The prospect of Jonny Greenwood -- the notoriously spotlight-averse Radiohead multi-instrumentalist and classical composer -- in a tux at the Oscars is especially tantalizing to Phantom Thread director Paul Thomas Anderson.

"He said, 'Either you come and you're dressed like an idiot, and that'd be brilliant. Or you come and you have to say something on stage, which would also be brilliant. So win-win for me,'" Greenwood said in a recent interview. "It's a kind of abuse, really, the way he treats me."

Just as Daniel Day-Lewis' obsessive fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock and his muse Alma (Vicky Krieps) carve out their own twisted harmony in Anderson's sublime comic romance, so too have Greenwood and Anderson found an idiosyncratic equilibrium. Phantom Thread is their fifth film together. Since 2007's There Will Be Blood, Greenwood has scored all of Anderson's films (2012's The Master, 2014's Inherent Vice), and in 2015's Junun, Anderson documented Greenwood's trip to India to play with Shye Ben Tzur and the Rajasthan Express.

What makes them such a good match?

"Like any good long-term relationship, I'd say mutual respect and date nights," says Anderson.

"He has faith in me and he likes making fun of me," says Greenwood. "I think they're the two prongs of the perfect relationship, really."

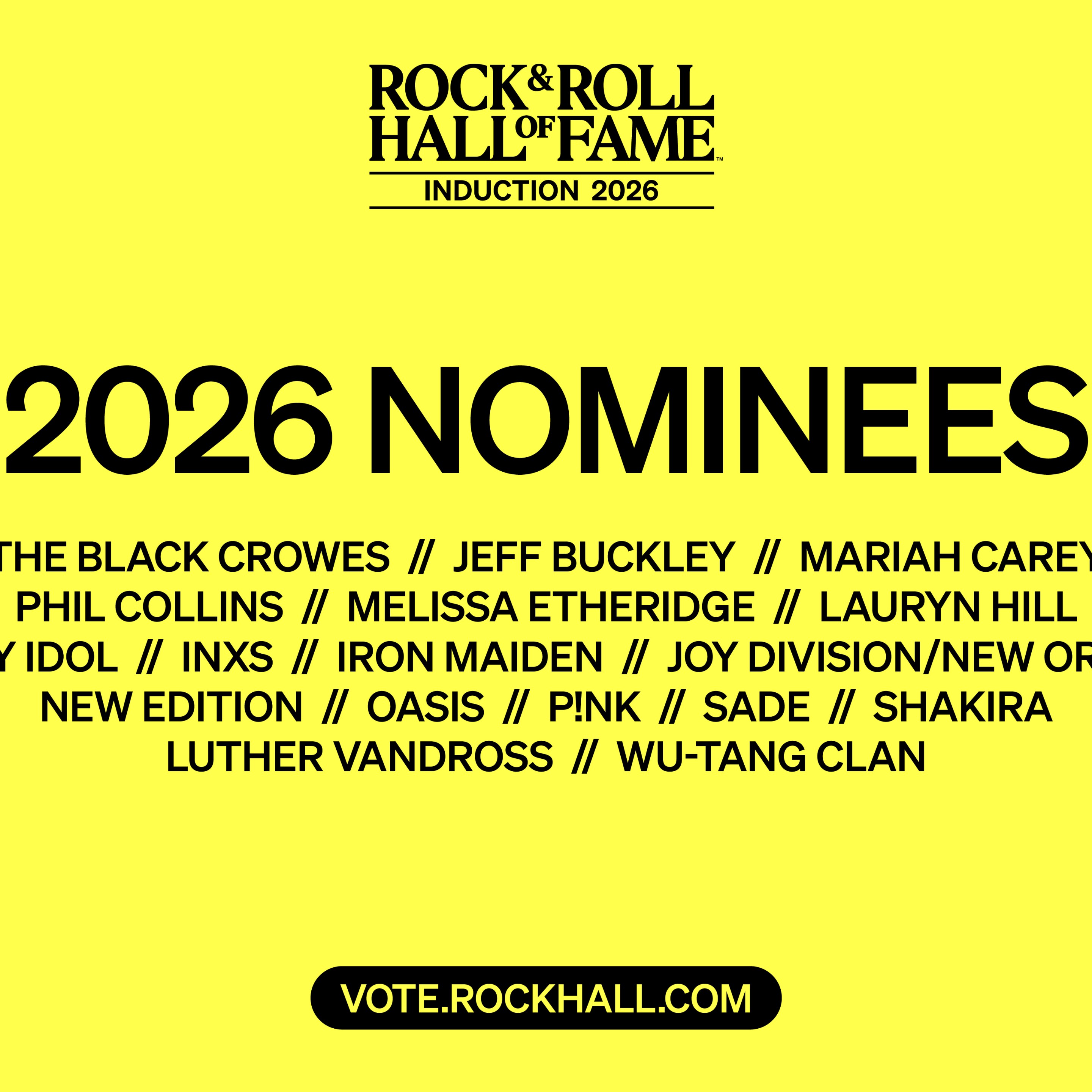

Phantom Thread marks a new crescendo for their collaboration and for Greenwood as a composer. The film is up for six Oscars, including best score -- Greenwood's first Academy Awards nomination. That, in itself, rights what many consider a grave wrong.

Greenwood's shrieking, unearthly music for There Will Be Blood is widely considered among the best film scores of the last two decades. But it was ruled ineligible for the Oscars because it was based partly on preexisting music: Greenwood's "Popcorn Superhet Receiver," a harrowing, dissonant piece in which Greenwood instructed the string section to play with guitar picks.

Phantom Thread is a love story, albeit a warped one, and it called for a more traditional orchestral score full of warmth and romance. Those are qualities not only uncommon to Greenwood's previous film work, but much of Radiohead's fraught and restless catalog, too. When Greenwood sent Anderson more typically dark music for the first scene, Anderson pushed him to write something more romantic. On the finished score, the first sounds you hear are 32 strings at once.

"A lot of the music I've done for other films has been quite mournful or frightening," Greenwood said speaking by phone from his home in Oxford. "I was a bit uptight about it and awkward about the fact that it's all genuine. What I kept thinking about is that feeling you get when you go to see a concert and you hear an orchestra start. Everyone gets quiet and the orchestra starts playing and you hear what the strings sound like in real life. It's amazing. It's like nothing else."

Greenwood spoke from a room that he said is filled with musical instruments, including the female Tanpura he brought back from India. He reckons he can play half of them. "It's like my adolescent fantasy has become real," he says. "It's an obsession. It drives my wife crazy. She wants me to have healthy ones, other ones. What can I do?"

Writing in praise of his There Will Be Blood score, the New Yorker's Alex Ross said Greenwood, who trained as a violist as a youth, is "better understood as a composer who has crossed over into rock." His initial forays into classical began with arrangements for Radiohead songs but has steadily grown. In 2012, he released a joint album with one of his greatest mentors, the avant-garde Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki.

Greenwood has grown more comfortable in his second act, which -- despite the magnitude of Radiohead's achievement -- is verging on overtaking his first.

"I suppose I'm more confident that stuff I've got on paper will sound how I imagine it will sound. I used to have to guess a lot more," says Greenwood. "There's still an element of that. I'm just a bit less cautious about it and more excited ... that's not the word. What's the word? Addicted, I suppose."

What Greenwood returns to again and again is the thrill of a live orchestra -- the complexity, the variation. He wrote the Phantom Thread score while traveling on Radiohead's A Moon Shaped Pool tour. It's an ideal time to write, he says, because of the large amounts of downtime and the ready access to pianos. He gives the pieces working titles like "San Antonio Slide" after the tour stops where they were composed.

Radiohead will find songs through constant reworking and experimentation, but Greenwood's classical work is solitary, on paper, leading up to a handful of days recording with an orchestra: "And then, suddenly, it's alive," he says.

Anderson calls Greenwood "equal parts authentic musical genius and total faker."

"He won't push gently into something that doesn't come naturally. He needs to find a legitimate way in to something rather than just juke-boxing. The music he came up with is just deeply felt -- by him, clearly. I don't know why some people can do it and others can't, but he can access something inside him and get it to come out though his fingers into his instruments. It's weird. He can even make Toca Band on his phone sound like something spectacular and moving."

In Phantom Thread, lush swells of strings surround delicate keyboard melodies. Among the standouts is the radiant, aching "Alma," one of the first themes Greenwood crafted. For inspiration, Greenwood tried to image what Woodcock would have listened to, settling on Glenn Gould's Bach recordings. Separated by a large time difference, Anderson describes music from Greenwood pilling up in his email overnight.

"I'll get music in the morning, when I wake up, let him know I have it. But by the time I make it in to the office to place it against the film, he's gone to bed," says Anderson. "Usually by the next day there's three new pieces in my inbox, each one more interesting than the last."

Much is known about Greenwood's musical passions but less about his taste in movies. "I like comedies, mostly," he says. "Some Marx brothers, Big Lebowski." Asked about scores he admires, the first titles that come to mind are predictably unpredictable: Laurence Rosenthal's Haitian-inflected score to the 1967 Graham Greene adaptation The Comedians, with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and trumpeter Don Ellis's throttling big-band score to 1971's The French Connection.

A few nights before the 3/4 Academy Awards, the Phantom Thread score will be played live alongside a screening of the film, one of a series of such concerts. When Greenwood spoke last week, he was intrigued but noncommittal about attending the Oscars: "I don't know yet, but it would be nice to go because Paul's going to be there," he said.

But last Friday, Anderson confirmed in an email that his dream of seeing a formally attired Greenwood on the red carpet will indeed be realized.

"He's coming!" wrote Anderson. "I have confirmation!"