Super Bowl weekend already feels like it was months ago, though there are still a couple feelings I've been coasting off in the last week-or-so since: one, it's always fun seeing Tom Brady fail, and two, people who want you to buy things act under the worst faith imaginable. All it took was that Ram truck ad featuring a bowdlerized excerpt from an MLK speech that explicitly called out the ill effects of advertising itself to justify the idea that Madison Avenue should be quarantined and fumigated until nothing remains except a few Volkswagen ads from the '60s. But why stop there when you can fuck with Bob Dylan?

Devlin's "Watchtower" is aggravating enough by merely giving existence to a recording of Dylan's words leaking feebly out of the mouth of Ed Sheeran. But using those words to sell some Tom Clancy's Corpse war-wank featuring John Krasinski as the decade's least convincing action hero while some of our most garbage-ass presidents tell us why perpetual war is actually good? Using Iggy Pop's "Lust For Life" in a Carnival Cruise ad clicks like Baby Driver by comparison.

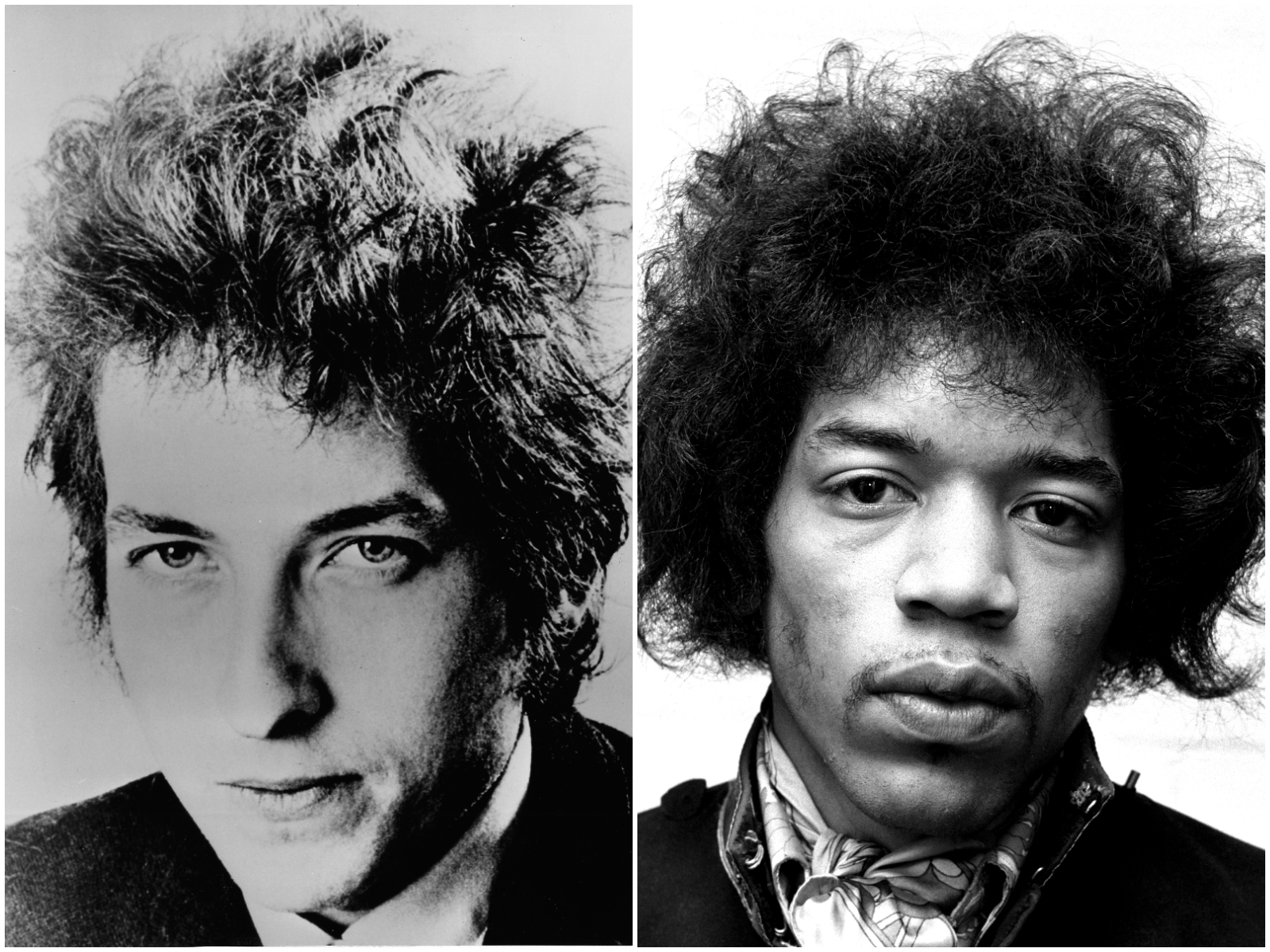

I guess that spurs the question, then, of what it means to try and cover "All Along The Watchtower" -- not just to put Bob Dylan's words in your mouth, but to try and put Jimi Hendrix's guitar in your rearview. Aside from what Aretha Franklin did with Otis Redding's "Respect," or to a lesser extent Soft Cell with Gloria Jones' "Tainted Love," few songs have been so thoroughly defined by a cover version as "Watchtower" while still allowing so much for the greatness of the original. But covers of it have been done far more than one might expect, given that double-layered reputation to live up to. And if outdoing both Dylan and Hendrix sounds like an intimidating task, that hasn't stopped a lot of bands from trying. Or a few of them from succeeding.

The Nashville Teens (1968)

For the most part, the Nashville Teens were neither -- they were from Surrey, and their hit "Tobacco Road" charted when a majority of the band members had hit their 20s. But there's nothing wrong with a little mythos, and given the dawn-of-rock icons they collaborated with in the early '60s -- Carl Perkins (on "Big Bad Blues"), Chuck Berry (as his backing band during a UK tour), Jerry Lee Lewis (backing him on the gasoline-fire classic Live At The Star Club Hamburg) -- their name felt more like an honorary gift than a lie. Still, they earned more renown as a backup band post-"Tobacco Road" than they did as their own thing, maybe because they had a reputation (and likely an actual habit) of being better interpreters than originals, which makes their status as the first band to cover "All Along The Watchtower" a curious cultural footnote. Released in March 1968 -- less than three months after Dylan's John Wesley Harding dropped -- the Teens' "Watchtower" falls in a very brief window where an electrified version of the song had no real precedent and could charge out in just about any form. That they still operated as a band untouched by psychedelia makes this cut so unique: It's the caged-in drama of the Dylan original as garage rock, still unsettled but not quite wailing in desperation.

The Brothers & Sisters (1969)

Forty-five years before 20 Feet From Stardom landed a Best Documentary Feature Academy Award, producer Lou Adler and conductor/arranger Gene Page got a choir of some of the most talented backup singers in the industry to record an LP of gospel-soul Bob Dylan covers, with Merry Clayton, Gloria Jones, and Edna Wright to sing leads. (Before you ask: Yes, one of choir members was Clydie King, who went on to appear on Saved and Shot Of Love, the latter two entries in Dylan's 1979-1981 "Born Again" trilogy.) And on an album that's a total Murderer's Row of choral singers -- chief amongst them Clayton belting out a spirit-catching "The Times They Are A-Changin'" the same year her appearance on the Rolling Stones' "Gimme Shelter" sealed her legend -- Honey Cone's Wright kicks the doors down with the most awestruck and shook-to-the-bone reading of "Watchtower," a performance that did for the lead vocal what Hendrix's did for lead guitar.

Bobby Womack (1973)

Even with his late-in-life career mini-renaissance, thanks to 2012's Damon Albarn/Richard Russell-produced indie crossover bid The Bravest Man In The Universe, it still bears reemphasizing just how across-the-board the genre-flouting performer Bobby Womack could be. Just going off his 1973 album Facts Of Life, one of his more cover-heavy albums, he engulfs the vintage, then 50-year-old blues standard "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out," gender-swaps the Goffin/King/Wexler classic "You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman," and does Bacharach/David's "The Look of Love," serving as a fantastic showcase of how, even at its most gravelly and intense, his voice can sound like velvet over the right sophisticated-soul arrangement. But his "Watchtower" closes out Facts Of Life with the best adaptation, a country-soul feeling that stretches from Nashville's skyline to across 110th Street as Womack turns the lyrics into a call-and-response with a guitar that sounds like it's intermittently catching its breath, only to hyperventilate all over again. In a 2012 Q&A with The Guardian, Womack stated that Hendrix's version set the benchmark for the 1960s, since he "made music like an abstract painting. Every time you listen to this song you hear something different that you haven't heard before." And Bobby makes damn sure to do the same with his voice here -- uncertain yet perceptive, desperate yet strong, and sly enough to sing that concluding line "the wind began to howl" with calm instead of intensity.

Spirit (1977)

Spirit aren't entirely forgotten, but for a band that was made out as a big-enough deal in their time -- for good reason, as a listen through their first four albums should remind you -- it's kind of surprising they never acquired the cult following of, say, fellow eclectic-psych Angelenos Love. And maybe the band's volatility in the face of being commercially underrated and jerked around by the industry has something to do with it: after the conceptual ambition of Twelve Dreams Of Dr. Sardonicus was met with a relative shrug, things fell to pieces, and bassist Mark Andes and songwriter/vocalist/percussionist Jay Ferguson jumped ship thanks to their frustration with talented but mercurial (and drug-damaged) guitarist Randy California. And by the mid '70s Spirit had gone through enough stop-start efforts at getting reunited that it almost became a grotesque parody of inter-band conflict. The breaking point involved a surprise visit by Neil Young, who attempted to join the band during a live 1976 Santa Monica concert for an encore of "Like A Rolling Stone" -- which Randy California saw as an intrusion by either a stranger he didn't recognize or a star he didn't want overshadowing his own comeback. California shoved Young offstage to the shock of the celebrity-strewn audience, and though the reasons seem justifiable in retrospect -- Young was drunk and still recovering from throat surgery, which meant his voice wasn't doing him any favors that night -- it was perceived as enough of an ego move on California's part that the band broke up again.

I bring all of this up because the next album to be billed under Spirit's name, Future Games: A Magical Kahauna Dream, is bizarre as hell: a Randy California solo album in all but name, featuring collaborations with Svengali garbage-monster Kim Fowley and strewn with recordings of TV audio from old Star Trek reruns, it's another psychedelic concept record dropped at a time when psychedelic concept records might have been at their absolute least in-demand. And while it's not a spectacular front-to-back listen, Future Games does have an odd echo of that Neil Young incident: another Dylan cover that hints back to California's teenage years jamming with a then-unknown Jimi Hendrix in New York in Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, only to miss out on a chance to join the Hendrix in London when California impertinently turned down Hendrix's amp during one of their shows. (That, and his folks didn't want him to go off to England at age 15.) With the dust from the rubble from his band's collapse still in his lungs and his mind still haunted by the what-ifs of the long-dead man who gave him his stage name, California's "Watchtower" is the sound of a man stretching beyond his capabilities -- in other words, his singing sounds like weak tea -- but it's also the sound of someone trying to get his shit back together, and that's one of the moods "All Along The Watchtower" accomodates perfectly.

XTC (1978)

XTC were irreverent nonconformists, even for that late '70s no-man's-land between first-wave UK punk and the New Pop that emerged at the turn of the '80s. That held true even in their formative years, which were a slapdash transition from late glam to all-enthusiasms-at-once mania ("anybody who'd done anything we liked," as Andy Partridge put it to Mojo, "I couldn't listen to it for years, but I'm nearly through the embarrassment"). Their '78 debut White Music was already staking claims as to what they felt about pigeonholes; their herky-jerky, nervy "This Is Pop" put its foot down on whether populism and iconoclasm could co-exist, then re-recorded it for a single and added an ambivalent question mark to the title. So naturally their "Watchtower" is something of a Devo-fication— Barry Andrews leaning on clapped out organ drones, Colin Moulding's two-ton tiptoe of a rattled funk bassline, Partridge's hiccupy freakout between harmonica solos. XTC would charge headlong into both more faithful forms of pastiche (word to The Dukes of Stratosphear) and more coherent forms of genre-bending, but post-punk covers more enjoyably janky than this one are hard to find.

U2 (1987)

Oof. If you want to fuse the vulnerable earthiness of Dylan's original with the anxious intensity of Hendrix's version, you could do worse than to get peak-hubris Bono belting to the cheap seats over it, but not much worse. By the time Rattle And Hum caught them on their Joshua Tree tour, U2's post-punk edge, or what was left of it, was getting dwarfed by their arena-filling ambition and the band's increasing sense that they had something deathly important to say about the roots of Great American Rock And Roll and their place in it. So when they weren't busy palling around with B.B. King or taking "Helter Skelter" back from Charles Manson, they were covering "Watchtower" as a kickoff to the glibly named free "Save The Yuppies Concert" -- a tongue-in-cheek goodwill gesture to the business sector still reeling from October 1987's "Black Monday" stock market crash, and a gift to San Francisco until Bono spray-painted the whatever slogan "Rock N Roll Stops The Traffic" on the landmark Vaillancourt Fountain. While the film juxtaposed this graffiti stunt with their "Watchtower" performance, Bono actually took up the Krylon during the closer "Pride (In The Name Of Love)," so the only crime committed during this cover of "Watchtower" is the way they turned it into an oversung, stiff-legged trudge-march to the center of Bono's self-importance. If you want to know why Achtung Baby had to happen, here's one of many good reasons.

Neil Young with Booker T. & the MGs (1992)

Sometimes I look at the roster of 1992's 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration and wish that there were more appearances by Dylan's potential successors to go with the ones by his contemporaries; aside from successive appearances by Mike McCready and Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam and Tracy Chapman, it's pretty heavy on Bob's boomer peers, and there's nothing as staggeringly fire-spitting as the Roots' version of "Masters of War," which might be the most king-sized motherfucker of a Dylan cover ever performed outside a studio. (It's not on YouTube, but hopefully their Bonnaroo '07 version gives you an idea.) Then again, the 30th Anniversary Concert has Neil Young during his post-Freedom grunge-elder-statesman comeback phase playing with one of the all-time legendary soul backing bands instead of Edward Sharpe And The Magnetic Zeroes, so I'll save my complaints there. Anyways, here's one of the most throat-clenchingly majestic/heart-wrenching sounds in rock, Neil Young's guitar at peak apocalypse, harmonizing with Booker T. Jones' organ. My complete review of this performance: Jesus fucking Christ.

Everlast & B-Real (2006)

My complete review of this performance is also Jesus fucking Christ, but, you know, the other kind. I feel bad for Dylan, Hendrix, and Cypress Hill all at once, though, which is kind of remarkable in itself. Fun note: this was recorded for the soundtrack of another Tom Clancy property, the video game Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter, and I don't know what the Clancy estate has against this song but goddamn, guys.

Eddie Vedder & the Million Dollar Bashers (2007)

Well hey, here's Vedder throwing elbows in the middle of a Dylan tribute again -- fifteen years after the first time, and now an Elder Statesman Of Rock himself, sprinkling hundreds of bespoke live albums in his wake en route to joining Dave Grohl in middle-aged grunger respectability. I admit that I lost a lot of enthusiasm for Pearl Jam somewhere between Vitalogy and No Code, which is coincidentally when I graduated high school (DISCLAIMER: yr author is old, just old as all hell), but I honestly can't stake a major claim as to why other than maybe I just got sick of Eddie's voice. And then along comes this song to test me: just what would it take for me to get excited about a song he's singing lead on? Because not only is this a cover version of one of my favorite Bob Dylan compositions, his band is not Pearl Jam -- it's Tom Verlaine, Nels Cline, Lee Ranaldo and Steve Shelley from Sonic Youth, and a few other people (Smokey Hormel, the Skunk Baxter of Odelay!) that I am more generally into than Pearl Jam. But while I can occasionally hear the Television in Verlaine's solos if I strain my ears, this version doesn't register much deeper than "here is a pretty straightforward alt-goes-tradrock performance of a song you've heard a bunch of different versions of, with Eddie Vedder sounding like Eddie Vedder on it." I feel like Michael Bluth opening the "DEAD DOVE - Do Not Eat!" bag.

Bear McCreary (2007)

I still haven't seen the rebooted Battlestar Galactica, but I've heard good things about it. Then again, I also heard good things about this version of "All Along The Watchtower," and it turned out to be a Kula Shaker-goes-buttrock dirge featuring an aggro-whine vocal that's the audio equivalent of an Ed Hardy Nehru jacket.