It's late 1997 or maybe early 1998, and the grainy VHS video shows six of the most exciting young rappers in the greater New York area sitting around the same table. In the years that would follow, some of them would become legends, and some would become cautionary tales. Some would become both. One would achieve generational megastardom and then flame out hard. One would inspire a whole underground renaissance before going into a self-imposed African exile. One would try to join the Army and would then be discharged for smoking weed a couple of years later. One would just kind of fade away. One would spend seven years in prison, convicted of trying to smuggle a briefcase full of liquid cocaine through Newark International Airport, before being pardoned by George W. Bush. And one would die. The best pure rapper among them would die.

In the video, they're all supposed to be freestyling, but only Mic Geronimo really does. The rest of them are spitting verses from songs that haven't come out yet. They're all supposed to go around in a clockwise circle, taking turns, but they don't do that, either. After Mos Def raps his "Re:Definition" verse, Canibus politely declines to go next: "I'm not tryna play niggas, but yo: I deserve the right to anchor y'all. I deserve the right." If Canibus hand't pulled that, then Big Pun, his tremendous bulk already dwarfing the whole table, would've gone last. And when Pun raps, he proves why he should've gone last.

Pun raps what would end up being the first verse from "The Dream Shatterer," and people lose their minds. These are rappers, mind. They might be friendly with one another, but they also know that they're in competition with one another. They try to no-sell each other's punchlines. But you just can't no-sell Big Pun's punchlines. "I'm carving my initials in your forehead / So every night before bed, you see the BP shine off the boardhead." Big reaction. "Hit him with a thousand pounds of pressure per slap / Make his whole body jerk back / Watch the earth crack, hand him his purse back." Someone laughs from sheer delight. "A man of honor wouldn't try to match my persona / Sometimes, rhyming, I blow my own mind like Nirvana." People's heads are spinning now. "Head to head in the street, I'll leave your dead on your feet / Settling beef, I'll even let you rhyme to the 'Benjamins' beat." DMX is just kind of making sounds.

By the time he finishes, DMX is screaming: "Punisher! Punisher! Run his verse back!" The camera, whirling around, catches Irv Gotti, looking like he just got off a rollercoaster. Canibus, grinning despite himself, knows exactly what just happened: "You wanted that anchor bad, huh?" And when he does his LL Cool J dis "2nd Round K.O.," one of the most devastating songs of its era, it feels like a total anticlimax.

Pun was a monster. We didn't have him for long, but what he left behind remains dazzling, forbidding, almost impossible, like Ernest Hemingway stripping the English language down to its component parts while drinking himself into oblivion. Consider what might well be the most thrilling two-bar run in the entire history of rap music: "Dead in the middle of Little Italy / Little did we know that we riddled two middlemen who didn't do diddly." With a few brief seconds of track, Pun paints a whole tableau of underworld war, of tragic mistakes, of total disregard for human life, and he does it with dazzling speed and impeccable technique, cramming in endless internal rhymes without sacrificing meter or meaning.

Pun came up in an era of abundance, entering into a post-Biggie New York rap landscape that was full of hungry young larger-than-life annihilators. And yet whenever he showed up on songs with his peers, he always seemed to elbow them out of the way, to reduce them. Listen to Pun on "Off The Books," on "Banned From TV," on "John Blaze," and you will hear a titan among titans. He could do things. His voice, in itself, was nothing too special -- a hard and affectless rasp, not terribly expressive, with a bit of Puerto Rican Bronx honk in it. But he used it with clinical force. His breath control was ridiculous, his imagery distinct and vivid, his imagination -- at least within the boundaries of the crime-rap context that helped defined him -- just about boundless. He was hard and funny and technically absurd. He was a magician.

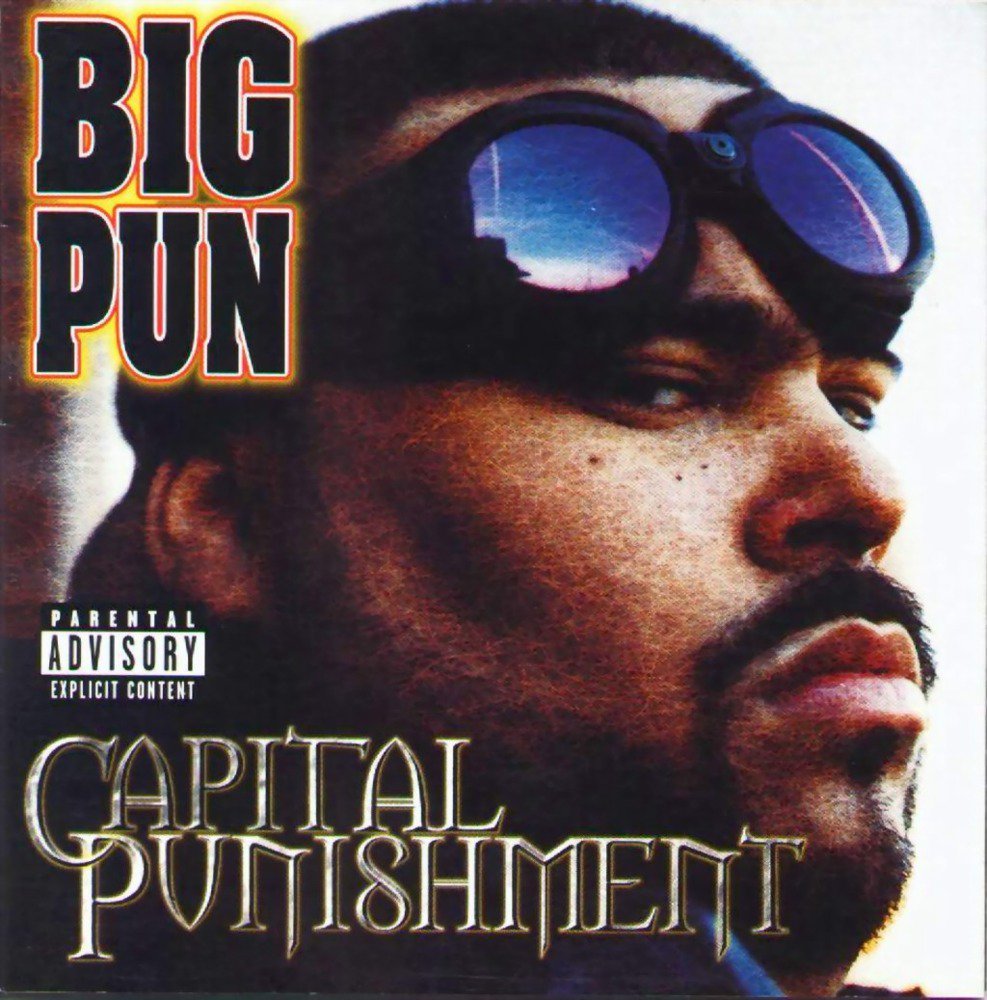

On Capital Punishment, the only album that Pun managed to release during his lifetime, Pun tested himself. He went head-to-head against some of the greatest pure rappers of the time -- against Black Thought, against Prodigy, against Inspectah Deck. He didn't just hold his own against those guys; he overwhelmed them. And he did it while making songs. That's almost always a problem for pure-rap virtuosos. It was a problem for plenty of the guys who sat around that table with him. (Canibus was almost hilariously bad at it. That guy tried to launch a much-hyped debut album with a single where he rapped from the perspective of a sperm.) It wasn't a problem with Pun.

Pun's widow has said that she was surprised when he started rapping. He loved R&B and the Bee Gees and Phil Collins. He sang all the time. And you can hear that side of Pun on Capital Punishment. He had a hell of an ear. He knew how to handle horns and high-stepping drums and grand, funky basslines. He knew how to floss, how to deliver punchlines so that they landed like hooks. There wasn't just clinical intensity in his voice; there was joy, too. He loved the novelty of being the enormously fat guy who would talk about being a tireless loverman, and he sold that image. He made "Still Not A Player" into a top-five pop hit.

Capital Punishment was a product of its time. Pun does an obligatory sensitive story-song or two, and they work, but they don't work as well as the moments where he's just rapping as hard as he can. There are skits, and some of them are both absolutely disgusting and genuinely funny. (A humiliating rite of passage for rap dorks of that era was having someone walk into the room while that skit where the two girls are fighting over who will get to fuck Pun is playing.) There's homophobia, and gross sex-talk, and a not-very-good Wyclef verse. It's a time capsule, but it's also a monument to a singular talent, the likes of which we won't see again.

Pun had serious, severe problems. He'd come out of an abusive childhood and an adolescence spent in New York's drug trade. And he repeated the patterns he'd learned. He was a horribly abusive husband and father. He once pistol-whipped his wife on camera. He also ate compulsively, as a coping mechanism. He tried to lose weight, but he never tried hard. Two years after the release of Capital Punishment, he was dead of a heart attack at the age of 28. When he died, he was just a hair under 700 pounds. If he'd survived, maybe he would've gotten his life together and become a respected public figure, the way Jay-Z has done. It's more likely, I think, that he would've gone to prison, or that his behavior would've turned him into a public pariah. He did bad things, and he didn't take care of himself. But good lord, he could rap.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=hA1UqfMBrKg