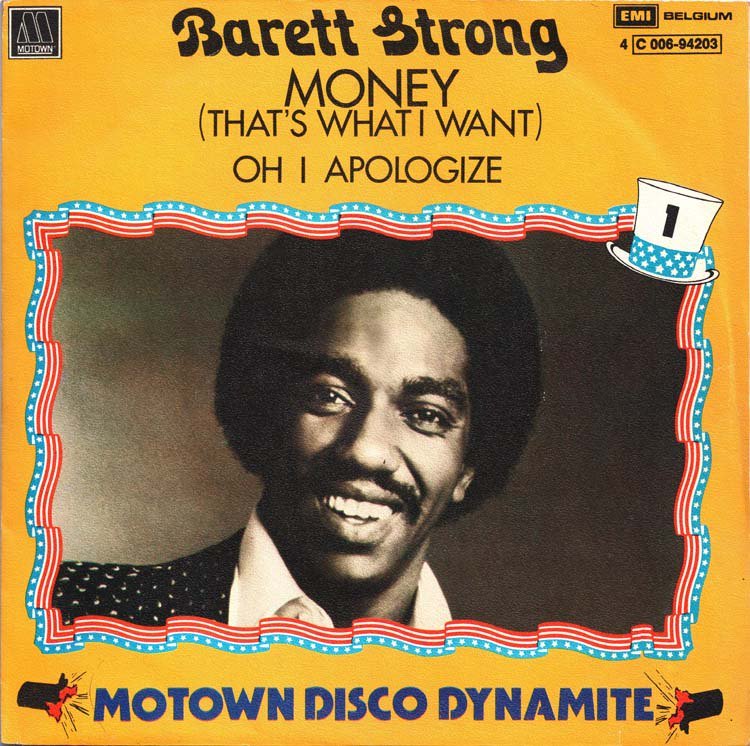

Barrett Strong only had one major success as a singer, but since (a) that major success was the first big hit for one of the postwar 20th century's biggest entertainment institutions and (b) pretty much everybody who was anybody and a fair number of mere somebodies did a good-to-great interpretation of that success, his legacy was pretty much secured even before he "settled" for co-writing a kiloton of Temptations classics with Norman Whitfield. This could've easily been the first and possibly last 20-entry Gotcha Covered -- as it turns out, a significant number of musicians since the 1959 release of "Money (That's What I Want)" found a real charge in taking on one of the most bluntly cynical pop songs to ever discuss life under capitalism. I could've thrown in versions by Don Covay, Cheap Trick, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Jr. Walker & The All Stars, Jim Belushi, the Doors, Boyz II Men, Smashing Pumpkins, and Josie & The Pussycats, and covered nearly every single possible point on the irony-to-sincerity scale. I also would have reduced myself to a stammering homunculus incapable of fiscal responsibility or an ability to assign non-monetary value to immaterial concepts such as friendship and beauty, so you get what you get.

Anyways: It's a hell of a feat, song-wise, a crushingly depressing sentiment made to sound almost triumphantly aspirational: "Your love gives me such a thrill," goes a sentiment found in dozens of thousands of pop songs up to that point. "But your love don't pay my bills." And that third verse -- "money don't get everything, it's true/ but what it don't get, I can't use" -- stood as one of the all-time don't take this line at face value philosophy to emulate, ferchrissakes lines on the subject until a generation of coked-up fratboys thought Gordon Gekko's "greed is good" deserved a hell-yeah. Here's a few versions to line your pockets.

John Lee Hooker (1960; 1966)

If you've ever considered Motown and electric blues to be at opposite ends of a pop/authenticity spectrum, here's something to knock you for a loop: John Lee Hooker, a blues icon if there ever was one, covered the song that put Tamla/Motown on the map -- twice. Call it one sound of Detroit paying homage to another: Hooker came up playing Motor City clubs while working for Ford and, among other things, wrote maybe the definitive song about the Detroit riots of 1967, so small wonder he wound up putting his own voice to "Money" -- and made it sound more like a restless, nagging itch than a giddy get-rich-quick scheme both times. The version from 1960's That's My Story is a solid acoustic take that gives his voice a lot of open space to ramble, but the best version is the full-band take from his 1966 Impulse masterpiece It Serve You Right to Suffer -- the only album Hooker released for the jazz label, produced by Bob Thiele the same year he worked the boards on John Coltrane's Ascension. He drops a rhyme-scheme-flouting paraphrase or two as a sort of punchline at the freewheeling expense of the song's then-ubiquity ("Money don't get everything it's true/ What it don't get, I don't want"), but even better is how the serrated edges of his voice, his electric guitar, the band's perpetual-motion boogie-shuffle groove, and even the guest spot from William Wells on trombone (!) sounds like it's all sawing the song to pieces.

The Beatles (1962)

The version of this song from '63, whether on 7", With The Beatles, or The Beatles' Second Album, is the version most of you probably know the best -- but then there's the Best version of it. (Sorry.) The New Year's Eve/Day 1962 sessions the Beatles cut for their Decca Records audition is infamous for a number of reasons, the most notorious being that the label subsequently rejected them because "guitar groups are on the way out." So if you ever wondered what kind of performance would cause someone at that label to drop the ball that hard, here's a piece of it, back when Pete Best was the drummer and the Cavern Club was still the main stomping grounds of the Fab Four (beta release version). You can hear the Beatles as a clambering, gnarled sort of proto-garage band here, with Best's tempo-hitching rumble and John Lennon's raw, sometimes ragged voice revealing them as the electrifying yet still shaky work-in-progress they'd drastically fine-tune over the course of the following year. The Stones did a characteristically scuzzy version in '64 (funny enough, as a flipside to the Lennon/McCartney-written "I Wanna Be Your Man"), and Lennon revisited his early years with a loping, more intrinsically ironic version recorded with an all-star band in Toronto during the height of his peace-activist Bed-In phase, but the '62 Decca session still sounds the most fascinating version to emerge from the British Invasion -- even though the invasion's plans were still being drawn up at the time.

Jerry Lee Lewis (1964)

I'm halfway tempted to just paraphrase what my guy Kaleb Horton said about Live At The Star-Club, Hamburg and leave it at that: "It's one of those albums I can’t even talk about because it's so tempting to get greedy about superlatives and look like a liar. A vicious, thundering performance where everything is too fast and the songs aren’t sung so much as roared. It makes you want to steal a car." I'm not one to argue, honestly, especially considering the time-and-place context. Much in the same way it's less important how good Wilt Chamberlain would be if he played today than it is about how he was so dominant in his own time he made all his contemporaries look like the kind of mopes who'd let someone drop 100 points on them, Jerry Lee Lewis in 1964 basically recalibrated how raucous rock could be. No matter if the Who and Jimi Hendrix pushed the bar even higher within a couple years -- Live At The Star-Club made all that feasible, as Lewis and the Nashville Teens thunderbolted their way through a revue of the previous 15 years' worth of rock 'n' roll iconography like their hair was on fire and the only way to put it out was with a volume-activated sprinkler system. The percussion absolutely knocks you over on this -- and everything is percussion here, including Lewis' voice, perched somewhere between a glower and a leer. His ad-libbed laughs are the stuff of Robert Mitchum threats.

The Sonics (1965)

Live At The Star-Club was a Europe-only release, which means that if you didn't have a good import connection most word of it had to come from secondhand lore. And if some young dirtbags in the Pacific Northwest had to reproduce it just by going off its reputation -- and then ramp it up even wilder -- well, there's a goddamned game of telephone for you. So who else would you trust to that task but the Sonics, the Tacoma band that took garage rock to its most deranged heights by asking "what if the Kingsmen actually went around beating people up with motorcycle chains" and adjusted accordingly. And if Lewis' "Money" is the soundtrack to car theft, the Sonics' version is for straight-up bank robbery. Gerry Roslie has the formidable task of hollering over the maelstrom behind him, but because everything is already loud, hey, he's gotta be louder. And since the guitarist/bassist Parypa brothers are conspiring to out-blast Rob Lind's sax and Bob Bennett's drumming is mic-ed in a way that makes your typical Ramones backbeat sound like "Why Can't We Live Together," Gerry's notion of loud has to maintain this barrel-chested urgency that ambushes you like a neurotic housecat: from a smooth confidence to a hair-raising yowl with zero warning and one million billion decibels. So yeah, money is what he wants; god help you if you're in the way when he's coming to collect it.

The Supremes (1966)

What a difference seven years of empire makes. Swap out the howling Barrett Strong for the glamorously cool Diana Ross, that galloping guitar riff for an army of horns, the youthful rawness of the original hammering-it-out band for the full-force tightness of the early-prime Funk Brothers, and money being something you want to it being something you've got. There's still that war-drumming tom tom in the back, sure, but that's the last truly recognizable instrumental vestige of the original, which has been reupholstered in velvet and now furnishes a really lavish penthouse suite. Yet in its most common context, the second side of their LP The Supremes A' Go-Go, it's almost an afterthought in a year that also gave us #1s in "You Can't Hurry Love," "You Keep Me Hangin' On," and "Love Is Here And Now You're Gone." It's a fine performance, just more fascinating as a contrast between eras: the upstart indie label turned definitive Sound of Young America.

Buddy Guy (1970)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=tu4gbiZegP0

By nearly every measure, 1970's Festival Express was a logistical and financial nightmare. As an actual touring music festival, it was hard to beat, even in the diminished atmosphere of a post-Altamont world: Janis Joplin, the Band, and the Grateful Dead anchored the top of a traveling lineup that also included appearances by the Flying Burrito Brothers and Buddy Guy. Yet despite its novel setup of ferrying the band members and crew across Canada on a train, which gave its musician passengers plenty of time and opportunity to get absolutely shitface wasted and play some wild jam sessions, the whole enterprise was practically doomed: planned stops in Montreal and Vancouver were cancelled, the show in Toronto was bumrushed by protestors angered at price-gouging admission, the Winnipeg stop had less than five thousand fans in the audience, and in Calgary show promoter Ken Walker got into a tete-a-tete with mayor Rod Sykes that apocryphally culminated in the former punching the latter in the mouth. Was it worth it? Well, we got a great documentary out of it -- eventually, a few decades after the fact, once all the lawsuits were settled -- and Buddy Guy's performance of "Money" is the show-stealer. The blues guitar god cut his own version on LP two years previous, which is fine enough, but this version is a motherfucker deluxe -- everything great about blues, soul, and hard rock all at once in a blistering five minutes. The man pulls off one of the most miraculous guitar solos on a forklift.

Mandré (1977)

It's not like songs about the nagging irritation of being broke weren't popular in the '70s -- hell, in 1973 alone "Greatest Hits-caliber blockbuster song with a killer bassline and lyrics about the perils of money" covered both Pink Floyd and the O'Jays. But in an era choked with stagflation, austerity, recessions, gas shortages, deindustrialization, and a dozen other disillusionment-fueling financial crises, "money is technically necessary in this capitalist hellscape but goddamn it's a pain in the ass" seemed like a more appropriate prevailing lyrical mood than "fuck everything that can't be bought." Wages had already slowly begun their now decades-long flatlining when Johnny "Guitar" Watson and Frank Zappa tourmate/collaborator Andre Lewis, a/k/a Mandré, made his debut for Motown. As his somewhat proto-Daft Punk-esque spaceman/robot(?) alter ego, the enigmatic metal-masked synthesizer wizard, producer, and arranger melded funk, jazz fusion, and prog to little chart response but huge cult affection, with the Stevie-via-Moroder-via-ELP freakout "Solar Flight (Opus I)" and Detroit-area Electrifying Mojo-curated boogie funk favorite "Freakin's Fine" some of his more revered cuts. And in what feels like a deliberate nod to The Future of Motown, there's a version of "Money" on Mandré's self-titled '77 debut that sounds like the kind of state-of-the-art synth-funk epic that aimed to pose a challenge to P-Funk's Afrofuturist throne. Lewis totally belts on this one, the human voice working overtime behind all the hi-tech components, and the arrangement is peak freewheeling funk at its silliest and heaviest all at once. Shouts to Penelope Periwinkle from Your Credit Corporation.

The Flying Lizards (1979)

Just how detached can you possibly sound singing this song, anyways? Art-noise collective the Flying Lizards figured that one out pretty thoroughly. Their notorious version of "Money," a curveball #5 pop hit in the UK, straddled bizarro novelty and avant-garde brilliance in a way some of the greatest post-punk did -- a minimalist deadpan that deconstructed and toyed with the way the lyrics read as sociopathology in the right (or wrong) hands. The video's part of that hilarious, sometimes unnerving push-and-pull, intercutting Get Carter-style gangland car-chase action with shots of singer Deborah Evans-Stickland looking almost as dispassionately tense as she sounded -- she doesn't so much move as she just agitates. And the instrumentation sounds like an unholy union of a Wild West saloon piano via John Cage and some of Lee "Scratch" Perry's more off-the-beaten-path dub productions, along with a guitar solo that sounds like someone took Buddy Guy's Festival Express performance and siphoned out anything below a certain threshold of sheer noise. A segment on a BBC Four documentary on cover songs, Better Than The Original, highlighted their particular approach -- producer David Cunningham pointed out that the great thing about pop covers is that recognizable pop structure allows for a lot of room for the bizarre. A lot of room. Funnier still is Evans-Stickland's reasoning as to why the Flying Lizards so often gravitated towards covers, such as similarly deconstructionist takes on Eddie Cochran's "Summertime Blues" and Curtis Mayfield's "Move On Up": "there are plenty of good ideas, why bother to have any more?"

Charli XCX (2014)

So is there even a contemporary context for this song? It's been on the edge of sincerity from day one, reconfigured with different calibers of ironic underlying meaning and circumstance over the ensuing twenty years, then largely faded as a standard around the same time Thatcher and Reagan stepped into power and presided over a world where greed became significantly less taboo. Pop culture as an oppositional force reacted with the times: in the DIY '80s and '90s, stating outright that you wanted money meant you were a sellout; in the striving like/follow/subscribe '00s and '10s, it meant that you didn't have any, which could be considered even worse. Charli XCX's path from indie-friendly millennial electro-pop post-genre star to PC Music-affiliated, market-averse iconoclast has been strewn with thinkpiece debris and expectations of pop in an age where superstardom's relegated to the 1%. So how much of a snark move was it for her to record a cover of "Money" and relegate it to the bonus track of a special edition of Sucker you can only get physically at Target? Who knows, but it sounds like if the Flying Lizards version was 500% more willing to conflate greed with horniness, which makes for an excellent jam as far as blatantly obvious statements go.