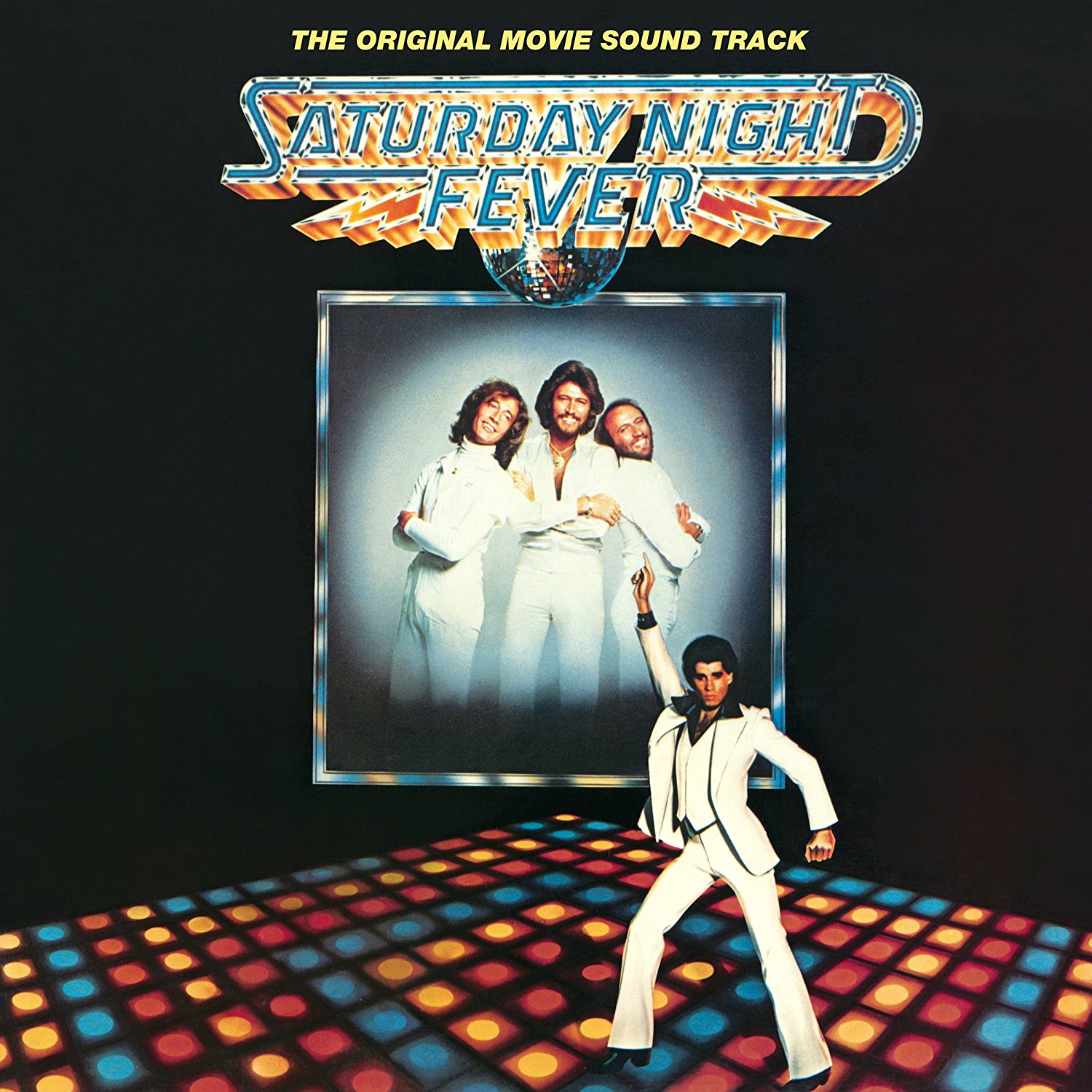

How do you reckon with a monolith? There's a monologue at the end of Whit Stillman's 1998 film The Last Days of Disco where a character in the early '80s speaks with the hindsight of a late '90s nostalgist that "Disco will never be over... Oh, for a few years -- maybe many years -- it'll be considered passé and ridiculous. It will be misrepresented and caricatured and sneered at, or -- worse -- completely ignored. People will laugh about John Travolta, Olivia Newton-John, white polyester suits and platform shoes and people going like this." And then he pulls the finger-in-the-air pose made famous by Travolta, immortalized in both the poster and on the soundtrack cover of Saturday Night Fever with an ironic disaffection. "Disco was much more, and much better, than all that," he protests -- and the grip of Saturday Night Fever was so long and powerful on the pop culture imagination that his protest still held weight 20 years after its initial first run saw it emerge as one of the biggest phenomena of the '70s.

Cutting it all apart took a while -- starting with the attempt to re-release the film in a PG cut to draw in the younger teenage crowd in '79, then on through a disco backlash, an abysmal sequel (1983's Stayin' Alive), the later disillusionment of the soundtrack-anchoring Bee Gees ("We'd like to dress 'Stayin' Alive' in a white suit and gold chains and set it on fire," Barry Gibb once scowled), and the 1996 revelation that the story that inspired it all -- Nik Cohn's "Tribal Rites Of The New Saturday Night" -- was largely fabricated by a confused Brit who couldn't make heads or tails of the New York clubgoers 10 years younger than he. Nowadays, the idea of severing a disco scene from its queer and Black/Latinx ties in favor of a story featuring a bunch of white teenage mooks would be rightly mocked.

But today -- the 40th anniversary of the soundtrack's release -- one thing's still for sure: That music is damn near immaculate. The Bee Gees cuts might not have been added in until post-production -- Travolta claimed to have done most of his dancing to Stevie Wonder and Boz Scaggs -- but that Disc 1 Side 1 run from "Stayin' Alive" through "More Than A Woman" is bulletproof, and Yvonne Elliman's version of the Gibb/Gibb/Gibb track "If I Can't Have You" is debatably even greater. The classic cuts that round the OST out, from earlier Bee Gees jams like "Jive Talkin'" and "You Should Be Dancing" to circa-'76 cuts like KC & The Sunshine Band's "Boogie Shoes" and the Trammps' "Disco Inferno," forego the new-hotness glamor of Studio 54 or the genius curatorial idiosyncrasy of a Larry Levan Paradise Garage set for the vibe of a second-rate Brooklyn disco that feels a few months behind the times -- good thing those months sound great after decades. As for the wider music world's attempts to put their own stamp on the omnipresent soundtrack? It almost seems to parallel the rise, fall, and afterlife of disco itself, from its prehistory to its sublimation into latter-day dance music. Here's the legacy of Saturday Night Fever in eight of its more fascinating cover versions.

Rufus & Chaka Khan - "Jive Talkin'" (1975)

Funny how the greatest cover of any of the songs from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack is for a track that was cut from the movie and actually predates the film itself by some two years, but here we are: Give Chaka Khan a song someone else recorded, and she claims ownership like few singers out there. After pulling that feat off on three consecutive LPs -- reshaping every transcendent note in Stephen Stills' "Love The One You're With" for Rufus' self-titled '73 debut, Ashford & Simpson's "Ain't Nothin' But A Maybe" on 1974's Rags To Rufus, and Bobby Womack's "Stop On By" later that year on Rufusized -- Chaka Khan & Rufus aimed for the quad-fecta with Rufus Featuring Chaka Khan closer "Jive Talkin'." It's a funny reversal of their to-that-point biggest crossover hit "Tell Me Something Good": Where that recording fit comfortably into the idiosyncratic melodic funk of songwriter Stevie Wonder, the secondhand synth-bass Stevie-isms the Bee Gees brought to "Jive Talkin'" are waved away in favor of a more laidback but hotter-simmering version. The biggest changes that don't involve replacing three Gibbs with three Chakas (a solid upgrade) is the way the groove is dampened from steady top-down/behind-the-wheel driving music to a slow strut. It's way too slow for disco, but good luck not finding a way to move to it anyways.

The Hebe Geebees - "Night Fever" (1978)

One of these days some enterprising and far more tolerant writer than myself is going to have to work up a taxonomical history of the Ironic Punk Cover. And when that time comes, you might want to point to late-'70s LA as the ground zero; the Dickies alone are probably responsible for enough to fill an EP ("Paranoid"; "Eve Of Destruction"; "Nights In White Satin"; "The Sound Of Silence"; the theme from The Banana Splits), with some of Black Randy and the Metrosquad's whiteboy funk covers thrown in for bad measure. Back when they were better-known for putting out Dr. Demento-fodder novelty compilations, Rhino Records got on both the punk-irony and disco-backlash bandwagons early with their 1978 compilation Saturday Night Pogo, a collection of irreverent and otherwise fucked-up punk songs (including Vom's "I'm In Love With Your Mom," sung by pioneering rock critic and Blue Öyster Cult patron/sometime songwriter Richard Meltzer) that closes with this "Night Fever" cover. The identity of the Hebe Geebees -- not to be confused with the British parodists with the similar name -- is kayfabed as "the most popular disco band in Pacoima" who decided to switch to punk when a member bought a copy of George Benson's double LP Weekend In L.A. only to find one of the records accidentally switched out for a Ramones album. In the real world, they were a bunch of hired hands that Rhino put together for a one-off, and none of the musicians involved, while credibly punk-adjacent, have been readily identified. Or blamed -- it doesn't feel much like they're trying in either the sincere or ironic senses, a one-riff joke that got old long before the song it's parodying does. Might as well turn to Gang Of Four if you want to hear punks doing disco, then.

Geraldo Pino - "5th Beethoven Africana" (1978)

Geraldo Pino's a strange case. The Nigeria/Sierra Leone-based musician born Gerald Pine began to hone an act in the early '70s that was heavily influenced by the singular funk showmanship of James Brown. And if "West African musician taking cues from James Brown to innovate a new style of African music" sounds a lot like Fela Kuti to you, well, Fela sounded a lot like Pino, or at least enough to give Pino credit for his gradual stylistic shift from a jazz/highlife hybrid to a more hard-hitting J.B.'s-laced Afrobeat. Of course, Fela's political agitation, outlandish personality, and all-time legendary music eclipsed Pino's in the end, though it wasn't simply the matter of some insurmountable gulf of quality between Pino's excellent recordings and Fela's entirely transcendent albums. Instead, it's the fact that Pino's discography is so frustratingly scarce. Only three of his albums have really made the rounds -- 1972's Afro Soco Soul Life, 1974's Let's Have A Party, and 1978's Boogie Fever -- all of which cost hundreds on the collector's market. And until recently, getting one meant keeping your fingers crossed that one copy of a thousand-pressed 2005 Soundway limited edition LPs of those first two fell into your hands. 1978's Boogie Fever was left out of that reissue program, but finally came out last year on Austrian rarity unearther PMG, and it's a far cry from the music he'd done earlier in the '70s that had him pegged as a formative Fela influence. Don't let the title fool you, though -- instead of merely "going disco" in the typical '70s tradition of veteran funk and R&B artists switching things up for the times, Pino concocted a strange halfway merging of synthesized disco and reggae rhythms, often pitting them against each other in unpredictable rhythmic structures that sometimes switch up without warning. His own tweak of Walter Murphy's "A Fifth Of Beethoven" has it both ways -- a loopy waltz-time intro/outro and a more straightforward 4/4 in the bridge -- to trip up unwary dancefloor inhabitants.

Alex Chilton - "Boogie Shoes" (1979)

There's no shame in digging KC & The Sunshine Band, really, but Harry Wayne Casey was always a far superior songwriter and arranger than he was a singer -- hear his songs delivered with the angelic smoothness of George McCrae or the boundless, joyful oomph of Jimmy "Bo" Horne's hollering, and it's really something to wonder what Casey could have ushered into the music world if he gave all his songs to people with that level of talent. And not necessarily that style of talent, either -- it wound up slayin' 'em in the hands of idiosyncratic Alex Chilton, for instance, who runs a hairsbreadth second to Chaka Khan when it comes to the best singer to take on a selection from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. Like Rufus, the former Big Star frontman's arrangement siphoned most of the disco out of the whole arrangement, albeit to vastly different effect -- sometimes interpreted by power-pop snobs as a rebuke of disco itself, but in reality more an acknowledgement of the B-side to the "(Shake Shake Shake) Shake Your Booty" 7" his son Timothee got a kick out of. And it's just the most preposterous, seat-of-the-pants thing, with an infamously mistimed first line from Chilton and a band -- led by pianist/producer Jim Dickinson -- making good on a choice to just play what they felt and let it all cohere through the magic of human error. Chilton plays guitar amateurishly and sings even more clumsily, but in that kind of way that people who know what they're good at try doing something poorly and find an entirely new way to express the latent feelings of bewildered rock 'n' roll mania that their more skillful expressions may not have been able to reach -- punk by circumstance, rather than choice or necessity. Ironically enough, it was Saturday Night Fever's success that halfway doomed Chilton's version of "Boogie Shoes": He'd originally recorded it in the spirit of messing around with a massive pop act's lesser-known deep cut, only to find it surging back onto the charts thanks to its appearance in the movie; he subsequently left it off American pressings of Like Flies On Sherbert where it had otherwise earned an enviable opening slot in an attempt to avoid looking like a bandwagoner. Who knows whether it might have changed the alternately bemused and perplexed what the fuck???!? reception it got from most Stateside publications if it was left on the LP to set the table for the rest of its notorious ramshackle brilliance.

Inamans - "How Deep Is Your Love" (1980)

That brief moment when reggae and disco actually legit collided was a surprisingly fruitful one -- just check out the baker's dozen worth of jams on this year's reissue of Soul Jazz's fantastic Hustle! Reggae Disco comp if you don't believe me (it's worth it just for that Risco Connection version of "Ain't No Stopping Us Now" alone). The Saturday Night Fever soundtrack wasn't immune to the benefits of the occasional lovers rock reworking, but while the stuff that was played relatively straight has its charms -- like Richard Ace's silky-sung, clavinet-tastic 1978 version of "If I Can't Have You" -- I'd be remiss in not taking a moment to highlight a track from the Black Ark itself that Lee "Scratch" Perry used to dance with the disco devil. 1980's Black Ark LP Volume 2 features a two-fer package of "How Deep Is Your Love," first as sung by the hopelessly obscure Inamans (a bit flatly, and with lyrics retrofitted to be about Jah), then with its bass-heavy but simplistic Pauline Morrison-produced riddim taken to the exosphere by Scratch and some well-deployed snare echoes. It's not the heavy classic material that the Upsetter reworked just a few years previous when he was working his wizardry on Junior Murvin and Max Romeo, but it's enough to add another dimension to an otherwise half-measure of a cover version.

Sky Creackers - "You Should Be Dancing" (1983)

Please don't ask me to explain the spelling of this one-off's group's name -- or much else about why this song is what it is. As much as even the most cursory skim of the Italo-disco genre's can turn up classic after classic, there's always the chance you'll run across something unexplainable, and not the fun weird incomprehensible kind of unexplainable, either. Sky Creackers were (if this means anything to you) one of the first acts to have a release on the Italo stalwart Memory Records label, with their version of the Bee Gees' '76 hit/SNF soundtrack selection "You Should Be Dancing" produced by label co-founders Alessandro Zanni and Stefano Cundari. This concludes the history portion of our blurb. Now for the critique portion: For a song that replaces all that mid-late-'70s disco instrumentation with Oberheim synth programming, it somehow sounds more dated than an original released seven years before, and whoever they got to imitate the Bee Gees does such an adequate job that they transcend absolutely nothing. They'd have been better off with a different singer entirely (maybe a vocoder?) to make a clean break from whatever 1976 remnants would have remained on the track -- as it is, it's a weird mishmash of two different generations of disco, a juxtaposition too recent for retro cred and too old for contemporary chic. Then again, if you bought this 12" in 1983 instead of what the Bee Gees were singing on that year, it's a perfectly understandable move.

Age Of Chance - "Disco Inferno" (1986)

Despite its pop-culture associations with all types of awkward uncoolness -- from Louis Tully's dorky party in Ghostbusters to David Brent's tryhard flailing in The Office to WCW's most irritating comedy heel -- the real place the Trammps' "Disco Inferno" holds in history is how Philly Soul staked its deepest and greatest claim to the surging genre that had built off its blueprint. Saturday Night Fever helped, naturally -- its inclusion on the soundtrack meant its #1 Billboard Dance Club Songs chart position in '77 was followed up by a #11 Hot 100 slot, a bonafide crossover success -- but the massive bust-out-your-speakers dynamic range and the steel-melting frenzy of Jimmy Ellis' lead vocal made it all feel like a foregone conclusion. Still, the song's reputation rose and fell with the reputation of disco itself, and by the time the '80s rolled around few pop stars short of a pre-Private Dancer Tina Turner had worked up the nerve to try and do it justice. So if you can't do it justice, you can at least do it dirty, as Leeds industrial electro group Age Of Chance did in '86. Aside from the historic import of their record sleeves being some of the first high-profile design jobs by the Designers Republic (of Warp Records and Wipeout fame), AOC landed on the map for an inventive if irreverent version of Prince's "Kiss" that topped the UK indie charts in late '86 while the original was still fresh in the pop chart's memory. And seeing as how their "Kiss" stuffed in all the possible clamor that His Royal Badness sacrificed to make the original's Mazarati-aided static-electricity minimalism spark -- or, as bassist Geoff Taylor put it, "removed the sex and replaced it with lump hammers" -- you'd expect their "Disco Inferno" to be similarly raucous. You'd be right, even if it's not in quite the same way: it plays out more like a paint-peeling Killing Joke/Jesus And Mary Chain hybrid of feedback and martial stomping, a bit closer to a vestigial limb of post-punk than the digital havoc of their more familiar Prince cover. Steven Elvidge makes for a hell of a lead singer (or "mob-orator," as he was usually credited), and the way he wails that "up above my head I hear music in the air" bridge would make John Lydon recoil in alarm.

Happy Mondays - "Stayin' Alive" (1991)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=8lqvtjAufUk

Oh, right: Then there's the song. For some reason, "Stayin' Alive" spent nearly 15 years either being played straight by easy-listening schlockmeisters, played the exact opposite of straight by Dr. Demento-courting goofs, and/or wrangled into several different languages, with only the occasional cross-genre rework (hi again, Richard Ace) to really distinguish itself. (This is where I could bring up the Grateful Dead teasing playing it during some shows in the late '70s, but that seems like it might be some sort of third rail of musical taste so I'll just let it go uneditorialized.) So who else would you entrust with the task of covering the most iconic song from an equally iconic film than one of the more iconoclastic groups to come out of the whole Madchester scene in the late '80s? Hell, the Bee Gees had to be a rock band before they were a dance band, but the Happy Mondays went out the gate as both at the same time, so why not have them go for it? There's a bit of ignominy in the timing of this one, of course: as the Australia/Japan-only B-side to the 1991 single "Judge Fudge," this is one of a handful of recordings the band put out between the triumph of 1990's career peak Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches and the 1992 crack-addled Barbados death-drive of Factory-shuttering disaster Yes Please! Neither A- nor B-side hint at the disaster to come -- it's an Oakenfold/Osborne production heavy on the hazy, dubbed-out, rhythmic must continue dancing throb of the band's best work -- but the switchblade-hippie menace/euphoria of Shaun Ryder's voice really seems to relish the opportunity to tear into the "life goin' nowhere/ somebody help me" outro -- only he centers it as a sort of recurring sub-chorus and reworks it as "we go nowhere/ we do nothin'," delivering it like the act of simply staying alive as the absolute most they could do. Which, for a while, it was.