"This is the half-light, see me as I am."

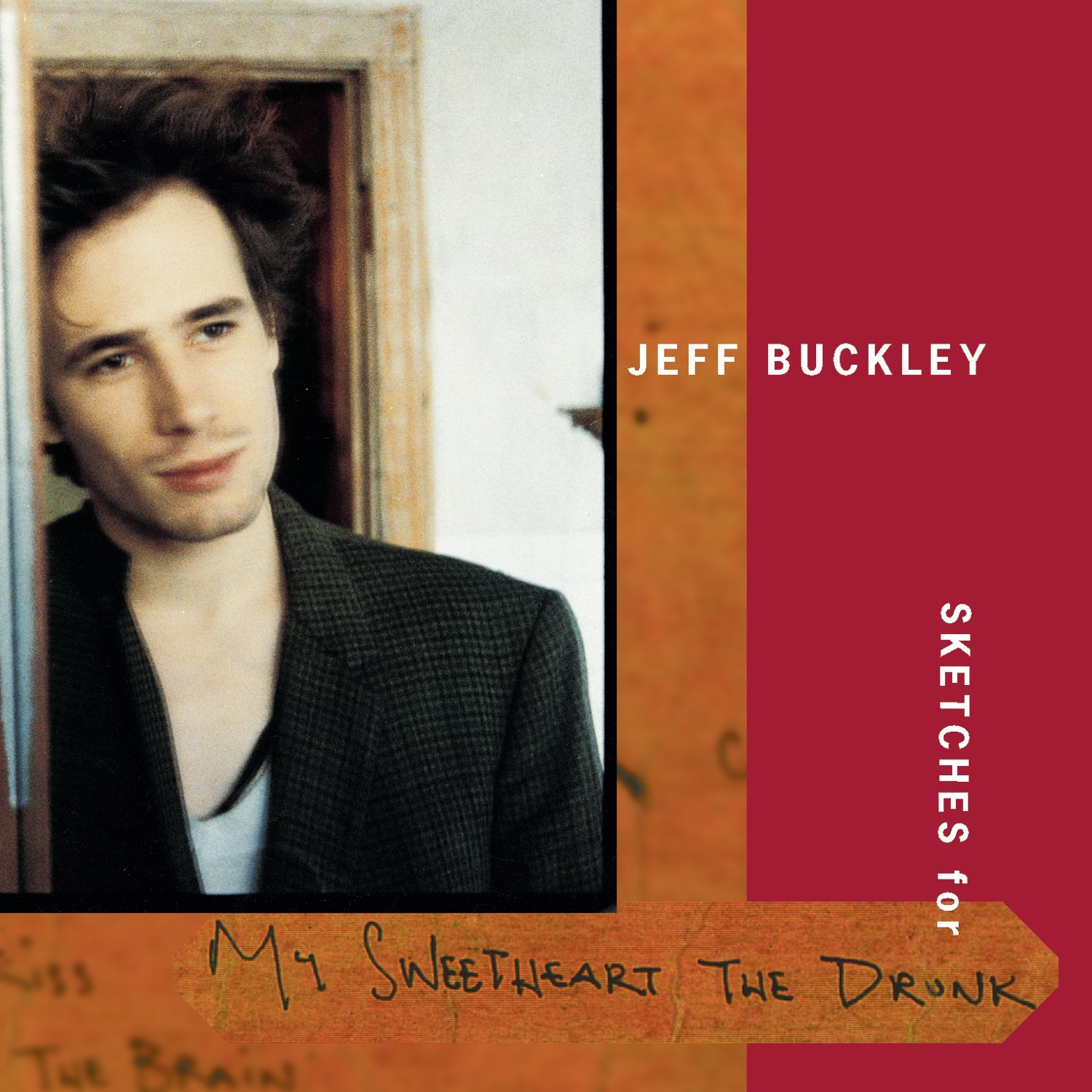

When Jeff Buckley wrote that line in 1997 for a love song called "Opened Once," he may simply have been referring to the eerie, revealing qualities of dawn and dusk, which have fascinated writers throughout history. But 20 years after the song's release on Sketches For My Sweetheart The Drunk, it's easy to envision his first posthumous compilation as its own kind of revelatory half-light. Its first disc is culled from sessions produced by Television's Tom Verlaine, with which Buckley was unsatisfied; its second from rough four-track demos Buckley recorded by himself, new songs he was itching to record with his band at the time of his death. Capturing a fleeting overlap between the complete-but-frustrating and the incomplete-but-exciting, Sketches casts Buckley in dramatic relief. Though unpolished, the album lays bare the full scope of Buckley's personality and artistry more so than any other musical document he gave us in his tragically brief 30 years of life.

(Note: David Browne's book Dream Brother, which exhaustively chronicles Jeff and his father Tim's lives, is widely considered the most in-depth non-musical Buckley document, and is the source of all quotes used in this piece.)

Buckley spent the better part of three years, from mid-1993 to mid-1996, writing, recording, promoting, and touring Grace, his masterful debut album. He returned home exhausted and burdened by debts owed to his label, Columbia, for the massive expenses incurred by the Grace release cycle. Feeling the pressure -- but perhaps not the inspiration -- to record a follow-up, Buckley and his band embarked on a series of false starts, starting with a month spent aimlessly jamming in a house in Sag Harbor, Long Island. Columbia A&R Steve Berkowitz, who was instrumental in signing Buckley, visited the house a few weeks into the band's stay and noted that their initial demos were aimless 20-minute rambles that "sounded like a constant loop." "Uh, buddy," he prompted Jeff over breakfast the next day, "What's goin' on?"

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Despite the huge deal he'd gotten from a major label a few years prior, Buckley had plenty of reasons to be disenchanted with the music industry and unmotivated to churn out Radio Friendly Unit Shifters, to borrow a phrase from one of his contemporaries. Before he was even born, his father walked out on his pregnant mother in favor of a music career, and throughout his life, Jeff associated the industry with his abandonment issues. He was also wary of being known simply as Tim Buckley's son. "I'm convinced part of the reason I got signed is because of who I am, and it makes me sad," he wrote in his diary in 1993, "But I can't do anything else." If you've ever heard Jeff Buckley sing or play guitar, you'll recognize how paranoid he must have been to harbor such a fear of inadequacy.

Around the time Buckley started writing songs for his second album, which he'd tentatively titled My Sweetheart The Drunk, his aversion to all things commercially friendly seemed to take on a directly inverse relationship to Columbia's concerted efforts to make him a star. He had already shown his reluctance towards crowd-pleasing during the Grace sessions -- his label called a dinner meeting in an attempt to resuscitate a song with hit potential called "Forget Her," and Buckley first rebuffed them with a gentle, "It's not ready," and when they persisted, he told the three Columbia and Sony executives, "If I hear the song again, I'm going to throw up." By the time My Sweetheart was in the works, both parties became even more entrenched in their positions.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Buckley had largely ignored punk and indie rock in favor of fusion and classic rock for most of his life, but partially because of his budding relationship with Joan Wasser (better known today as Joan As Police Woman), he became infatuated with scuzzy, DIY-minded bands like Flipper, Polvo, and the Jesus Lizard in the mid-'90s. He ingratiated himself with New York's downtown punk scene, befriending Nymphs singer Inger Lorre and crucifying Grace in front of her by describing it as, "Kinda corny. It's like love songs. You wouldn't like it."

Columbia initially liked Buckley because, with his frequent covers of Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, and other classic artists, he presented a more canon-reverent alternative to his contemporaries in grunge. However, the label seemed to abandon this mentality upon realization that My Sweetheart… had to be a commercial smash in order to recoup the money spent recording and promoting Grace. After tapping Andy Wallace, whose production experience was mostly in metal, for Buckley's debut, they decided that the follow-up would need someone with more chart experience, and pitched Buckley on Butch Vig (Nevermind, Siamese Dream), Brendan O'Brien (Ten, Plush), and Steve Lillywhite (Achtung Baby, Crash). Buckley bristled, telling a friend, "They want me to be Dave Matthews."

This conflict wore heavy on Buckley, who attempted to exorcise it on Sketches… cut "Murder Suicide Meteor Slave":

Not a trampoline of the freaks/Not even a slave to your father/You're a slave to it all now

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

A certain amount of restlessness had always defined Buckley. In the years before he began performing as a solo act, his resumé was eclectic to say the least. He played in jazz and metal bands in high school, became infatuated with fusion while studying at LA's Musicians Institute in the mid-'80s, and shortly thereafter played in the AKB Band (reggae), Wild Blue Yonder (roots rock) and Group Therapy (metal). He logged time as a session musician for R&B artists. He backed up dancehall artist Shinehead on tour. He unsuccessfully auditioned to play with NYC hardcore legends Agnostic Front as well as former Prince bandmates Wendy & Lisa. In his book, Browne noted Buckley's "ability to expertly copy any genre he desired" and observed of his early New York shows, "Watching him perform was akin to observing a rabid music fan rifle through a record collection and play treasured songs."

Part of the reason Grace holds up so well is its effortless blend of genres -- the wistful rock balladry on "Last Goodbye" and "Lover, You Should've Come Over," the entrancingly spare covers of "Hallelujah" and "Lilac Wine," the mystical hard rock of the title track and "Eternal Life." "From the beginning, we understood the album would have a wide variety on it," said Wallace, "It wouldn't be a one-sound album." Despite that, Buckley the polyglot made everything his own, throwing his long list of seemingly incongruous influences into a trash compactor and somehow emerging with an expertly cut diamond.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Grace's potpourri seems organic, and that belies how many years Buckley put into its songs and how much work was necessary to ensure it was released on the right label, with the right band, and the right producer. But the runway for Buckley's debut album was a silken postage stamp compared to the winding gravel road he travelled while trying to bring My Sweetheart the Drunk to fruition.

Much to Columbia's chagrin, Buckley became set on working with Tom Verlaine, a cult post-punk hero whose production experience was then limited to his own albums. Verlaine was anything but the obvious choice, both for his lack of experience and his allegedly prickly nature, but after Buckley met him at a Patti Smith recording session and started rattling off obscure chords from Television's classic Marquee Moon, the two men clicked. Columbia wanted so badly to believe that this was just another one of Buckley's phases that they oxymoronically labelled the tapes from his and Verlaine's first sessions as "demo masters."

Verlaine and Buckley may have had chemistry, but that didn't help the fact that the latter still had no idea what he wanted his sophomore album to sound like. "You had to kind of guess to find the direction zone for the tunes, and he wasn't real forthcoming about it," Verlaine said of the inaugural My Sweetheart sessions. Buckley had always been a procrastinator who thrived under pressure, the type to arrive at the midnight conclusion of vocal overdubbing session without finished lyrics, ask the engineer, "How about if I meet you back here at two A.M.?", and return to complete the song in a couple of takes (as was the case with Grace's "Dream Brother"). Something about My Sweetheart drew out his indecisiveness and stumped his eleventh-hour creativity.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

In his younger years, Buckley seemed content flying by the seat of his pants, but it was starting to catch up with him. "I prepared my entire life to face the future unprepared to face the future. I hope I explode from the lesson," he wrote in his diary in 1996. As evidenced by the time he took a two-day break from working on Grace in the wake of a review that unfavorably grouped his debut EP with Michael Bolton's latest release, Buckley had always had a fragile side, and My Sweetheart's prolonged gestation also exacerbated that.

By 1997, the Grace follow-up was, in Browne's words, "starting to feel like an endless round of jams, fruitless recording sessions, problems with band members, and instruments being hauled from one subterranean practice room to another back in New York." Buckley decided a change of scenery was in order and decamped to Memphis for a second try at recording with Verlaine and his band. For whatever reason, Buckley emerged unsatisfied with these sessions as well. He sent his band home, tried some more solo recording with Verlaine, and then dismissed his producer.

Buckley remained in Memphis for the last months of his life, renting a modest shotgun house, performing at a local bar, and recording demos of new songs over Willie Nelson and Michael Bolton cassettes he bought from a street vendor (the hilarious irony of the latter was not lost on him). In the weeks before his death, he was in contact with his bandmates and label bosses in New York, telling them of his plans to record half of the new songs with his band and half with his friends in Memphis indie band the Grifters and nab either Wallace or Sub Pop/K Records mainstay Steve Fisk as a producer. Buckley's drummer even said that in one phone conversation, Buckley told the band that he wanted to burn the tapes from the Verlaine-led sessions upon completion of his new vision for My Sweetheart The Drunk.

Of course, none of this happened. In a tragedy nothing short of Shakespearean in design, Buckley's band landed back in Memphis at almost the exact moment that he was swallowed up by the Mississippi River on the night of May 29, 1997. The latest version of My Sweetheart The Drunk that Buckley had spent months dreaming up would never exist.

Instead, we've had 20 years to ponder over Sketches For My Sweetheart The Drunk, a compilation organized by Buckley's mother and his various contacts at Columbia. It was released a year after Buckley's death, almost to the day, and received reviews that were mostly positive despite most noting that Grace was superior.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Grace is superior, there's almost no question about that. During his brief solo career, Buckley showed that he alone had the best idea of what Jeff Buckley should sound like, and so any album for which he lacked final cut privilege suffers accordingly. The songs on Sketches are alternately subpar or rough, the lyrics aren't always up to snuff, and as was decidedly not the case with Grace's alchemical infusion of Buckley's widely varied influences, the eclecticism is impossible to ignore.

And yet, Sketches still has something on Grace: it allows an unparalleled window into the the world of one of the most naturally gifted musicians of the last 30 years. Grace, as its artwork suggests, is the glamor shot. Sketches is #nofilter. Sketches grants the same level of access as The Beach Boys' Smile compilations, the multiple cuts of Blade Runner, or the making-of documentary about Alejandro Jodorowsky's failed film adaptation of Dune -- when all you're given is pristine final products, actual genius sometimes looks too easy.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

In covering twice as much stylistic ground as Buckley's debut with half of its finesse, the posthumous compilation reveals compartmentalized versions of subsequent paths he could've taken. Opener "The Sky Is A Landfill" is, despite its overzealous lyrics about pollution and TV mind control, pitch-perfect stadium rock, one that foamed up Steve Berkowitz's mouth to the degree that he declared it "the next chapter of U2." The very next song, "Everybody Here Wants You," could be slotted on a neo-soul compilation next to contemporary performers like Maxwell and Erykah Badu and no one would bat an eyelash.

The alternate universe Buckleys abound as the album continues. The dark "Nightmares By The Sea" is post-punk poetry; "Yard Of Blonde Girls" is Marc Bolan strutting all over the grunge era; "Witches' Rave" is Buckley fronting the Pretenders; "New Year's Prayer" is at last a materialization of Buckley's longtime love for Qawwali, the acrobatic vocal music performed by Sufis for hundreds of years.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The much rawer, weirder second disc presents an entirely different set of Buckleys, most of which cast him in a DIY (or even outsider art) role that he never came close to in his actual life. Most startling of all is the aforementioned "Murder Suicide Meteor Slave," a hair-raising symphony of overlapping guitar and vocal tracks (psych-rock guru Dave Fridmann has probably had multiple wet dreams about turning it into the full-on freak-out it deserves to be). Even the suits liked this weird shit. Berkowitz said, "The four-tracks were the greatest stuff he ever did. He was on the verge of making a major record, like Sgt. Pepper."

At its core, Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk is two things. It's a stark documentary on Buckley's inner turmoil, his fidgety character, and his trials and errors on the path to a sophomore album. You can hear him trying to gain punk cred, trying to purposefully avoid hits, trying to pay homage to his musical heroes, and not quite getting there. On one hand, the album portrays Buckley more accurately than any streamlined biopic ever could. But Sketches is also a work of science fiction. It allows glimpses of the many paths Buckley could've pursued had he lived, and suggests that whichever one he chose to follow would've produced music that puts any existing posthumous compilation to shame. Knowing how he worked, it's easy to imagine Buckley coming up with a last-minute lyrical tune-up of "Landfill" or a "Witches' Rave" melody that transformed it into a hit. Sketches presents a one-in-a-lifetime talent in flux and allows for fans to extrapolate on their own. Jeff Buckley looked incredible in the spotlight, but in the half-light, you see him for what he really was: a restless dreamer whose prodigious skill and voracious taste tripped him up just as often as they elevated his craft.