Colin Stetson has probably frightened more listeners in the past week than in the preceding 15 years of his career. Many of them don't know his name.

Stetson, the idiosyncratic saxophonist known both for his intense solo albums and his involvement with acts including the Arcade Fire and Bon Iver, spent much of the last year-and-a-half devising the musical universe of Hereditary, the acclaimed new horror film that's so scary it's making viewers want to vomit or self-medicate with Xanax pills.

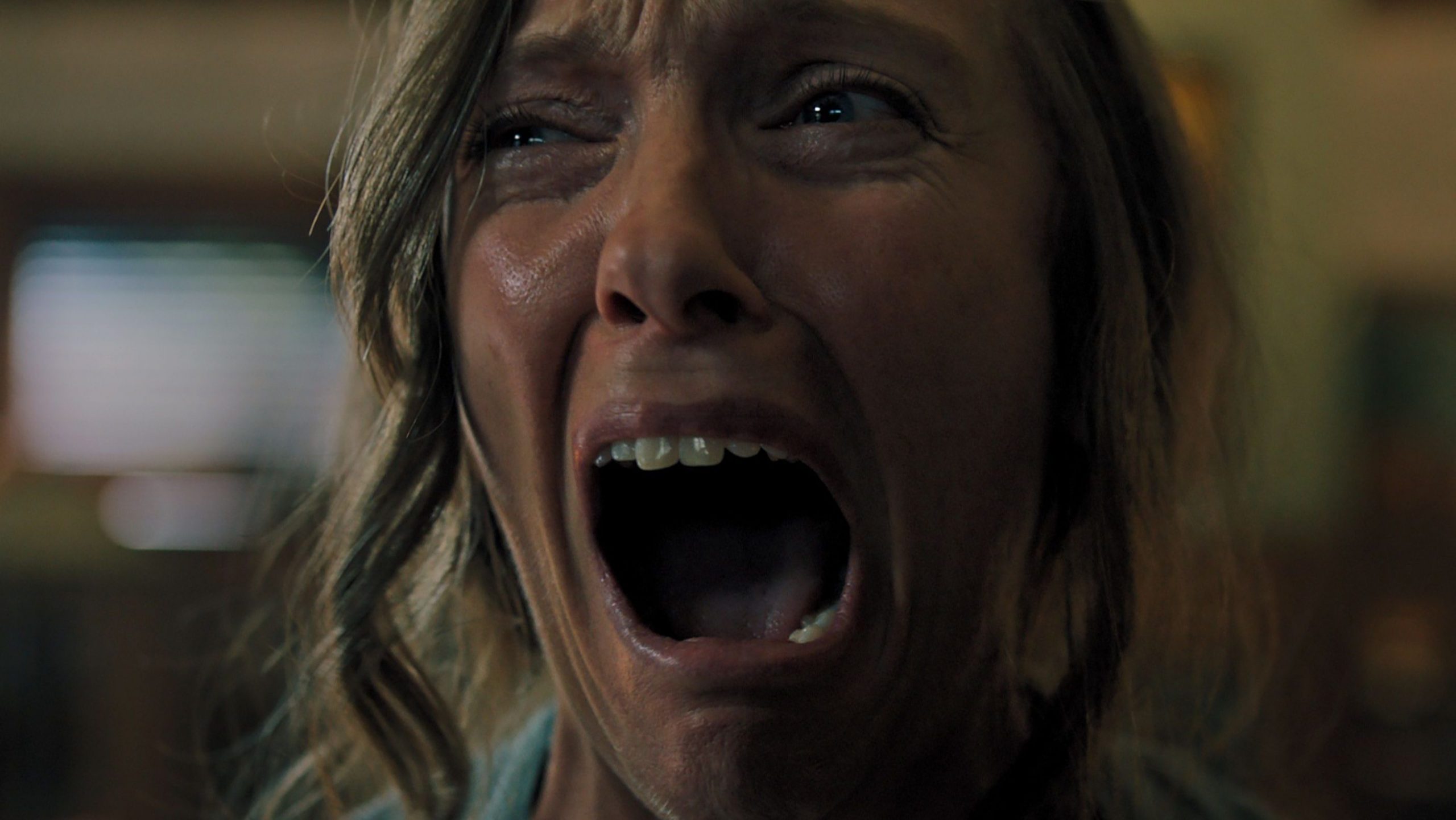

The film, if you haven't been peer-pressured into seeing it yet, is a truly unnerving depiction of a family whose quiet life in the woods turns into a domestic horror nightmare after the family's grandmother dies, buoyed by an immensely disturbing performance by Toni Collette. The atmosphere of slowly mounting terror owes a lot to Stetson's score, which functions as a sort of murmur of dread uncoiling constantly in the background as the unspeakable unfolds onscreen. Hereditary has drawn prominent comparisons with The Exorcist, and it's worth noting that music (both Jack Nitzsche original score and Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells) played a key role in that film's nightmarish appeal as well. (If you don't think you can stomach Hereditary but do want to hear the music, note that the soundtrack has been released on vinyl and major streaming platforms.)

Stetson says that he aimed to make the score sound "evil" and to avoid any conventional melodic elements whatsoever. He's clearly succeeded in those realms -- though the musician has amassed plenty of scoring experience (including the film Outlaws and Angels and the upcoming Hulu series The First), this is as grim and unsettling as his work gets.

Stetson (who is now halfway through recording his fifth solo album) spoke with us about how he conjured the fearsome sounds of Hereditary, as well as the liberating financial aspect of being able to supplement his touring income with scoring work.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

STEREOGUM: How did you become involved with Hereditary?

STETSON: Ari [Aster, the director] got in touch with me right after he finished the first draft of the script. He let me know he'd been using a lot of my solo music as inspiration, and that he was hoping to talk to me about scoring in the event that he gets the picture made. He sent me the script. By late 2016, things started to come together. I started scoring either in December of 2016 or January of 2017, just scoring off script and coming up with the major character of the score. It's really ideal that we had that time to establish the mood of the film music-wise, before the [filming] process got started.

STEREOGUM: How would you characterize the mood of the film? What emotions were you trying to evoke with this music?

STETSON: Early on, when Ari and I talked about what the score should do, he wanted it to feel "evil," quote-unquote. He wanted to avoid sentimentality and nostalgia; we were establishing the character of the events and the actions, which are already set in motion to affect and unravel the Graham family. I try not to think of it as writing conventional themes for particular characters in the storyline and more that the score itself was an unseen, additional cast member -- another character in the narrative. It would interact with each of the onscreen characters.

Early on, I realized that one of the main things the score would have to do is be tied intrinsically to picture to a degree that it never attracts attention to itself. I noticed that whenever something became too conventionally thematic or melodic, it really stuck out like a sore thumb. It attracted attention to itself and away from this gradually unfolding narrative. I wanted to avoid that.

STEREOGUM: Meaning you wanted to avoid any conventionally melodic themes?

STETSON: Yeah. I wanted to avoid attracting undue attention to the music itself, which I felt was a failure to the narrative. Another move I tried to make throughout was amplifying silence until the inherent sonic character became apparent. Just the idea of these musical spaces being amplifications of the dread and silence that was apparent in the picture. Blurring the lines between sound design and music became key. [I was] trying to avoid certain horror tropes and instrumentation usages that I feel are ubiquitous, and instead come up with ways to get those jobs done -- suspension and tension -- but not with the same instrumentation and timbres. When I see people write about the score, if they talk about instrumentation, nine times out of 10 it'll be entirely wrong.

STEREOGUM: Would you like to clarify what people are getting wrong about the instrumentation?

STETSON: People assume it's string-heavy. I can state pretty confidently that everything people think is a string is definitely not. The things that are strings are very few, and you wouldn't know it when you heard it [laughs].

STEREOGUM: What is the instrument that people are mistaking for strings?

STETSON: Most of the time it's clarinet. I did a lot of big clarinet choir ensembles for this. Clarinet and voice are probably the two most prominent instruments on the score. Both of them are obscured so as to not really be recognizable, at least to someone who's not really listening for it specifically. Beyond that, there's a pretty extensive use of brass. All the percussion in the film comes straight out of the amplified key percussion from all of my woodwind instruments. Something I use a lot in film scoring is contrabass clarinet, which can be used in so many different ways -- it can sound like synths, can sound like low strings, depending on how you play them and how you mic them. That was one of the first establishing aspects of the musical aesthetic. The idea was to mirror what's going on in the film and to hide in plain sight.

STEREOGUM: Do you regard the score as an extension of the evil spirits that take over the house in the film?

STETSON: Yeah. I avoid talking about it in those terms, because it's very easy to spoil this movie, so I dance around like a politician on a lot of stuff.

STEREOGUM: Right. I mean, people who haven't seen the movie know that bad shit is going to go down when they hear this score.

STETSON: Exactly.

STEREOGUM: How do you evoke such frightening emotions when you're making music? Do you have to do anything to put yourself in that zone?

STETSON: Just from talking to everyone I know who also works in film, sometimes you have a lot of work to do fixing other things -- fixing slow narrative, fixing dialogue -- where the score really needs to carry quite a bit beyond its fundamental charge. But with this, because Ari had crafted this really lean narrative -- the script is super tight, the acting is flawless -- it wasn't a chore to bring all the necessary emotions to play. All it took was some studying of what was happening there, zeroing in on the gradual build throughout the film. Finding inspiration was easy. Getting into the headspace wasn't a difficulty in this regard. The film does a good job of doing that. My process -- I'm kind of immersive in all things. I was pretty much out here working on this for the final stretch for the last three months. I play all the instruments in the scoring process. It's really just a one-man show over here. It's very easy to get caught up in the terror of it all when you're isolated and living with that story day in and day out.

STEREOGUM: You were immersing yourself in the more gruesome aspects of the script?

STETSON: Exactly. It was really just figuring out the pace of the thing, and the very, very minimalist quality of it aesthetically. Establishing which sound sources are going to best and most economically bring this to fruition. Also, a huge consideration was: Yes, this is a horror film, but it's a horror film couched in a really poignant family drama. It is not conventional; nor did I want the score to play out as such. I really was trying to establish something that didn't use familiar conventions. So it [would] create tension and mounting dread, but would do it in ways that felt like of a different world.

STEREOGUM: Are you a horror fan in general?

STETSON: No, I wouldn't say I'm particularly a fan of any one genre over another. I definitely wouldn't say I'm a horrorphile or anything.

STEREOGUM: Are there any horror soundtracks from older films that you were inspired by?

STETSON: My earliest scary movie memories are wrapped up in Poltergeist when I was a kid. I can still recall all of that score because it's so iconic. In terms of something that played more of an active role in teaching me how to craft something more minimalist and dread-establishing, Jóhann Jóhannsson's score for Prisoners is one of my two favorite film scores, and one I've drawn immense inspiration from over the years.

STEREOGUM: What's your other favorite film score?

STETSON: Hans Zimmer's score for The Thin Red Line, which is just perfection. And then probably I'd throw in Jonny Greenwood's score for There Will Be Blood.

STEREOGUM: The Hereditary score is being released on vinyl, right?

STETSON: Yeah! Milan Records is putting it out the same day the film comes out.

STEREOGUM: When would you recommend people listen to your score? Like, what activities or time of day would this be suited for?

STETSON: [laughs] I would never claim to know people's minds and when they like to juxtapose mood into their daily life. It's not that [the score] is not capable of being terrifying -- I just don't think that it is intrinsically that and nothing else. Because it's got a very methodical, very gradually unfolding quality to it, either first thing in the morning or last thing in the day. Those moments when you're shutting down at night and the last thing you're gonna do is settle in and give your last attention to it. Or waking up and day-establishing. That would be a fun experiment to see what happened to people if they did that -- what their day would be like.

STEREOGUM: If they started their day with the Hereditary score?

STETSON: Yeah! I tend to have very specific things that I start my day, musically speaking. That would be interesting.

STEREOGUM: You've been doing a lot of scoring work recently. How does doing music for film and TV make it easier to make a living as a working musician?

STETSON: It's certainly key if you want to stop having your main source of income be from the road. For me, over a decade of life was spent with the majority of time spent away from home. With the advent of streaming sites, that changed everything, now that people have been given every bit of music that's ever been produced for free. Now that content is essentially worthless, musicians have had to go a lot of different routes in order to not succumb to "Now you have to just stay on the road more than you already did to make the living you already were."

What you can see in aggregate across the industry is that more and more music gets written and produced specifically for these kinds of license-me niches. One of the main places you can make money is in licensing your music for film and TV. Another aspect of it is scoring. I didn't really fall into it through that, because the scoring thing was more a longtime desire for me. I really wanted to be working in film since I was a kid. When I was young, through my early years and through high school, I was a visual artist primarily and got much more serious about music at 15. When I went to university, I was a double major in art and music and always figured I would work in film in some visual aspect. That shifted, and then over the years, hearing these inspiring moments in soundtrack, I started to get much more inspired myself to do it. It's hard to just open that up yourself. You can put the word out there that you want to, but ultimately you need to be invited in on a project. When that started happening, I jumped on the opportunity. It just worked out for me that that longtime ambition also has allowed me to spend less time on the road.

STEREOGUM: Is it a relief for you that you don't need to rely on touring so much for income?

STETSON: Of course. Any touring musician who's not, like, 25 -- and probably many who are -- would tell you they'd appreciate more time to spend with friends and in their own bed.

STEREOGUM: What do you think makes Hereditary unique among other horror movies coming out?

STETSON: First and foremost, it's not a horror film -- obviously it is, but its core is this extremely heavy interpersonal drama. Starting from that place seemed like a bit of a novelty in the genre. It's very light on the jump scare and the familiar devices [of horror movies]. Like what I tried to do with the score, it's this wonderful slow burn that characterizes it outside of the pack of horror.

STEREOGUM: Do you believe in ghosts or evil spirits?

STETSON: No. I believe that people think that way. And that people believe in them. That belief is essentially identical to reality in the subjective experience. But do I believe in actual ghosts? No.