It finally happened. The National finally made a rock album. I honestly thought it would never happen again. Back on 2005's Alligator, when many of us first met the National, they were still a rock band. That version of the National wasn't too terribly different from the one that evolved out of it; back then, they were still interested in layered arrangements and dour vulnerability and quietly dramatic melodic swoops. But they also came up with big, nasty, cathartic choruses. Some of their songs sounded like anthems, and when they performed those songs live, they took on a messianic intensity that they quickly discarded on later records. When I interviewed frontman Matt Berninger a few years after Alligator came out, he used the phrase "screaming my head off" to describe how he'd sung on "Mr. November" and "Abel," and he didn't seem eager to do it again.

Instead, the band found a more sedate sound, a musical equivalent of extremely well-made dark-wooden furniture. Their music became a dark, sophisticated swirl -- red-wine music, music that people would put on at dinner parties when they wanted to seem cool. Members of the band helped spearhead Dark Was The Night, which collected and codified indie rock's new respectable, genteel vanguard, and the Day Of The Dead compilation, which asserted that the Grateful Dead were indie's new bellwethers. They showed up on virtually every prestige TV show. They became a sort of NPR institution. None of this was bad necessarily, and the National made a lot of incredible music -- those slow-building, slow-burning monolith-jams -- during that era. They also became extremely popular: popular enough to play arenas on their own. So it's a shock to put on Sleep Well Beast, the band's seventh album and first in more than four years, and realize that it rocks.

You will still be able to play Sleep Well Beast at dinner parties, but the dinner parties might get a little stormier than they once were. The new album does a better job than any past National album at integrating the experimental-music passions that the two Dessner brothers, Bryce in particular, have been chasing during their personal time over the past decade. You can hear that in the way the processed guitars on "The System Only Dreams In Total Darkness" impersonate car alarms, or in the way drums and synths skitter and pulse all over the title track. Even more than their last few albums, it's an intricately arranged affair; you can hear layer after layer of strings and keyboards and guitars on every song. But instead of derailing the songs, those experimental touches have made the songs bigger and grander. And they've also jacked up the urgency.

There are peaks and valleys all through Sleep Well Beast, and plenty of the songs are as thick with quiet atmosphere as any previous National songs. But for my money, the best songs on the album are the ones where Berninger comes closest to screaming his head off. "Turtleneck" is desperate and wounded, a crumbling and teetering wall of sound with a guitar solo that sounds like a dial-up modem. "Day I Die" has drums that, if properly harnessed, could power an entire office park. (This is a good place to point out that Bryan Devendorf is one of the three or four best drummers in indie rock and that the National would become incalculably shittier if he ever decided to hang up his sticks.) "I'll Still Destroy You" sounds like end-credits music for a movie about a couple who repair their relationship while barricading their doors and windows to keep out the horde of vampires who are trying to get in and kill them; it's what plays when the two of them wander out, bloodied and battered, to see the sunrise.

So Sleep Well Beast kicks harder than any National album in more than a decade. It's also better-written. The National have never been a lyrics-first band. Instead, Berninger's burnt-umber mutterings have just been one part of the overwhelming whole. But Sleep Well Beast might be the first album in the band's career that's actually about something, that speaks to emotions that many of us know very well. Berninger has said that the album is "about marriages falling apart," and he co-write its lyrics with his wife, the writer Carin Besser. I've seen the album described as a breakup album, but it's not that. Instead, it's an album about the eternal struggle to not break up. It's about growing old with somebody, about watching yourself become a different person than the person your partner met, and about watching your partner turn into someone who you might not recognize. It's about the dangers of losing yourself in the hectic grind of working jobs and raising kids, of becoming burned-out husks who stare at your phones or your TV at night instead of talking to each other. For those of us who are, like Berninger, getting old, that's not some abstract existential dilemma; it's a real and vitally important issue.

On long stretches of Sleep Well Beast, Berninger lives in the past, remembering seeing his wife around town before talking to her, or having intense conversations in the back of Warsaw, the Greenpoint venue where I first saw the National. (He's literally flashing back on the Alligator era as his band goes back to Alligator-era levels of raw vitality.) The most drunk-on-memory song is literally called "Carin At The Liquor Store." But when Berninger focuses his attention on the present, he tends not to like what he sees: "I barely ever see you anymore / And when I do, it feels like you're only halfway there." He knows he's got the same problems: "I’m always thinking about useless things / I’m always checking out." He meditates deeply on the idea that it's all over, that there's nothing either of them can do to save it, that it's just the natural order of things: "It’s nobody’s fault, no guilty party / We just got nothing, nothing left to say." In venomously petty fashion, he mentions that he can get laid anytime he wants, bringing it up like that'll end the conversation when he should know that it'll only make things worse: "Young mothers love me / Even ghosts of girlfriends call from Cleveland / They will meet me anytime, anywhere."

Berninger has said that the act of writing those lyrics, with his wife, was what saved his marriage. So it's an exorcism, an intense public therapy session. Berninger's never done anything like that before, at least not in such plain language. And when Berninger sings about his marriage, he discovers something worth saving. Immediately after dropping that mention of those girlfriends in Cleveland, he wonders, "The day I die, the day I die, where will we be?" And later, he looks at the world around him with something approaching an elder's wisdom: "New York is older and changing its skin again / It dies every 10 years, and then it begins again / If your heart was in it, I’d stay a minute / I’m dying to be taken apart."

So: Sleep Well Beast is an album about getting old and staying together. That makes it, on some fundamental level, the most domestic album ever made by a band that's always been pretty domestic. And yet Sleep Well Beast bursts with conflict and passion and restlessness. The National's albums take time to reveal themselves, but Sleep Well Beast already feels like the best thing they've done since Boxer. The members of the band wouldn't be happy to hear it, but for about a decade there, they were making background music. They were really good at it. It was excellent background music. But now they're making something else, and now I'm hoping that the background-music National never come back.

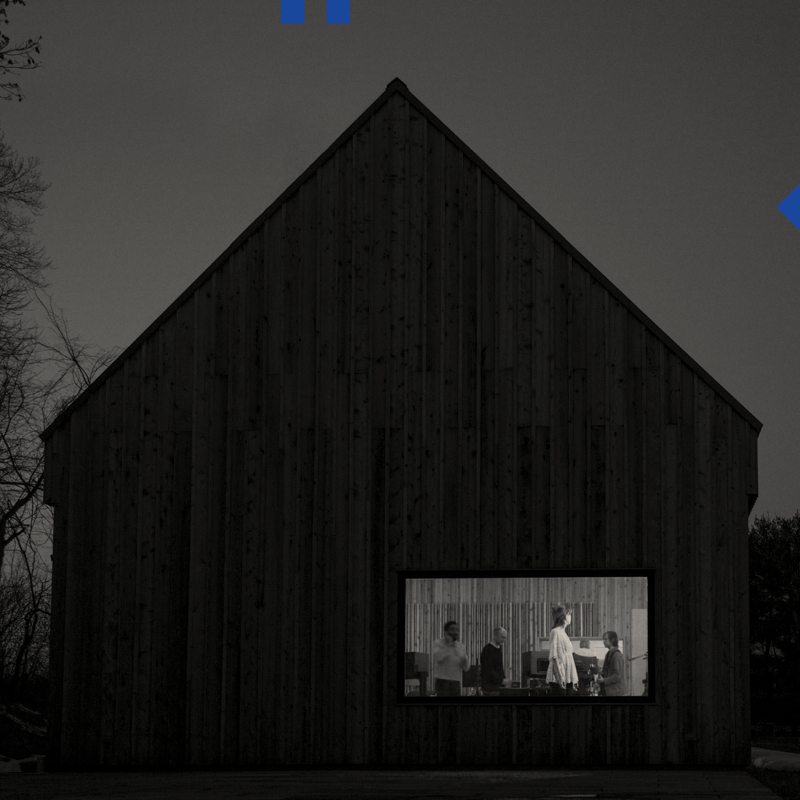

Sleep Well Beast is out 9/8 on 4AD.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]