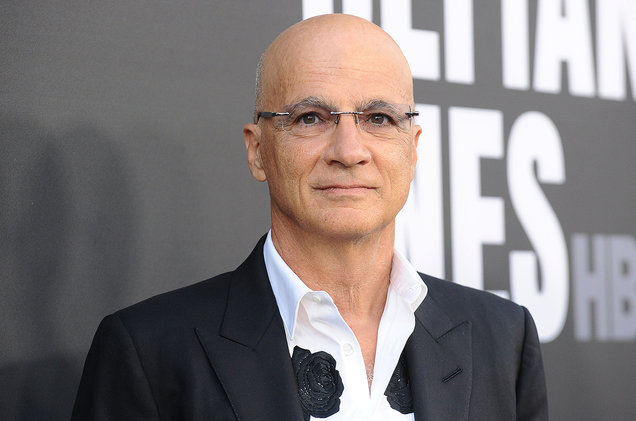

It's been three and a half years since Jimmy Iovine left his role as CEO of Interscope Geffen A&M to run Apple Music, but that doesn't keep him from thinking about the problems facing labels today -- or the rest of the industry for that matter.

Over a dinner recently at NeueHouse Hollywood in Los Angeles with Iovine and Allen Hughes, who directed the four-part documentary series, The Defiant Ones -- which focuses on storied careers of Iovine and Dr Dre., his partner in developing Beats Electronics -- a handful of journalists lobbed questions at and shared their thoughts with the iconic exec. The event was focused on the documentary's digital release last week and via Blu Ray on Tuesday, but subjects roamed often into the esoteric.

"No one's expressing how they feel," said Iovine, lamenting a lack of outspoken musicians willing to take a righteous stand. "People are telling us to dance, they're telling us to love, they're telling us to have sex ... but most people aren't talking about how we feel."

When Iovine turned his focus from labels to music-based tech in 2014, he left behind a legacy as the most successful head of a major label for the last 25 years. His rise to the top of the industry is chronicled in The Defiant Ones: from linking up as an engineer with Bruce Springsteen and John Lennon in the early 1970s, to producing Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Stevie Nicks and U2, to co-founding Interscope in 1990, where he signed Tupac Shakur, Nine Inch Nails, No Doubt, Marilyn Manson, Eminem and others. Meanwhile, Dre's story is told in a parallel narrative, until their lives became entwined with Dre's Aftermath Records imprint and, later, the Beats by Dre headphone brand that became Beats Electronic and Beats Music, all of which were sold to Apple for $3 billion in 2014. Iovine and Hughes were sure to clarify in conversation that the Defiant Ones title was not intended to refer to Iovine (though a case could certainly be made for his own defiance) but for the varying artists he worked with, many of whom appear in interviews during the documentary.

"When I was making the film, no bullshit, it was like a love note to something that never will be again," said Hughes after the conversation turned to social media and how un-"rockstar" frequent, revealing posts can feel.

"What an old man thinks, is like how there's a 13-or 14-year-old kid who's gonna see this thing and say, 'I want some of that,'" added Iovine, who's 64. "He's going to see Pac and Eminem and Bruce Springsteen and say, 'I want some of that.'"

Iovine continued, looking back on lessons learned since his early days working out of the control room in recording studios: "What I learned as a kid is in music, or any art, by far the most important thing happening at that moment is on that side of the glass. So I want Dre to be Dre, Pac to be Pac, Manson to be Manson, Trent to be Trent, Gwen to be Gwen, Mary J. Blige to be Mary J. Blige, I see it that way. There's nothing original about me, there's everything original about them. That's why I can't be in the record business right now, because there's not enough of that. So why do I want to do that?"

Conversation turned to Iovine's own sector of the industry and the folly of placing too much faith in tech -- particularly if you're a label.

"The streaming services have a bad situation, there's no margins, they're not making any money," he said. "Amazon sells Prime; Apple sells telephones and iPads; Spotify, they're going to have to figure out a way to get that audience to buy something else. If tomorrow morning [Amazon CEO] Jeff Bezos wakes up and says, 'You know what? I heard the word "$7.99" I don't know what it means, and someone says, 'Why don't we try $7.99 for music?' Woah, guess what happens?"

The short answer is it would rattle the entire streaming business ecosystem and probably most of all the industry-leading Spotify, which nine years after launching is still unable to turn a profit.

"The streaming business is not a great business," he continued. "It's fine with the big companies: Amazon, Apple, Google... Of course it's a small piece of their business, very cool, but Spotify is the only standalone, right? So they have to figure out a way to show the road to making this a real business."

Getting into the weeds, Iovine went on to point out labels' inevitable hardships over royalties derived from back catalogs amidst this new landscape. As rights for older catalog albums hit their contract reversion dates, it will be hard for labels to negotiate the type of splits they formerly took for granted. Likewise, on newer releases, artists are entering contract discussions with the leverage of millions of fans behind them already and getting better deals than ever before, he said, pounding his fist on the table to accent his point. "That's a great thing but what I'm saying is that everybody has got an issue ... the problem is not solved yet, the solution is not there. And I could poke holes in any of it, because I live it. And some of these things have got to be dealt with."

He continued, getting increasingly worked up, "Technology's position in life, to me, is like medicine. It's like science: see a problem, fix it. Don't think about what it does to anything else. The atom bomb: 'Oh we're gonna split an atom.' They weren't saying, like, 'People in Hiroshima are gonna die,' you know? The record industry doesn't know where technology is gonna go. In the past, technology has helped them. I'll give you a chain of events: The album, changed the business; cassette, 8-track, changed the business; CD, exploded the business; what was the next thing? Mp3 -- cut the business in half. So that can happen at any time. No one knows. Everyone still has to figure out their role, where they fit."

Iovine said that the business is "100 percent" overly optimistic about where things are headed. But it's not the price point that's the problem for streaming services. It's the free alternatives that are undermining the system in a way film and television streaming platforms are not forced to manage. He pointed to Netflix as a prime example, spending $6 billion on original content in 2017, while charging customers $9.99 or $11.99 for unlimited access to its unique offerings -- including TV and film they exclusively license. Meanwhile in contrast, by and large, all music digital streaming platforms offer the same material.

"So Netflix has all that original stuff and it's $11.99," he said. "Music, everybody has everything, plus the free tiers, every song is on YouTube, so how can they charge $11.99 to a consumer? I'm like, no. I'm gonna buy this and get the music for free.... It's a massive problem."

Even if it was solved, could that price point work?

"I don't know," Iovine replied. "I think if it was big enough, it could cost less. Put yourself in Kansas without a job and YouTube is free, Pandora is free, Spotify is free.... If there's a restaurant down the street with the exact same food as this restaurant that's on a mountain with a view, only this one's for free, a lot of people are gonna eat there. They'll use paper towels, they don't give a shit about napkins."

"These are issues that the record industry has to deal with and I don't know if they're dealing with it," he added matter-of-factly. "It's not my job."

Not anymore, at least.

This article originally appeared on Billboard.