Throughout the long and tumultuous history of the Smashing Pumpkins, there's never really been a prolonged period of anything resembling tranquility. There's never been a moment where they could actually bring themselves to sit back and enjoy their victory together. From the earliest days, there were breakups and addiction. There was Billy Corgan at the center, the dictator who had the vision to justify his control-freak tendencies, but who still wouldn't escape being called insufferable or delusional or megalomaniacal by his peers (and his bandmates). Sometimes you want the band-as-gang-of-friends mythology, sometimes you want the self-destructive band imploding for the sake of classic art mythology. The Smashing Pumpkins often tried to present the former, and excelled at the latter.

Ever since Corgan revived the moniker in the '00s, the topic of an original lineup reunion has never been far away. Today -- after a countdown clock, billboards of classic lyrics, and ice cream trucks -- the band finally confirmed they're back together. The Shiny And Oh So Bright Tour will kick off later this year, introducing us to a Smashing Pumpkins that puts Corgan, James Iha, and Jimmy Chamberlin on tour together for the first time in 20 years. Jeff Schroeder rounds out the lineup. The trek promises a celebration of the music from the Pumpkins' first run, from Gish through MACHINA. There are hints at a reunion album with Rick Rubin too.

That is, of course, a reunion without original bassist D'arcy Wretzky. Corgan talked plenty of shit about Wretzky over the years, and it was only in 2016 that they'd begun to speak to one another again -- yet another installment in the never-ending saga of finding their way to a reunion. Now, this version of a Smashing Pumpkins reunion has been naturally on-brand. There's been a lot of drama surrounding Wretzky's involvement, or lack thereof, and several shots fired back and forth between her and Corgan's camp. Even so, after all the characteristic in-fighting, we have the closest thing to a real Smashing Pumpkins onstage, together, in years, aside from Iha's occasional guest appearances alongside Corgan in recent times. For fans, there's still something potent in that.

This comes after years of consistent upheaval and subsequent teases of an actual original lineup reunion. Back on 2007's Zeitgeist -- the first album of the "reunited" Pumpkins era -- the only other original member playing with Corgan was Chamberlin. That was enough for some people. Give the idea of it a chance, they said -- after all, thanks to Corgan's penchant for re-recording his bandmate's parts, the Pumpkins' masterpiece Siamese Dream was primarily the product of him and Chamberlin anyway. Then Chamberlin was out of the band again, then back in again. It all becomes a bit hard to keep track of, and tiresome. This group's history is littered with these constant change-ups.

It was always tricky with the Pumpkins to begin with. The bit about Corgan re-recording parts for Siamese Dream is indicative of a much more fundamental aspect of this band: The Smashing Pumpkins were, at their core, Corgan's project, in the mold of today's indie auteurs who may or may not have a central cast of players acting as auxiliary characters. He envisioned it, he wrote all the songs. If 21st century Pumpkins was mostly just Corgan, maybe that wouldn't be such a big deal aside from the fact that 21st century Corgan grew into a nut who would go on Infowars to talk batshit conspiracy theories and the plague of social justice warriors with obvious madman Alex Jones.

Between the fact that it was always very much Corgan's ship to steer, how much these four people have fought with each other over the decades, and memories of the Pumpkins being a decidedly uneven live band during their peak era, all this fixation on the original lineup reuniting could seem, after a while, like an issue purely rooted in nostalgia, or in that kind of weird strain of fan loyalty where it isn't the "real thing" if all the right players aren't involved. That's only true for some bands; U2 has been the same four guys for four decades, they're not about to go tour with Peter Hook if Adam Clayton wants to retire. The Pumpkins, though? They were fractious and unstable from the beginning.

And yet, it still does mean something. Corgan may have always been the mastermind, and his particular songwriting gifts may have always been most rooted in a specifically youthful kind of pain, but maybe part of the reason his '90s writing was at such a different level was that he did take some kind of inspiration from the personalities around him, the friction. (In the band's nascent stages, his decision to pursue heavier music was partially triggered by Chamberlin -- the final addition to the group -- and his aggressive playing style.) Those four faces together onstage might've inspired something in the fans, too -- something beyond basic recognition.

Despite tons of young indie artists mining the '90s these past several years, it's not like bands such as Pearl Jam and Soundgarden have been major touchstones. Over the years, those grunge pioneers have been historically codified as classic rock, less so a younger generation that was dismantling tropes of the past -- as many of those bands in fact were -- but just another set of dude rock bands before the whole thing came crashing down in general. These guys were still misfits offering a voice and solace to a disenchanted and depressed generation, but in the grand scheme of pop history they were also still mostly white men with long, unwashed hair.

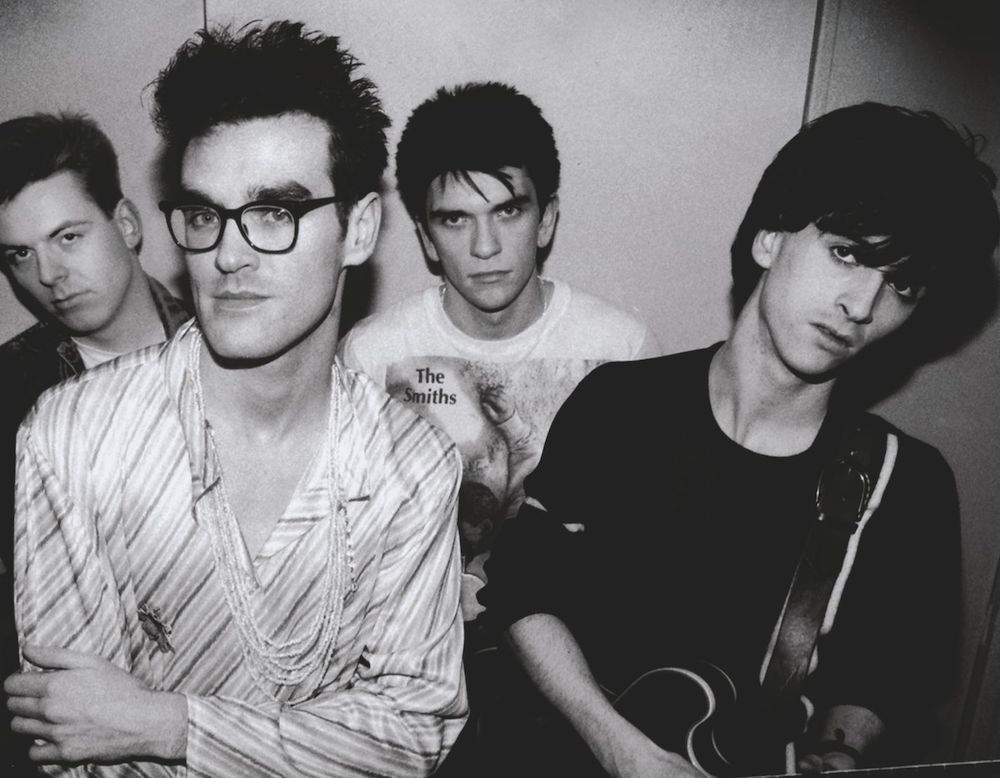

There was something different about the Pumpkins. Of course, the '90s also had L7 and Hole and riot grrrl and Sleater-Kinney. But the Pumpkins still had a more diverse lineup than the bands that were all white dudes, and there always seemed to be a bit of intention there. Like they were a band that was very much angling to give a wide variety of people someone to relate to. In addition to that, they were the outsiders and the weirdoes in a generation supposedly made of and entranced by the outsiders and the weirdoes: They were the goth-glam androgynous group with that gangly bald frontman. They were different, poster-children for the stereotype of the '90s alt-rock boom being for the people who were different.

Of course, their peers felt they were different, too: The Pumpkins were often disliked or lambasted by everyone from Soundgarden to Pavement for their unabashed careerism in an era when, you know, none of those other bands wanted anyone to hear their music, of course. Any of the big '90s rock bands were indebted to, and sang praises for, giant classic rock acts alongside their punk bona fides. But Corgan's version of alternative roots was the melancholic hits of '80s new wave. He was a Big Music kind of guy. A reach to, and shatter, the rafters kind of guy. Like Stone Temple Pilots, the Smashing Pumpkins were perceived as disingenuous in that milieu. They might've been the weird kids, but they had plain ambition. That wasn't OK.

This is something that still, to this day, seems to rankle Corgan. It isn't hard to find him taking shots at one of his old contemporaries, years after he's proven himself to be one of the last ones standing. He derided Soundgarden shortly after their reunion, though that's only one example in years of shade between the two. A couple years ago, he made the argument that he and Kurt Cobain were "the top two scribes and everybody else was a distant third," specifically focusing on Pearl Jam and Foo Fighters as his targets.

So the Smashing Pumpkins were the dysfunctional outsiders in a generation of dysfunctional outsiders, and maybe that's why we still put so much stock in the possibility of seeing Corgan, Iha, Wretzky, and Chamberlin regrouped. Those four, as fragmented as it all was, weathered a lot together, and through it they made some all-time great music. They made music that reached millions of people, listeners who saw some facet of themselves in this group and the pained songs they played. It isn't just about nostalgia, the image of the original band members playing all the enduring songs from when they were at the height of the powers. It's about restoring this band's name, restoring some percentage of that power.

On the occasion of all this Pumpkins talk and the impending new album, we decided to take a look back at the music that some configuration of these people have made together over the years. It's a rich catalog, well-deserving of revisiting and reappraisal -- Corgan made some very solid music in the latter years. It all goes back to their first several albums, however. Back then, Corgan was on that Noel Gallagher level, that genius that just keeps churning out indelible songs at such an insane rate that he eventually hits some kind of spiritual wall a few albums in. And, like with Gallagher, there's a lot to love about Corgan's work after his peak years. But nothing matches the weight and impact of what he did when he was young and furious and backed up by his three compatriots.

Corgan might've been an asshole with the "two scribes" comment, but he wasn't that far from being wrong. Ranking the Smashing Pumpkins' 10 best songs is a fool's errand. You could make the entire list from Siamese Dream and Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness and you'd still be missing several monster hits. You'd still be missing deeply beloved fan favorites. There are many famous and brilliant Smashing Pumpkins songs beyond the 10 below, but these are the highlights, the songs that can take you back to an older version of this band, that'll remind you why it could still matter that these four people could maybe, hopefully, all share a stage together again someday.

10. "Drown" (from Singles: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, 1992)

The Smashing Pumpkins' contribution to the soundtrack for Singles -- one of the most quintessentially early '90s documents tied to one of the most quintessentially early '90s films -- "Drown" is, appropriately enough, one of the band's most quintessentially early '90s compositions. Written shortly after Gish, it's something of a transition between their debut and the denser songs they'd craft on Siamese Dream. It has that fuzzy '90s intro, and the build from quiet to very, very loud. It's the finale, the second time the song erupts, that really makes it -- skillfully moving between its spacier passages and its indulgence of guitar fireworks, "Drown" was one of Corgan's first forays into building an epic that uses every dynamic and bit of space to deliver as much impact as possible.

9. "Rhinoceros" (from Gish, 1991)

There are a lot of great songs on Gish, from the raging "I Am One" to the lilting psychedelia of "Crush." Some might still consider it on par with the albums that followed. And, at least, it's a slightly overlooked classic in terms of 1991's alt-rock explosion, a predecessor to albums that eclipsed it like Nevermind, Ten, and Badmotorfinger. In that context, and considering what the Pumpkins later achieved, it's easy to look back on Gish as a strong early '90s LP that worked as a rough draft for Siamese Dream. But within that rough draft, Corgan was already a gifted songwriter, and he was already giving us some tracks that would stick around.

"Rhinoceros" is one of those tracks. It has both sides of Gish's personality, the beginning all cooing dreaminess and the second half a squall of distortion. In that way, it often feels not like just the best song from Gish, but also the most important -- the one that showed us what the Pumpkins really could pull off. This was the template, the sprawl, that presaged the greatness that would pervade Siamese Dream. The ending is prime Pumpkins, Corgan intoning "She knows, she knows" amidst all the guitars rising and swallowing him up.

8. "Ava Adore" (from Adore, 1998)

When I spoke to Corgan in 2014, he expressed some regret about how he'd positioned Adore ahead of its release. Back then, the Pumpkins were on top of the world, and strident about the idea that rock was dead and the future was electronic music. Adore was going to be their "techno album," then their "acoustic album," and then it baffled mainstream fans of Siamese Dream and Mellon Collie when it arrived and turned out to be both and neither of those things.

A misunderstood and still-underrated entry in the Pumpkins catalog, Adore did mark a musical shift, but more importantly it signaled a significant change in Corgan's writing -- he was no longer exhuming the intense demons of youth, but instead was digging into the struggles that only come with adulthood and aging. Death and loss hang over the album, resulting in some of the band's most fragile yet weighty material. There was the weathered pop of "Perfect," there were gorgeously twilit and lachrymose tracks like "Appels + Oranjes" and "Daphne Descends," a gentle storm that's more naturally haunting than many of the band's more explicit attempts at that mood.

The key highlight remains the album's throbbing, broodily anthemic title track "Ava Adore." There was always something about those verses that felt foreboding, maybe because of the uncomfortably squelchy groove or the fact that Corgan went Full Nosferatu in the video. But that chorus was always a slice of hard-fought brightness in an album that often remained in grey shadows. In the overall work of the Pumpkins, it was a masterful outlier like "1979" -- a song that was groove-driven and found Corgan successfully adapting his style into other forms. It became the skeleton key to Adore, both a perfect introduction to the tones and moods of the rest of the album, but also the subtle counterpoint, that chorus offering the smallest hint of hope outside Adore's dusky world.

7. "Disarm" (from Siamese Dream, 1993)

Most of Siamese Dream found Corgan climbing to new heights, perfecting the formula of early Pumpkins in towering songs with guitars upon guitars. Then, right in the middle, was this oddity called "Disarm," a song built on strings, acoustic guitar, and, um, bells. While out of left-field there, it foreshadowed the broadened palette Corgan would use on Mellon Collie two years later. For the moment, "Disarm" was also one of the emotional peaks on a very emotional album, somehow managing to be one of the most direct pop songs of the bunch while also being one of its saddest moments. You could break this down to acoustic guitar and voice and it'd be a straightforward, heartbreaking ballad; Corgan then gave it grandeur without overblowing it. In that sense, "Disarm" strikes a tricky balance that wouldn't always be present in the Pumpkins' catalog, and it remains one of the most affecting songs Corgan's ever written.

6. "Bullet With Butterfly Wings" (from Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, 1995)

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness is one of those wild-eyed, ridiculous rock albums where a singular genius went for it and, somehow, rather than getting lost in his own ego or talent or ludicrously ambitious vision, pulled it off. There are songs that do it all on that album, there are weird detours, and there are unprecedented leaps further into the polarities of the Smashing Pumpkins, songs of crippling beauty and songs of biting ugliness. As far as those gnarly rockers go, there are a ton of high points: the blistering "Bodies," the actually gorgeous "Jellybelly," the twin scathing behemoths of "Fuck You (An Ode To No One)" and "X.Y.U." There's the swaggering metal-glam of "Zero," with that immortal Corgan moment of "Wanna go for a ride?" and its patiently intensifying groove. Those are all deservingly well-known or fan-favorite songs from the Pumpkins' body of work, but there's one that symbolizes and stands above all of them, one of the band's most famous and instantly recognizable compositions.

"Bullet With Butterfly Wings" is iconic for a reason. When we think about '90s alt-rock, it's one of the signifiers. I mean, the lines Corgan sings here? "The world is a vampire." "Despite all my rage/ I am still just a rat in a cage." They are some of the lyrics that defined his career, let alone the '90s alt-rock boom. Sure, those same lines might make "Bullet" the kind of song you really feel at 15, and it might cede to more nuanced Pumpkins tracks as you get older. That is, after all, part of the point -- Mellon Collie being Corgan's proposed final outing in terms of cataloguing youthful concerns and angst.

Still: There are many, many great and caustic rockers in the Pumpkins' catalog. "Bullet With Butterfly Wings" remains important because of the fact that, no matter how many times you hear it, no matter how woven into the atmosphere and the history of the '90s it's become, it still hits you. It's a perfectly calibrated '90s rock song, and it's just as addicting as it was over 20 years ago.

5. "Tonight, Tonight" (from Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, 1995)

On the other side, there were Mellon Collie's moments of sheer, unbelievable beauty of the likes that the Pumpkins hadn't quite explored yet. Two of Corgan's greatest songs fall into this category, the airy ballad "Thirty-Tree" and the underwater dreamscape of "Cupid De Locke." Again, there's a song that sums up this side of Mellon Collie, and the band in general, perfectly: "Tonight, Tonight."

With the album's title track opener serving as instrumental prologue, "Tonight, Tonight" is the real beginning of Mellon Collie and, damn, is it ever an introduction. A huge, cinematic piece of work that also somehow became a widely-loved single, "Tonight, Tonight" is an orchestral swell that pulled back the curtain on the basic everything-ness of the album: It had wonder, and yearning, and sadness, and triumph, and mystery. Just how big could the Pumpkins go on their double-album followup to Siamese Dream? Just how far could they take that unabashed ambition? "Tonight, Tonight" was the answer and the mission statement, not only for the album but for their career. Itself a song that keeps scaling higher and higher when you think it couldn't go any further, it's a perfect encapsulation of what made Corgan tick at his mid-'90s peak.

4. "Thru The Eyes Of Ruby" (from Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, 1995)

If "Tonight, Tonight" suggested everywhere Mellon Collie would go, the album's monumental aspirations are epitomized in its two titanic epics, "Porcelina Of The Vast Oceans" and "Thru The Eyes Of Ruby." By this point in his career, Corgan had already proven himself adept at building up those emotive sagas. But prior to Mellon Collie, they were of a certain breed, weaving in and out of quieter retreats and giant, almost shoegaze-esque attacks of guitar. They were the sort of epics you could lose yourself in, drowning in all the distortion.

"Subtlety" and "restraint" aren't necessarily words we associate with the Smashing Pumpkins or with Corgan as a person, least of all when we're talking about a lengthy and packed double album. And yet, those were qualities that did set apart a lot of Mellon Collie from other chapters in the Pumpkins' career; Corgan knew exactly what kind of touch to bring to a wide variety of songs here. You can see his obsessive focus and attention at play on "Thru The Eyes Of Ruby," a multi-part journey that carefully deploys its transcendence over the course of nearly eight minutes.

From its aqueous beginnings, "Thru The Eyes Of Ruby" seems like it'll be an otherworldly thing, trafficking in a slicker version of the psychedelia from the earlier Pumpkins records. Then there are those thunderous guitar entrances, the way the song ratchets up into something more concrete and more dramatic, then modulates that energy over the rest of its run time, through the tension building to the final climax of "The night has to come to hold us young," before the song drifts out on the suggestive waves it first entered on. The whole track works that way, moving in and out of roaring human moments and more elusive and mystic ones. "Thru The Eyes Of Ruby" might not be one of the most famous Smashing Pumpkins songs from the '90s, but today it stands as one of Corgan's greatest achievements.

3. "Soma" (from Siamese Dream, 1993)

Next to -- and paired with -- "Disarm" to form the shattering emotional center of Siamese Dream, there's the album's monolithic centerpiece "Soma." Corgan located the platonic ideal, the fully-realized version, of his original self on Siamese Dream as an album overall, and "Soma" is the song that represents it, the song that does everything the Pumpkins did well in their earliest iteration.

"Soma" takes its sweet time unfolding, drifting through a pained but spaced-out first couple of minutes; like the name's reference point, it's a kind of narcotic haze, the burying of the wounds under chemicals. Then, of course, "Soma" bursts into the most glorious rupture Corgan ever crafted. People talk about catharsis in pop music a lot. "Soma" is the aural representation of it in its purest form. "I'm all by myself/ As I've always felt," Corgan sings as guitar lines lacerate across the track. For every listener who related to those words, it's a purge, simply hearing someone else say that -- and say it amidst such a sublime piece of songwriting, an intricate web of noise burning away at loneliness and numbness.

2. "1979" (from Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, 1995)

A lot of the biggest Smashing Pumpkins songs are alt-rock heavyweights that could find pop success in the specific landscape of the '90s. Not "1979." This is something completely different for Corgan, one of the moments where he wrote a straight-up, pristine pop song. It doesn't even necessarily jump out at first, but beyond sounding uncharacteristic for the Pumpkins at that point, "1979" actually succeeds by doing the exact opposite of what made their other songs. There are no guitar heroics; the groove is paramount here, but driven by a much simpler beat than Chamberlin's usual ferocity; there's little more drama in the chorus than anywhere else in the song, Corgan staying in as ruminative a mode as he is in the verses over those weird fluttering synths.

That's always the sound that defined "1979." The moment where Corgan went unabashedly pop is also a moment where he moved away from the more depressed and/or aggro themes of many of his other classics. Here, he favored something more universal across the generations: nostalgia. Those synths fly into reach and then right back out, the same way memories can linger on the tip of your tongue and refuse to let you clarify them, the same way you can almost grasp flickers of your past but know you'll never feel your hands wrap around it in quite the same way. That's the enduring power of "1979" -- it's a song we all know, even if you don't know the song itself.

Everyone has memories like this from childhood and your teenage years, the listless and searching and "figuring it out" chapters. We all knew someone like Justine. And, like the best and most sneakily written pop songs that directly indulge and grapple with nostalgia, it has the power to make you feel like it's about some other era you experienced, no matter how old you were or whether you were even alive in 1979 or 1995 or whatever. Gliding by, it sounds like the passage of years, the sound of being old before your time. Corgan wrote some of the songs that defined the '90s. With "1979," he transcended his context and wrote one of the pop songs for the ages.

1. "Cherub Rock" (from Siamese Dream, 1993)

One thing that was lost over time, even by Mellon Collie, was Corgan's ability, or at least desire, to write rock songs that were aggressive and anthemic and pummeling and affirming all at once. Eventually, those qualities got split into different veins, sighing pop songs vs. rock songs full of nastiness. That wasn't the case on "Cherub Rock." Here, Corgan bottled everything into one unimpeachable five minute song that was simultaneously a perfect hard rock song and a perfect pop song.

"Cherub Rock" is one of the great openers in rock and pop history. That means it, inherently, at once unveils the world of Siamese Dream to you while also only teasing where the album might take you later. But also, it's just baked into the actual structure of the song: The weird drumroll and clean guitar that you immediately know are a feint leading you up to some crushing intro, the moment the guitars do come in and it's just 20 seconds of seething distortion before the riff actually kicks in. Then the way that dinosaur of a riff keeps going underneath Corgan's wispy verse vocals. The pining in his voice in the chorus, a lyrical guitar solo as memorable as any of the song's vocal melodies, the way that bleeds into his climactic "Tell me all of your secrets" refrain, the way the song finally rides out into that same dinosaur riff once more. It's stunningly, impeccably crafted. "Cherub Rock" is the kind of thing you hear and immediately decide that you want more.

And, of course, there was a lot more. There was so much more on Siamese Dream alone, and that's before you get to the other highs of the Pumpkins' first era, the underrated MACHINA albums, the solid latter days. "Cherub Rock" was an early signal that there was a great songwriter in our midst, and it's not that Corgan never topped it, exactly. Corgan had many moments of brilliance after this. But there is something so gargantuan, so quintessential about "Cherub Rock," from its legendary intro to its sharp construction to its overflow of emotion and endorphins alike. There were few other moments in the Smashing Pumpkins that sounded exactly like "Cherub Rock," and yet it's also one of the defining Pumpkins songs. They were still a young band back then. But when you heard this, you instantly knew what they were capable of.

Listen to the playlist on Spotify.