing something that absolutely isn't there. It's there! It's there in Adam Granduciel's singing, which cribs directly if not solely from Dylan (an artist who, if we're being real here, is primarily identified as a folk singer, but, y'know). It's there in Granduciel's melodies -- and ESPECIALLY those gigantic hooks -- which absolutely owe a debt to Springsteen. It's there in Granduciel's guitar solos, which don't occur as frequently as you'd expect from a quote-unquote rock band, but they're in there, sometimes echoing Dire Straits' Mark Knopfler, sometimes Neil Young with Crazy Horse. It's there in Granduciel's harmonica solos, which, again: Dylan. All those people are not only icons but geniuses, of course. And if you hear all those people, you can comfortably throw in hit-making sub-genius types like Petty or Mellencamp because, like, where the fuck do you think Petty and Mellencamp came from?

When Granduciel does reference rock, though he's calling back a very particular moment in the genre's evolutionary history -- roughly '81 to '88 or so. The Reagan years. And that was a pretty weird period for rock music! It gave us some of the best bands of all time (including the single greatest musical combo ever to share precious oxygen with this boorish, repugnant, altogether-unworthy so-called civilization). But Granduciel isn't drawing a damn thing from those bands. He's calling back to rock giants, not at their peak, but the era after their peak -- when they were adding synths to their arrangements to keep up with the technology and trends of a new decade; when their old fans were entering their 30s, becoming parents, carting around little kids in station wagons and sedans; when MTV was an emerging force, increasingly altering the landscape and ecosystem; when compact discs were replacing vinyl LPs, and record stores were becoming record-store chains, and major labels were flush with all this new revenue.

Granduciel is sifting through a pile of dinosaur bones and imagining what the dinosaurs looked like at the very moment before the meteor hit. That doesn't make him a modern dinosaur, or a reluctant savior of dinosaurs. It makes him an archeologist.

You know what '80s rock I'm most reminded of when I listen to the War On Drugs? The Hooters' 1985 hit "And We Danced." You guys remember the Hooters? It's OK. No one does. Anyway, "And We Danced" sounds like what you'd get in some utopian alternate timeline if you asked Max Martin to write and produce "Born To Run" for the Cars. I'm not saying it's a perfect 1:1 comparison, but if you listen to "And We Danced" (below) back-to-back with "Holding On" (somewhere above) I think you'll get what I'm saying.

"And We Danced" is 100% perfect and yet shockingly wrong and immediately, absolutely, better than you dreamed it would be when you imagined it in the first place. There's a total agnosticism to the arrangement: It opens with a mandolin where you'd expect a piano; every time you're waiting to get hit with a guitar, you get a synth instead. Every time you do get hit with a guitar, another synth joyfully drops in and bumps it aside. The hooks just smack you silly. The lyrics are basically nonsense but they seem to recognize all the appropriate signifiers. Every once in a while, you'll get a big "WOO!" Just like Bruce would do it. Or what a Martian would do if he were trying to pass for an Earthling by imitating Bruce.

"WOO!"

I'm gonna bring up two things now, one fun thing, one not fun thing.

Fun thing: As you're probably aware if you read, like, The Daily Mail or whatever, Adam Granduciel is in a relationship with the actress Krysten Ritter. They've been together since August 2014. They seem like a cool couple. It brings me some small joy to know they found each other and have stuck together through these no-doubt chaotic years in their respective lives.

The reason I care at all, though, is because Krysten Ritter is one of my favorite actresses, totally independent of her relationship with Granduciel. I know, everybody likes her after Jessica Jones, and everybody remembers her in Breaking Bad, but I'm the only person here who's marathoned the entire too-brief run of Don't Trust The B... In Apt 23 -- including the unaired episodes, all in their intended sequence -- three times. That show is fantastic and it deserved a whole lot more time than it got. Seriously. James Van Der Beek is a revelation. It's on Netflix, you gotta watch it.

MY POINT, though, is this: I paid unusually careful attention to the lyrics on A Deeper Understanding, just because I was trying to see if I could identify Ritter somewhere among them. And I couldn't. To the extent I could even identify actual words among Granduciel's vocals, I couldn't find any string of words that seemed to reference Ritter. (Which, honestly, came as a huge relief. It really would have driven home all the "savior of rock" shit if Granduciel had penned his own "Rosanna.")

It wasn't just Ritter, though, that seemed absent. I couldn't find anything in Granduciel's lyrics. I'm not saying there's nothing in there, but I have now listened to A Deeper Understanding MANY times, and I can't discern any intended meaning or message in its lyrics. They're vague and opaque. He repeats and emphasizes certain words throughout the album, suggesting they have thematic significance, but these are words like "pain" and "dark" and "love." Not, like, "Rosebud" or "Ybor City." They don't even have a clear tone. Wizened? Wistful? Mournful? Suicidal? I dunno.

At some point, I decided that was the intended meaning. I chose to experience the lyrics as if they were buckets: If you look in the bucket and you find something in there, then you found what you were supposed to find, and that's yours to keep. If you look in the bucket and it's empty, then it is yours to fill with whatever you need it to hold, whatever fits, and once you've filled the bucket, the music will carry all that stuff just for you.

Moving on...

Not fun thing: I'm not here violently rejecting the "old-time rock 'n' roll" narrative because I'm some Dewey Decimal obsessive who spins out at the slightest taxonomical imperfection. (I mean, I AM precisely that thing, but that's irrelevant in this particular case.)

I'm tweaked by this because every time I hear somebody saying that this 38-year-old blue-collar white-Jesus dude has emerged from down in the valley or Allentown to save rock music, I don't hear praise, and I definitely don't hear appreciation. I hear subtext. I hear a fucking dog whistle. And I don't think anybody intends to be blowing that note, but right now, to me, it's unmistakable. It makes me want to vomit. That's not what I hear in A Deeper Understanding. I hear openness, I hear art. I don't hear a rallying cry for cultural heritage. It's not there.

I read this interview Granduciel did when he was finishing up A Deeper Understanding, and he talked about what it sounded like. This is what he said:

This new album is darker than the last one. It has a real sickness sound.

I know what he means when he says “a sickness sound.” I think I know what he means, anyway. I know what I hear when I hear that.

Which brings me back to the buckets. There's a lyric in "Holding On" that goes like this:

When we talk about the past/ What are we talking of?

Here's what I put into that bucket, what I need it to hold: Whatever the fuck people are trying to get back -- America, rock 'n' roll, some combination of the two, something else that they don't wanna call by its real name -- is not whatever they think it is, and not something that should or could come back. It was worse than you remember. You may think you want your MTV, but you don't. And anyway, it's gone. It's dead, and if you could ask all the dearly departed what they think, they'd tell you to move forward.

In that sense, maybe Granduciel isn't an archeologist; maybe he's a medium, summoning spirits, trying to communicate something from beyond the grave. The Ghost Of Christmas Past. The Ghost Of Christmas Future. The Ghost Of Christmas Right Fucking Now.

Actually, if Granduciel were a medium, it might help to explain the filmy, amorphous quality of his songs, the way they slide through your fingers like water, the way they dissipate like cigarette smoke. It would also help to explain his lyrics on the whole: When I’m not closely studying them for references to Krysten Ritter, then I don’t even catch them at all. I can sometimes kinda hear a couple stray words, whether they arrive in a mumble or a howl, but I can never hold on to them. They never quite achieve coherence or clarity.

In fact, this is how you can most plainly identify the War On Drugs as an entirely different thing than all the reference points in the War On Drugs' music and/or the critical assessments of the War On Drugs' music. Let's try something. Read to yourself -- aloud, if you like -- this ancient couplet:

Out on the road today, I saw a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac/ A little voice inside my head said, "Don't look back, you can never look back"

I don't care if you haven't heard that song in five years. You know that lyric. You can sing it right now and nail both the melody and the cadence like it was "Mary Had A Little Lamb." That's what "rock" was like. That's "a single."

Now I'm gonna tell you something. I've listened to "Red Eyes" -- the lead single off Lost In The Dream -- about 4,000 times in the last three years. It's one of my favorite songs, full stop. I never get sick of it. But this morning, I tried to remember some of its lyrics -- verse, chorus, whatever -- and I couldn't come up with anything. Nada. Then I actually listened to the song, and even as it was playing, I still couldn't remember. I couldn't remember a single word.

Well, that's not true. I remember one word.

"WOO!"

Maybe you see that as a backhanded compliment or even an outright insult, a criticism that these songs are somehow not memorable. But if you know the songs, you know that’s not true. Frankly, that’s maybe why I love the War On Drugs' music as much as I do. Because every time I listen to these songs, they sound familiar, but they're not embedded in my consciousness like a steel fucking spike. They’re not “BAAAHHHHN IN THE USAAA/ AH WAS/ BAHHHNNN…”

These songs aren't like that. They're like recurring dreams. I know what’s going to happen, and yet, I have no idea what’s going to happen. Every time, they sound new.

This is the other way you can most plainly identify the War On Drugs' music as not "rock," but a hypnotic hologram-like simulacrum of "rock" as produced by a vastly evolved alien species. You can go to any town in America tonight and find a local bar hosting a local band, and if you request "Dancing In The Dark," that band will be able to play it for you on the spot. And if you asked them to play "Poor Places," they could do that, too. Maybe they'd have to learn the chords and lyrics, and they'd definitely have to drop all the stuff Jay Bennett brought to the song to make it the song, but they could do something that would be recognizable.

They could only do that, though, because Tweedy's parts came first. Bennett added all that other stuff in the studio. That bar band's cover of "Poor Places" would be a sad little shadow of the version you hear on Yankee Hotel Foxtrot -- it would probably make you wonder why the fuck people liked Yankee Hotel Foxtrot in the first place, why critics were ever calling Wilco "the American Radiohead" -- but it would be something.

Ask that band to do "Up All Night," though, and they would be fucked. They wouldn't know where to start. They could hole up for a month to work on it and still whatever they came out with would be wrong. They couldn't strip it down. They could maybe take it apart, but they couldn't put it back together. There's no one essential element buried underneath all the surface elements. They'd find themselves facing the same dilemma if they tried to cover just about any War On Drugs song. Maybe they could figure out a way into "Red Eyes," but where would they go with it? You might as well ask them to cover John Coltrane's immortal 1961 free-jazz interpretation of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Great American Songbook standard "My Favorite Things." They'd be lost. It would be a mess.

That's what Granduciel writes. That's the song. "The song" and "the sounds you hear when you listen to the song" are the same thing. Taiji. That's how he writes them: Granduciel doesn't draw a distinction between "folk ditty" and "sonic landscape." I'm not making this up. Prior to the release of Lost In The Dream, Stereogum did a huge feature on the War On Drugs, and in reporting that feature, Ryan Leas spent a lot of time with Granduciel. Here's a tidbit from that piece regarding the artist's process:

Though he's most often thought of as a guitar player, Granduciel usually starts composing at the piano. Sometimes he'll begin with an ambient texture and work melodies into it rather than on top of it.

Can you imagine if Jay Bennett created all that egg-beater guitar noise, handed the tapes to Jeff Tweedy, and said, "Can you work some melodies into this?" That's how Granduciel makes music! And when he's done, the songs come out sounding like fucking lost echoes of radio-rock staples! That shouldn't even be possible! Who the fuck else does that? Kevin Shields? OK, yeah, I'll give you that one. Who else? Brian Wilson? It is not a long list!

Look, I gotta get out of here or I'm gonna start frothing at the mouth, but before I do, I want to mention one other thing. While reporting that 2014 feature, Ryan also went into the studio with Granduciel and engineer Jonathan Low while they were putting the finishing touches on the War On Drugs' cover of the Grateful Dead's "Touch Of Grey." Read this:

As Low isolates and quiets tracks, the different elements of what had seemed a relatively straightforward reading of "Touch Of Grey" reveal themselves. There's one guitar solo that, when isolated, sounds nothing at all like "Touch Of Grey." It's heavily processed, a slow, sad, strange, and sort of formless thing. Think of it as the lead part if there was a such thing as a shoegaze power ballad. When the synth tracks get singled out they sound like their own standalone ambient songs... At one point Low mutes almost everything and starts tweaking a percussion tone, which results in an off-kilter drum machine sound and distant synth echoes, like the soundboard's haunted and gurgling.

Now remember, this is just how the War On Drugs produce a cover of an incredibly basic song, a song that every bar band in America knows by heart: verse-chorus-verse; vocals high in the mix carrying the melody all the way through.

That's not how Granduciel writes songs, though, and it's certainly not what you're hearing when you're listening to his songs. You might think you hear "a single" on A Deeper Understanding, but it's not there. Listen close. Your ear might identify a melody, and you might assume that melody is "the song," but if you follow that melody, you'll realize it doesn't track. It's coming from all over the place, carried by different instruments at different moments. You hear it now? Taiji. Listen! Half the time, you'll realize the melody you thought was there wasn't even there. Or it wasn't where you thought it was. You remembered it wrong. That's fine. Don't look back. You can never look back. Listen now. It's hard to put these songs into focus because they're designed to deteriorate; they begin life in a stage of deterioration, they are fading even as they emerge into view. They feel as though they are in progress before they begin, and they continue even after they've concluded. Listen closer. Don't let your mind get ahead of the music. Pay equal and undivided attention to each sound you're hearing as you're hearing it, because each sound you're hearing is equally vital to the song. Each sound you're hearing is the song. That's the song. Hear it? Listen again.

//

A Deeper Understanding is out 8/25 on Atlantic.