I only saw Pulp once. A few weeks after they released This Is Hardcore, the much-anticipated follow-up to their critically beloved and UK-conquering breakthrough Different Class, Pulp came to America to play at the second day of the Tibetan Freedom Concert in Washington, DC. That was a day full of enormous names, and a football stadium full of kids there to see those enormous names. Nobody was there to see Pulp. Pulp played early in the day, along with the rest of the Beastie Boy buddies and cred-boosters -- after Money Mark, before Sonic Youth. They only played three songs, two then-new ones and "Sorted For E’s And Whizz." No "Common People." And then they were gone.

I was befuddled. Pulp were never much of a threat to break through in America the way Oasis had done. Their sound was too haunted and cerebral and definitively British. Still, this Tibetan Freedom Concert had to be their biggest American show ever, right? A whole football stadium full of kids! A captive audience! And sure, they were there to see the Beastie Boys and Pearl Jam and R.E.M. and Radiohead, but why would Pulp not at least attempt to wow them? Why, for example, would they not play the one massive and incredible song that at least a few people in the audience might've recognized? It all seemed so willfully perverse. But then willful perversity, I would learn soon enough, was pretty much Pulp's thing in 1998.

Different Class made Pulp into stars. This was a surprising development. Pulp had been around forever, coming from a desolate Northern English city and releasing album after album of dour, withering music. They'd had some unlikely pop success with 1994's His 'N' Hers, but even after that, Different Class did not sound like a breakthrough. It's a lush, layered, finely observed collection about caste-system resentments and romantic obsessions and K-hole depressions. It was not built to compete with Blur or Oasis. And yet it was so good, and Jarvis Cocker had grown into such a compelling and charismatic frontman. When Pulp headlined Glastonbury that summer, the last-minute emergency replacements for a just-broken-up Stone Roses, they had their coronation: significantly more than 20,000 people standing in a field and singing along with "Common People." So of course, Pulp had to torpedo all that momentum immediately.

The first thing we hear on This Is Hardcore is a luxuriously tense guitar-drone. Then it's Cocker haltingly stage-whispering about "the sound of loneliness turned up to 10." As thesis statements go, you could do a lot worse than this: "This is the sound of someone losing the plot / Making out that they're all right when they're not." Before long, gospel-choir backing singers come howling in, and hovering-UFO theremins, and Cocker is warning about when "you're not longer searching for beauty of love, just some kind of life with the edges taken off." The stress just builds and builds, and Cocker dances with it, almost laughs at it. There's still lots of chatter about how This Is Hardcore was the album about the end of the Britpop era, the musical Altamont moment when all of the UK's cocaine swagger and optimism came crashing down. But "The Fear" doesn't sound like it's about the end of Britpop. It sounds like it's about the end of everything.

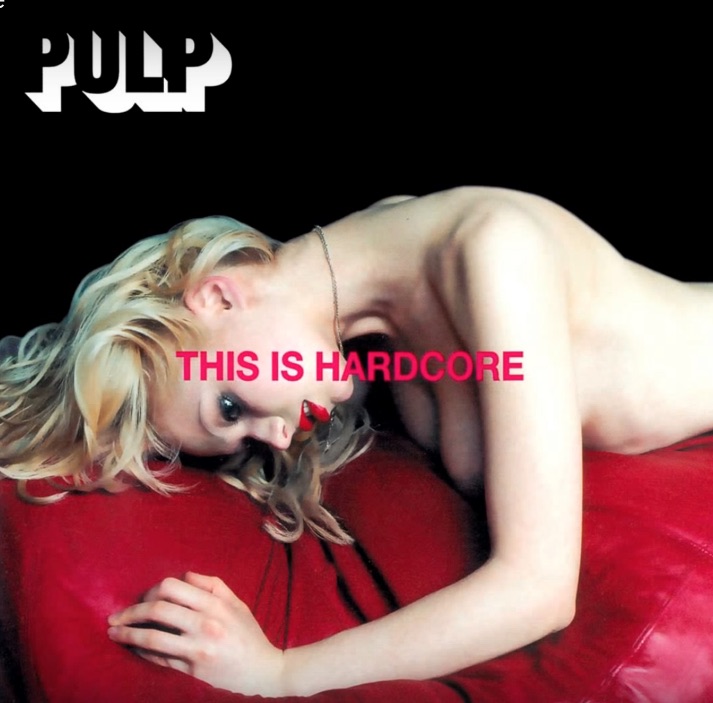

"The Fear" is an overwhelming, climactic bum-out of a song -- which is to say that it set the tone for the rest of This Is Hardcore. With their new platform as Britpop standard-bearers, Pulp became doomsayers, sneering at the partied-out wasteland that they saw in the culture around them. Pulp did not find anything exhilarating in stardom. Cocker, already in his mid-30s, was much older than most newly minted stars, and he carried the older man's conviction that everything glittery is bullshit. Longtime Pulp violinist Russell Senior did Cocker one better and left the band altogether. That perspective is all over This Is Hardcore. It's a true curiosity: a band with a budget and an audience and a sense of reach making its definitive statement of emptiness and negation.

Cocker was (and is) a funny motherfucker, which added a whole new dimension to the album. "Help The Aged" is a bleak, extended riff about how your grandparents were once horny degenerate kids just like you, and how you are doomed to become just like them if you even live that long. "Dishes" is the song where Cocker forcibly abdicates his voice-of-a-generation role, though it also has some of his best wordplay: "I am not Jesus, though I have the same initials / I'm just the man who stays home and does the dishes." "A Little Soul" is a rare triple-pun. It's the Pulp song that sounds most like Smoky Robinson, for one thing. It's written as an address to a child -- a little soul. And it's all about how Cocker is terrified that his kid will turn out to be like him: "I look like a big man, but I've only got a little soul / Wish I could show a little soul."

This Is Hardcore's title track is like an elegant, sprawling, very British take on Weezer's "Tired Of Sex." When the album came out, Cocker would talk in interviews about watching porn in hotel rooms, but it also sounds like he's talking about sex, reducing it to absolute tedium: "Oh, that goes in there / And that goes in there / And that goes in there / Oooh, and then it's over." And that same fatalism extends outside of personal relationships, into grander narratives. "Glory Days" might be the one moment on the album where Cocker willingly adapts the whole generational-voice thing, and it's simply to tell us that everything sucks: "Oh, we were brought up on the space race / Now they expect us to clean toilets / When you've seen how big the world is / How can you make do with this?" With some minor adjustments, a millennial could've written that exact same line, and it would be just as cutting and true now.

Still, for all its darkness, This Is Hardcore is an uncommonly gorgeous album. The band never turned "TV Movie" into a single, but it's a perfect song, a tender and elegant lament from a dumped man. It might be the most soulful, controlled, masterful vocal performance in Cocker's entire career, and the climactic moment -- "why pretend any llllllooooooonnnngaaaaa" -- is one of things I wish I could inject directly into my cerebral cortex. Between April 1998 and whenever I stopped being able to buy cassette tapes in Rite-Aid, I put "TV Movie" on pretty much every mixtape I made. (I made a lot of them, too. Never adapted to the CD burner era.)

"TV Movie" is, for me at least, the album's greatest moment, and probably the greatest moment in Pulp's career in general. But you'll find that kind of transcendent beauty all over This Is Hardcore. "A Little Soul" flutters and tingles. "Dishes" has a sweetly assured lope to it. "I'm A Man" has a tiny bit of glam-rock strut, but it's soft and considered. Even the endless synth-drone that ends album closer "The Day After The Revolution" is pretty enough that I rarely cut it off early. The album's production is warm and pillowy and inviting. Usually, when bands make knowing and conscious career-suicide albums, they do it by either making everything into a noisy, discordant scrape or by throwing in 15 different genre left-turns per song. Pulp did it by making the most outright gorgeous album of their career. It was all in the attitude.

And that beauty, more than the perfectly rendered darkness, is what's kept me coming back to This Is Hardcore for the last 20 years, why I still rank it as the best Pulp album. This Is Hardcore wasn't especially influential, and it didn't sum up a moment in time. But it's a stark and complete and beautifully realized personal statement. It's the deepest, heaviest distillation of a remarkably deep and heavy band's worldview. Two decades after it first confused me, I still get lost in its perversity.