Over the years, the Beach Boys have often been reduced to one thing or another. Yes, they gave the world one of the seminal, defining albums of the ‘60s (and of pop music as a whole) when they released Pet Sounds in 1966. And there are great, comparatively overlooked albums in their catalog aside from Pet Sounds, like 1967’sWild Honey. Yet over the decades, it’s still been easy to write the Beach Boys off, to remember them as a relic of their era, all chirpy, super-sweet pop songs about surfing and girls. A boy band, with occasional flare-ups of artistic genius beyond their plainly evident ability to churn out well-crafted pop songs. Even in the 21st century, after Brian Wilson became a major reference point for a rising generation of indie musicians and the Beach Boys were reclaimed as an influential touchstone, they still remain somewhat to the side of the main classic rock/pop narrative, still not mentioned in the same breath or in the same way as other ‘60s legends.

The famous summertime pop band that also released Pet Sounds. That’s what it often boils down to, with the sustained innocence of their earliest iterations and the later schlock of “Kokomo” overshadowing a story that’s a lot more complex. There were years of infighting and interpersonal strife, eventually leading us to the point where that asshole Mike Love tours with a propped up, nostalgia-driven echo of the band, making sure to accept an offer to play at the Trump White House’s 4th of July party along the way. (Love has known Trump for years.) There is, obviously, Brian Wilson’s battles with mental illness. And, in a broader sense, there is the complicated story of the Wilson brothers and their upbringing overall. Which brings us to Dennis Wilson, the other lost, tragic figure in the story of the Beach Boys.

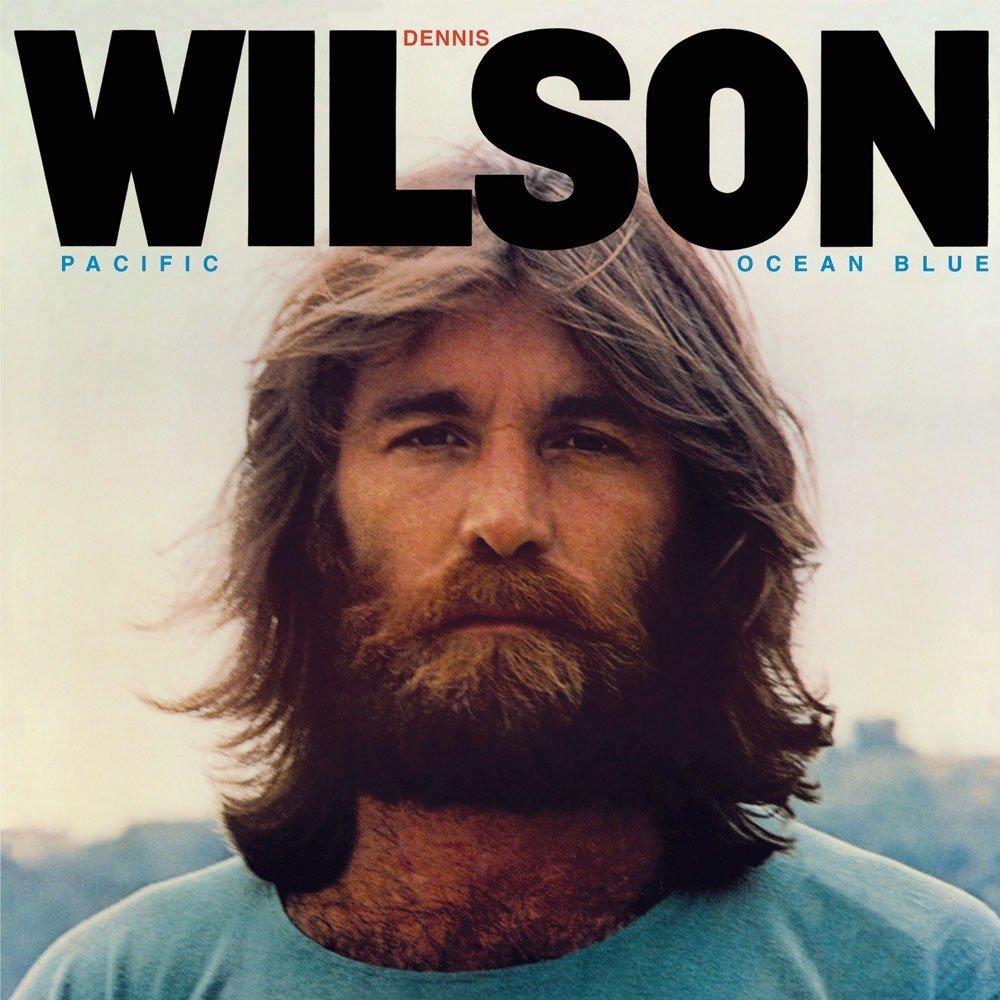

Dennis Wilson wasn’t even supposed to be in the band. Brian made room for him at the behest of their mother, giving him the not-exactly-coveted role of being the drummer (and then often having session drummers record instead of him anyway). He’s credited with the pivotal idea that the Beach Boys should sing about surfing—he was the guy in the group who actually surfed—but otherwise wasn’t considered much of an actual musician next to his genius brother, despite the fact that he did start to contribute more writing to the Beach Boys as the years went on. Even so, Love controlled the Beach Boys at that point and Wilson was sidelined. So, eventually, he became the first Beach Boy to release a solo album, in August of 1977. It was a masterpiece called Pacific Ocean Blue.

The context surrounding Pacific Ocean Blue is full of darkness. Like his elder brother, Dennis Wilson was a tortured character. He was the partier of the group, the one who lived the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. He was a charmer who was also prone to fits of rage. There was the episode in the ‘60s where Wilson was buddies with Charles Manson before he realized something wasn’t right, going as far as trying to help Manson get a record deal. The partying turned to ravaging alcoholism eventually. Wilson died by drowning in 1983, when he was just 39. He had been working on a follow-up to Pacific Ocean Blue, set to be titled Bambu, in the span of those six years. It remained unfinished when he died, making Pacific Ocean Blue the only solo record to his name.

When Pacific Ocean Blue came out in ’77, it was met with critical praise but only modest commercial success. Then, over time, it became something of a lost cult classic. It was out of print for years and Wilson was dead: Between those factors, it seemed a piece of ephemera left decades behind. Upon its reissue in 2008, its stature rose to some extent. But, like the Beach Boys themselves, Pacific Ocean Blue still feels outside of the main narratives we remember and apply to its era.

Part of the reason Pacific Ocean Blue may not feel as if it belongs anywhere is the fact that it sounds almost completely removed from the legacy of the Beach Boys. That darkness that ran through Wilson’s life? That’s woven into the album. He’s only 33 on the cover, but looks like a weathered, middle-aged man. His voice sounds nothing like the clean harmonies of the Beach Boys, but is rather a ragged, soulful growl or rasp through much of the record. Musically, you could sort of link it to ‘70s singer-songwriters or ‘70s soft rock, but the whole thing has a lived-in, dusty quality that feels like an idiosyncratic interpretation of rock tropes—revisiting it this time around, it struck me as a potential antecedent for Jim O’Rourke’s great 2015 release Simple Songs, and it isn’t a stretch to imagine My Morning Jacket covering highlights like “Dreamer” or “Rainbows.”

Despite its brisk 37-minute running time, the album plays like a sprawling late-‘70s classic. Across 12 tracks, Wilson shifted moods and styles constantly. There are melancholic ballads throughout, like the elegiac “Farewell My Friend” or “End Of The Show.” There’s the sun-fried funk of “Dreamer” and “Pacific Ocean Blues” and the simple, yearning beauty of “Rainbows,” which functions as a moment of resolution and brightness after an album that’s more often steeped in sadness. There’s the stunning opener, “River Song,” a track that has what should be too many sections and ideas for three minutes and 44 seconds, and yet pulls it off, coming together into a compact saga that feels gigantic, stacked with memorable melodies and driven by a dramatic ebb and flow.

That’s something that characterizes Pacific Ocean Blue as a whole: These are songs that often take surprising turns, seemingly straightforward initially or on the surface but veering into a new melodic idea suddenly, like the way the airy “Time” ruptures into a maddened conclusion of percussive horns and piano or how the world-weary sound of “Moonshine” changes gears for one of the only Beach Boys-esque moments on the album, an outro of harmonies that works like a salve amidst the album’s moodier tones. Almost every song feels bigger than its running time, which altogether makes for an album that feels like an epic despite (or perhaps because of) its tight editing.

Here’s the funny thing about the album: It’s actually reminiscent of the Beach Boys mythos, in its weird way. Written by the guy who actually lived a (wild) version of the life the band depicted, it’s naturally an album that feels influenced by life on the coast, life on the water. Whether in “River Song”—where Wilson sings, “It breaks my heart/ To see the city”—or on “Pacific Ocean Blues,” there’s an ecological bent to plenty of his songs and lyrics. But like everything about him as a figure and about the album, there’s a more haunted undertone, hearing his paeans to this life with the knowledge that it would eventually be the sea that would take him away.

Similarly, Pacific Ocean Blue is totally a summer album, just in a completely different way than the Beach Boys made summer music. It’s far from the fun, easygoing image of kids and cars at the beach. It’s like a broken-down, beleaguered sound for lonely, depressive times under a glaring sun. “Dreamer” heaves forward, groaning into existence as if taking a cruise on a day of suffocating humidity. All of Pacific Ocean Blue’s ballads could soundtrack solitary, drunk walks home in the middle of a summer night. In fact, that’s a quality that runs through almost the entire album—as if you could picture Wilson alone and inebriated on the beach remembering things once romanticized, a seasickness flowing through those strange left turns so many of the songs take. In that way, it’s almost like an answer to the Beach Boys mythos, or at least for the way Wilson lived it himself. If you draw a line from early Beach Boys to 1977, Pacific Ocean Blue is the sound of those childhood dreams damaged, fractured, coming apart at the seams.

Maybe it didn’t sound quite that severe in 1977. Pacific Ocean Blue, worn as it feels, is also a strikingly well-written and consistently pretty album. The hindsight, knowing that Wilson would spend six long years struggling to finish another album while battling his alcoholism and then would die at far too young an age, colors the experience of the album. It makes the elegiac parts that much more elegiac; the melancholic parts feel like foreshadowing.

Outside of the man’s personal life, there’s a sad “What could have been” element, too. The music that was meant for Bambu is often equally stunning, whether in the frayed infectiousness of “School Girl,” the swelling refrain of “Love Remember Me,” or the lite-funk yacht-rock of “Constant Companion” and imagining Wilson as the vagabond hijacking said yacht. There’s also “Wild Situation,” a song that exemplified everything Wilson did well: a rootsy, searching melody anchored by little harmonica coughs and a subtle, Stones-esque guitar groove that both forces you to move and sounds like it’s in the process of falling apart at the same time it’s coming alive.

While Pacific Ocean Blue now stands as a curious outlier in Beach Boys history and a one-off for its author, all of these depleted qualities actually do make it belong somewhere. The graveled sound of it, the strung-out character of it, the fact that it unfolds like one last, desperate gasp—all of these distinctions make it a perfect document of the late ‘70s, of the ‘60s greats and the promise of their decade running to ground. It’s the sound of the long hangover, of excess and its tolls exhaled into a disenchanted atmosphere. It came out the same year as Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, but it has more in common with their 1979 release Tusk in that way. These are the big, blown-out end games of stories that began 10 or 15 years before, the idealistic dream of the counterculture giving way to all of the sex and drugs and subsequent comedown.

It comes from a place that’s very far away from the stories the Beach Boys told in their earliest days, but it’s also the thematic extension, the real conclusion. It comes from a place that’s well beyond the loss of innocence, trying to parse everything that came after. It’s steeped in elegy—for Wilson himself, for the fabricated Golden Coast dream of the Beach Boys, for their era and generation—and that could relegate it to its time and place, a piece of cult-status ephemera like it once was. But it doesn’t. Pacific Ocean Blue is more than that. It was a flare-up of artistic genius, a work that’s rugged and heartbreaking in equal measure, a work that is still evocative and overwhelming four decades later.