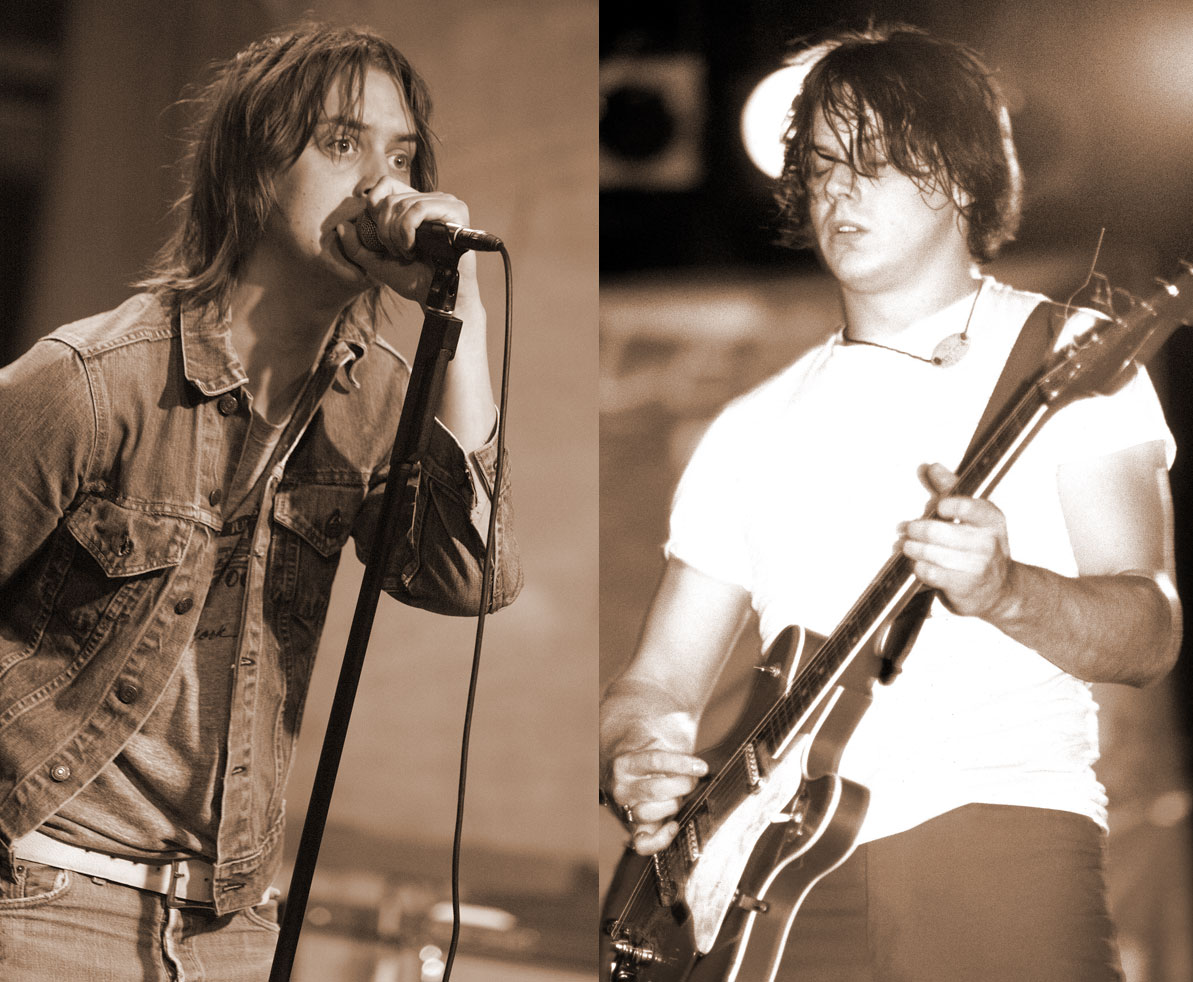

I was a churchgoing Goody Two-Shoes with a straight-A report card until my senior year of high school, when the Strokes and White Stripes turned me into an authority-spurning criminal.

In keeping with the repackaged rebellion of the so-called New Rock Revolution, the specific infractions against my parents and the state of Ohio were so minor that in a teen soap opera they'd be framed as comedic fodder rather than ominous foreshadowing -- which is to say even Seth Cohen, the patron saint of commodified 21st century rock movements, would not have blinked before engaging in such behavior. Still, as any upstanding young citizen will tell you, rules are rules, and these talented historical reenactors inspired me to break them.

The year was 2001. The Strokes were playing two hours up the road in Cleveland, and my parents said I couldn't go. Too much risk of bad weather in November, they explained. Maybe there was some unspoken post-9/11 paranoia in the mix too? But Is This It was my jam, and I would not be deterred. I clandestinely acquired a ticket, concocted a story about staying the night with my friend in a neighboring Columbus suburb, and counted the days until November 16. When that day came, my buddy David and I drove my boxy, gray 1988 Toyota Camry up I-71 to the Agora Theatre, making sure not to play any music by the night's headliners so as not to lessen the impact of the performance. We then stood through a set by local openers Uptown Sinclair (I shit you not), and waited for our heroes to emerge.

And when they emerged? Holy shit was it awesome. Was it more awesome because I lied to my parents about it? That's up for debate. What's not up for debate: It was so awesome.

Have you heard Is This It? It's basically a perfect album. Original? Of course not. Impeccable? I mean, you've heard the thing. The harmonic interplay between guitars, bass, and vocal; the "work hard and say it's easy" lockstep rhythms; the swaggering bellow communicating inspired, incoherent nonchalance. After downloading "Trying Your Luck" from Napster that summer, it did not take me long to become deeply obsessed. So did millions of other young people hoping to witness history, or at least history repeating. The album turned turned these scruffy rich kids into living legends and initiated a cultural tidal wave of likeminded retro-rockin' moppets. Its blurb on Apple Music reads, "Few albums in modern pop history can match the instant, game-changing impact of Is This It," and, yes, correct.

The Strokes' setlist that night in Cleveland consisted of all 11 tracks from the American version of Is This It plus "New York City Cops" (the album's proper, superior track 9, removed from the US release due to the aforementioned world-altering terrorist attack) plus "Meet Me In The Bathroom," which would later become a highlight from the band's sophomore effort Room On Fire and the namesake of a book you may have read a thing or two about.

Those are 13 incredible songs, and the Strokes performed them as loudly and emphatically as any teenage dweeb could want. It was euphoric. An instant halcyon memory -- which, come to think of it, is not such a bad way to sum up the Strokes' appeal in those early years, when they were being hailed as the antidote to teen pop and nu-metal. This streamlined convergence of critically acclaimed influences -- VU, Television, et al -- was supposedly real music for real music fans. That was a bunch of bullshit, but the Strokes were the truth.

Less truthful: I bought a T-shirt -- the one Shia LaBeouf later rocked in Transformers -- and hid it in my drawer for weeks until I could be certain my folks had forgotten about the Strokes concert, then told them I had purchased it at the record shop uptown. It worked! (Sorry, Mom and Dad.)

Fast-forward to March 2002. The White Stripes were playing Cleveland, too. This time no parental deception was required. I'm not sure what changed in four months -- driving at night on the freeway doesn't get any safer just because it's spring break -- but David and I were permitted to travel northbound once more to see Jack and Meg bash away in support of White Blood Cells (obviously the best White Stripes LP and I'm glad we can all agree on that and move on with the anecdote).

This album, too, had mesmerized me. It was rangy, raw, explosive, unpredictable -- the kind of record on which an absolute throttler like "Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground" is followed by the hootin', hollerin' "Hotel Yorba," on which twee balladry like "We're Going To Be Friends" could coexist with ripshit car-commercial chaos like "Fell In Love With A Girl." Throw in the mystique that came with their invented sibling backstory and strict red-and-white dress code, and the Stripes were a worthy Stones to rival the Strokes' Beatles -- never mind that Julian Casablancas, like his hero Lou Reed, never cared much for the Fab Four.

Speaking of which, by the end of the year Jack and Meg were opening for the actual Rolling Stones at arenas across America. As for their Cleveland club gig, it was roughshod and aggressive in keeping with the underground garage rock scene that birthed them, but it did not get my endorphins rushing with quite the same oomph as the Strokes show. (I always was a Beatles over Stones guy.) Thus, on the way home to I found myself behind the wheel struggling not to fall asleep. Being a dumbass kid, my solution for this drowsiness was to test the limits of the Camry's accelerator while blasting Doolittle by the Pixies. Could I push this old machine past 100 mph? I was delighted and bit terrified to learn that, yes, I could. Unfortunately, a member of the Ohio State Highway Patrol took notice, and I ended up with the first of many speeding tickets in my life. I would have been on the hook for reckless operation, too, if not for the generosity of this particular cop.

There I was: a liar and a lawbreaker, all in the name of rock 'n' roll. If this assessment seems, I don't know, overdramatic, so was the hoopla surrounding these groups. Not that the Strokes and Stripes were anything less than revelatory, but with precious few decades of perspective at my disposal, even as I read up on the critical debates about their authenticity I couldn't fully appreciate how absurd the narrative around them was. Here were all these "the" bands -- Strokes, Stripes, Vines, Hives, motherfucking Mooney Suzuki -- arriving just in time to save music with their haircuts and color schemes and analog recording. Death to Fred Durst and Britney Spears, long live Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, or something?

What was clear to me was the groups fronted by Casablancas and White were the best of this bunch by far. I was so enamored that I grew out my hair into a Strokes-inspired poof, preserved for posterity on my college student ID, and later dressed up as Jack White for Halloween. Many people my age shared this reverence, as did some of our parents. The Strokes and White Stripes very quickly became rock royalty. For a generation of young garage rockers, they were heroes, gateway drugs, and guiding lights, every bit as meaningful as their 20th-century inspirations. For Boomers, they were a welcome blast from the past, a lifetime of memories distilled into something more comprehensible than Korn.

The Strokes' legacy was so instant and so resounding that in the gap between 2006's moment-concluding First Impressions Of Earth and 2011's convoluted comeback Angles they somehow achieved lifetime festival headliner status. In 2016, Pitchfork's Jeremy Gordon correctly argued that the Strokes had become classic rock, meaning they "can recycle their iconography without losing their edge, as far as casual and younger listeners are concerned." Many people are more interested in recycling it than the actual band members are; folks still pile onto festival grounds in hopes of hearing "Hard To Explain," and the world's rock bars and entry-level corporate venues are still crawling with combos whose entire existence is an extended act of Strokes worship.

The Stripes' trajectory was steadier, their vitality longer-lasting. They built an almost flawless discography. They never fell off. And when they officially parted ways in 2011, most of the goodwill they'd accumulated transferred to Jack White's solo career and assorted side projects. He, too, can emerge to headline fests whenever he pleases -- and if the White Stripes ever reunited it would be the biggest rock 'n' roll storyline of the year. For now he's ditched the visual gimmicks of his salad days, but the quirky retro student-become-master ethos remains the same. Historically he has shown little interest in shaking his profitable reputation as the Last Rock Star Standing.

White and Casablancas, the reigning icons of that post-Y2K garage rock resurgence, have walked disparate but in some ways parallel paths in the years since they were sharing headlines and co-headlining Radio City Music Hall. After First Impressions Of Earth crash-landed, Casablancas vacillated between half-hearted Strokes releases (LPs in 2011 and 2013, an EP in 2016) and passion projects seemingly closer to his heart: an electronically infused 2009 solo album called Phrazes For The Young, a 2014 experimental mindfuck with his new band the Voidz titled Tyranny, an increasingly active boutique label called Cult Records largely populated with Strokes worshippers. He's also produced a handful of records and collaborated with artists as diverse as the Lonely Island, Daft Punk, and Savages' Jehnny Beth.

Despite all the activity, there was a marginal quality to the life Casablancas chose. He moved upstate to avoid NYC brunches and raise a family. He got way into politics, espousing theories about the way the world works that seem at once simplistic and convoluted. He mostly seemed to exist inside his own head, or at least his own bubble.

White, too, built himself a private empire, but he did so in a far more public way. He released a pair of solo albums, both of them big hits in the vinyl market and on alternative rock radio. He spearheaded a couple other alt-rock staples, first the Raconteurs and then the Dead Weather. He built Third Man Records into a booming business comprising a label, performance space, record plant, and several retail storefronts. He contributed to documentaries, tributes, and all things old-timey, continually advocating for an old-fashioned approach to music and life. He enjoyed very specific guacamole and maybe didn't enjoy a trip to Wrigley Field.

Unlike Casablancas, White also ventured increasingly close to the mainstream. He co-founded Jay-Z's oft-ridiculed streaming service, Tidal. He appeared on 2016 blockbuster albums by Beyoncé and A Tribe Called Quest. His feuds with the Black Keys and ex-wife Karen Elson made him somewhat of a tabloid figure. Inadvertently, the riff from his White Stripes hit "Seven Nation Army" became one of the world's most popular sports chants.

Now, almost two decades after their initial spotlight moment, these two rock stars bound together by history find their careers crossing paths again. Casablancas has a second Voidz album called Virtue out at the end of the month on Cult, a project every bit as sprawling and scattershot as the previous effort but with more magnetic composition. White's third solo album Boarding House Reach arrives a week before via Third Man, and he's touting it as his plunge into the world of modern music. Polarizing new songs and eyebrow-raising interviews are trickling out from both camps. For the first time since maybe the Elephant and Room On Fire rollouts of 2003, the echoes between their careers are crystallizing before our eyes and ears.

Their convergence is not as exhilarating as it used to be. Not that White and Casablancas have completely fallen off: Advance Boarding House Reach track "Over And Over And Over" dates back to the White Stripes era, and the bastard just rips, punctuating its violently snaking guitar work with bizarre choral breaks. Virtue opener "Leave It In My Dreams" is like an old Strokes gem teetering on the brink of memory, its odd sonic outbursts never obscuring its essential pop appeal. These dudes are still giving us glimpses of the gifts they built their respective legacies on.

Yet what's been most acute throughout these rollouts is each icon's interest in leaving those legacies behind. You can hear it in the way they talk about the bands that made them famous: Casablancas comparing the Strokes circa now to the paycheck work Hollywood actors take on in between serious artistic pursuits, White telling Rolling Stone that "there is a case to be made that in a lot of ways, the White Stripes is Jack White solo." You can hear it even more in the music they're releasing, tunes that painstakingly aim to be weird for weirdness' sake. They both seem tired of carrying around the weight of the cultural moment that made them, eager to demonstrate how much they've grown as people and musicians.

Given the way the Strokes' career went, this phenomenon has been manifesting in Casablancas' life for far longer, which has resulted in music and pullquotes way more out-there than anything White is serving up. He's so frustrated with "maximized-for-profit, scientifically tested music," as he describes it to Billboard, that he's become obsessed with trying to "push the boundaries" -- hence the zonked galactic weirdo splatter that comprises his output with the Voidz. Only the most loyal fan would suggest this willfully confrontational music matches the thrills of, say, "Reptilia," but there's some genuinely inspired stuff burbling in the morass.

Casablancas' repeated attempts to drop truth-bombs on interviewers have been less successful. In a Rolling Stone podcast Casablancas sings the praises of "obviously" pro-Putin propaganda network Russia Today, positing it as some sort of Trojan horse for anti-Russian activists. In a much-circulated New York interview, he dismisses standard notions of musical accessibility as "cultural brainwashing," argues Jimi Hendrix wasn't famous during his lifetime, suggests David Bowie was only about as big in the '70s as Ariel Pink is now, and wonders aloud, "Can you make complex truth sexy?" He cannot. Over and over, he expounds on politics and the global economy with the confident expertise of a college freshman.

In Conversation: Julian Casablancas pic.twitter.com/b2IKefJ2GL

— coolin (@colinjjoyce) March 12, 2018

As for White, he's out here in Rolling Stone admitting he uses the digital recording software Pro Tools now -- apparently a remark from Chris Rock incited an existential crisis about White's lifelong devotion to the time-honored recording methods of the ancients. White further explains that his former dismissals of hip-hop were merely symptoms of the contrarianism his role as an artist demands -- all part of "Offend[ing] In Every Way." Unsurprisingly, he admires the popular YouTube philosopher Jordan Peterson but says he hasn't heard about the guy's controversial views on feminism and gender, just his bits on religion. Oh, and White has a lengthy rant about his "love-hate relationship with nurses" that dates back to his days touring with Meg. Even as he abandons his old sticking points, he remains stubbornly cantankerous.

White's new music parallels his new press tour in bending over backwards to show how far he's advanced. In both contexts, he's clearly the same old White, but with some modernized window dressing. Based on the singles he's released so far, the approach works better in interviews. His attempts to shoehorn computer music and other new flavors into his well-established songwriting templates feel forced -- which is weird considering how broad his creative vision has always been. Maybe Boarding House Reach holds together better as a whole, but it's shaping up to be, at best, one of those oddities that adds texture to a long and winding discography.

Who can really blame White and Casablancas for all this restlessness, though? It's a story as old as rock stardom. Worldwide fame at such a young age inevitably warps a person, saddling them with a weight of impossible expectations and allowing them to surround themselves with people who'll affirm their every impulse as inspired. The phenomenon is surely even more paralyzing when the music you've been hawking your whole life is deeply rooted in the past. David Byrne, for example, has been able to evolve so gracefully in part because the ethos surrounding his music has always been one of forward advancement; although they emerged from the CBGBs scene, another back-to-basics rock revival of sorts, Talking Heads were touted as a fresh alternative to the retro-minded punk rockers. In contrast, the Strokes and Stripes leaders met the same fate as one of the butt-rockers they supposedly vanquished: They've created their own prison.

Look: Reliving your glory days can be fun. I've got plenty of old concert stories like the ones detailed above, and I very much enjoy regaling whoever will listen with these and other highlights from my youth. But I am glad no one expects me to make this kind of nostalgia the main focus of my life. In fact, social courtesy requires that I not become the kind of guy who spends all his time living in the past, subjecting everyone in earshot to tales of the good old days. For that reason, I am inclined to sympathize with my rock 'n' roll heroes of yesteryear if they want to believe their best days are still ahead of them. I'm just not inclined to agree.