Molly Rankin and Alec O'Hanley -- the songwriting duo at the core of Toronto-based indie-pop band Alvvays -- look a bit drained as they both lean on the edge of a picnic table in Chicago's Grant Park. It's hard to blame them, given that it's the final day of a sprawling four-day Lollapalooza. I'm drained too, and I didn't play multiple gigs while in town, nor am I in the throes of both touring and the awakening machinery of a new album rollout. In the next few weeks, the two of them -- along with their bandmates, keyboardist Kerri MacLellan and bassist Brian Murphy -- will bounce from city to city, preparing to introduce the world to their sophomore album. It's called Antisocialites, and it's the record positioned to move Alvvays past the blog hype that bubbled up around them years ago, past the threat of what happens when that bubble bursts.

Contrary to the name of their new album and all of our circumstances being less than ideal for deep conversation -- a daytime mainstage act rambles through a Chester Bennington tribute, blaring in the background as we talk -- the two of them are affable, always quick to detour into dry wit or a hint of sardonic self-deprecation when discussing Antisocialites. (If you're a young rock band touring incessantly in the 2010s, a dose of sardonic self-deprecation is a healthy coping mechanism.)

Having garnered indie-world buzz before ever recording an album, Alvvays released their first LP in 2014 and made good on early promises. A collection of jangly indie-pop tracks adorned with a gentle cloud of fuzz, it was able to straddle two worlds, woozy and dreamy half the time but anchored by melodies that wormed their way into your head and refused to leave. The calling card was "Archie, Marry Me," a track that took on a modest life of its own without the sort of TV-spot licensing that often boosts a young band's signature song, popping up on end-of-year lists and earning a shoutout and cover from Death Cab For Cutie's Ben Gibbard. Alvvays then toured a ton behind that album, before returning three years later with the first previews of Antisocialites: lead singles "In Undertow" and "Dreams Tonite."

Those two songs are not a feint. Across Antisocialites, the latent dreampop elements in Alvvays' music get heightened a bit (perhaps thanks to a recent obsessive streak with Cocteau Twins' Heaven Or Las Vegas). The bones are still the same -- these are punchy, catchy songs -- but there's a light nocturnal sheen across it. It's often more shimmery and glossier than the band's first record, sounding like the bleed of blue tones and blurred lights on solo walks through the city at who knows what hour.

That may or may not be exactly where Antisocialities was conjured up, but it definitely isn't far off. "It feels like a bit of a separation record," Rankin explains. "[I was] plotting out these vicarious narratives of going on solo journeys, whether that be on a ship or driving across the country by myself. I was just envisioning these cinematic narratives."

"I think the divergent tactics in the record are kinda like, 'OK, how do I get out of Dodge,'" O'Hanley adds. "You'll try anything to get to a better spot."

Rankin's quick to underline it with a joke -- Alvvays spent so much time on the road together that Rankin found herself fantasizing about "having a significant amount of time by myself." But that's only partially a joke, and there's a real way in which "a certain despondence" was fundamental to the album, too. When they finally got home to Toronto, Rankin felt the need to "recharge," that the band members should all retreat to their respective corners and lives for a moment while she spent some time finding inspiration once more.

Despite a connective tissue of emotional detachment running through all the songs on Antisocialites, Rankin asserts that the album comes together as a collection of vignettes more so than a Point-A-to-Point-B-type narrative arc. Yet while these stories might be discrete, O'Hanley also hears a consistent voice throughout. "It's a constant narrator, in a sense," he begins. "You can't always trust the narrator in the songs. Sometimes the narrator gets drunk."

The transience of being a touring musician, of living life on the road and passing in and out of city after city and countless people's lives, is an underlying influence for all of it: the way the songs feel like they offer you a glimpse before blowing away back out of reach, that despondence, the sense of Antisocialites as a loose collection of moments and locales, even the way Rankin's perspective is both present and fictionalized throughout, like she's passing in and out of her own life. "I think all the feelings are very connected to me," she says of her writing process. "I do like to escape into other possibilities that I don't necessarily experience, situations that I couldn't possible find myself in. Some of it, I draw from personal experience."

A transient life is also a good way to avoid, or not be able to find, conclusive endings to things, and that's true of Antisocialites as well. While O'Hanley describes moments of "attempted redemption" cropping up throughout the album, there's no clean, linear progression for the band or the narrator. It's little moments of clarity scattered along the path. He and Rankin joke back and forth for a moment about whether Alvvays could be qualified as "Hopeful pessimists" or "Skeptical optimists." "We're rarely cut and dry," O'Hanley offers. "We try to reflect life, in that way. Fairytales aren't in vogue these days."

"The record ends with living in the moment," Rankin says, offering up the closest approximation of a resolution you'll find on Antisocialites. "Things may not be perfect, but here we are, regardless."

A few days later, I cross paths with Alvvays again in New York. We meet up in this weirdly greenhouse-esque patio area in the back of the Bowery Hotel's lobby, both Rankin and O'Hanley leaning forward from a couch, digging back into the history of Alvvays, everything that preceded Antisocialites and how it got them here.

When you ask Alvvays about the (at least, perceived) amount of buzz surrounding their introduction and first album, they're somewhat skeptical. Inside, it didn't feel quite that way. "It seemed reluctantly revered," Rankin recalls. "People were like, 'I hate to say it, but I like this.' That should be our tagline on whatever [social media] platform."

"[It was] begrudging approval," O'Hanley says. "We haven't seen the hushed, reverent tones that some other people inspire."

"I think it's symptomatic of guitar music," Rankin adds.

Yet while the proscribed narrative of "nobodies to buzz band overnight" doesn't resonate with either of them, there have been surreal moments along the way. O'Hanley cites the moment where their debut hit #1 on US college radio. And both of them speak fondly of "Archie, Marry Me," a piece of writing where they were able to really connect with a lot of people. "When a song like that, which is near and dear to us, does enter some people's conscsiousnesses, we do breathe a sigh of relief," O'Hanley says. "When that is confirmed by other people, we're kind of over the moon internally...for at least 10 minutes."

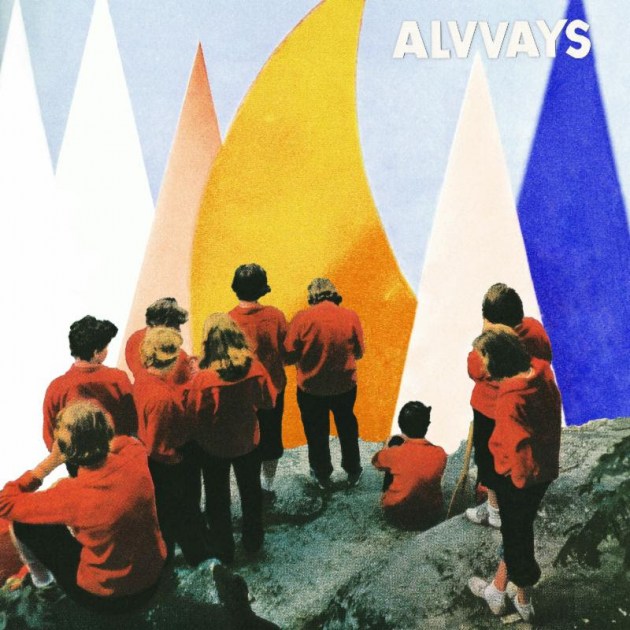

That qualifier is something that's ever-present in conversation with Rankin and O'Hanley. At another point, Rankin quips that the success they found in their sphere wasn't always that noticeable since those moments where they were told "yes" were heavily outweighed by moments of being told "no." And though they seem to chafe at the term "DIY," there is the basic fact that Alvvays are one of those bands that still handles a lot of its own shit, whether it's working the merch table after a show or designing their own album art. (The excellent dreamscape Pop Art cover of Antisocialites, for example, came from collages of old periodicals that O'Hanley and Rankin found upon "cheating" their way into the University Of Toronto library. "We did that more times than I'd like to discuss," Rankin deadpans.)

Rankin and O'Hanley's tendencies toward a blunt matter-of-fact attitude or that self-deprecation could also be tied to their roots. In recent years, there's been an upswell of new rock bands coming out of the Toronto scene, and Alvvays could be lumped into that, on the surface. Yet the individual members grew up in more bucolic surroundings, up and over in the Maritimes.

For Rankin, that meant growing up immersed in Celtic music and culture. In school, she had a choice between learning French and Gaelic. One of the pillars of Alvvays' origin story is the fact that Rankin first experienced the life of a touring musician via playing with the her family's Celtic folk outfit, the Rankin Family. In the meantime, O'Hanley experienced more of a traditional rock scene over on Prince Edward Island. When Rankin was around 20, she found her way there, too, and began playing her own music at open mics. It was folkier, before she and O'Hanley started working with their friends and began to develop a more rock-oriented sound.

The move to Toronto was more practical than anything. "It's tough to do it from an outpost," O'Hanley explains. "It's no slight to the place, it's just sheer geographic limitation. You wind up living in transit, on the road to Toronto." (Rankin also recounts stories of saving up waitressing money to make the 16- or 17-hour trek down to Toronto to play a 20-minute set.) They both speak highly of their time there, with O'Hanley remarking that it "nurtured" them as people and musicians.

The other lingering effect is that they don't exactly feel a part of the Toronto scene or its narrative. "We're not a large part of the scene in Toronto," Rankin says. "We're a little bit of a transplant band."

"As a Maritimer, you're pretty clannish just by default," O'Hanley says, explaining that a lot of Alvvays' circle in Toronto are people like them, who came from farther-flung provinces. "It's not a snobby thing, it's just that you have a shared history."

That's not where their attitude comes from, though, the idea of the rural kids moving to the city and sticking together. It's really just the fact that, well, not a lot of well-known bands exactly came out of the towns Rankin or O'Hanley or their bandmates grew up in. You don't necessarily expect anything to happen, so Alvvays never had their eyes set on world domination. As O'Hanley jokes: "It's the land of tempered expectations. And potatoes."

"If something happens, great," Rankin says, explaining their outlook going into the band. "If nothing happens, fine."

"The land of tempered expectations," after all, could also simply describe the existence of a rock band in 2017, or the existence of an indie band that has the benefit and burden of that semi-artificial out-sizing that can be a consequence of online buzz earlier on. For a band in Alvvays' position, it would've been easy to take all of that and tour themselves into the ground, to keep going for fear that it could evaporate if, say, they took three years from debut to sophomore album. For that matter, there could be the threatening specter of the sophomore slump. They claim that, while making Antisocialites, they tuned all of that out.

"We were happy with what our first record did. We were trying desperately not to succumb to 'The Next Step,'" O'Hanley says. "We're pretty content with who we are, our life. I think on this record, we just tried to write good songs and document them accordingly."

Whatever happens, happens. That could easily be the takeway from a conversation with Alvvays, and it's not entirely untrue -- again, a hybrid of realism and self-deprecation appears baked into their DNA. But there's a reason they moved to Toronto. A reason they gravitated towards pop forms beyond their attention to craft.

"We're a pop band," O'Hanley asserts. "The goal was for people to hear our music. We don't want to stash our songs in the basement and just leave them down there."

Antisocialites is out 9/8 via Polyvinyl. Pre-order it here.