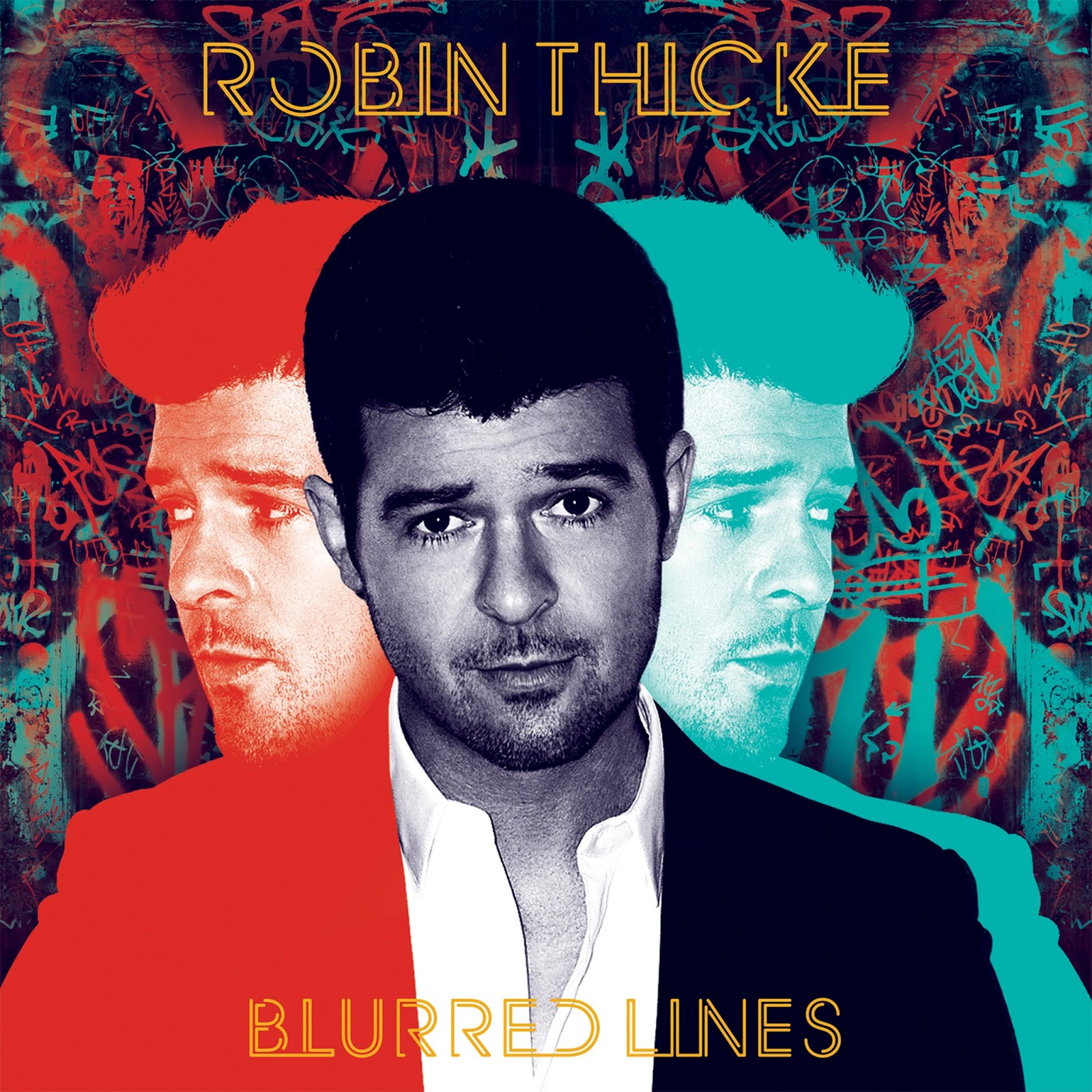

A jury's 2015 verdict punishing Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for infringing Marvin Gaye's "Got to Give It Up" to create the international chart-topper "Blurred Lines" was a controversial one in the musical community with some believing that the $5.3 million judgment would chill musical creativity. But on Wednesday, a divided panel at the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals largely affirmed the verdict in a lengthy decision that provides a huge win for Gaye's family.

The majority opinion from Circuit Judge Milan D. Smith Jr. rejects the Thicke camp's argument that Gaye's copyright is only entitled to "thin" protection, commenting, "Musical compositions are not confined to a narrow range of expression."

Smith looks at the 1909 Copyright Act, which was the law until the mid-1970s and didn't protect sound recordings. "Got to Give It Up" was one of the last songs created before the law was amended, and as such, the trial judge decided that only the sheet music deposited with the U.S. Copyright Office was entitled to protection. The 9th Circuit, however, decides not to resolve the question of whether the scope of Gaye's copyrights was limited to the sheet music.

Nor will the appeals court disrupt the trial judge's decision not to allow the jury to hear the actual sound recording with cowbells and party noises. Additionally, the appeals court affirms the trial judge's discretion in allowing testimony from Gaye's music experts, which the defendants asserted illegitimately incorporated opinions about the similarity of the sound recordings.

Ultimately, the majority opinion (read here) states that the verdict wasn't against the clear weight of evidence and won't disturb fact-finding at trial and second-guess the jury. The affirmation of what happened three years ago is on narrow grounds.

"We conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in denying the Thicke Parties’ motion for a new trial," writes Smith.

A good part of the appellate discussion is directed at damages where the jury awarded 50 percent of publishing revenue for "Blurred Lines" as actual damages. That amounted to nearly $3.2 million and the appeals court says that testimony from an expert regarding this wasn't speculative. Additionally, the trial judge and jury awarded profits in the amount of $1.8 million against Thicke and $357K against Williams and the conclusion by the 9th Circuit is that the award wasn't clearly erroneous. The Gayes also will be able to get a running royalty rate of 50 percent.

Where the appeals court differs from the trial court's judgment is with respect to some of the lesser players, including rapper T.I (aka Clifford Harris Jr.), who was cleared by a jury before being punished by U.S. District Judge John Kronstadt.

"Harris and the Interscope Parties contend that the district court erred in overturning the jury’s general verdicts finding in their favor," writes Smith. "We agree. First, the Gayes waived any challenge to the consistency of the jury’s general verdicts. Second, even had the Gayes preserved their challenge, neither Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 50(b) nor our decisions in Westinghouse and El-Hakem v. BJY Inc., conferred authority on the district court to upset the jury’s verdicts in this case. Third, as to Harris specifically, the district court erred for the additional reason that no evidence showed Harris was vicariously liable."

Thus, T.I. gets a win today.

The decision offered a sharp dissent from Judge Jacqueline Nguyen and a rebuttal from Smith and Judge Mary Murguia.

Nguyen blasts the outcome.

"The majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style," she writes. "'Blured Lines' and 'Got to Give It Up' are not objectively similar. They differ in melody, harmony, and rhythm. Yet by refusing to compare the two works, the majority establishes a dangerous precedent that strikes a devastating blow to future musicians and composers everywhere."

She continues by addressing the experts.

"While juries are entitled to rely on properly supported expert opinion in determining substantial similarity, experts must be able to articulate facts upon which their conclusions—and thus the jury’s findings—logically rely," states the dissent. "Here, the Gayes’ expert, musicologist Judith Finell, cherry-picked brief snippets to opine that a 'constellation' of individually unprotectable elements in both pieces of music made them substantially similar. That might be reasonable if the two constellations bore any resemblance. But Big and Little Dipper they are not. The only similarity between these 'constellations' is that they’re both compositions of stars."

Nguyen then runs through guiding principles for copyright law — that expressions are protected but ideas are not, and how this gets applied under the instrinsic and extrinsic tests used to measure similarity.

"The majority begins its analysis by suggesting that the Gayes enjoy broad copyright protection because, as a category, '[m]usical compositions are not confined to a narrow range of expression,'" she writes. "But the majority then contrasts this protected category as a whole with specific applications of other protected categories—the 'page-shaped computer desktop icon' in Apple Computer (an audiovisual work) and the 'glass-in-glass jellyfish sculpture' in Satava (a pictorial, graphic, and sculptural work) —that were entitled only to thin copyright protection due to the limited number of ways in which they could be expressed. That’s a false comparison. Under the majority’s reasoning, the copyrights in the desktop icon and glass jellyfish should have been broad. Like musical compositions, both audiovisual works and pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works can be expressed in myriad ways."

The dissenting judge thinks the majority should explain which elements of "Got to Give It Up" were protectable and doesn't think that just because Gaye's song was widely available, there was a lesser burden to show similarity.

This all picks a fight with Smith and her colleague about procedure given the case is being reviewed de novo (basically with fresh eyes) but without particular trial motions the majority feels are necessary.

"The dissent’s position violates every controlling procedural rule involved in this case," states the majority opinion. "The dissent improperly tries, after a full jury trial has concluded, to act as judge, jury, and executioner, but there is no there there, and the attempt fails."

Essentially, Smith thinks the appeals court is hand-cuffed from doing much about what the jury found after resolving factual disputes, especially because the defendants failed to make a motion for judgment as a matter of law at trial.

"Two barriers block entry of judgment as a matter of law for the Thicke Parties," writes Smith. "The dissent attempts to sidestep these obstacles: It finds that the Thicke Parties are entitled to judgment as a matter of law, but fails to explain the procedural mechanism by which this could be achieved."

But eventually, the majority gets to the discussion that many in the musical community begged the appeals court to take up given the rash of copyright lawsuits over musical compositions in the time since the verdict. Smith isn't impressed.

"[T]he dissent prophesies that our decision will shake the foundations of copyright law, imperil the music industry, and stifle creativity," comments the judge. "It even suggests that the Gayes’ victory will come back to haunt them, as the Gayes’ musical compositions may now be found to infringe any number of famous songs preceding them. Respectfully,hese conjectures are unfounded hyperbole. Our decision does not grant license to copyright a musical style or 'groove.' Nor does it upset the balance Congress struck between the freedom of artistic expression, on the one hand, and copyright protection of the fruits of that expression, on the other hand. Rather, our decision hinges on settled procedural principles and the limited nature of our appellate review, dictated by the particular posture of this case and controlling copyright law. Far from heralding the end of musical creativity as we know it, our decision, even construed broadly, reads more accurately as a cautionary tale for future trial counsel wishing to maximize their odds of success."

This article originally appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.