In 2005, Coldplay released their third album, X&Y. In many ways, it was one of those collections where a band starts to sound exactly like everyone's most basic idea of them. The subtle hints of something weirder that lingered at the edges of Parachutes and A Rush Of Blood To The Head, the element that allowed Coldplay to straddle the worlds of murky post-Britpop atmospheric rock and more straight-up mainstream pop, were mostly brushed away for their polished and often sappy third effort. There were still good moments -- "Speed Of Sound" was an endearing (and enduring) re-write of "Clocks"; the Kraftwerk-sampling "Talk" was addicting -- but material like the album’s huge hit "Fix You" gave their critics the exact ammunition they’d been looking for. Coldplay, so it went, were the poster-boys for a strain of lame, bloodless modern rock.

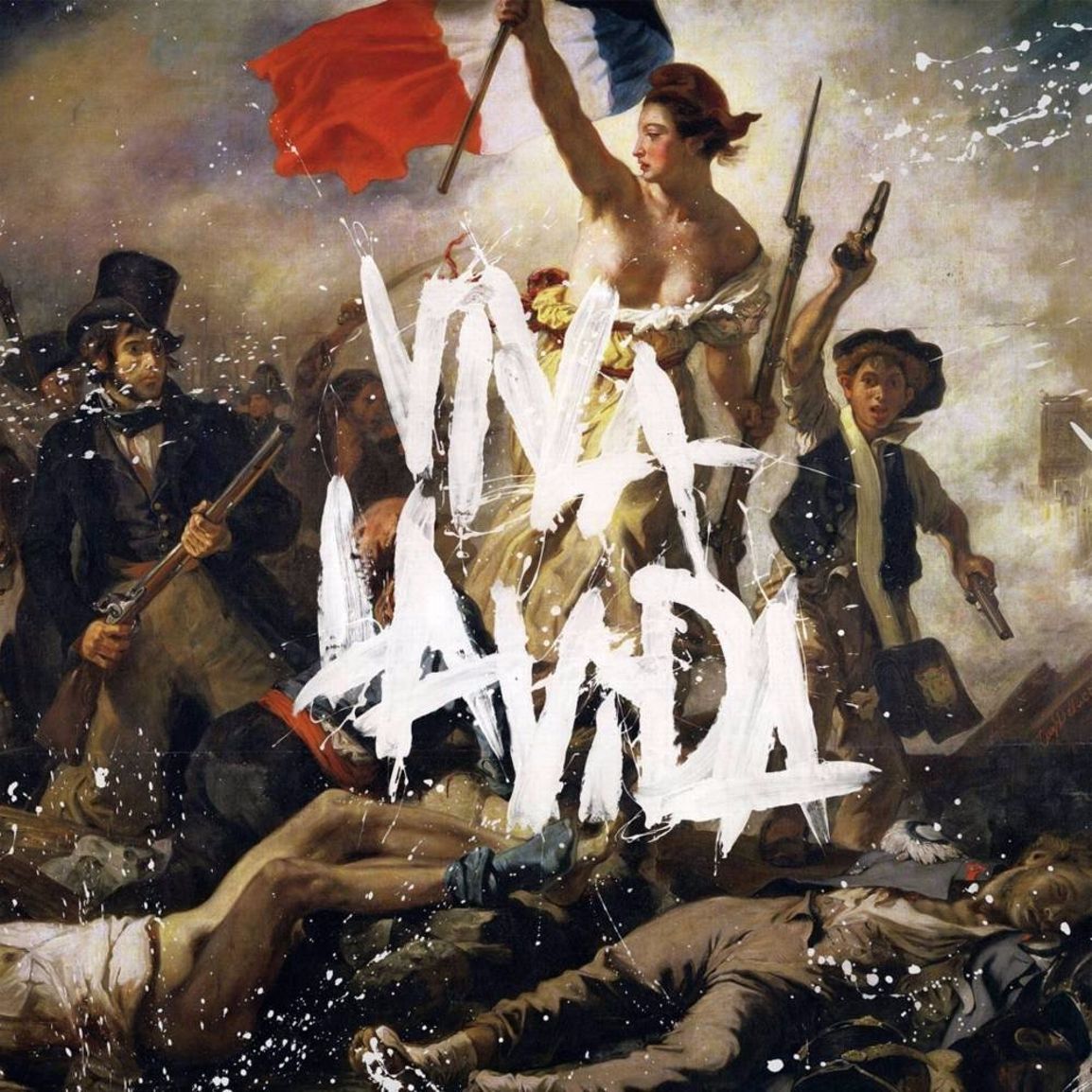

They had arrived at a crossroads. X&Y was still wildly successful, but even the band appeared to recognize that its bloated sheen had taken the original Coldplay template to its logical end point and, perhaps, a point of diminishing returns. It was time to change it up. So they enlisted Brian Eno, a producer whose legendary reputation partially rested in his ability to help an artist forge new textural and aesthetic backdrops for their work. The resulting album, Viva La Vida Or Death And All His Friends, arrived 10 years ago this Sunday.

As you might guess from its goofily long double moniker, Coldplay had arrived at the juncture in their career where it was time for the "difficult" and "weird" album. If you count their debut EPs, Coldplay had been releasing music for 10 years, and this was their fourth full-length. A left turn seemed appropriate right about then.

Naturally, just as they’d previously taken cues from Radiohead and U2 but mollified their forebears' more adventurous characteristics, so too was Viva La Vida a milder iteration of the lineage to which it belonged. Critics, of course, wouldn’t let that one go -- if this was to be Coldplay’s Kid A, surely they must reinvent themselves as severely as Radiohead had. In hindsight, this line of reasoning almost feels born from our widespread inability to take Coldplay on their own terms. They were never positioning themselves as being overly alternative, but they were strikingly adept at crafting emotive, immersive pop and rock songs that had just enough ingenuity to make them feel a touch more interesting than other mainstream ‘00s bands with whom they could be associated.

At the time, Viva La Vida definitely felt like Coldplay’s most unique album. Years later, that pretty much holds true; 2014's Ghost Stories was surprisingly downcast and restrained in diffuse meditations like "Midnight," but it did still have the EDM-bandwagon hit "A Sky Full Of Stars." In contrast, Viva La Vida fired off down all kinds of pathways, and all those detours yielded gorgeous discoveries.

Ten years later, it rests as the centerpiece of Coldplay’s catalog: preceded by three albums tracing their post-Britpop origins to true mainstream ascension, followed by three latter-day records as pop titans who had settled into an artistic identity people could either embrace or not. Viva La Vida was, in that sense, an odd waypoint. Adventurous in polite but effective ways, it is an objectively curious collection for a pop artist, and yet also laid the groundwork for Coldplay to depart from their roots entirely on subsequent albums.

Coldplay initially teased Viva La Vida with "Violet Hill." That was a very intentional opening salvo: What initially appears as if it could be another Coldplay piano ballad is quickly ruptured by small explosions of distorted guitar and a more emphatic beat than the band often utilized. It wasn’t radical, exactly, but it did signal that we were in for something else from Coldplay on Viva La Vida.

Eno pushed the band to delve into different sounds and approaches from song to song, and as a result Viva La Vida is one of Coldplay’s shortest and tightest albums yet also their most diverse. If "Violet Hill" had tipped us off, Viva La Vida's search for new horizons was confirmed as soon as you pressed play on the whole album and encountered "Life In Technicolor."

Coldplay have always had good opening tracks, songs that immediately open up the world of their respective albums. "Life In Technicolor" did the same, but was also primarily instrumental aside from a wordless refrain towards its end. Instead, the band let the song's primary riff -- played on a santoor, a hammered dulcimer type instrument used in Indian and Persian traditions -- dominate. (The song also bears the touch of one of the less-discussed contributors to Viva La Vida, electronic auteur Jon Hopkins, who would go on to work on Mylo Xyloto and Ghost Stories as well.)

There was something low-key shocking about Coldplay opening an album in this way; they had the good sense to let the song’s dreamscape sunrise exist as is, without forcing a single-ready melody on top of it. (They later released a vocal version called "Life In Techniclor ii" on Viva La Vida’s accompanying outtakes EP Prospekt’s March.) On the album, it was a perfect decision. The simple melody and steadily rising drama of "Life In Technicolor" is transportive.

It was an appropriate overture, as the rest of Viva La Vida called out to faraway lands in the process of creating its own little universe. What could've been another Coldplay piano rumination in "Lost!" instead leaned on organ and non-Western percussion for a more gratifying and memorable finished product. Hints of world music popped up elsewhere, too, in the Middle Eastern string figures of "Yes" or the Afropop guitars of "Strawberry Swing."

Looking outwards was a fitting musical endeavor for an album that sought to do the same thematically. It's curious to look back on the climate of 2008 from 2018. "Violet Hill," a song that features the line "Priests clutched onto Bibles/ Hollowed out to fit their rifles," was supposedly inspired by Fox News. This was the other big talking point ahead of Viva La Vida: It would be Coldplay’s political album, with French Revolution overtones and costumes, and narratives fixating on war and death and the redemption of love. As it goes with most of Coldplay’s work, this was the weaker aspect of Viva La Vida. The words were often just as oblique as usual; their gifts always lied in an impeccable sense of melody and arrangement more so than lyrical content.

Honestly, it didn’t really matter. Chris Martin occasionally had a way of delivering a line and making it sound stunning -- the motifs of "I’m gonna buy this place and burn it down" and "I'm gonna buy a gun and start a war" in "A Rush Of Blood To Head" come to mind. Viva La Vida had just as many clunkers as other Coldplay albums, but despite the inherent vagueness, their reach for the universal did mostly register. As twilit and idiosyncratic as many of these compositions were, they often sounded as if they were trying to bottle the whole planet up into three minutes, and they often succeeded.

Musically, Viva La Vida was overflowing with ideas. Some of the individual songs on Viva La Vida shift more restlessly than entire preceding Coldplay albums. On "42," Martin begins on piano, before the band kicks into an angular groove halfway through, before the whole thing brightens into an outro lacerated by a Strokes-ish guitar part, of all things. The ethereal lust of "Yes" subsides and is immediately answered by the ethereal rush of "Chinese Sleep Chant." (It’s hard to overstate how pleasantly mind-blowing it was to buy a Coldplay album in 2008 and realize they had hidden a goddamn shoegaze song in the middle of it.)

On paper, it still sounds like it should be a mess. But Coldplay came armed with hooks upon hooks for this thing, and the dual goals of honing their focus and pushing the borders of their sound yielded some of the most affecting songs of their career, like "Strawberry Swing." (Frank Ocean, who opened his breakthrough nostalgia, ULTRA mixtape with a barely altered "Strawberry Swing," was certainly affected.)

That song probably couldn’t have happened exactly that way on any other Coldplay album. A gently thrumming daydream, it’s a moment of peace on album of searching, a song that seems to emerge out of the air itself, humidity and tension becoming solid, then becoming a psychedelic prayer of sorts. "It’s such a perfect day," Martin sings, delivering a line he could’ve sang on God knows how many other Coldplay songs. But you never would’ve believed him as much as you did here.

"Strawberry Swing" was a highlight, but it was also indicative of Viva La Vida as a whole. Here, the band's gift for melody was corralled into a set of songs that each landed in their own way. Somehow, it all coheres. They’ve always been good at that, but Viva La Vida is an album that could’ve easily fallen apart in that regard. Instead, it’s achieved a rare feat: Each of these songs works great individually if you single them out and listen piecemeal, but the album is enveloping and rewarding when taken in as a whole.

Much of this could’ve been the recipe for a commercial downturn for Coldplay, the moment when mainstream radio listeners lost interest. That is, of course, assuming Coldplay were a more challenging band at their core. That is, of course, also ignoring the fact that Viva La Vida came with a title track destined for ubiquity. Built on percussive-then-swelling strings and somewhat nonsensical lyrics about empires, "Viva La Vida" might’ve seemed an unlikely candidate to become Coldplay's highest-charting single, but it actually remains their only #1 song in America. (Even that awful team-up with the Chainsmokers only peaked at #3.) It was in an iTunes commercial, but it was also just … everywhere.

Similarly, reading a description of Viva La Vida might lead you to believe that it was an unlikely candidate to become the best-selling album of 2008, and yet that is also true. This is the paradox of Viva La Vida. In making their "weird" left-turn album, Coldplay also continued their climb to a greater echelon of success. They had lots of hits before, songs like "Clocks" and "Yellow" and "The Scientist" that, regardless of their actual chart performance, embedded themselves in the atmosphere through years of syncs and less traceable ubiquity.

At the time, that made them singular amongst their one-time post-Britpop peers like Elbow or Doves; they were the band that scored big songs, that were just as well-known in America and everywhere else as in their native England. But Viva La Vida, while gesturing towards the potential of an artier Coldplay, was also when they departed from that early ‘00s context once and for all. From there, they entered a sphere of very famous and very successful pop acts. Their next album would feature a duet with Rihanna.

From here, Coldplay still had the chance to go in plenty directions. If they were wired differently, perhaps this would’ve been the harbinger of a retreat from pop concerns into more unpredictable creative waters. But this was also the moment where listeners had to decide whether we were going to accept Coldplay as they were. After this, the path was uneven, their clumsier pop moments mixed with further surprises. At the center, Viva La Vida is now the album all the rest of Coldplay’s career flows into and out of. The one where their various impulses and dispositions sat alongside each other, in tension but also feeding off one another, just like all the album’s disparate musical moods. And, for that one album, all of those competing elements were in perfect harmony.