Going into 1998, Billy Corgan was on top of the world. Three years earlier, the Smashing Pumpkins released their third official full-length, the ambitious double album Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness. Despite its eccentric title and daunting length, Mellon Collie boasted a handful of true crossover hits that helped it become a titanic success, eventually getting certified Diamond -- a rare feat that basically makes it the stuff of past-era fables in the context of today's music industry, even when accounting for its double album status. Between the album's prominence and the ensuing tour, the Smashing Pumpkins went from being one of the big alt-rock names of the era to true superstars. In the wake of that, Corgan could do whatever he wanted. And, well, he did.

That resulted in Adore, which the Pumpkins released 20 years ago this Saturday. The album was a demarcation. The divide in the Pumpkins story is often seen as the initial breakup -- there are the first five albums, and then everything that's happened since under various semi-reunited iterations. But in many ways, Adore is the real turning point. Before that, it was their steady ascension to being one of the foremost rock names of their time. Adore was in some ways a logical extension of and conclusion to the arc that had preceded it, but at the same time it was the implosion and crash landing. It reoriented the trajectory and set the Pumpkins on the path they've followed, through all its twists and turns, since.

Over the years, other alt-rock luminaries had dismissed the Smashing Pumpkins as careerist. Maybe that was true -- Corgan had a love of all things arena-sized from decades past, and his vision was always of the maximalist type intended to connect with many, many people. Mellon Collie isn't the sort of album that was playing to the market, though: It's gigantic, overflowing, and all over the place. But it bore such ingenious songwriting and earnest emotion that it somehow cohered, earning the attention and adoration of millions of people.

Corgan had already indulged by making it a double album, the sort of old world classic rock trope his peers would've found too gauche to even consider, let alone attempt. And he still had enough material left over from that time to soon unveil another 30 songs in the expanded singles collection/box set The Aeroplane Flies High, which quickly followed Mellon Collie in 1996. At that juncture in his career, the next Pumpkins album could've easily drawn from that same well. Corgan could have cherry-picked a few of those songs and, regardless of the threat of diminishing returns inherent in replicating a proven formula that probably shouldn't have worked in the first place, he would've been giving the people (and his label) what they wanted. More of the anthemic rock and cinematic balladry the Pumpkins had just perfected.

Instead, Adore falls into a long history of left-turn albums following a major mainstream success, a moment when an artist has enough clout to at least try to get away with whatever they desire. Sometimes, that turns into a post-fame freakout album, where an artist appears to retreat by willfully upending what recently garnered them so many new listeners; M83's Junk is a recent example in that mold. But Adore wasn't exactly a freakout -- not sonically, at least. Corgan was confident in his chosen direction. It's just that the direction was more personal, adult, insular. After the dizzying highs of the two masterpieces that preceded it, Adore was more of a post-fame comedown album.

The Smashing Pumpkins have never been a stable situation, but the circumstances that precipitated Adore were particularly fraught. The band was falling apart, having kicked drummer Jimmy Chamberlin out due to his heroin addiction. With his main musical foil and partner absent, Corgan felt unmoored. But his personal life was defined by struggles as well, the death of his mother and the collapse of his marriage both occurring during that period of time. Even if Corgan hadn't already harbored plans to move beyond writing music about the experience of youth, the adulthood crucible events he was experiencing would've forced his hand. There was no way Adore wouldn't wind up a more mature, reflective, pained collection.

But Corgan was also at a creative crossroads. Mellon Collie is the kind of album that can leave an artist no right path forward -- everyone's expecting a certain grandiosity from you now, but how can you go any bigger? And that's not even considering the dozens of other songs he wrote in the same era. They'd taken the Pumpkins to a logical end, from which there had to be some new horizon to chase. And he was simply burnt out, depleted of the type of riff-driven rock music for which people now knew and loved him.

Consequently, the lead-up to Adore alternatively positioned it as the Pumpkins' "acoustic album" or their "techno album." In the end, it was not exactly either of those things but sort of both -- without Chamberlin, Adore's songs often relied on drum machines or little percussive backing at all, and the songs were dominated by synthesizers, piano, and acoustic guitar rather than the raging distortion of past Pumpkins outings. There was potential in that, the fusion of the organic and artificial as well as the ancient and the futuristic.

But Adore was also very much playing into its moment. It was the late '90s, one of those eras where people were walking around proclaiming rock was dead thanks to the fact that electronica was taking over and would soon reign. Pop stars like Madonna got in on it, with her '98 release Ray Of Light; through '97 and '98, you had rock artists like U2 and David Bowie and R.E.M. also experimenting with electronic and dance music. The Pumpkins had already earned one of their biggest hits and best songs with the electronics-tinged "1979," so it only made sense that they'd engage with the new sounds of the era, too.

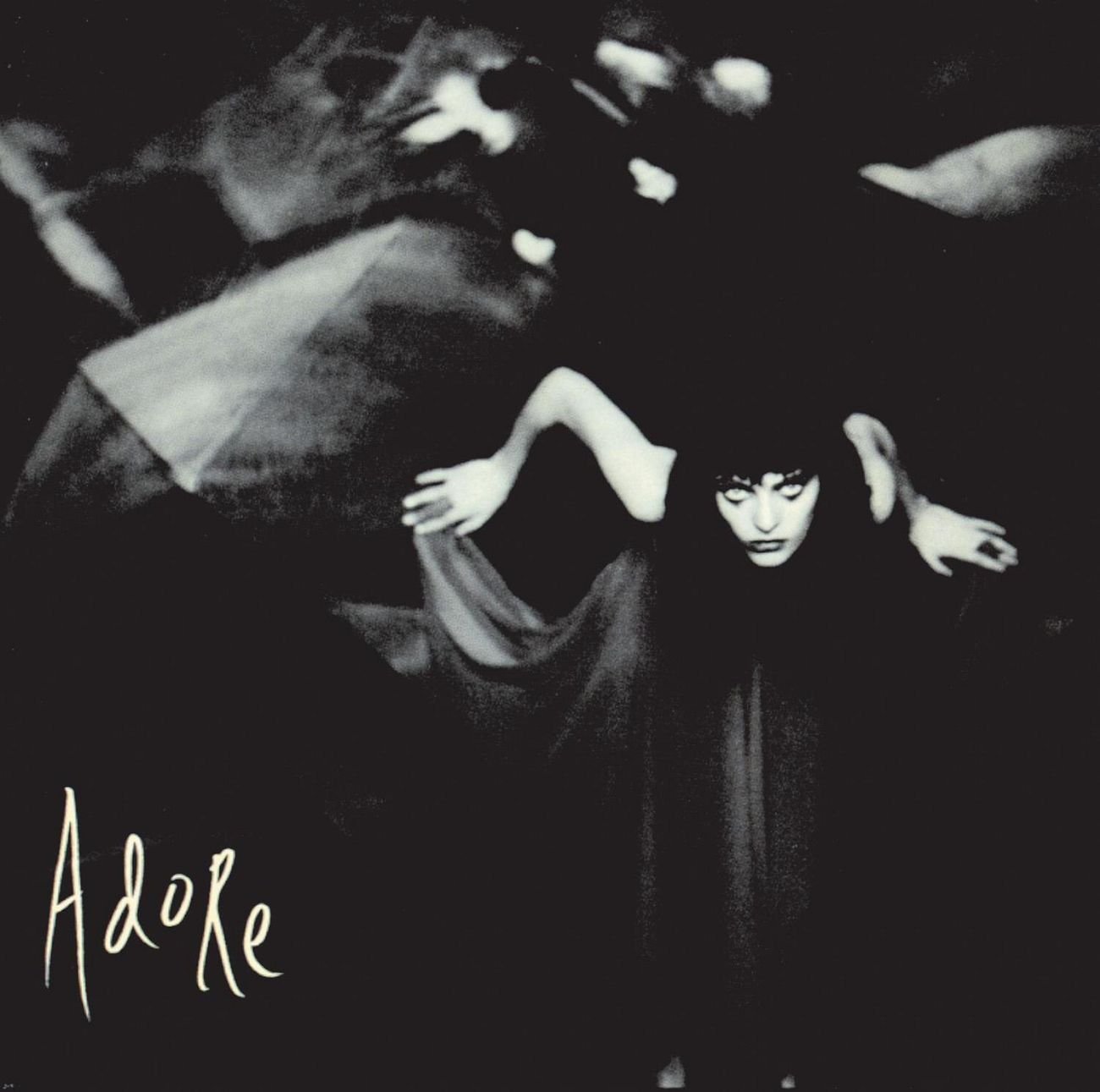

Ironically for Corgan, Adore was actually in some ways a return to his roots as well. Chamberlin's addition to the band was one of the factors that had first spurred Corgan to explore heavier music, thanks to the former's aggressive style. The drum machines and synths of Adore allowed him instead to echo the new wave fascination of his youth. In the context of 1998 and his headspace at the time, that mostly translated into a gothic-tinged aesthetic summed up by the album's cover, the Nosferatu vibes of the video for lead single and sorta-title-track "Ava Adore," and the autumnal gloom produced by the interaction between Adore's acoustics, mournful synths, and downcast melodies. Appropriately enough for an album that existed in the wake of multiple losses, the entirety of Adore sounds as if it happens in a solitary place, out in the woods on the precipice of winter just before the last leaves have fallen and all the color has nearly drained from the forest.

Twenty years later, all of this still divides fans. There are those that will argue that the backlash that faced Adore was, too, a product of the time. After all, the idea of a rock band using drum machines and synths was a more radical departure in 1998. And there are certainly some deeply affecting compositions on the album, a few that could rival Corgan's best work from the preceding years. But aside from the detractors who still just hate the idea of Corgan abandoning his penchant for guitar fireworks and cathartic refrains, there are some reasonable critiques to levy at Adore -- that it did negate some of the band's strengths, or that the songwriting simply wasn't as consistent as in the past.

There's an obvious parallel with another acclaimed, megalomaniacal '90s songwriter by the name of Noel Gallagher. Both he and Corgan had two or three masterpieces under their belts at a young age, albums that helped define their respective eras and cultures. Both worked at a furiously prolific rate during that time, and both experienced a late '90s turning point that began to alienate fans. The prevailing narratives for both Oasis and Smashing Pumpkins is that there was a steep drop-off after a couple albums, but diehards can still locate gems throughout the subsequent years.

Specifically in the case of Adore, all the business about techno and about Chamberlin leaving does obscure an album that is, mostly, accomplished. It isn't as exhilarating nor as lovable as Siamese Dream or Mellon Collie, but it feels like an album its creator needed to make. That can make for a rewarding listen all these years later.

Adore begins particularly strongly. After the fragile overture of "To Sheila," the album bursts to life with the throb of "Ava Adore." That track kicks off a run of darkened pop songs, from its own cacophony yielding one of those healing Smashing Pumpkins choruses that veer from coo to growl, to the sighing rush of "Perfect" right afterwards. "Daphne Descends" is proof that Corgan could indeed pull off synth-pop as well as he could do rock -- it's a gorgeous, haunting track driven by amber-hued synth drones. If the whole album had sounded like this, had been on this level, it may not have made much of a difference for the Pumpkins' fortunes in 1998, but it may have ensured that Adore would've been more forcefully reclaimed by history.

There are great moments spread out over the rest of the album. "Appels + Oranjes" makes a similarly convincing argument for Corgan's ability in electronic terrain. There's a rainy day wistfulness that hangs over that song and several others, like the dramatic current of "Tear" or the plaintive acoustic balladry of "Once Upon A Time," the latter of which could've fit in right alongside "Thirty-Tree" on Mellon Collie.

In the instance of Adore, Corgan's penchant for expansiveness is what still hurts the album years later, removed from its initial context. As Adore gets into its second half, the songs get less memorable, as if Corgan was able to wring tangible compositions out of the album's greyscale, impressionistic atmosphere at first but then wandered too far into it.

None of it is bad, exactly, there are just ways in which the album appears to lose focus and drag on. "Annie-Dog" might be broken-down on purpose, but it really just comes across as unfinished. And while "For Martha" often gets cited as a highlight, it's emblematic of Adore's final stretch, all drifting piano-based material that suggests a listlessness. Maybe there's some poetry to that -- the vaporous, ineffable destination of still looking for answers. But ending an album on a non-entity like "Blank Page" just feels unresolved from a writer as emphatic as Corgan.

Relative to today, Adore still did numbers -- just nothing compared to its predecessor. Even being certified Platinum wasn't enough to save it from being perceived as a failure, whether by underwhelmed fans or by the machinery surrounding Corgan. When I interviewed him ahead of Adore's 2014 reissue, he had some conflicted opinions. He called it their most important album, due to its total embrace of the muse without as much conscious concern for success. Alluding to the ways in which it was misunderstood, he asserted that there could be a timelessness to it thanks to that mixture of acoustic, folk-inspired material and forward-thinking electronic attempts.

That prompted him to argue that Adore would've made more sense in today's landscape than in 1998's. And at least part of him regretted the sharp left-turn maneuver he opted for at that time. "I basically ceded my position in the world," he said. "I surrendered my position in the world willingly without any real plan of how I was going to get back to it if I wanted to." That makes Adore a specific kind of post-breakthrough fallout: Corgan had every aspiration of being able to reach the stratosphere still, but he mishandled the situation. It wasn't an intentional retreat, but the story behind Adore and its new sound inherently gave it that comedown feeling. Sometimes that can result in a different kind of masterpiece. In the instance of Adore, it resulted in an imperfect yet strong album that, nevertheless, damaged the Pumpkins to the extent that they would never reclaim the level of prominence they held in the mid-'90s.

Who knows if there was really another way for their story to go -- not many of their peers enjoy the same stature they did in the mid-'90s, either. There was a big difference between 1995 and 1998; Mellon Collie 2 could've signaled creative stagnation more so than surefire continued success. And ultimately, as much as Adore does bear the marks of its year, there is indeed a way you could imagine it coming out today -- or, at least, an album with the same concept of blending folk and electronic, the past and the future, into a wearied yet heartfelt document of processing grief and loss.

Perhaps nothing was going to truly work after an opus like Mellon Collie, and perhaps that baggage still hangs over Adore 20 years later -- would that second half seem aimless at all if you could shake the idea that this was the deflated successor to one of the decade's mega-blockbuster albums? There are a couple ways in which Adore is flawed, but there are more ways in which it's special. Some albums are impossible to separate from their narrative, and they suffer because of it. Adore is still better than pretty much every Pumpkins release that came after. But in 1998, that wasn't quite enough. Two decades later, it's still hard to imagine it outside of that, to imagine if it had come out today, and if it had a chance to be taken solely on its own merits.