Music fans can often be territorial. "That's an understatement, my friend!" Michael Imperioli -- the actor/writer/director best-known for his role as The Sopranos' perennial fuckup Christopher Moltisanti -- cackles over the phone when I make this statement to him in conversation. And the sentiment is extremely relevant to him right now: His just-released debut novel, The Perfume Burned His Eyes, features late rock legend Lou Reed as a central figure, detailing feedback-drenched apartment recording sessions and late-night drug benders through the eyes of the book's protagonist, 16-year-old teenager Matthew.

Even though Reed looms large throughout -- the novel even takes its title from Reed's "Romeo Had Juliette," from his 1989 solo album New York -- the book is much less about him and more about Matthew's own journey through adolescence in the seedier corners of 1970s New York. Regardless, when various music publications ran items about the book's upcoming release, the novel's true intentions got somewhat lost in translation. "[A.V. Club] wrote something about how 'Michael Imperioli wrote a book where he gets to be best friends with Lou Reed,'" Imperioli good-naturedly observes. "I don't think they read the book, but they put that in there assuming I'm writing about me, which I'm not. Pitchfork said something like, 'Michael Imperioli wrote a book that sounds like Lou Reed fan fiction,' which maybe it is. It's fiction, and I'm a fan. But it's not about me, and it's not a Lou Reed book."

The truth is that Imperioli never really set out to include Reed -- who was an acquaintance of his over the past two decades -- as a character in his book. "My son was 16 in 2013, and he was going through normal things most 16-year-old kids go through," he states, citing Catcher In The Rye as a formative literary influence. "I was trying to relate to a 16-year-old state of mind, so I started writing this coming-of-age story set in a period of New York I'm interested in -- 1976." A few months into writing, Reed passed away, which "hit me on a few different levels," he admits. "Those two things came together, and this book was a result of that."

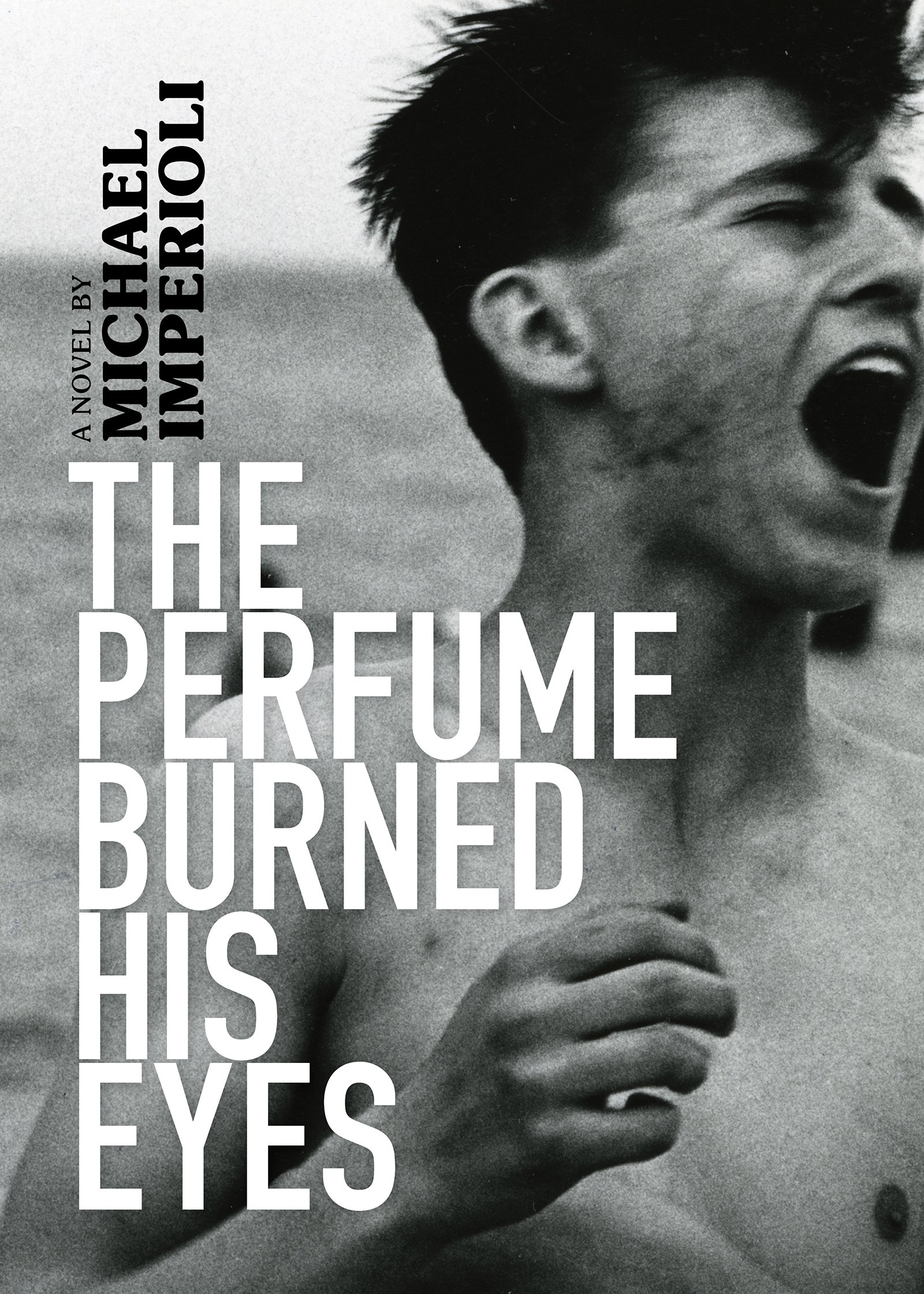

A die-hard music fan, Imperioli mentions Reed and Morrissey ("Steven P. Morrissey," specifically) in The Perfume Burned His Eyes' acknowledgements; "I wanted the [book jacket] to look like a Smiths album cover," he says about the evocative image that adorns the front cover. Lately, he's been listening to a lot of Galaxie 500 and Mark Mulcahy, as well as T. Rex. He's the type that could probably talk about his favorite records for hours -- but he's a busy guy too, so read on for an edited and condensed version of our conversation about meeting Lou Reed, figuring out how to portray the legendarily intimidating figure in literary form, and what he thought of Lulu (really).

STEREOGUM: How did you decide on the details of your portrayal of Reed?

IMPERIOLI: It was a combination of a couple of things. I did research. I had known a lot of things about him because I am a fan -- I've read a lot about him over the years. But none of the events in the book are true. Around 1976, he did in fact live with a transgendered girlfriend -- which I didn't find particularly strange or out there, considering his music and what he wrote about. But what I did find strange is that he moved to the Upper East Side to a posh park building. [Laughs] I thought that was really weird. It was such a strange neighborhood for him to live in, especially during this period in which he was pretty out there on drugs, from what I'd heard.

I wanted him to represent a certain level of madness and chaos, but in an artistic way. To me, he represents the artist -- a shaman, almost. That madness was important to the story, but the other side of artists I admire is sensitivity and compassion. I witnessed those sides first-hand -- not the madness or the drugs, but the generous, kind side. He was all those things to me. This particular period of his life was before he slayed a lot of demons that he wound up slaying later on. I wanted him to be a quasi-father figure to this kid, because on one level it's a strict coming-of-age story about a kid who loses his male role models and is almost adopted by this father figure, but it's also about the circle of artistic influence -- Lou influencing this kid artistically.

STEREOGUM: When was the first time you met Lou?

IMPERIOLI: The first time I met him was around 1994. I was at a Knicks game and I saw him on the escalator. I was shooting I Shot Andy Warhol at the time, which I'd heard he was really pissed off about because this woman shot his dear friend. I was a big fan, but I don't think he knew who I was -- not a lot of people did -- and I said, "Hi Lou, I'm a big fan. I know you're not happy about it, but I'm doing this movie and I'm playing [late actor and Warhol associate] Ondine." Lou looked at me and said, "Good luck," and turned away. He looked back at me over his shoulder once or twice, and then walked back over to me and said, "Listen, do your thing, do your work, have a good time. Just remember, Ondine was very, very funny." Then he walked away.

I'd see him once in a while walking around the Village when we both lived there in the 90s. After The Sopranos hit, he was doing a concert in New York, and I asked my manager if I could get tickets because it was sold out. She went through his publicist and my wife and I went. The show was incredible -- Ecstasy just came out, which is a great record, and his performance was amazing. After the show, his publicist said, "Lou wants to meet you." I didn't know he even knew who I was or that I was there. He was incredible -- really warm and sweet.

From then on, we saw each other a bunch of times. We were involved in charities together, like the Jazz Foundation of America and the Tibet Fund. I spent an afternoon with him in the studio when he was rehearsing for a show. I treasure all those moments.

STEREOGUM: What did you think of Lulu?

IMPERIOLI: [Laughs] I loved it. [Laughs again] I loved what he did. One of the things I was blown away from was his ability to be creative through his whole life. He was still experimenting and trying things, willing to go out on a limb and do something his fans won't like. He never became what a lot of rock legends become: a nostalgia act. He'd play old stuff, but with whatever edge he wanted to work out at the time. He was always making new forms of music, until the end. Not a lot of people have been able to do that, especially on the level that he did.

STEREOGUM: There's a moment in the book where a character tells Matthew that he's never heard of Lou Reed. It's pretty easy to forget that he was a largely unknown cult figure during the '60s and '70s.

IMPERIOLI: Oh yeah, he was an underground thing. "Walk On The Wild Side" was a hit, but a lot of people back then wouldn't have been able to name another song of his.

STEREOGUM: Do you remember the first time you became aware of Lou Reed?

IMPERIOLI: In high school, a girl had a T-shirt [with Reed on it]. I asked her who that was -- I didn't know at the time. She turned me on to Transformer, which blew my mind. That was the first one I heard -- I didn't listen to the Velvet Underground until later.

STEREOGUM: The book's scope includes Lou Reed's death. Where were you when you found out he passed?

IMPERIOLI: I was home. A friend called me. I heard over the summer that he was getting really sick and had a liver transplant. I hadn't seen him in a while and wrote him in August to wish him a speedy recovery. He wrote back, and that was the last I heard from him -- two months before he died. I still have it on my wall, it says "I'm happy to hear from you. I hope our paths cross again soon." It touches me every time I look at it.

STEREOGUM: Lou Reed was never someone who was shy about expressing his opinions. What do you think he would think about this book? Would you even want him to read it?

IMPERIOLI: [Laughs] I wouldn't have written it if he was alive -- I'll admit that much. There's a lot of liberty taken. As an artist, he really wanted to bring a literary sensibility to rock and roll, and he did that -- par excellence, better than anybody had. Maybe in some respect, whatever he did with rock and roll that touched me I can bring to something literary, in reverse, almost. I would hope he would read it as a tribute and homage with the utmost admiration, love, and respect.

STEREOGUM: Has your son read the book yet?

IMPERIOLI: Yeah, all my kids have read it -- I think they really liked it. I didn't write it for kids, per se, but a lot of people who have read it have said it might be a good book for teenagers and young adults. It gets dark and heavy, but as we've seen in the last couple of weeks, teenagers are dealing with a lot of heavy stuff in the world right now.

STEREOGUM: Obviously, being a teenager in 1970s New York City is a lot different from being a teenager right now. As a father, how have you seen teenage experiences in America change over the years?

IMPERIOLI: When I was young, you went to school, dealt with your friends and drama, went home, did your homework, went to bed, and started over the next day. But that social interaction that happens at school doesn't end now -- it goes until the minute you go to bed, and starts again when you wake up. That, more than anything else, causes a lot of pressure on kids.

My 20-year-old, when he was in high school, told me his biggest fear was being shot -- and he didn't go to an inner-city school with metal detectors. It was a mellow school. But the fear of some kid bringing in a weapon into school, going nuts and killing people -- they live with that. I have a lot of hope for this generation because they're taking the responsibility into their own hands, which they should be doing. People better start listening.

//

The Perfume Burned His Eyes is out now via Akashic.